Kepler's laws of planetary motion

In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion are three scientific laws describing the motion of planets around the Sun.

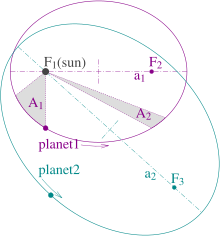

Figure 1: Illustration of Kepler's three laws with two planetary orbits.

- The orbits are ellipses, with focal points F1 and F2 for the first planet and F1 and F3 for the second planet. The Sun is placed in focal point F1.

- The two shaded sectors A1 and A2 have the same surface area and the time for planet 1 to cover segment A1 is equal to the time to cover segment A2.

- The total orbit times for planet 1 and planet 2 have a ratio (a1a2)32{textstyle left({frac {a_{1}}{a_{2}}}right)^{frac {3}{2}}}

.

| Astrodynamics |

|---|

|

Orbital mechanics |

Equations

|

Efficiency measures

|

- The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

- A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.[1]

- The square of the orbital period of a planet is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

Most planetary orbits are nearly circular, and careful observation and calculation are required in order to establish that they are not perfectly circular. Calculations of the orbit of Mars, whose published values are somewhat suspect,[2] indicated an elliptical orbit. From this, Johannes Kepler inferred that other bodies in the Solar System, including those farther away from the Sun, also have elliptical orbits.

Kepler's work (published between 1609 and 1619) improved the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, explaining how the planets' speeds varied, and using elliptical orbits rather than circular orbits with epicycles.[3]

Isaac Newton showed in 1687 that relationships like Kepler's would apply in the Solar System to a good approximation, as a consequence of his own laws of motion and law of universal gravitation.

Contents

1 Comparison to Copernicus

2 Nomenclature

3 History

4 Formulary

4.1 First law of Kepler

4.2 Second law of Kepler

4.3 Third law of Kepler

5 Planetary acceleration

5.1 Acceleration vector

5.2 Inverse square law

5.3 Newton's law of gravitation

6 Position as a function of time

6.1 Mean anomaly, M

6.2 Eccentric anomaly, E

6.3 True anomaly, θ

6.4 Distance, r

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 Bibliography

11 External links

Comparison to Copernicus

Kepler's laws improved the model of Copernicus. If the eccentricities of the planetary orbits are taken as zero, then Kepler basically agreed with Copernicus:

- The planetary orbit is a circle

- The Sun is at the center of the orbit

- The speed of the planet in the orbit is constant

The eccentricities of the orbits of those planets known to Copernicus and Kepler are small, so the foregoing rules give fair approximations of planetary motion, but Kepler's laws fit the observations better than does the model proposed by Copernicus.

Kepler's corrections are not at all obvious:

- The planetary orbit is not a circle, but an ellipse.

- The Sun is not at the center but at a focal point of the elliptical orbit.

- Neither the linear speed nor the angular speed of the planet in the orbit is constant, but the area speed is constant.

The eccentricity of the orbit of the Earth makes the time from the March equinox to the September equinox, around 186 days, unequal to the time from the September equinox to the March equinox, around 179 days. A diameter would cut the orbit into equal parts, but the plane through the Sun parallel to the equator of the Earth cuts the orbit into two parts with areas in a 186 to 179 ratio, so the eccentricity of the orbit of the Earth is approximately

- e≈π4186−179186+179≈0.015,{displaystyle eapprox {frac {pi }{4}}{frac {186-179}{186+179}}approx 0.015,}

which is close to the correct value (0.016710219) (see Earth's orbit).

The calculation is correct when perihelion, the date the Earth is closest to the Sun, falls on a solstice. The current perihelion, near January 3, is fairly close to the solstice of December 21 or 22.

Nomenclature

It took nearly two centuries for the current formulation of Kepler's work to take on its settled form. Voltaire's Eléments de la philosophie de Newton (Elements of Newton's Philosophy) of 1738 was the first publication to use the terminology of "laws".[4][5] The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers in its article on Kepler (p. 620) states that the terminology of scientific laws for these discoveries was current at least from the time of Joseph de Lalande.[6] It was the exposition of Robert Small, in An account of the astronomical discoveries of Kepler (1814) that made up the set of three laws, by adding in the third.[7] Small also claimed, against the history, that these were empirical laws, based on inductive reasoning.[5][8]

Further, the current usage of "Kepler's Second Law" is something of a misnomer. Kepler had two versions, related in a qualitative sense: the "distance law" and the "area law". The "area law" is what became the Second Law in the set of three; but Kepler did himself not privilege it in that way.[9]

History

Johannes Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe.[10][3][11] Kepler's third law was published in 1619.[12][3] Kepler had believed in the Copernican model of the solar system, which called for circular orbits, but he could not reconcile Brahe's highly precise observations with a circular fit to Mars' orbit—Mars coincidentally having the highest eccentricity of all planets except Mercury.[13] His first law reflected this discovery.

Kepler in 1621 and Godefroy Wendelin in 1643 noted that Kepler's third law applies to the four brightest moons of Jupiter.[Nb 1] The second law, in the "area law" form, was contested by Nicolaus Mercator in a book from 1664, but by 1670 his Philosophical Transactions were in its favour. As the century proceeded it became more widely accepted.[14] The reception in Germany changed noticeably between 1688, the year in which Newton's Principia was published and was taken to be basically Copernican, and 1690, by which time work of Gottfried Leibniz on Kepler had been published.[15]

Newton was credited with understanding that the second law is not special to the inverse square law of gravitation, being a consequence just of the radial nature of that law; while the other laws do depend on the inverse square form of the attraction. Carl Runge and Wilhelm Lenz much later identified a symmetry principle in the phase space of planetary motion (the orthogonal group O(4) acting) which accounts for the first and third laws in the case of Newtonian gravitation, as conservation of angular momentum does via rotational symmetry for the second law.[16]

Formulary

The mathematical model of the kinematics of a planet subject to the laws allows a large range of further calculations.

