Track (rail transport)

| Track gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

By transport mode | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tram · Rapid transit Miniature · Scale model | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By size (list) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Change of gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Break-of-gauge · Dual gauge · Conversion (list) · Bogie exchange · Variable gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By location | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

North America · South America · Europe · Australia  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Rail transport |

|---|

|

|

|

The track on a railway or railroad, also known as the permanent way, is the structure consisting of the rails, fasteners, railroad ties (sleepers, British English) and ballast (or slab track), plus the underlying subgrade. It enables trains to move by providing a dependable surface for their wheels to roll upon. For clarity it is often referred to as railway track (British English and UIC terminology) or railroad track (predominantly in the United States). Tracks where electric trains or electric trams run are equipped with an electrification system such as an overhead electrical power line or an additional electrified rail.

The term permanent way also refers to the track in addition to lineside structures such as fences.

Contents

1 Structure

1.1 Traditional track structure

1.2 Ballastless track

1.3 Continuous longitudinally supported track

2 Rail

2.1 Wooden rails

2.2 Rail classification (weight)

3 Joining rails

3.1 Jointed track

3.1.1 Insulated joints

3.2 Continuous welded rail

4 Sleepers

4.1 Fixing rails to sleepers

5 Portable track

6 Layout

6.1 Gauge

7 Maintenance

8 Bed and foundation

9 Historical development

10 See also

11 References

12 Bibliography

13 External links

Structure

Traditional track structure

Railway track (new) showing traditional features of ballast, part of sleeper and fixing mechanisms

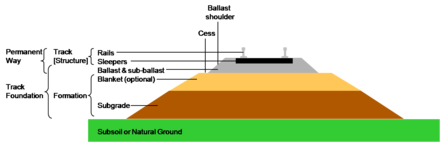

Section through railway track and foundation showing the ballast and formation layers. The layers are slightly sloped to help drainage.

Sometimes there is a layer of rubber matting (not shown) to improve drainage, and to dampen sound and vibration.

Notwithstanding modern technical developments, the overwhelmingly dominant track form worldwide consists of flat-bottom steel rails supported on timber or pre-stressed concrete sleepers, which are themselves laid on crushed stone ballast.

Most railroads with heavy traffic utilize continuously welded rails supported by sleepers attached via base plates that spread the load. A plastic or rubber pad is usually placed between the rail and the tie plate where concrete sleepers are used. The rail is usually held down to the sleeper with resilient fastenings, although cut spikes are widely used in North American practice. For much of the 20th century, rail track used softwood timber sleepers and jointed rails, and a considerable extent of this track type remains on secondary and tertiary routes. The rails were typically of flat bottom section fastened to the sleepers with dog spikes through a flat tie plate in North America and Australia, and typically of bullhead section carried in cast iron chairs in British and Irish practice. The London, Midland and Scottish Railway pioneered the conversion to flat-bottomed rail and the supposed advantage of bullhead rail - that the rail could be turned over and re-used when the top surface had become worn - turned out to be unworkable in practice because the underside was usually ruined by fretting from the chairs.

Jointed rails were used at first because contemporary technology did not offer any alternative. However, the intrinsic weakness in resisting vertical loading results in the ballast becoming depressed and a heavy maintenance workload is imposed to prevent unacceptable geometrical defects at the joints. The joints also needed to be lubricated, and wear at the fishplate (joint bar) mating surfaces needed to be rectified by shimming. For this reason jointed track is not financially appropriate for heavily operated railroads.

Timber sleepers are of many available timbers, and are often treated with creosote, copper-chrome-arsenate, or other wood preservative. Pre-stressed concrete sleepers are often used where timber is scarce and where tonnage or speeds are high. Steel is used in some applications.

The track ballast is customarily crushed stone, and the purpose of this is to support the sleepers and allow some adjustment of their position, while allowing free drainage.

Ballastless track

Track of Singapore LRT

Ballastless high-speed track in China

A disadvantage of traditional track structures is the heavy demand for maintenance, particularly surfacing (tamping) and lining to restore the desired track geometry and smoothness of vehicle running. Weakness of the subgrade and drainage deficiencies also lead to heavy maintenance costs. This can be overcome by using ballastless track. In its simplest form this consists of a continuous slab of concrete (like a highway structure) with the rails supported directly on its upper surface (using a resilient pad).

