Bagpipes

Multi tool use

De doedelzakspeler ("Bagpipe Player"), Hendrick ter Brugghen, 1624 | |

| Woodwind instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification |

|

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 422.112 (Reed aerophone with conical bore) |

| Developed | 1000 BC by Hittites |

| Related instruments | |

| |

| Musicians | |

| |

Bagpipes are a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag. The Scottish Great Highland bagpipes are the best known in the Anglophone world; however, bagpipes have been played for a millennium or more throughout large parts of Europe, northern Africa, and western Asia, including Turkey, the Caucasus, and around the Persian Gulf. The term bagpipe is equally correct in the singular or plural, though pipers usually refer to the bagpipes as "the pipes", "a set of pipes" or "a stand of pipes".

Contents

1 Construction

1.1 Air supply

1.2 Bag

1.3 Chanter

1.3.1 Chanter reed

1.4 Drone

2 History

2.1 Ancient origins

2.2 Spread and development in Europe

2.3 Recent history

3 Modern usage

3.1 Types of bagpipes

3.1.1 Image gallery

3.2 Usage in non-traditional music

4 Publications

4.1 Periodicals

4.2 Books

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Construction

| ||||

A detail from the Cantigas de Santa Maria showing bagpipes with one chanter and a parallel drone (Spain, 13th century).

A detail from a painting by Hieronymus Bosch showing two bagpipers (15th century).

A Great Highland bagpipe practice chanter

A set of bagpipes minimally consists of an air supply, a bag, a chanter, and usually at least one drone. Many bagpipes have more than one drone (and, sometimes, more than one chanter) in various combinations, held in place in stocks—sockets that fasten the various pipes to the bag.

Air supply

The most common method of supplying air to the bag is through blowing into a blowpipe or blowstick. In some pipes the player must cover the tip of the blowpipe with their tongue while inhaling, but most blowpipes have a non-return valve that eliminates this need. In recent times, there are many instruments that assist in creating a clean air flow to the pipes and assist the collection of condensation.

An innovation, dating from the 16th or 17th century, is the use of a bellows to supply air. In these pipes, sometimes called "cauld wind pipes", air is not heated or moistened by the player's breathing, so bellows-driven bagpipes can use more refined or delicate reeds. Such pipes include the Irish uilleann pipes; the Scottish border or Lowland pipes; Northumbrian smallpipes, pastoral pipes and English Border pipes in Britain; and the musette de cour, cabrette and Musette bechonnet in France, the Dudy wielkopolskie, koziol bialy and koziol czarny in Poland.

Bag

The bag is an airtight reservoir that holds air and regulates its flow via arm pressure, allowing the player to maintain continuous even sound. The player keeps the bag inflated by blowing air into it through a blowpipe or pumping air into it with a bellows. Materials used for bags vary widely, but the most common are the skins of local animals such as goats, dogs, sheep, and cows. More recently, bags made of synthetic materials including Gore-Tex have become much more common. A drawback of the synthetic bag is the potential for fungal spores to colonise the bag because of a reduction in necessary cleaning, with the associated danger of lung infection.[1] An advantage of a synthetic bag is that it has a zip which allows the user to fit a more effective moisture trap to the inside of the bag.

Bags cut from larger materials are usually saddle-stitched with an extra strip folded over the seam and stitched (for skin bags) or glued (for synthetic bags) to reduce leaks. Holes are then cut to accommodate the stocks. In the case of bags made from largely intact animal skins, the stocks are typically tied into the points where limbs and the head joined the body of the whole animal, a construction technique common in Central Europe.

Chanter

The chanter is the melody pipe, played with two hands. Almost all bagpipes have at least one chanter; some pipes have two chanters, particularly those in North Africa, the Balkans in Southern Europe, and Southwest Asia. A chanter can be bored internally so that the inside walls are parallel (or "cylindrical") for its full length, or it can be bored in a conical shape.

The chanter is usually open-ended, so there is no easy way for the player to stop the pipe from sounding. Thus most bagpipes share a constant, legato sound where there are no rests in the music. Primarily because of this inability to stop playing, technical movements are used to break up notes and to create the illusion of articulation and accents. Because of their importance, these embellishments (or "ornaments") are often highly technical systems specific to each bagpipe, and take many years of study to master. A few bagpipes (such as the musette de cour, the uilleann pipes, the Northumbrian smallpipe, the piva and the left chanter of the surdulina) have closed ends or stop the end on the player's leg, so that when the player "closes" (covers all the holes) the chanter becomes silent.

A practice chanter is a chanter without bag or drones, allowing a player to practice the instrument quietly and with no variables other than playing the chanter.

The term chanter is derived from the Latin cantare, or "to sing", much like the modern French word chanteur.