First law of Kepler

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.

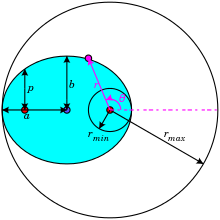

Figure 2: Kepler's first law placing the Sun at the focus of an elliptical orbit

Figure 4: Heliocentric coordinate system (r, θ) for ellipse. Also shown are: semi-major axis a, semi-minor axis b and semi-latus rectum p; center of ellipse and its two foci marked by large dots. For θ = 0°, r = rmin and for θ = 180°, r = rmax.

Mathematically, an ellipse can be represented by the formula:

- r=p1+εcosθ,{displaystyle r={frac {p}{1+varepsilon ,cos theta }},}

where p{displaystyle p}

For an ellipse 0 < ε < 1 ; in the limiting case ε = 0, the orbit is a circle with the sun at the centre (i.e. where there is zero eccentricity).

At θ = 0°, perihelion, the distance is minimum

- rmin=p1+ε{displaystyle r_{min }={frac {p}{1+varepsilon }}}

At θ = 90° and at θ = 270° the distance is equal to p{displaystyle p}

At θ = 180°, aphelion, the distance is maximum (by definition, aphelion is – invariably – perihelion plus 180°)

- rmax=p1−ε{displaystyle r_{max }={frac {p}{1-varepsilon }}}

The semi-major axis a is the arithmetic mean between rmin and rmax:

- rmax−a=a−rmina=p1−ε2{displaystyle {begin{aligned}r_{max }-a&=a-r_{min }\[3pt]a&={frac {p}{1-varepsilon ^{2}}}end{aligned}}}

The semi-minor axis b is the geometric mean between rmin and rmax:

- rmaxb=brminb=p1−ε2{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {r_{max }}{b}}&={frac {b}{r_{min }}}\[3pt]b&={frac {p}{sqrt {1-varepsilon ^{2}}}}end{aligned}}}

The semi-latus rectum p is the harmonic mean between rmin and rmax:

- 1rmin−1p=1p−1rmaxpa=rmaxrmin=b2{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {1}{r_{min }}}-{frac {1}{p}}&={frac {1}{p}}-{frac {1}{r_{max }}}\[3pt]pa&=r_{max }r_{min }=b^{2},end{aligned}}}

The eccentricity ε is the coefficient of variation between rmin and rmax:

- ε=rmax−rminrmax+rmin.{displaystyle varepsilon ={frac {r_{max }-r_{min }}{r_{max }+r_{min }}}.}

The area of the ellipse is

- A=πab.{displaystyle A=pi ab,.}

The special case of a circle is ε = 0, resulting in r = p = rmin = rmax = a = b and A = πr2.

Second law of Kepler

A line joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.[1]

The same (blue) area is swept out in a fixed time period. The green arrow is velocity. The purple arrow directed towards the Sun is the acceleration. The other two purple arrows are acceleration components parallel and perpendicular to the velocity.

The orbital radius and angular velocity of the planet in the elliptical orbit will vary. This is shown in the animation: the planet travels faster when closer to the sun, then slower when farther from the sun. Kepler's second law states that the blue sector has constant area.

In a small time dt{displaystyle dt,}

The area enclosed by the elliptical orbit is πab.{displaystyle pi ab.,}

- P⋅12r2dθdt=πab{displaystyle Pcdot {frac {1}{2}}r^{2}{frac {dtheta }{dt}}=pi ab}

and the mean motion of the planet around the Sun

- n=2πP{displaystyle n={frac {2pi }{P}}}

satisfies

- r2dθ=abndt.{displaystyle r^{2},dtheta =abn,dt.}

Third law of Kepler

The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

This captures the relationship between the distance of planets from the Sun, and their orbital periods.

Kepler enunciated in 1619[12] this third law in a laborious attempt to determine what he viewed as the "music of the spheres" according to precise laws, and express it in terms of musical notation.[17]

So it was known as the harmonic law.[18]

Using Newton's Law of gravitation (published 1687), this relation can be found in the case of a circular orbit by setting the centripetal force equal to the gravitational force:

- mrω2=GmMr2{displaystyle mromega ^{2}=G{frac {mM}{r^{2}}}}

Then, expressing the angular velocity in terms of the orbital period and then rearranging, we find Kepler's Third Law:

- mr(2πT)2=GmMr2→T2=(4π2GM)r3→T2∝r3{displaystyle mrleft({frac {2pi }{T}}right)^{2}=G{frac {mM}{r^{2}}}rightarrow T^{2}=left({frac {4pi ^{2}}{GM}}right)r^{3}rightarrow T^{2}propto r^{3}}

A more detailed derivation can be done with general elliptical orbits, instead of circles, as well as orbiting the center of mass, instead of just the large mass. This results in replacing a circular radius, r{displaystyle r}

- a3T2=G(M+m)4π2≈GM4π2≈7.495⋅10−6(AU3days2) is constant{displaystyle {frac {a^{3}}{T^{2}}}={frac {G(M+m)}{4pi ^{2}}}approx {frac {GM}{4pi ^{2}}}approx 7.495cdot 10^{-6}left({frac {{text{AU}}^{3}}{{text{days}}^{2}}}right){text{ is constant}}}

where M{displaystyle M}

The following table shows the data used by Kepler to empirically derive his law:

| Planet | Mean distance to sun (AU) | Period (days) | R3T2{textstyle {frac {R^{3}}{T^{2}}}}  (106 AU3/day2) (106 AU3/day2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.389 | 87.77 | 7.64 |

| Venus | 0.724 | 224.70 | 7.52 |

| Earth | 1 | 365.25 | 7.50 |

| Mars | 1.524 | 686.95 | 7.50 |

| Jupiter | 5.2 | 4332.62 | 7.49 |

| Saturn | 9.510 | 10759.2 | 7.43 |

Upon finding this pattern Kepler wrote:[19]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

translated from "Harmonies of the World" by Kepler (1619)

Log-log plot of the semi-major axis (in Astronomical Units) versus the orbital period (in terrestrial years) for the eight planets of the Solar System.

