Ravenna

Ravenna (Italian pronunciation: [raˈvenna], also locally [raˈvɛnna] (![]() listen); Romagnol: Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 402 until that empire collapsed in 476. It then served as the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom until it was re-conquered in 540 by the Byzantine Empire. Afterwards, the city formed the centre of the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna until the invasion of the Lombards in 751, after which it became the seat of the Kingdom of the Lombards.

listen); Romagnol: Ravèna) is the capital city of the Province of Ravenna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy. It was the capital city of the Western Roman Empire from 402 until that empire collapsed in 476. It then served as the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom until it was re-conquered in 540 by the Byzantine Empire. Afterwards, the city formed the centre of the Byzantine Exarchate of Ravenna until the invasion of the Lombards in 751, after which it became the seat of the Kingdom of the Lombards.

Although it is an inland city, Ravenna is connected to the Adriatic Sea by the Candiano Canal. It is known for its well-preserved late Roman and Byzantine architecture, and has eight UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Ancient era

1.2 Exarchate of Ravenna

1.3 Middle Ages and Renaissance

1.4 Modern age

2 Government

3 Architecture

4 Music

5 Ravenna in literature

6 Ravenna in film

7 Transport

8 Amusement parks

9 Twin towns

10 Sports

11 Notable people

12 References

13 Sources

14 External links

History

The origin of the name Ravenna is unclear, although it is believed the name is Etruscan.[3] Some have speculated that "ravenna" is related to "Rasenna" (later "Rasna"), the term that the Etruscans used for themselves, but there is no agreement on this point.[citation needed]

Ancient era

The origins of Ravenna are uncertain.[4] The first settlement is variously attributed to (and then has seen the copresence of) the Thessalians, the Etruscans and the Umbrians. Afterwards its territory was settled also by the Senones, especially the southern countryside of the city (that wasn't part of the lagoon), the Ager Decimanus. Ravenna consisted of houses built on piles on a series of small islands in a marshy lagoon – a situation similar to Venice several centuries later. The Romans ignored it during their conquest of the Po River Delta, but later accepted it into the Roman Republic as a federated town in 89 BC. In 49 BC, it was the location where Julius Caesar gathered his forces before crossing the Rubicon. Later, after his battle against Mark Antony in 31 BC, Emperor Augustus founded the military harbor of Classe.[5] This harbor, protected at first by its own walls, was an important station of the Roman Imperial Fleet. Nowadays the city is landlocked, but Ravenna remained an important seaport on the Adriatic until the early Middle Ages. During the German campaigns, Thusnelda, widow of Arminius, and Marbod, King of the Marcomanni, were confined at Ravenna.

The city of Ravenna in the 4th century as shown on the Peutinger Map

Ravenna greatly prospered under Roman rule. Emperor Trajan built a 70 km (43.50 mi) long aqueduct at the beginning of the 2nd century. During the Marcomannic Wars, Germanic settlers in Ravenna revolted and managed to seize possession of the city. For this reason, Marcus Aurelius decided not only against bringing more barbarians into Italy, but even banished those who had previously been brought there.[6] In AD 402, Emperor Honorius transferred the capital of the Western Roman Empire from Milan to Ravenna. At that time it was home to 50,000 people.[7] The transfer was made partly for defensive purposes: Ravenna was surrounded by swamps and marshes, and was perceived to be easily defensible (although in fact the city fell to opposing forces numerous times in its history); it is also likely that the move to Ravenna was due to the city's port and good sea-borne connections to the Eastern Roman Empire. However, in 409, King Alaric I of the Visigoths simply bypassed Ravenna, and went on to sack Rome in 410 and to take Galla Placidia, daughter of Emperor Theodosius I, hostage. After many vicissitudes, Galla Placidia returned to Ravenna with her son, Emperor Valentinian III, due to the support of her nephew Theodosius II. Ravenna enjoyed a period of peace, during which time the Christian religion was favoured by the imperial court, and the city gained some of its most famous monuments, including the Orthodox Baptistery, the misnamed Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (she was not actually buried there), and San Giovanni Evangelista.

The late 5th century saw the dissolution of Roman authority in the west, and the last person to hold the title of emperor in the West was deposed in 476 by the general Odoacer. Odoacer ruled as King of Italy for 13 years, but in 489 the Eastern Emperor Zeno sent the Ostrogoth King Theoderic the Great to re-take the Italian peninsula. After losing the Battle of Verona, Odoacer retreated to Ravenna, where he withstood a siege of three years by Theoderic, until the taking of Rimini deprived Ravenna of supplies. Theoderic took Ravenna in 493, supposedly slew Odoacer with his own hands, and Ravenna became the capital of the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy. Theoderic, following his imperial predecessors, also built many splendid buildings in and around Ravenna, including his palace church Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, an Arian cathedral (now Santo Spirito) and Baptistery, and his own Mausoleum just outside the walls.

