Allyl group

Structure of the allyl group

An allyl group is a substituent with the structural formula H2C=CH−CH2R, where R is the rest of the molecule. It consists of a methylene bridge (−CH2−) attached to a vinyl group (−CH=CH2).[1][2] The name is derived from the Latin word for garlic, Allium sativum. In 1844, Theodor Wertheim isolated an allyl derivative from garlic oil and named it "Schwefelallyl".[3][4] The term allyl applies to many compounds related to H2C=CH−CH2, some of which are of practical or of everyday importance, for example, allyl chloride.

Contents

1 Nomenclature

1.1 Pentadienyl

1.1.1 Homoallylic

2 Bonding

3 Allylation

3.1 Carbonyl allylation

4 Allyl compounds

5 See also

6 References

Nomenclature

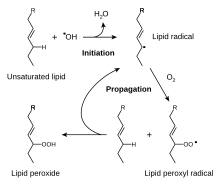

The free radical pathway for the first phase of the oxidative rancidification of fats

A site next to the unsaturated carbon atom is called the allylic position or allylic site. A group attached at this site is sometimes described as allylic. Thus, CH2=CHCH2OH "has an allylic hydroxyl group". Allylic C−H bonds are about 15% weaker than the C−H bonds in ordinary sp3 carbon centers and are thus more reactive. This heightened reactivity has many practical consequences. The industrial production of acrylonitrile by ammoxidation of propene exploits the easy oxidation of the allylic C−H centers:

- 2CH3−CH=CH2 + 2NH3 + 3O2 → 2CH2=CH−C≡N + 6H2O

Unsaturated fats spoil by rancidification involving attack at allylic C−H centers.

Benzylic and allylic are related in terms of structure, bond strength, and reactivity. Other reactions that tend to occur with allylic compounds are allylic oxidations, ene reactions, and the Tsuji–Trost reaction. Benzylic groups are related to allyl groups; both show enhanced reactivity.

Pentadienyl

A CH2 group connected to two vinyl groups is said to be doubly allylic. The bond dissociation energy of C−H bonds on a doubly allylic centre is about 10% less than the bond dissociation energy of a C−H bond that is allylic. The weakened C−H bonds reflect the high stability of the resulting pentadienyl radicals. Compounds containing the C=C−CH2−C=C linkages, e.g. linoleic acid derivatives, are prone to autoxidation, which can lead to polymerization or form semisolids. This reactivity pattern is fundamental to the film-forming behavior of the "drying oils", which are components of oil paints and varnishes.

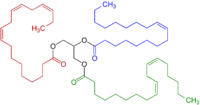

A representative triglyceride found in linseed oil features groups with both singly and doubly allylic CH2 sites (linoleic acid and alpha-linolenic acid) and singly allylic sites (oleic acid)

Homoallylic

The term homoallylic refers to the position on a carbon skeleton next to an allylic position. In but-3-enyl chloride CH2=CHCH2CH2Cl, the chloride occupies a homoallylic position.

The allylic, homoallylic and doubly allylic sites are highlighted in red

Bonding

The allyl group is widely encountered in organic chemistry.[1] Allylic radicals, anions, and cations are often discussed as intermediates in reactions. All feature three contiguous sp²-hybridized carbon centers and all derive stability from resonance.[5] Each species can be presented by two resonance structures with the charge or unpaired electron distributed at both 1,3 positions.

Resonance structure of the allyl anion

In terms of MO theory, the MO diagram has three molecular orbitals: the first one bonding, the second one non-bonding and the higher energy orbital is antibonding.[2]

MO diagram for π orbitals on the allyl radical. The middle MO labeled Ψ2 is singly occupied in the allyl radical. In the allyl cation Ψ2 is unoccupied and in the allyl anion it is doubly occupied. Hydrogen atoms are omitted from this picture.