For comparison, here are modern estimates:

| Planet | Semi-major axis (AU) | Period (days) | R3T2{textstyle {frac {R^{3}}{T^{2}}}}  (106 AU3/day2) (106 AU3/day2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.38710 | 87.9693 | 7.496 |

| Venus | 0.72333 | 224.7008 | 7.496 |

| Earth | 1 | 365.2564 | 7.496 |

| Mars | 1.52366 | 686.9796 | 7.495 |

| Jupiter | 5.20336 | 4332.8201 | 7.504 |

| Saturn | 9.53707 | 10775.599 | 7.498 |

| Uranus | 19.1913 | 30687.153 | 7.506 |

| Neptune | 30.0690 | 60190.03 | 7.504 |

Planetary acceleration

Isaac Newton computed in his Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica the acceleration of a planet moving according to Kepler's first and second law.

- The direction of the acceleration is towards the Sun.

- The magnitude of the acceleration is inversely proportional to the square of the planet's distance from the Sun (the inverse square law).

This implies that the Sun may be the physical cause of the acceleration of planets. However, Newton states in his Principia that he considers forces from a mathematical point of view, not a physical, thereby taking an instrumentalist view.[20] Moreover, he does not assign a cause to gravity.[21]

Newton defined the force acting on a planet to be the product of its mass and the acceleration (see Newton's laws of motion). So:

- Every planet is attracted towards the Sun.

- The force acting on a planet is directly proportional to the mass of the planet and is inversely proportional to the square of its distance from the Sun.

The Sun plays an unsymmetrical part, which is unjustified. So he assumed, in Newton's law of universal gravitation:

- All bodies in the solar system attract one another.

- The force between two bodies is in direct proportion to the product of their masses and in inverse proportion to the square of the distance between them.

As the planets have small masses compared to that of the Sun, the orbits conform approximately to Kepler's laws. Newton's model improves upon Kepler's model, and fits actual observations more accurately (see two-body problem).

Below comes the detailed calculation of the acceleration of a planet moving according to Kepler's first and second laws.

Acceleration vector

From the heliocentric point of view consider the vector to the planet r=rr^{displaystyle mathbf {r} =r{hat {mathbf {r} }}}

- dr^dt=r^˙=θ˙θ^,dθ^dt=θ^˙=−θ˙r^{displaystyle {frac {d{hat {mathbf {r} }}}{dt}}={dot {hat {mathbf {r} }}}={dot {theta }}{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}},qquad {frac {d{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}}{dt}}={dot {hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}}=-{dot {theta }}{hat {mathbf {r} }}}

where θ^{displaystyle {hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}}

Differentiate the position vector twice to obtain the velocity vector and the acceleration vector:

- r˙=r˙r^+rr^˙=r˙r^+rθ˙θ^,r¨=(r¨r^+r˙r^˙)+(r˙θ˙θ^+rθ¨θ^+rθ˙θ^˙)=(r¨−rθ˙2)r^+(rθ¨+2r˙θ˙)θ^.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{dot {mathbf {r} }}&={dot {r}}{hat {mathbf {r} }}+r{dot {hat {mathbf {r} }}}={dot {r}}{hat {mathbf {r} }}+r{dot {theta }}{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}},\{ddot {mathbf {r} }}&=left({ddot {r}}{hat {mathbf {r} }}+{dot {r}}{dot {hat {mathbf {r} }}}right)+left({dot {r}}{dot {theta }}{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}+r{ddot {theta }}{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}+r{dot {theta }}{dot {hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}}right)=left({ddot {r}}-r{dot {theta }}^{2}right){hat {mathbf {r} }}+left(r{ddot {theta }}+2{dot {r}}{dot {theta }}right){hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}.end{aligned}}}

So

- r¨=arr^+aθθ^{displaystyle {ddot {mathbf {r} }}=a_{r}{hat {boldsymbol {r}}}+a_{theta }{hat {boldsymbol {theta }}}}

where the radial acceleration is

- ar=r¨−rθ˙2{displaystyle a_{r}={ddot {r}}-r{dot {theta }}^{2}}

and the transversal acceleration is

- aθ=rθ¨+2r˙θ˙.{displaystyle a_{theta }=r{ddot {theta }}+2{dot {r}}{dot {theta }}.}

Inverse square law

Kepler's second law says that

- r2θ˙=nab{displaystyle r^{2}{dot {theta }}=nab}

is constant.

The transversal acceleration aθ{displaystyle a_{theta }}

- d(r2θ˙)dt=r(2r˙θ˙+rθ¨)=raθ=0.{displaystyle {frac {dleft(r^{2}{dot {theta }}right)}{dt}}=rleft(2{dot {r}}{dot {theta }}+r{ddot {theta }}right)=ra_{theta }=0.}

So the acceleration of a planet obeying Kepler's second law is directed towards the sun.