There are a number of proprietary systems, and variations include a continuous reinforced concrete slab, or alternatively the use of pre-cast pre-stressed concrete units laid on a base layer. Many permutations of design have been put forward.

However, ballastless track has a high initial cost, and in the case of existing railroads the upgrade to such requires closure of the route for a long period. Its whole-life cost can be lower because of the reduction in maintenance. Ballastless track is usually considered for new very high speed or very high loading routes, in short extensions that require additional strength (e.g. railway stations), or for localised replacement where there are exceptional maintenance difficulties, for example in tunnels. Some rubber-tyred metros use ballastless tracks.[1]

Continuous longitudinally supported track

Early railways (c. 1840s) experimented with continuous bearing railtrack, in which the rail was supported along its length, with examples including Brunel's baulk road on the Great Western Railway, as well as use on the Newcastle and North Shields Railway,[2] on the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to a design by John Hawkshaw, and elsewhere.[3] Continuous-bearing designs were also promoted by other engineers.[4] The system was trialled on the Baltimore and Ohio railway in the 1840s, but was found to be more expensive to maintain than rail with cross sleepers.[5]

Later applications of continuously supported track include Balfour Beatty's 'embedded slab track', which uses a rounded rectangular rail profile (BB14072) embedded in a slipformed (or pre-cast) concrete base (development 2000s).[6][7] The 'embedded rail structure', used in the Netherlands since 1976, initially used a conventional UIC 54 rail embedded in concrete, and later developed (late 1990s) to use a 'mushroom' shaped SA42 rail profile; a version for light rail using a rail supported in an asphalt concrete–filled steel trough has also been developed (2002).[8]

Ladder track at Shinagawa Station, Tokyo, Japan

Diagram of cross section of 1830s ladder type track used on the Leeds and Selby Railway

Modern ladder track can be considered a development of baulk road. Ladder track utilizes sleepers aligned along the same direction as the rails with rung-like gauge restraining cross members. Both ballasted and ballastless types exist.

Rail

Cross-sections of flat-bottomed rail, which can rest directly on the sleepers, and bullhead rail which sits in a chair (not shown)

Modern track typically uses hot-rolled steel with a profile of an asymmetrical rounded I-beam.[9] Unlike some other uses of iron and steel, railway rails are subject to very high stresses and have to be made of very high-quality steel alloy. It took many decades to improve the quality of the materials, including the change from iron to steel. The stronger the rails and the rest of the trackwork, the heavier and faster the trains the track can carry.

Other profiles of rail include: bullhead rail; grooved rail; "flat-bottomed rail" (Vignoles rail or flanged T-rail); bridge rail (inverted U–shaped used in baulk road); and Barlow rail (inverted V).

North American railroads until the mid- to late-20th century used rails 39 ft (11.89 m) long so they could be carried in gondola cars (open wagons), often 40 ft (12.2 m) long; as gondola sizes increased, so did rail lengths.

According to the Railway Gazette the planned-but-cancelled 150-kilometre rail line for the Baffinland Iron Mine, on Baffin Island, would have used older carbon steel alloys for its rails, instead of more modern, higher performance alloys, because modern alloy rails can become brittle at very low temperatures.[10]

Wooden rails

The earliest rails were made of wood, which wore out quickly. Hardwood such as jarrah and karri were better than softwoods such as fir. Longitudinal sleepers such as Brunel's baulk road are topped with iron or steel rails that are lighter than they might otherwise be because of the support of the sleepers.

Early North American railroads used iron on top of wooden rails as an economy measure but gave up this method of construction after the iron came loose, began to curl and went into the floors of the coaches. The iron strap rail coming through the floors of the coaches came to be referred to as "snake heads" by early railroaders.[11][12]

Rail classification (weight)

Rail is graded by weight over a standard length. Heavier rail can support greater axle loads and higher train speeds without sustaining damage than lighter rail, but at a greater cost. In North America and the United Kingdom, rail is graded by its linear density in pounds per yard (usually shown as pound or lb), so 130-pound rail would weigh 130 lb/yd (64 kg/m). The usual range is 115 to 141 lb/yd (57 to 70 kg/m). In Europe, rail is graded in kilograms per metre and the usual range is 40 to 60 kg/m (81 to 121 lb/yd). The heaviest rail mass-produced was 155 pounds per yard (77 kg/m) and was rolled for the Pennsylvania Railroad. The United Kingdom is in the process of transition from the imperial to metric rating of rail.[citation needed]

Joining rails

Rails are produced in fixed lengths and need to be joined end-to-end to make a continuous surface on which trains may run. The traditional method of joining the rails is to bolt them together using metal fishplates (jointbars in the US), producing jointed track. For more modern usage, particularly where higher speeds are required, the lengths of rail may be welded together to form continuous welded rail (CWR).