The Mausoleum of Theoderic.

Both Odoacer and Theoderic and their followers were Arian Christians, but co-existed peacefully with the Latins, who were largely Orthodox. Ravenna's Orthodox bishops carried out notable building projects, of which the sole surviving one is the Capella Arcivescovile. Theoderic allowed Roman citizens within his kingdom to be subject to Roman law and the Roman judicial system. The Goths, meanwhile, lived under their own laws and customs. In 519, when a mob had burned down the synagogues of Ravenna, Theoderic ordered the town to rebuild them at its own expense.

Theoderic died in 526 and was succeeded by his young grandson Athalaric under the authority of his daughter Amalasunta, but by 535 both were dead and Theoderic's line was represented only by Amalasuntha's daughter Matasuntha. Various Ostrogothic military leaders took the Kingdom of Italy, but none were as successful as Theoderic had been. Meanwhile, the orthodox Christian Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, opposed both Ostrogoth rule and the Arian variety of Christianity. In 535 his general Belisarius invaded Italy and in 540 conquered Ravenna. After the conquest of Italy was completed in 554, Ravenna became the seat of Byzantine government in Italy.

From 540 to 600, Ravenna's bishops embarked upon a notable building program of churches in Ravenna and in and around the port city of Classe. Surviving monuments include the Basilica of San Vitale and the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, as well as the partially surviving San Michele in Africisco.

Exarchate of Ravenna

Transfiguration of Jesus. Allegorical image with Crux gemmata and lambs represent apostles, 533–549, apse of Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe

Following the conquests of Belisarius for the Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, Ravenna became the seat of the Byzantine governor of Italy, the Exarch, and was known as the Exarchate of Ravenna. It was at this time that the Ravenna Cosmography was written.

Under Byzantine rule, the archbishop of the Archdiocese of Ravenna was temporarily granted autocephaly from the Roman Church by the emperor, in 666, but this was soon revoked. Nevertheless, the archbishop of Ravenna held the second place in Italy after the pope, and played an important role in many theological controversies during this period.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

The Lombards, under King Liutprand, occupied Ravenna in 712, but were forced to return it to the Byzantines.[8] However, in 751 the Lombard king, Aistulf, succeeded in conquering Ravenna, thus ending Byzantine rule in northern Italy.

King Pepin of the Franks attacked the Lombards under orders of Pope Stephen II. Ravenna then gradually came under the direct authority of the Popes, although this was contested by the archbishops at various times. Pope Adrian I authorized Charlemagne to take away anything from Ravenna that he liked, and an unknown quantity of Roman columns, mosaics, statues, and other portable items were taken north to enrich his capital of Aachen.

In 1198 Ravenna led a league of Romagna cities against the Emperor, and the Pope was able to subdue it. After the war of 1218 the Traversari family was able to impose its rule in the city, which lasted until 1240. After a short period under an Imperial vicar, Ravenna was returned to the Papal States in 1248 and again to the Traversari until, in 1275, the Da Polenta established their long-lasting seigniory. One of the most illustrious residents of Ravenna at this time was the exiled poet Dante. The last of the Da Polenta, Ostasio III, was ousted by the Republic of Venice in 1440, and the city was annexed to the Venetian territories.

Ravenna was ruled by Venice until 1509, when the area was invaded in the course of the Italian Wars. In 1512, during the Holy League wars, Ravenna was sacked by the French following the Battle of Ravenna. Ravenna was also known during the Renaissance as the birthplace of the Monster of Ravenna.

After the Venetian withdrawal, Ravenna was again ruled by legates of the Pope as part of the Papal States. The city was damaged in a tremendous flood in May 1636. Over the next 300 years, a network of canals diverted nearby rivers and drained nearby swamps, thus reducing the possibility of flooding and creating a large belt of agricultural land around the city.

Modern age

Apart from another short occupation by Venice (1527–1529), Ravenna was part of the Papal States until 1796, when it was annexed to the French puppet state of the Cisalpine Republic, (Italian Republic from 1802, and Kingdom of Italy from 1805). It was returned to the Papal States in 1814. Occupied by Piedmontese troops in 1859, Ravenna and the surrounding Romagna area became part of the new unified Kingdom of Italy in 1861. During World War II, troops of the British 27th Lancers entered and occupied Ravenna on 5 December 1944. The town suffered very little damage.

Government

Architecture

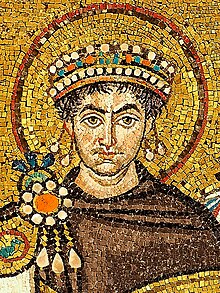

Basilica of San Vitale - triumphal arch mosaics.

Garden of Eden mosaic in mausoleum of Galla Placidia. 5th century CE.