The radial acceleration ar{displaystyle a_{text{r}}}

- ar=r¨−rθ˙2=r¨−r(nabr2)2=r¨−n2a2b2r3.{displaystyle a_{text{r}}={ddot {r}}-r{dot {theta }}^{2}={ddot {r}}-rleft({frac {nab}{r^{2}}}right)^{2}={ddot {r}}-{frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{3}}}.}

Kepler's first law states that the orbit is described by the equation:

- pr=1+εcos(θ).{displaystyle {frac {p}{r}}=1+varepsilon cos(theta ).}

Differentiating with respect to time

- −pr˙r2=−εsin(θ)θ˙{displaystyle -{frac {p{dot {r}}}{r^{2}}}=-varepsilon sin(theta ),{dot {theta }}}

or

- pr˙=nabεsin(θ).{displaystyle p{dot {r}}=nab,varepsilon sin(theta ).}

Differentiating once more

- pr¨=nabεcos(θ)θ˙=nabεcos(θ)nabr2=n2a2b2r2εcos(θ).{displaystyle p{ddot {r}}=nabvarepsilon cos(theta ),{dot {theta }}=nabvarepsilon cos(theta ),{frac {nab}{r^{2}}}={frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{2}}}varepsilon cos(theta ).}

The radial acceleration ar{displaystyle a_{text{r}}}

- par=n2a2b2r2εcos(θ)−pn2a2b2r3=n2a2b2r2(εcos(θ)−pr).{displaystyle pa_{text{r}}={frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{2}}}varepsilon cos(theta )-p{frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{3}}}={frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{2}}}left(varepsilon cos(theta )-{frac {p}{r}}right).}

Substituting the equation of the ellipse gives

- par=n2a2b2r2(pr−1−pr)=−n2a2r2b2.{displaystyle pa_{text{r}}={frac {n^{2}a^{2}b^{2}}{r^{2}}}left({frac {p}{r}}-1-{frac {p}{r}}right)=-{frac {n^{2}a^{2}}{r^{2}}}b^{2}.}

The relation b2=pa{displaystyle b^{2}=pa}

- ar=−n2a3r2.{displaystyle a_{text{r}}=-{frac {n^{2}a^{3}}{r^{2}}}.}

This means that the acceleration vector r¨{displaystyle mathbf {ddot {r}} }

- r¨=−αr2r^{displaystyle mathbf {ddot {r}} =-{frac {alpha }{r^{2}}}{hat {mathbf {r} }}}

where

- α=n2a3{displaystyle alpha =n^{2}a^{3},}

is a constant, and r^{displaystyle {hat {mathbf {r} }}}

According to Kepler's third law, α{displaystyle alpha }

The inverse square law is a differential equation. The solutions to this differential equation include the Keplerian motions, as shown, but they also include motions where the orbit is a hyperbola or parabola or a straight line. See Kepler orbit.

Newton's law of gravitation

By Newton's second law, the gravitational force that acts on the planet is:

- F=mplanetr¨=−mplanetαr−2r^{displaystyle mathbf {F} =m_{text{planet}}mathbf {ddot {r}} =-m_{text{planet}}alpha r^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}}

where mplanet{displaystyle m_{text{planet}}}

- α=GmSun{displaystyle alpha =Gm_{text{Sun}}}

where G{displaystyle G}

The acceleration of solar system body number i is, according to Newton's laws:

- r¨i=G∑j≠imjrij−2r^ij{displaystyle mathbf {ddot {r}} _{i}=Gsum _{jneq i}m_{j}r_{ij}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{ij}}

where mj{displaystyle m_{j}}

In the special case where there are only two bodies in the world, Earth and Sun, the acceleration becomes

- r¨Earth=GmSunrEarth,Sun−2r^Earth,Sun{displaystyle mathbf {ddot {r}} _{text{Earth}}=Gm_{text{Sun}}r_{{text{Earth}},{text{Sun}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Earth}},{text{Sun}}}}

which is the acceleration of the Kepler motion. So this Earth moves around the Sun according to Kepler's laws.

If the two bodies in the world are Moon and Earth the acceleration of the Moon becomes

- r¨Moon=GmEarthrMoon,Earth−2r^Moon,Earth{displaystyle mathbf {ddot {r}} _{text{Moon}}=Gm_{text{Earth}}r_{{text{Moon}},{text{Earth}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Moon}},{text{Earth}}}}

So in this approximation the Moon moves around the Earth according to Kepler's laws.

In the three-body case the accelerations are

- r¨Sun=GmEarthrSun,Earth−2r^Sun,Earth+GmMoonrSun,Moon−2r^Sun,Moonr¨Earth=GmSunrEarth,Sun−2r^Earth,Sun+GmMoonrEarth,Moon−2r^Earth,Moonr¨Moon=GmSunrMoon,Sun−2r^Moon,Sun+GmEarthrMoon,Earth−2r^Moon,Earth{displaystyle {begin{aligned}mathbf {ddot {r}} _{text{Sun}}&=Gm_{text{Earth}}r_{{text{Sun}},{text{Earth}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Sun}},{text{Earth}}}+Gm_{text{Moon}}r_{{text{Sun}},{text{Moon}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Sun}},{text{Moon}}}\mathbf {ddot {r}} _{text{Earth}}&=Gm_{text{Sun}}r_{{text{Earth}},{text{Sun}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Earth}},{text{Sun}}}+Gm_{text{Moon}}r_{{text{Earth}},{text{Moon}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Earth}},{text{Moon}}}\mathbf {ddot {r}} _{text{Moon}}&=Gm_{text{Sun}}r_{{text{Moon}},{text{Sun}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Moon}},{text{Sun}}}+Gm_{text{Earth}}r_{{text{Moon}},{text{Earth}}}^{-2}{hat {mathbf {r} }}_{{text{Moon}},{text{Earth}}}end{aligned}}}

These accelerations are not those of Kepler orbits, and the three-body problem is complicated. But Keplerian approximation is the basis for perturbation calculations. See Lunar theory.