Chanter reed

The note from the chanter is produced by a reed installed at its top. The reed may be a single (a reed with one vibrating tongue) or double reed (of two pieces that vibrate against each other). Double reeds are used with both conical- and parallel-bored chanters while single reeds are generally (although not exclusively) limited to parallel-bored chanters. In general, double-reed chanters are found in pipes of Western Europe while single-reed chanters appear in most other regions.

Drone

Play media

Play mediaBagpipes players from The City Of Auckland Pipe Band.

Most bagpipes have at least one drone: a pipe which is generally not fingered but rather produces a constant harmonizing note throughout play (usually the tonic note of the chanter). Exceptions are generally those pipes which have a double-chanter instead. A drone is most commonly a cylindrically-bored tube with a single reed, although drones with double reeds exist. The drone is generally designed in two or more parts with a sliding joint so that the pitch of the drone can be adjusted.

Depending on the type of pipes, the drones may lie over the shoulder, across the arm opposite the bag, or may run parallel to the chanter. Some drones have a tuning screw, which effectively alters the length of the drone by opening a hole, allowing the drone to be tuned to two or more distinct pitches. The tuning screw may also shut off the drone altogether. In most types of pipes, where there is one drone it is pitched two octaves below the tonic of the chanter. Additional drones often add the octave below and then a drone consonant with the fifth of the chanter.

History

Ancient origins

The evidence for pre-Roman era bagpipes is still uncertain but several textual and visual clues have been suggested. The Oxford History of Music says that a sculpture of bagpipes has been found on a Hittite slab at Euyuk in the Middle East, dated to 1000 BC. Several authors identify the ancient Greek askaulos (ἀσκός askos – wine-skin, αὐλός aulos – reed pipe) with the bagpipe.[2] In the 2nd century AD, Suetonius described the Roman emperor Nero as a player of the tibia utricularis.[3]Dio Chrysostom wrote in the 1st century of a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe (tibia, Roman reedpipes similar to Greek and Etruscan instruments) with his mouth as well as by tucking a bladder beneath his armpit.[4]

Spread and development in Europe

Medieval bagpiper at the Cistercian monastery of Santes Creus, Catalonia, Spain

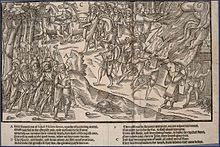

Image of Irelande, Military use of the bagpipe dated 1581

In the early part of the second millennium, definite clear attestations of bagpipes began to appear with frequency in Western European art and iconography. The Cantigas de Santa Maria, written in Galician-Portuguese and compiled in Castile in the mid-13th century, depicts several types of bagpipes.[5] Several illustrations of bagpipes also appear in the Chronique dite de Baudoin d’Avesnes, a 13th-century manuscript of northern French origin.[6][7] Although evidence of bagpipes in the British Isles prior to the 14th century is contested, they are explicitly mentioned in The Canterbury Tales (written around 1380):[8]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

A baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne, /And ther-with-al he broghte us out of towne.

— Canterbury Tales

Bagpipes were also frequent subjects for carvers of wooden choir stalls in the late 15th and early 16th century throughout Europe, sometimes with animal musicians.[9]

Actual examples of bagpipes from before the 18th century are extremely rare; however, a substantial number of paintings, carvings, engravings, manuscript illuminations, and so on survive. They make it clear that bagpipes varied hugely throughout Europe, and even within individual regions. Many examples of early folk bagpipes in continental Europe can be found in the paintings of Brueghel, Teniers, Jordaens, and Durer.[10]

A bagpiper busking with the Great Highland bagpipe on the street in Edinburgh, Scotland

The first clear reference to the use of the Scottish Highland bagpipes is from a French history, which mentions their use at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh in 1547. George Buchanan (1506–82) claimed that they had replaced the trumpet on the battlefield. This period saw the creation of the ceòl mór (great music) of the bagpipe, which reflected its martial origins, with battle-tunes, marches, gatherings, salutes and laments.[11] The Highlands of the early seventeenth century saw the development of piping families including the MacCrimmonds, MacArthurs, MacGregors and the Mackays of Gairloch.[12]

Evidence of the bagpipe in Ireland occurs in 1581, when John Derrick's The Image of Irelande clearly depicts a bagpiper. Derrick's illustrations are considered to be reasonably faithful depictions of the attire and equipment of the English and Irish population of the 16th century.[13] The "Battell" sequence from My Ladye Nevells Booke (1591) by William Byrd, which probably alludes to the Irish wars of 1578, contains a piece entitled The bagpipe: & the drone. In 1760, the first serious study of the Scottish Highland bagpipe and its music was attempted, in Joseph MacDonald's Compleat Theory. Further south, a manuscript from the 1730s by a William Dixon from Northumberland contains music that fits the border pipes, a nine-note bellows-blown bagpipe whose chanter is similar to that of the modern Great Highland bagpipe. However the music in Dixon's manuscript varied greatly from modern Highland bagpipe tunes, consisting mostly of extended variation sets of common dance tunes. Some of the tunes in the Dixon manuscript correspond to tunes found in early 19th century published and manuscript sources of Northumbrian smallpipe tunes, notably the rare book of 50 tunes, many with variations, by John Peacock.