Arian Baptistry ceiling mosaic.

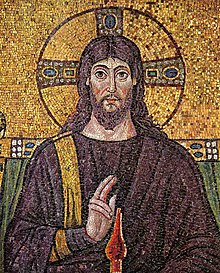

6th-century mosaic in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna portrays Jesus long-haired and bearded, dressed in Byzantinian style.

The Arian Baptistry.

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

The so-called "Mausoleum of Galla Placidia" in Ravenna.

Mosaic of the Palace of Theoderic in Sant'Apollinare Nuovo.

Eight early Christian monuments of Ravenna are inscribed on the World Heritage List. These are

Orthodox Baptistry also called Baptistry of Neon (c. 430)

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (c. 430)

Arian Baptistry (c. 500)

Archiepiscopal Chapel (c. 500)

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo (c. 500)

Mausoleum of Theoderic (520)

Basilica of San Vitale (548)

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe (549)

Other attractions include:

- The church of St. John the Evangelist is from the 5th century, erected by Galla Placidia after she survived a storm at sea. It was restored after the World War II bombings. The belltower contains four bells, the two majors dating back to 1208.

- The 6th-century church of the Spirito Santo, which has been quite drastically altered since the 6th century. It was originally the Arian cathedral. The façade has a 16th-century portico with five arcades.

- The St. Francis basilica, rebuilt in the 10th–11th centuries over a precedent edifice dedicated to the Apostles and later to St. Peter. Behind the humble brick façade, it has a nave and two aisles. Fragments of mosaics from the first church are visible on the floor, which is usually covered by water after heavy rains (together with the crypt). Here the funeral ceremony of Dante Alighieri was held in 1321. The poet is buried in a tomb annexed to the church, the local authorities having resisted for centuries all demands by Florence for return of the remains of its most famous exile.

- The Baroque church of Santa Maria Maggiore (525–532, rebuilt in 1671). It houses a picture by Luca Longhi.

- The church of San Giovanni Battista (1683), also in Baroque style, with a Middle Ages campanile.

- The basilica of Santa Maria in Porto (16th century), with a rich façade from the 18th century. It has a nave and two aisles, with a high cupola. It houses the image of famous Greek Madonna, which was allegedly brought to Ravenna from Constantinople.

- The nearby Communal Gallery has various works from Romagnoli painters.

- The Rocca Brancaleone ("Brancaleone Castle"), built by the Venetians in 1457. Once part of the city walls, it is now a public park. It is divided into two parts: the true Castle and the Citadel, the latter having an extent of 14,000 m2 (150,694.75 sq ft).

- The "so-called Palace of Theoderic", in fact the entrance to the former church of San Salvatore. It includes mosaics from the true palace of the Ostrogoth king.

- The church of Sant'Eufemia (18th century), gives access to the so-called Stone Carpets Domus (6th–7th century): this houses splendid mosaics from a Byzantine palace.

- The National Museum.

- The Archiepiscopal Museum

Music

The city annually hosts the Ravenna Festival, one of Italy's prominent classical music gatherings. Opera performances are held at the Teatro Alighieri while concerts take place at the Palazzo Mauro de André as well as in the ancient Basilica of San Vitale and Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe. Chicago Symphony Orchestra music director Riccardo Muti, a longtime resident of the city, regularly participates in the festival, which invites orchestras and other performers from around the world.

Ravenna in literature

- Pre-1800

- The city is mentioned in Canto V in Dante's Inferno.

- Also in the 16th century, Nostradamus provides four prophecies:

- "The Magnavacca (canal) at Ravenna in great trouble, Canals by fifteen shut up at Fornase", in reference to fifteen French sabateurs.[9]

- As the place of a battle extending to Perugia and a sacred escape in its aftermath, leaving rotting horses left to eat

- In relation to the snatching of a lady "near Ravenna" and then the legate of Lisbon seizing 70 souls at sea

- Ravenna is one of three-similarly named contenders for the birth of the third and final Antichrist who enslaves Slovenia (see Ravne na Koroškem)[10]

- "The Magnavacca (canal) at Ravenna in great trouble, Canals by fifteen shut up at Fornase", in reference to fifteen French sabateurs.[9]

- Ravenna is the setting for The Witch, a play by Thomas Middleton (1580–1627)

- Post-1800

Lord Byron lived in Ravenna between 1819 and 1821, led by the love for a local aristocratic and married young woman, Teresa Guiccioli. Here he continued Don Juan and wrote:

Ravenna Diary, My Dictionary and Recollections.[11]

Oscar Wilde (1854–1900) wrote a poem Ravenna in 1878.[12]

- Symbolist, lyrical poet Alexander Blok (1880–1921) wrote a poem entitled Ravenna (May–June 1909) inspired by his Italian journey (spring 1909).