Position as a function of time

Kepler used his two first laws to compute the position of a planet as a function of time. His method involves the solution of a transcendental equation called Kepler's equation.

The procedure for calculating the heliocentric polar coordinates (r,θ) of a planet as a function of the time t since perihelion, is the following four steps:

- Compute the mean anomaly M = nt where n is the mean motion.

n⋅P=2π{displaystyle ncdot P=2pi }radians where P is the period.

- Compute the eccentric anomaly E by solving Kepler's equation:

- M=E−εsinE{displaystyle M=E-varepsilon sin E}

- M=E−εsinE{displaystyle M=E-varepsilon sin E}

- Compute the true anomaly θ by the equation:

- (1−ε)tan2θ2=(1+ε)tan2E2{displaystyle (1-varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {theta }{2}}=(1+varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {E}{2}}}

- (1−ε)tan2θ2=(1+ε)tan2E2{displaystyle (1-varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {theta }{2}}=(1+varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {E}{2}}}

- Compute the heliocentric distance

- r=a(1−εcosE).{displaystyle r=a(1-varepsilon cos E).}

- r=a(1−εcosE).{displaystyle r=a(1-varepsilon cos E).}

The Cartesian velocity vector can along be trivially calculated as v=μar⟨−sinE,1−ε2cosE⟩{displaystyle mathbf {v} ={frac {sqrt {mu a}}{r}}leftlangle -sin {E},{sqrt {1-varepsilon ^{2}}}cos {E}rightrangle }

The important special case of circular orbit, ε = 0, gives θ = E = M. Because the uniform circular motion was considered to be normal, a deviation from this motion was considered an anomaly.

The proof of this procedure is shown below.

Mean anomaly, M

FIgure 5: Geometric construction for Kepler's calculation of θ. The Sun (located at the focus) is labeled S and the planet P. The auxiliary circle is an aid to calculation. Line xd is perpendicular to the base and through the planet P. The shaded sectors are arranged to have equal areas by positioning of point y.

The Keplerian problem assumes an elliptical orbit and the four points:

s the Sun (at one focus of ellipse);

z the perihelion

c the center of the ellipse

p the planet

and

a=|cz|,{displaystyle a=|cz|,}distance between center and perihelion, the semimajor axis,

ε=|cs|a,{displaystyle varepsilon ={|cs| over a},}the eccentricity,

b=a1−ε2,{displaystyle b=a{sqrt {1-varepsilon ^{2}}},}the semiminor axis,

r=|sp|,{displaystyle r=|sp|,}the distance between Sun and planet.

θ=∠zsp,{displaystyle theta =angle zsp,}the direction to the planet as seen from the Sun, the true anomaly.

The problem is to compute the polar coordinates (r,θ) of the planet from the time since perihelion, t.

It is solved in steps. Kepler considered the circle with the major axis as a diameter, and

x,{displaystyle x,}the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle

y,{displaystyle y,}the point on the circle such that the sector areas |zcy| and |zsx| are equal,

M=∠zcy,{displaystyle M=angle zcy,}the mean anomaly.

The sector areas are related by |zsp|=ba⋅|zsx|.{displaystyle |zsp|={frac {b}{a}}cdot |zsx|.}

The circular sector area |zcy|=a2M2.{displaystyle |zcy|={frac {a^{2}M}{2}}.}

The area swept since perihelion,

- |zsp|=ba⋅|zsx|=ba⋅|zcy|=ba⋅a2M2=abM2,{displaystyle |zsp|={frac {b}{a}}cdot |zsx|={frac {b}{a}}cdot |zcy|={frac {b}{a}}cdot {frac {a^{2}M}{2}}={frac {abM}{2}},}

is by Kepler's second law proportional to time since perihelion. So the mean anomaly, M, is proportional to time since perihelion, t.

- M=nt,{displaystyle M=nt,,}

where n is the mean motion.

Eccentric anomaly, E

When the mean anomaly M is computed, the goal is to compute the true anomaly θ. The function θ = f(M) is, however, not elementary.[23] Kepler's solution is to use

E=∠zcx{displaystyle E=angle zcx}, x as seen from the centre, the eccentric anomaly

as an intermediate variable, and first compute E as a function of M by solving Kepler's equation below, and then compute the true anomaly θ from the eccentric anomaly E. Here are the details.

- |zcy|=|zsx|=|zcx|−|scx|a2M2=a2E2−aε⋅asinE2{displaystyle {begin{aligned}|zcy|&=|zsx|=|zcx|-|scx|\{frac {a^{2}M}{2}}&={frac {a^{2}E}{2}}-{frac {avarepsilon cdot asin E}{2}}end{aligned}}}

Division by a2/2 gives Kepler's equation

- M=E−εsinE.{displaystyle M=E-varepsilon sin E.}

This equation gives M as a function of E. Determining E for a given M is the inverse problem. Iterative numerical algorithms are commonly used.

Having computed the eccentric anomaly E, the next step is to calculate the true anomaly θ.

True anomaly, θ

Note from the figure that

- cd→=cs→+sd→{displaystyle {overrightarrow {cd}}={overrightarrow {cs}}+{overrightarrow {sd}}}

so that

- acosE=aε+rcosθ.{displaystyle acos E=avarepsilon +rcos theta .}

Dividing by a{displaystyle a}

- ra=1−ε21+εcosθ{displaystyle {frac {r}{a}}={frac {1-varepsilon ^{2}}{1+varepsilon cos theta }}}

to get

- cosE=ε+1−ε21+εcosθcosθ=ε(1+εcosθ)+(1−ε2)cosθ1+εcosθ=ε+cosθ1+εcosθ.{displaystyle cos E=varepsilon +{frac {1-varepsilon ^{2}}{1+varepsilon cos theta }}cos theta ={frac {varepsilon (1+varepsilon cos theta )+left(1-varepsilon ^{2}right)cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}={frac {varepsilon +cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}.}

The result is a usable relationship between the eccentric anomaly E and the true anomaly θ.