Happy Brothers by Uroš Predić (1887)

As Western classical music developed, both in terms of musical sophistication and instrumental technology, bagpipes in many regions fell out of favour due to their limited range and function. This triggered a long, slow decline that continued, in most cases, into the 20th century.

Extensive and documented collections of traditional bagpipes can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the International Bagpipe Museum in Gijón, Spain, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, England and the Morpeth Chantry Bagpipe Museum in Northumberland, and the Musical Instrument Museum in Phoenix, Arizona.

Recent history

A Canadian soldier plays the bagpipes during the War in Afghanistan. Bagpipes are frequently used during funerals and memorials, especially among fire department, military and police forces in the United Kingdom, Ireland, the Commonwealth realms, and the US.

During the expansion of the British Empire, spearheaded by British military forces that included Highland regiments, the Scottish Great Highland bagpipe became well-known worldwide. This surge in popularity was boosted by large numbers of pipers trained for military service in World War I and World War II. The surge coincided with a decline in the popularity of many traditional forms of bagpipe throughout Europe, which began to be displaced by instruments from the classical tradition and later by gramophone and radio.

In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth Nations such as Canada, New Zealand and Australia the Great Highland bagpipe is commonly used in the military and is often played in formal ceremonies. Foreign militaries patterned after the British Army have also taken the Highland bagpipe into use including Uganda, Sudan, India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Jordan, and Oman. Many police and fire services in Scotland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and the United States have also adopted the tradition of fielding pipe bands.

A bagad in Brest, France

In recent years, often driven by revivals of native folk music and dance, many types of bagpipes have enjoyed a resurgence in popularity and, in many cases, instruments that were on the brink of obscurity have become extremely popular. In Brittany, the Great Highland bagpipe and concept of the pipe band were appropriated to create a Breton interpretation, the bagad. The pipe band idiom has also been adopted and applied to the Galician gaita as well. Additionally, bagpipes have often been used in various films depicting moments from Scottish and Irish history; the film Braveheart and the theatrical show Riverdance have served to make the uilleann pipes more commonly known.

Bagpipes are sometimes played at formal events in Commonwealth universities, particularly in Canada. Because of the Scottish influences on the sport of curling, bagpipes are also the official instrument of the World Curling Federation and are commonly played during a ceremonial procession of teams before major curling championships.

Bagpipe making was once a craft that produced instruments in many distinctive local traditional styles. Today, the world's biggest producer of the instrument is Pakistan, where the industry was worth $6.8 million in 2010.[14][15] In the late 20th century, various models of electronic bagpipes were invented. The first custom-built MIDI bagpipes were developed by the Asturian piper known as Hevia (José Ángel Hevia Velasco).[16]

Modern usage

Types of bagpipes

Dozens of types of bagpipes today are widely spread across Europe and the Middle East, as well as through much of the former British Empire. The name bagpipe has almost become synonymous with its best-known form, the Great Highland bagpipe, overshadowing the great number and variety of traditional forms of bagpipe. Despite the decline of these other types of pipes over the last few centuries, in recent years many of these pipes have seen a resurgence or revival as musicians have sought them out; for example, the Irish piping tradition, which by the mid 20th century had declined to a handful of master players is today alive, well, and flourishing a situation similar to that of the Asturian gaita, the Galician gaita, the Portuguese gaita transmontana, the Aragonese gaita de boto, Northumbrian smallpipes, the Breton biniou, the Balkan gaida, the Romanian cimpoi, the Black Sea tulum, the Scottish smallpipes and pastoral pipes, as well as other varieties.

Traditionally, one of the purposes of the bagpipe was to provide music for dancing. This has declined with the growth of dance bands, recordings, and the decline of traditional dance. In turn, this has led to many types of pipes developing a performance-led tradition, and indeed much modern music based on the dance music tradition played on bagpipes is no longer suitable for use as dance music.

Image gallery

Bulgarian Kaba gaida player

The Scottish Great Highland bagpipe played at a Canadian military function

A musician with a Northern Italian Baghèt wearing traditional dress.