Jointed track

Bonded main line 6-bolt rail joint on a segment of 155 lb/yd (76.9 kg/m) rail. Note how adjacent bolts are oppositely oriented to prevent complete separation of the joint in the event of being struck by a wheel during a derailment.

Jointed track is made using lengths of rail, usually around 20 m (66 ft) long (in the UK) and 39 or 78 ft (12 or 24 m) long (in North America), bolted together using perforated steel plates known as fishplates (UK) or joint bars (North America).

Fishplates are usually 600 mm (2 ft) long, used in pairs either side of the rail ends and bolted together (usually four, but sometimes six bolts per joint). The bolts may be oppositely-oriented so that in the event of a derailment and a wheel flange striking the joint, only some of the bolts will be sheared, reducing the likelihood of the rails misaligning with each other and exacerbating the seriousness of the derailment. This technique is not applied universally, European practice being to have all the bolt heads on the same side of the rail. Small gaps which function as expansion joints are deliberately left between the rail ends to allow for expansion of the rails in hot weather. European practice was to have the rail joints on both rails adjacent to each other, while North American practice is to stagger them.

Because of the small gaps left between the rails, when trains pass over jointed tracks they make a "clickety-clack" sound. Unless it is well-maintained, jointed track does not have the ride quality of welded rail and is less desirable for high speed trains. However, jointed track is still used in many countries on lower speed lines and sidings, and is used extensively in poorer countries due to the lower construction cost and the simpler equipment required for its installation and maintenance.

A major problem of jointed track is cracking around the bolt holes, which can lead to breaking of the rail head (the running surface). This was the cause of the Hither Green rail crash which caused British Railways to begin converting much of its track to continuous welded rail.

Insulated joints

Where track circuits exist for signalling purposes, insulated block joints are required. These compound the weaknesses of ordinary joints. Specially-made glued joints, where all the gaps are filled with epoxy resin, increase the strength again.

As an alternative to the insulated joint, audio frequency track circuits can be employed using a tuned loop formed in approximately 20 m (66 ft) of the rail as part of the blocking circuit. Some insulated joints are unavoidable within turnouts.

Another alternative is the axle counter, which can reduce the number of track circuits and thus the number of insulated rail joints required.

Continuous welded rail

Welded rail joint

A pull-apart on the Long Island Rail Road Babylon Branch being repaired by using flaming rope to expand the rail back to a point where it can be joined together

Most modern railways use continuous welded rail (CWR), sometimes referred to as ribbon rails. In this form of track, the rails are welded together by utilising flash butt welding to form one continuous rail that may be several kilometres long. Because there are few joints, this form of track is very strong, gives a smooth ride, and needs less maintenance; trains can travel on it at higher speeds and with less friction. Welded rails are more expensive to lay than jointed tracks, but have much lower maintenance costs. The first welded track was used in Germany in 1924 and the US in 1930[13] and has become common on main lines since the 1950s.

The preferred process of flash butt welding involves an automated track-laying machine running a strong electric current through the touching ends of two unjoined rails. The ends become white hot due to electrical resistance and are then pressed together forming a strong weld. Thermite welding is used to repair or splice together existing CWR segments. This is a manual process requiring a reaction crucible and form to contain the molten iron. Thermite-bonded joints are seen as less reliable and more prone to fracture or break.[citation needed]

North American practice is to weld 1⁄4 mile (400 m) long segments of rail at a rail facility and load it on a special train to carry it to the job site. This train is designed to carry many segments of rail which are placed so they can slide off their racks to the rear of the train and be attached to the ties (sleepers) in a continuous operation.[14]