A computationally more convenient form follows by substituting into the trigonometric identity:

- tan2x2=1−cosx1+cosx.{displaystyle tan ^{2}{frac {x}{2}}={frac {1-cos x}{1+cos x}}.}

Get

- tan2E2=1−cosE1+cosE=1−ε+cosθ1+εcosθ1+ε+cosθ1+εcosθ=(1+εcosθ)−(ε+cosθ)(1+εcosθ)+(ε+cosθ)=1−ε1+ε⋅1−cosθ1+cosθ=1−ε1+εtan2θ2.{displaystyle {begin{aligned}tan ^{2}{frac {E}{2}}&={frac {1-cos E}{1+cos E}}={frac {1-{frac {varepsilon +cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}}{1+{frac {varepsilon +cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}}}\[8pt]&={frac {(1+varepsilon cos theta )-(varepsilon +cos theta )}{(1+varepsilon cos theta )+(varepsilon +cos theta )}}={frac {1-varepsilon }{1+varepsilon }}cdot {frac {1-cos theta }{1+cos theta }}={frac {1-varepsilon }{1+varepsilon }}tan ^{2}{frac {theta }{2}}.end{aligned}}}

Multiplying by 1 + ε gives the result

- (1−ε)tan2θ2=(1+ε)tan2E2{displaystyle (1-varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {theta }{2}}=(1+varepsilon )tan ^{2}{frac {E}{2}}}

This is the third step in the connection between time and position in the orbit.

Distance, r

The fourth step is to compute the heliocentric distance r from the true anomaly θ by Kepler's first law:

- r(1+εcosθ)=a(1−ε2){displaystyle r(1+varepsilon cos theta )=aleft(1-varepsilon ^{2}right)}

Using the relation above between θ and E the final equation for the distance r is:

- r=a(1−εcosE).{displaystyle r=a(1-varepsilon cos E).}

See also

- Circular motion

- Free-fall time

- Gravity

- Kepler orbit

- Kepler problem

- Kepler's equation

- Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector

Specific relative angular momentum, relatively easy derivation of Kepler's laws starting with conservation of angular momentum

Notes

^ Godefroy Wendelin wrote a letter to Giovanni Battista Riccioli about the relationship between the distances of the Jovian moons from Jupiter and the periods of their orbits, showing that the periods and distances conformed to Kepler's third law. See: Joanne Baptista Riccioli, Almagestum novum … (Bologna (Bononia), (Italy): Victor Benati, 1651), volume 1, page 492 Scholia III. In the margin beside the relevant paragraph is printed: Vendelini ingeniosa speculatio circa motus & intervalla satellitum Jovis. (Wendelin's clever speculation about the movement and distances of Jupiter's satellites.)

In 1621, Johannes Kepler had noted that Jupiter's moons obey (approximately) his third law in his Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae [Epitome of Copernican Astronomy] (Linz (“Lentiis ad Danubium“), (Austria): Johann Planck, 1622), book 4, part 2, page 554.

References

^ ab Bryant, Jeff; Pavlyk, Oleksandr. "Kepler's Second Law", Wolfram Demonstrations Project. Retrieved December 27, 2009.

^ https://www.nytimes.com/1990/01/23/science/after-400-years-a-challenge-to-kepler-he-fabricated-his-data-scholar-says.html?pagewanted=1

^ abc Holton, Gerald James; Brush, Stephen G. (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure: From Copernicus to Einstein and Beyond (3rd paperback ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. pp. 40–41. ISBN 0-8135-2908-5. Retrieved December 27, 2009..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Voltaire, Eléments de la philosophie de Newton [Elements of Newton's Philosophy] (London, England: 1738). See, for example:

From p. 162: "Par une des grandes loix de Kepler, toute Planete décrit des aires égales en temp égaux : par une autre loi non moins sûre, chaque Planete fait sa révolution autour du Soleil en telle sort, que si, sa moyenne distance au Soleil est 10. prenez le cube de ce nombre, ce qui sera 1000., & le tems de la révolution de cette Planete autour du Soleil sera proportionné à la racine quarrée de ce nombre 1000." (By one of the great laws of Kepler, each planet describes equal areas in equal times ; by another law no less certain, each planet makes its revolution around the sun in such a way that if its mean distance from the sun is 10, take the cube of that number, which will be 1000, and the time of the revolution of that planet around the sun will be proportional to the square root of that number 1000.)

From p. 205: "Il est donc prouvé par la loi de Kepler & par celle de Neuton, que chaque Planete gravite vers le Soleil, ... " (It is thus proved by the law of Kepler and by that of Newton, that each planet revolves around the sun … )

^ ab Wilson, Curtis (May 1994). "Kepler's Laws, So-Called" (PDF). HAD News. Washington, DC: Historical Astronomy Division, American Astronomical Society (31): 1–2. Retrieved December 27, 2016.