Allylation

Allylation is any chemical reaction that adds an allyl group to a substrate.[1]

Carbonyl allylation

Typically allylation refers to the addition of an allyl anion equivalent to an organic electrophile:[6][7]Carbonyl allylation is a type of organic reaction in which an activated allyl group is added to carbonyl group producing an allylic tertiary alcohol. A typical allylation of an aldehyde (RCHO) is represented by the following two-step process that begins with allylation followed by hydrolysis of the intermediate:

- RCHO + CH2=CHCH2M → CH2=CHCH2RCH(OM)

- CH2=CHCH2RCH(OM) + H2O → CH2=CHCH2RCH(OH) + MOH

A popular reagent for asymmetric allylation is the "Brown reagent", allyldiisopinocampheylborane.[8]

The introduction of allylic groups into molecular frameworks generates many opportunities for downstream diversification. A common method to introduce allyl moieties into organic molecules is through 1,2-allylation of carbonyl groups. The homoallylic alcohol products can undergo a variety of diversity-generating reactions such as ozonolysis, epoxidation, and olefin metathesis. Allylmetal reagents such as allylboranes, allylstannanes, and allylindium compounds are commonly used by organic chemists to introduce allyl groups.[9]

Aldehyde allylation strategy en route to antascomycin B

Allylstannanes are relatively stable reagents in the allylmetal family, and have been employed in a variety of complex organic syntheses. In fact, allylstannane addition is one of the most common methods for producing polypropionates, polyacetates, and other oxygenated molecules with a contiguous arrays of stereocenters.[10] Ley and coworkers[11] used an allylstannane to allylate a threose-derived aldehyde (see figure) en route to the macrolide antascomicin B, which structurally resembles FK506 and rapamycin, and is a potent binder of FKBP12.

Allylboration is also often used to add allyl groups in a 1,2 fashion to aldehydes and ketones. Thanks to decades of research, there is now a wide variety of organoboron reagents available to the synthetic chemist, including organoboranes that predictably yield products in high diastereo- and enantioselectivity.[12] If a one-pot metal insertion and allylation procedure is required, indium- mediated allylation is an attractive option for generating homoallylic alcohols directly from allyl halides and carbonyl compounds. In general, the method is called the Barbier reaction, and can employ a variety of metals such as magnesium, aluminium, zinc, indium, and tin. The reaction is often used as a milder form of the Grignard addition reaction, and can often tolerate aqueous solvents[13]

Allyl compounds

Many substituents can be attached to the allyl group to give stable compounds. Commercially important allyl compounds include:

Allyl alcohol (H2C=CH−CH2OH)

Allyl chloride (H2C=CH−CH2Cl)

Crotyl alcohol (CH3CH=CH−CH2OH)

Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, central in the biosynthesis of terpenes, a precursor to many natural products, including natural rubber.

Transition-metal allyl complexes, such as allylpalladium chloride dimer

See also

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Allyl group |

- Allylic strain

- Carroll rearrangement

- Allylic palladium complex

- Tsuji–Trost reaction

References

^ abc Jerry March, "Advanced Organic Chemistry" 4th Ed. J. Wiley and Sons, 1992: New York. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-471-60180-2.

^ ab Organic Chemistry 4th Ed. Morisson & Boyd 1988.

^ Theodor Wertheim (1844). "Untersuchung des Knoblauchöls". Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie. 51 (3): 289. doi:10.1002/jlac.18440510302.

^ Eric Block (2010). Garlic and Other Alliums: The Lore and the Science. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0-85404-190-7.

^ Organic Chemistry John McMurry 2nd ed. 1988

^ http://www.chem.umn.edu/groups/harned/classes/8322/lectures/2AllylationReactions.pdf

^ S. E. Denmark, J. Fu "Catalytic Enantioselective Addition of Allylic Organometallic Reagents to Aldehydes and Ketones" Chem. Rev., 2003, vol. 103, pp 2763–2794. doi:10.1021/cr020050h

^ Y. Yamamoto, N. Asao "Selective reactions using allylic metals" Chem. Rev., 1993, vol. 93, pp 2207–2293. doi:10.1021/cr00022a010

^ Yus, M; Gonzalez-Gomez, J. C.; Foubelo, F. Chem. Rev., 2013, 113, 5595–5698

^ Keck, G. E.; Dougherty, S. M.; Savin, K. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 6210

^ Brittain, D. E. A.; Griffiths-Jones, C. M.; Linder, M. R.; Smith, M. D.; McCusker, C.; Barlow, J. S.; Akiyama, R.; Yasuda, K.; Ley, S. V. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2732.

^ Yus, M; Gonzalez-Gomez, J. C.; Foubelo, F. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7774–7854.

^ Shen, Z.; Wang, S.; Chok, Y.; Xu, Y.; Loh, T. Chem. Rev., 2013, 113, 271–401.