If not restrained, rails would lengthen in hot weather and shrink in cold weather. To provide this restraint, the rail is prevented from moving in relation to the sleeper by use of clips or anchors. Attention needs to be paid to compacting the ballast effectively, including under, between, and at the ends of the sleepers, to prevent the sleepers from moving. Anchors are more common for wooden sleepers, whereas most concrete or steel sleepers are fastened to the rail by special clips that resist longitudinal movement of the rail. There is no theoretical limit to how long a welded rail can be. However, if longitudinal and lateral restraint are insufficient, the track could become distorted in hot weather and cause a derailment. Distortion due to heat expansion is known in North America as sun kink, and elsewhere as buckling. In extreme hot weather special inspections are required to monitor sections of track known to be problematic. In North American practice extreme temperature conditions will trigger slow orders to allow for crews to react to buckling or "sun kinks" if encountered.[15]

After new segments of rail are laid, or defective rails replaced (welded-in), the rails can be artificially stressed if the temperature of the rail during laying is cooler than what is desired. The stressing process involves either heating the rails, causing them to expand,[16] or stretching the rails with hydraulic equipment. They are then fastened (clipped) to the sleepers in their expanded form. This process ensures that the rail will not expand much further in subsequent hot weather. In cold weather the rails try to contract, but because they are firmly fastened, cannot do so. In effect, stressed rails are a bit like a piece of stretched elastic firmly fastened down.

CWR is laid (including fastening) at a temperature roughly midway between the extremes experienced at that location. (This is known as the "rail neutral temperature".) This installation procedure is intended to prevent tracks from buckling in summer heat or pulling apart in winter cold. In North America, because broken rails (known as a pull-apart) are typically detected by interruption of the current in the signaling system, they are seen as less of a potential hazard than undetected heat kinks.

An expansion joint on the Cornish Main Line, England

Joints are used in continuous welded rail when necessary, usually for signal circuit gaps. Instead of a joint that passes straight across the rail, the two rail ends are sometimes cut at an angle to give a smoother transition. In extreme cases, such as at the end of long bridges, a breather switch (referred to in North America and Britain as an expansion joint) gives a smooth path for the wheels while allowing the end of one rail to expand relative to the next rail.

Sleepers

A sleeper (tie) is a rectangular object on which the rails are supported and fixed. The sleeper has two main roles: to transfer the loads from the rails to the track ballast and the ground underneath, and to hold the rails to the correct width apart (to maintain the rail gauge). They are generally laid transversely to the rails.

Fixing rails to sleepers

Various methods exist for fixing the rail to the sleeper. Historically spikes gave way to cast iron chairs fixed to the sleeper, more recently springs (such as Pandrol clips) are used to fix the rail to the sleeper chair.

Portable track

Panama Canal construction track

Sometimes rail tracks are designed to be portable and moved from one place to another as required. During construction of the Panama Canal, tracks were moved around excavation works. These track gauge were 5 ft (1,524 mm) and the rolling stock full size. Portable tracks have often been used in open pit mines. In 1880 in New York City, sections of heavy portable track (along with much other improvised technology) helped in the epic move of the ancient obelisk in Central Park to its final location from the dock where it was unloaded from the cargo ship SS Dessoug.

Cane railways often had permanent tracks for the main lines, with portable tracks serving the canefields themselves. These tracks were narrow gauge (for example, 2 ft (610 mm)) and the portable track came in straights, curves, and turnouts, rather like on a model railway.[17]

Decauville was a source of many portable light rail tracks, also used for military purposes.

The permanent way is so called because temporary way tracks were often used in the construction of that permanent way.

Layout

The geometry of the tracks is three-dimensional by nature, but the standards that express the speed limits and other regulations in the areas of track gauge, alignment, elevation, curvature and track surface are usually expressed in two separate layouts for horizontal and vertical.

Horizontal layout is the track layout on the horizontal plane. This involves the layout of three main track types: tangent track (straight line), curved track, and track transition curve (also called transition spiral or spiral) which connects between a tangent and a curved track.

Vertical layout is the track layout on the vertical plane including the concepts such as crosslevel, cant and gradient.[18][19]

A sidetrack is a railroad track other than siding that is auxiliary to the main track. The word is also used as a verb (without object) to refer to the movement of trains and railcars from the main track to a siding, and in common parlance to refer to giving in to distractions apart from a main subject.[20] Sidetracks are used by railroads to order and organize the flow of rail traffic.