Modern baghet (made 2000 by Valter Biella) in Sol/G

Central and southern Italian zampogna

Laz man from Turkey playing a tulum

Cillian Vallely playing Irish Uilleann pipes

Northumbrian smallpipes

Man from Skopje, Macedonia playing the Gaida

Galician gaita

Sruti upanga, a Southern Indian bagpipe

Hungarian duda

Serbian piper

Polish pipers

Bagad of Lann Bihoué from the French Navy

Swedish säckpipa

Pastoral pipes with removable footjoint and bellows

Street piper from Sofia, Bulgaria

Estonian piper

Lithuanian piper

Modern German huemmelchen

Lithuanian bagpipes

Asturian gaita

Welsh bagpipe (double-reed type)

Cantabrian pipe band

Syrian piper in Damascus, Syria

Various forms of the Tsampouna, found in the Greek islands

Belarusian piper

Maltese Żaqq

Man playing the bagpipe on Dam square. background: Royal Palace of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Romanian cimpoi player

Play media

Play media

Ľubomír Párička playing bagpipes, Slovak Republic

Usage in non-traditional music

Celtic rock band Enter the Haggis featuring Highland bagpipes

Since the 1960s, bagpipes have also made appearances in other forms of music, including rock, metal, jazz, hip-hop, punk, and classical music, for example with Paul McCartney's "Mull of Kintyre", AC/DC's "It's a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock 'n' Roll)", and Peter Maxwell Davies's composition An Orkney Wedding, with Sunrise.

Publications

Periodicals

Periodicals covering specific types of bagpipes are addressed in the article for that bagpipe

An Píobaire, Dublin: Na Píobairí Uilleann.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}.

Chanter, The Bagpipe Society.

The Piping Times, Glasgow: The College of Piping.

Piping Today, Glasgow: The National Piping Centre.

Utriculus, Italy: Circolo della Zampogna.

The Voice, Newark, DL: The Eastern United States Pipe Band Association.

Books

Baines, Anthony (Nov 1991), Woodwind Instruments and Their History, Dover Pub, ISBN 0-486-26885-3.

——— (1995), Bagpipes (3rd ed.), Pitt Rivers Museum, Univ. of Oxford, ISBN 0-902793-10-1, 147 pp. with plates.

Cheape, Hugh, The Book of the Bagpipe.

Collinson, Francis (1975), The Bagpipe, The History of a Musical Instrument.

See also

- List of bagpipes

- List of bagpipers

- List of pipe makers

- List of pipe bands

- List of published bagpipe music

- List of nontraditional bagpipe usage

- List of bagpipe technology books

- List of composers who employed pipe music

- Glossary of bagpipe terms

- Practice chanter

References

^ "Bagpipe warning over threat of fatal fungus – Health". The Scotsman. 2013-03-10. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

^ William Flood. "The Story of the Bagpipe" p. 15

^ "Life of Nero, 54", Suetonius, The Lives of the Caesars, Loeb Classical Library, p. 185, retrieved 2013-01-02

^ "Discourses by Dio Chrysostom (Or. 71.9)", The Seventy-first Discourse: On the Philosopher (Volume V), Loeb Classical Library, V, p. 173, retrieved 2013-01-02

^ Aubrey, Elizabeth (1996), The Music of the Troubadours, Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-21389-1, retrieved 2013-01-02

^ Chronique dite de Baudoin d'Avesnes, Arras, BM, ms. 0863, f. 007, 126v, 149v

^ "Hybride jouant de la cornemuse". Sorbonne, Paris.

^ Chaucer, Geoffrey, The Canterbury Tales: Prologue to "The Miller's Tale" (line 565), retrieved 2013-01-02

^ "Cochon jouant de la cornemuse". Sorbonne, Paris.

^ The Great Highland Bagpipes (an piob-mhor), The Northport Pipe Band, NY, archived from the original on February 11, 2013, retrieved 2013-01-02

^ J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007),

ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, p. 169.

^ J. Porter, "Introduction" in J. Porter, ed., Defining Strains: The Musical Life of Scots in the Seventeenth Century (Peter Lang, 2007),

ISBN 3-03910-948-0, p. 35.

^ Derrick, John (1581), The Image of Irelande, London

^ Jaine, Caroline (2011-10-04), Doing business with Pakistan, Dawn, retrieved 2013-02-02

^ Abbas, Nosheen (2012-12-31). "The thriving bagpipe business of Pakistan". Pakistan: BBC News Online. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

^ Roza-Vigil, Susana (1999-11-05), Bagpipes resonate through rugged coastline of... Spain, WorldBeat, Spain: CNN, retrieved 2013-01-02

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bagpipes. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bag-pipe. |

- Bagpipe iconography – Paintings and images of the pipes.

- A demonstration of rare instruments including bagpipes

The Concise History of the Bagpipe by Frank J. Timoney

The Bagpipe Society, dedicated to promoting the study, playing, and making of bagpipes and pipes from around the world- Bagpipes from polish collections (Polish folk musical instruments)

Bagpipes (local polish name "Koza") played by Jan Karpiel-Bułecka (English subtitles)- Official site of Baghet (bagpipe from North Italy) players.

- Celtic Music : Scottish Military Bagpipes.

OWLg,RZu88