^ De la Lande, Astronomie, vol. 1 (Paris, France: Desaint & Saillant, 1764). See, for example:

From page 390: " … mais suivant la fameuse loi de Kepler, qui sera expliquée dans le Livre suivant (892), le rapport des temps périodiques est toujours plus grand que celui des distances, une planete cinq fois plus éloignée du soleil, emploie à faire sa révolution douze fois plus de temps ou environ; … " ( … but according to the famous law of Kepler, which will be explained in the following book [i.e., chapter] (paragraph 892), the ratio of the periods is always greater than that of the distances [so that, for example,] a planet five times farther from the sun, requires about twelve times or so more time to make its revolution [around the sun]; … )

From page 429: "Les Quarrés des Temps périodiques sont comme les Cubes des Distances. 892. La plus fameuse loi du mouvement des planetes découverte par Kepler, est celle du repport qu'il y a entre les grandeurs de leurs orbites, & le temps qu'elles emploient à les parcourir; … " (The squares of the periods are as the cubes of the distances. 892. The most famous law of the movement of the planets discovered by Kepler is that of the relation between the sizes of their orbits and the times that the [planets] require to traverse them; … )

From page 430: "Les Aires sont proportionnelles au Temps. 895. Cette loi générale du mouvement des planetes devenue si importante dans l'Astronomie, sçavior, que les aires sont proportionnelles au temps, est encore une des découvertes de Kepler; … " (Areas are proportional to times. 895. This general law of the movement of the planets [which has] become so important in astronomy, namely, that areas are proportional to times, is one of Kepler's discoveries; … )

From page 435: "On a appellé cette loi des aires proportionnelles aux temps, Loi de Kepler, aussi bien que celle de l'article 892, du nome de ce célebre Inventeur; … " (One called this law of areas proportional to times (the law of Kepler) as well as that of paragraph 892, by the name of that celebrated inventor; … )

^ Robert Small, An account of the astronomical discoveries of Kepler (London, England: J Mawman, 1804), pp. 298–299.

^ Robert Small, An account of the astronomical discoveries of Kepler (London, England: J. Mawman, 1804).

^ Bruce Stephenson (1994). Kepler's Physical Astronomy. Princeton University Press. p. 170. ISBN 0-691-03652-7.

^ In his Astronomia nova, Kepler presented only a proof that Mars' orbit is elliptical. Evidence that the other known planets' orbits are elliptical was presented only in 1621.

See: Johannes Kepler, Astronomia nova … (1609), p. 285. After having rejected circular and oval orbits, Kepler concluded that Mars' orbit must be elliptical. From the top of page 285: "Ergo ellipsis est Planetæ iter; … " (Thus, an ellipse is the planet's [i.e., Mars'] path; … ) Later on the same page: " … ut sequenti capite patescet: ubi simul etiam demonstrabitur, nullam Planetæ relinqui figuram Orbitæ, præterquam perfecte ellipticam; … " ( … as will be revealed in the next chapter: where it will also then be proved that any figure of the planet's orbit must be relinquished, except a perfect ellipse; … ) And then: "Caput LIX. Demonstratio, quod orbita Martis, … , fiat perfecta ellipsis: … " (Chapter 59. Proof that Mars' orbit, … , is a perfect ellipse: … ) The geometric proof that Mars' orbit is an ellipse appears as Protheorema XI on pages 289–290.

Kepler stated that every planet travels in elliptical orbits having the Sun at one focus in: Johannes Kepler, Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae [Summary of Copernican Astronomy] (Linz ("Lentiis ad Danubium"), (Austria): Johann Planck, 1622), book 5, part 1, III. De Figura Orbitæ (III. On the figure [i.e., shape] of orbits), pages 658–665. From p. 658: "Ellipsin fieri orbitam planetæ … " (Of an ellipse is made a planet's orbit … ). From p. 659: " … Sole (Foco altero huius ellipsis) … " ( … the Sun (the other focus of this ellipse) … ).

^ In his Astronomia nova ... (1609), Kepler did not present his second law in its modern form. He did that only in his Epitome of 1621. Furthermore, in 1609, he presented his second law in two different forms, which scholars call the "distance law" and the "area law".

- His "distance law" is presented in: "Caput XXXII. Virtutem quam Planetam movet in circulum attenuari cum discessu a fonte." (Chapter 32. The force that moves a planet circularly weakens with distance from the source.) See: Johannes Kepler, Astronomia nova … (1609), pp. 165–167. On page 167, Kepler states: " … , quanto longior est αδ quam αε, tanto diutius moratur Planeta in certo aliquo arcui excentrici apud δ, quam in æquali arcu excentrici apud ε." ( … , as αδ is longer than αε, so much longer will a planet remain on a certain arc of the eccentric near δ than on an equal arc of the eccentric near ε.) That is, the farther a planet is from the Sun (at the point α), the slower it moves along its orbit, so a radius from the Sun to a planet passes through equal areas in equal times. However, as Kepler presented it, his argument is accurate only for circles, not ellipses.

- His "area law" is presented in: "Caput LIX. Demonstratio, quod orbita Martis, … , fiat perfecta ellipsis: … " (Chapter 59. Proof that Mars' orbit, … , is a perfect ellipse: … ), Protheorema XIV and XV, pp. 291–295. On the top p. 294, it reads: "Arcum ellipseos, cujus moras metitur area AKN, debere terminari in LK, ut sit AM." (The arc of the ellipse, of which the duration is delimited [i.e., measured] by the area AKM, should be terminated in LK, so that it [i.e., the arc] is AM.) In other words, the time that Mars requires to move along an arc AM of its elliptical orbit is measured by the area of the segment AMN of the ellipse (where N is the position of the Sun), which in turn is proportional to the section AKN of the circle that encircles the ellipse and that is tangent to it. Therefore, the area that is swept out by a radius from the Sun to Mars as Mars moves along an arc of its elliptical orbit is proportional to the time that Mars requires to move along that arc. Thus, a radius from the Sun to Mars sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

In 1621, Kepler restated his second law for any planet: Johannes Kepler, Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae [Summary of Copernican Astronomy] (Linz ("Lentiis ad Danubium"), (Austria): Johann Planck, 1622), book 5, page 668. From page 668: "Dictum quidem est in superioribus, divisa orbita in particulas minutissimas æquales: accrescete iis moras planetæ per eas, in proportione intervallorum inter eas & Solem." (It has been said above that, if the orbit of the planet is divided into the smallest equal parts, the times of the planet in them increase in the ratio of the distances between them and the sun.) That is, a planet's speed along its orbit is inversely proportional to its distance from the Sun. (The remainder of the paragraph makes clear that Kepler was referring to what is now called angular velocity.)