Gauge

Measuring rail gauge

During the early days of rail, there was considerable variation in the gauge used by different systems. Today, 54.8% of the world's railways use a gauge of 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in), known as standard or international gauge.[citation needed] Gauges wider than standard gauge are called broad gauge; narrower, narrow gauge. Some stretches of track are dual gauge, with three (or sometimes four) parallel rails in place of the usual two, to allow trains of two different gauges to use the same track.[21]

Gauge can safely vary over a range. For example, U.S. federal safety standards allow standard gauge to vary from 4 ft 8 in (1,420 mm) to 4 ft 9 1⁄2 in (1,460 mm) for operation up to 60 mph (97 km/h).

Maintenance

Circa 1917, American section gang (gandy dancers) responsible for maintenance of a particular section of railway. One man is holding a lining bar (gandy), while others are using rail tongs to position a rail.

Track needs regular maintenance to remain in good order, especially when high-speed trains are involved. Inadequate maintenance may lead to a "slow order" (North American terminology, or Temporary speed restriction in the United Kingdom) being imposed to avoid accidents (see Slow zone). Track maintenance was at one time hard manual labour, requiring teams of labourers, or trackmen (US: gandy dancers; UK: platelayers; Australia: fettlers), who used lining bars to correct irregularities in horizontal alignment (line) of the track, and tamping and jacks to correct vertical irregularities (surface). Currently, maintenance is facilitated by a variety of specialised machines.

Flange oilers lubricate wheel flanges to reduce rail wear in tight curves, Middelburg, Mpumalanga, South Africa

The surface of the head of each of the two rails can be maintained by using a railgrinder.

Common maintenance jobs include changing sleepers, lubricating and adjusting switches, tightening loose track components, and surfacing and lining track to keep straight sections straight and curves within maintenance limits. The process of sleeper and rail replacement can be automated by using a track renewal train.

Spraying ballast with herbicide to prevent weeds growing through and redistributing the ballast is typically done with a special weed killing train.

Over time, ballast is crushed or moved by the weight of trains passing over it, periodically requiring relevelling ("tamping") and eventually to be cleaned or replaced. If this is not done, the tracks may become uneven causing swaying, rough riding and possibly derailments. An alternative to tamping is to lift the rails and sleepers and reinsert the ballast beneath. For this, specialist "stoneblower" trains are used.

Rail inspections utilize nondestructive testing methods to detect internal flaws in the rails. This is done by using specially equipped HiRail trucks, inspection cars, or in some cases handheld inspection devices.

Rails must be replaced before the railhead profile wears to a degree that may trigger a derailment. Worn mainline rails usually have sufficient life remaining to be used on a branch line, siding or stub afterwards and are "cascaded" to those applications.

The environmental conditions along railroad track create a unique railway ecosystem. This is particularly so in the United Kingdom where steam locomotives are only used on special services and vegetation has not been trimmed back so thoroughly. This creates a fire risk in prolonged dry weather.

In the UK, the cess is used by track repair crews to walk to a work site, and as a safe place to stand when a train is passing. This helps when doing minor work, while needing to keep trains running, by not needing a Hi-railer or transport vehicle blocking the line to transport crew to get to the site.

Maintenance of way equipment in Italy

A track renewal train in Pennsylvania

Bed and foundation

Intercity-Express Track, Germany

On this Japanese high-speed line, mats have been added to stabilize the ballast

Railway tracks are generally laid on a bed of stone track ballast or track bed, in turn is supported by prepared earthworks known as the track formation. The formation comprises the subgrade and a layer of sand or stone dust (often sandwiched in impervious plastic), known as the blanket, which restricts the upward migration of wet clay or silt. There may also be layers of waterproof fabric to prevent water penetrating to the subgrade. The track and ballast form the permanent way. The term foundation may be used to refer to the ballast and formation, i.e. all man-made structures below the tracks.

Some railroads are using asphalt pavement below the ballast in order to keep dirt and moisture from moving into the ballast and spoiling it. The fresh asphalt also serves to stabilize the ballast so it won't move around so easily.[22]

Additional measures are required where the track is laid over permafrost, such as on the Qingzang Railway in Tibet. For example, transverse pipes through the subgrade allow cold air to penetrate the formation and prevent that subgrade from melting.

The sub-grade layers are slightly sloped to one side to help drainage of water. Rubber sheets may be inserted to help drainage and also protect iron bridgework from being affected by rust.

Historical development

The technology of rail tracks developed over a long period, starting with primitive timber rails in mines in the 17th century.