- During his travels, German poet and philosopher Hermann Hesse (1877–1962) came across Ravenna and was inspired to write two poems of the city. They are entitled Ravenna (1) and Ravenna (2).

T. S. Eliot's (1888–1965) poem "Lune de Miel" (written in French) describes a honeymooning couple from Indiana sleeping not far from the ancient Basilica of Sant' Apollinare in Classe (just outside Ravenna), famous for the carved capitals of its columns, which depict acanthus leaves buffeted by the wind, unlike the leaves in repose on similar columns elsewhere.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973) may have based his city of Minas Tirith at least in part on Ravenna.[13]

Ravenna in film

Michelangelo Antonioni filmed his 1964 movie Red Desert (Deserto Rosso) within the industrialised areas of the Pialassa valley within the city limits.

Transport

Ravenna has an important commercial and tourist port.

Ravenna railway station has direct Trenitalia service to Bologna, Ferrara, Lecce, Milan, Parma, Rimini, and Verona.

Ravenna Airport is located in Ravenna. The nearest commercial airports are those of Forlì, Rimini and Bologna.

Freeways crossing Ravenna include: A14-bis from the hub of Bologna; on the north-south axis of EU routes E45 (from Rome) and E55 (SS-309 "Romea" from Venice); and on the regional Ferrara-Rimini axis of SS-16 (partially called "Adriatica").

Amusement parks

- Mirabilandia

- Safari Ravenna

Twin towns

Ravenna is twinned with:

Chichester, United Kingdom

Chichester, United Kingdom

Dubrovnik, Croatia, since 1969

Dubrovnik, Croatia, since 1969

Speyer, Germany, since 1989

Speyer, Germany, since 1989

Chartres, France, since 1957

Chartres, France, since 1957

Tønsberg, Norway

Tønsberg, Norway

Szekszárd, Hungary

Szekszárd, Hungary

Laguna, Brazil

Laguna, Brazil

Sports

The historical Italian football of the city is Ravenna F.C. Currently it plays in Eccellenza Emilia-Romagna Girone B.

A.P.D. Ribelle 1927 is the Italian football of Castiglione di Ravenna, a fraction of Ravenna and was founded in 1927. Currently it plays in Italy's Serie D after promotion from Eccellenza Emilia-Romagna Girone B in the 2013-14 season.

The president is Marcello Missiroli and the manager is Enrico Zaccaroni.

Its home ground is Stadio Massimo Sbrighi of the fraction with 1,000 seats. The team's colors are white and blue.

The beaches of Ravenna hosted the 2011 FIFA Beach Soccer World Cup, in September 2011.

Notable people

Francesco Ingoli, Theatine scientist and lawyer

Peter Damian, Catholic Saint and Cardinal

References

- Notes

^ GeoDemo - Istat.it

^ Generally speaking, adjectival "Ravenna" and "Ravennate" are more common for most adjectival uses—the Ravenna Cosmography, Ravenna grass, the Ravennate fleet—while "Ravennese" is more common in reference to people. The neologism "Ravennan" is also encountered. The Italian form is ravennate; in Latin, Ravennatus, Ravennatis, and Ravennatensis are all encountered.

^ Tourism in Ravenna – Official site – History. Turismo.ravenna.it (2010-06-20). Retrieved on 2011-06-20.

^ Deborah M. Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2010), for this and much of the information that follows

^ From classis, Latin "fleet".

^ Dio 72.11.4-5; Birley, Marcus Aurelius

^ https://www.academia.edu/1166147/_The_Fall_and_Decline_of_the_Roman_Urban_Mind_

^ Noble, Thomas F. X. (1984). The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680–825. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1239-8..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Jones, Tom (2012). Nostradamus. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing. ISBN 9781434918239.

^ Reading, Mario (2009). The Complete Prophesies of Nostradamus. London: Watkins Publishing. ISBN 9781906787394.

^ "Sito Ufficiale – Ufficio Turismo del Comune di Ravenna – I grandi scrittori". Turismo.ra.it. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

^ Ravenna

^ https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/23/jrr-tolkien-middle-earth-annotated-map-blackwells-lord-of-the-rings?CMP=fb_gu

Sources

- See also: Bibliography of the history of Ravenna

- Janet Nelson, Judith Herrin, Ravenna: its role in earlier medieval change and exchange, London, Institute of Historical Research, 2016,

ISBN 9781909646148

External links

- Ravenna - Catholic encyclopedia

Tourism and culture Official website (in Italian) (in English)

Ravenna, A Study (1913) by Edward Hutton, from Project Gutenberg

- Ravenna's early history and its monuments - Catholic Encyclopedia

Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace Ravenna Pages (photos)- Deborah M. Deliyannis, Ravenna in Late Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2010)