^ ab Johannes Kepler, Harmonices Mundi [The Harmony of the World] (Linz, (Austria): Johann Planck, 1619), book 5, chapter 3, p. 189. From the bottom of p. 189: "Sed res est certissima exactissimaque quod proportio qua est inter binorum quorumcunque Planetarum tempora periodica, sit præcise sesquialtera proportionis mediarum distantiarum, … " (But it is absolutely certain and exact that the proportion between the periodic times of any two planets is precisely the sesquialternate proportion [i.e., the ratio of 3:2] of their mean distances, … ")

An English translation of Kepler's Harmonices Mundi is available as: Johannes Kepler with E.J. Aiton, A.M. Duncan, and J.V. Field, trans., The Harmony of the World (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: American Philosophical Society, 1997); see especially p. 411.

^ National Earth Science Teachers Association (9 October 2008). "Data Table for Planets and Dwarf Planets". Windows to the Universe. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

^ Wilbur Applebaum (13 June 2000). Encyclopedia of the Scientific Revolution: From Copernicus to Newton. Routledge. p. 603. ISBN 978-1-135-58255-5.

^ Roy Porter (25 September 1992). The Scientific Revolution in National Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-521-39699-8.

^ Victor Guillemin; Shlomo Sternberg (2006). Variations on a Theme by Kepler. American Mathematical Soc. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8218-4184-6.

^ Burtt, Edwin. The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science. p. 52.

^ Gerald James Holton, Stephen G. Brush (2001). Physics, the Human Adventure. Rutgers University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0-8135-2908-5.

^ Caspar, Max (1993). Kepler. New York: Dover.

^ I. Newton, Principia, p. 408 in the translation of I.B. Cohen and A. Whitman

^ I. Newton, Principia, p. 943 in the translation of I.B. Cohen and A. Whitman

^ Schwarz, René. "Memorandum № 1: Keplerian Orbit Elements → Cartesian State Vectors" (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2018.

^ MÜLLER, M (1995). "EQUATION OF TIME – PROBLEM IN ASTRONOMY". Acta Physica Polonica A. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Kepler's life is summarized on pages 523–627 and Book Five of his magnum opus, Harmonice Mundi (harmonies of the world), is reprinted on pages 635–732 of On the Shoulders of Giants: The Great Works of Physics and Astronomy (works by Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Newton, and Einstein). Stephen Hawking, ed. 2002

ISBN 0-7624-1348-4

- A derivation of Kepler's third law of planetary motion is a standard topic in engineering mechanics classes. See, for example, pages 161–164 of Meriam, J. L. (1971) [1966]. "Dynamics, 2nd ed". New York: John Wiley. ISBN 0-471-59601-9..

- Murray and Dermott, Solar System Dynamics, Cambridge University Press 1999,

ISBN 0-521-57597-4

- V.I. Arnold, Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Chapter 2. Springer 1989,

ISBN 0-387-96890-3

External links

- B.Surendranath Reddy; animation of Kepler's laws: applet

- "Derivation of Kepler's Laws" (from Newton's laws) at Physics Stack Exchange.

- Crowell, Benjamin, Light and Matter, an online book that gives a proof of the first law without the use of calculus (see section 15.7)

- David McNamara and Gianfranco Vidali, Kepler's Second Law – Java Interactive Tutorial, https://web.archive.org/web/20060910225253/http://www.phy.syr.edu/courses/java/mc_html/kepler.html, an interactive Java applet that aids in the understanding of Kepler's Second Law.

- Audio – Cain/Gay (2010) Astronomy Cast Johannes Kepler and His Laws of Planetary Motion

- University of Tennessee's Dept. Physics & Astronomy: Astronomy 161 page on Johannes Kepler: The Laws of Planetary Motion [1]

- Equant compared to Kepler: interactive model [2]

- Kepler's Third Law:interactive model [3]

- Solar System Simulator (Interactive Applet)

Kepler and His Laws, educational web pages by David P. Stern

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}r_{max }-a&=a-r_{min }\[3pt]a&={frac {p}{1-varepsilon ^{2}}}end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1d244bc984688866186efa8db808525b0cc93d55)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {r_{max }}{b}}&={frac {b}{r_{min }}}\[3pt]b&={frac {p}{sqrt {1-varepsilon ^{2}}}}end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52d5542ac3ab20bcfa4bfc38e00663278f2cb00c)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}{frac {1}{r_{min }}}-{frac {1}{p}}&={frac {1}{p}}-{frac {1}{r_{max }}}\[3pt]pa&=r_{max }r_{min }=b^{2},end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e9f73c1282d2cbce584d6b86d1ee0ff9ab47d731)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}tan ^{2}{frac {E}{2}}&={frac {1-cos E}{1+cos E}}={frac {1-{frac {varepsilon +cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}}{1+{frac {varepsilon +cos theta }{1+varepsilon cos theta }}}}\[8pt]&={frac {(1+varepsilon cos theta )-(varepsilon +cos theta )}{(1+varepsilon cos theta )+(varepsilon +cos theta )}}={frac {1-varepsilon }{1+varepsilon }}cdot {frac {1-cos theta }{1+cos theta }}={frac {1-varepsilon }{1+varepsilon }}tan ^{2}{frac {theta }{2}}.end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1bc0a064e24ecffca17176902230ccd78625ad9a)