See also

- Degree of curvature

- Difference between train and tram rails

- Exothermic welding

Glossary of rail terminology

(including US/UK and other

regional/national differences)- Monorail

- Rack railway

Roll way, part of the track of a rubber-tyred metro[23]

- Rubber-tyred metro

- Street running

- TGV track construction

- Tramway (industrial)

References

^ Showing part of the track

^ Morris, Ellwood (1841), "On Cast Iron Rails for Railways", American Railroad Journal and Mechanic's Magazine, 13 (7 new series): 270–277, 298–304.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Hawkshaw, J. (1849). "Description of the Permanent Way, of the Lancashire and Yorkshire, the Manchester and Southport, and the Sheffield, Barnsley and Wakefield Railways". Minutes of the Proceedings. 8 (1849): 261. doi:10.1680/imotp.1849.24189.

^ Reynolds, J. (1838). "On the Principle and Construction of Railways of Continuous Bearing. (Including Plate)". ICE Transactions. 2: 73. doi:10.1680/itrcs.1838.24387.

^ "Eleventh Annual Report (1848)", Annual report[s] of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Rail Road Company, 4, pp. 17–20

^ 2.3.3 Design and Manufacture of Embedded Rail Slab Track Components (PDF), Innotrack, 12 June 2008

^ "Putting slab track to the test", www.railwaygazette.com, 1 October 2002

^ Esveld, Coenraad (2003), "Recent developments in slab track" (PDF), European Railway Review (2): 84–5

^ A Metallurgical History of Railmaking Slee, David E. Australian Railway History, February, 2004 pp43-56

^

Carolyn Fitzpatrick (2008-07-24). "Heavy haul in the high north". Railway Gazette. Archived from the original on 2009-05-01. Retrieved 2008-08-10.Premium steel rails will not be used, because the material has an increased potential to fracture at very low temperatures. Regular carbon steel is preferred, with a very high premium on the cleanliness of the steel. For this project, a low-alloy rail with standard strength and a Brinell hardness in the range of 300 would be most appropriate.

^ ""Snake heads" held up early traffic". Syracuse Herald-Journal. Syracuse, NY. March 20, 1939. p. 77 – via Newspapers.com.

^ "Snakeheads on antebellum railroads". Frederick Jackson Turner Overdrive. February 6, 2012.

^ C. P. Lonsdale (September 1999). "Thermite Rail Welding: History, Process Developments, Current Practices And Outlook For The 21st Century" (PDF). Proceedings of the AREMA 1999 Annual Conferences. The American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

^ http://conrailphotos.thecrhs.org/node/11104

^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300500772_Rail_Temperature_Approximation_and_Heat_Slow_Order_Best_Practices

^ "Continuous Welded Rail". Grandad Sez: Grandad's Railway Engineering Section. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

^ Narrow Gauge Down Under magazine, January 2010, p. 20.

^ PART 1025 Track Geometry (Issue 2 – 07/10/08 ed.). Department of Planning Transport, and Infrastructure - Government of South Australia. 2008.

^ Track Standards Manual - Section 8: Track Geometry (PDF). Railtrack PLC. December 1998. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

^ Dictionary.com

^ "message in the mailing list '1520mm' on Р75 rails".

^ http://www.engr.uky.edu/~jrose/papers/Hot%20Mix%20Asphalt%20Railway%20Trackbeds.pdf

^ runway (roll way)

Bibliography

- Pike, J., (2001), Track, Sutton Publishing,

ISBN 0-7509-2692-9

- Firuziaan, M. and Estorff, O., (2002), Simulation of the Dynamic Behavior of Bedding-Foundation-Soil in the Time Domain, Springer Verlag.

Robinson, A M (2009). Fatigue in railway infrastructure. Woodhead Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-85573-740-2.

Lewis, R (2009). Wheel/rail interface handbook. Woodhead Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84569-412-8.

External links

![]() Media related to Rail tracks at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rail tracks at Wikimedia Commons

- Table of North American tee rail (flat bottom) sections

- ThyssenKrupp handbook, Vignoles rail

- ThyssenKrupp handbook, Light Vignoles rail

- Track Details in photographs

- "Drawing of England Track Laying in Sections at 200 yards an hour" Popular Mechanics, December 1930

Winchester, Clarence, ed. (1936), "The permanent way", Railway Wonders of the World, pp. 331–338 illustrated description of the construction and maintenance of the railway- Railway technical