Buffalo, New York

| Buffalo, New York | |||

|---|---|---|---|

City | |||

City of Buffalo | |||

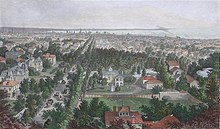

Left to right from top: Buffalo panorama, Canalside, KeyBank Center, County and City Hall, Buffalo Savings Bank, Peace Bridge, Buffalo City Hall | |||

| |||

Nickname(s): The City of Good Neighbors, The Queen City, The City of No Illusions, The Nickel City, Queen City of the Lakes, City of Light | |||

Location in Erie County and the state of New York | |||

Buffalo, New York Location in the United States | |||

Coordinates: 42°54′17″N 78°50′58″W / 42.90472°N 78.84944°W / 42.90472; -78.84944Coordinates: 42°54′17″N 78°50′58″W / 42.90472°N 78.84944°W / 42.90472; -78.84944 | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | New York | ||

| County | Erie | ||

| First settled (village) | 1789 | ||

| Founded | 1801 | ||

| Incorporated (city) | 1832 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Byron Brown (D) | ||

| • City Council | Buffalo Common Council | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 52.5 sq mi (136.0 km2) | ||

| • Land | 40.6 sq mi (105.2 km2) | ||

| • Water | 11.9 sq mi (30.8 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 600 ft (183 m) | ||

| Population (2010) | |||

| • City | 261,452 | ||

| • Estimate (2017)[1] | 258,612 | ||

| • Density | 6,436/sq mi (2,568/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 935,906 (US: 46th) | ||

| • Metro | 1,134,210 (US: 49th) | ||

| • CSA | 1,213,668 (US: 44th) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Buffalonian | ||

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) | ||

| ZIP code | 142XX | ||

| Area code(s) | 716 | ||

| FIPS code | 36-11000 | ||

GNIS feature ID | 0973345 | ||

| Website | www.city-buffalo.com | ||

Buffalo is the second largest city in the U.S. state of New York. As of July 2016[update], the population was 256,902. The city is the county seat of Erie County, and a major gateway for commerce and travel across the Canada–United States border, forming part of the bi-national Buffalo Niagara Region.

The Buffalo area was inhabited before the 17th century by the Native American Iroquois tribe and later by French settlers. The city grew significantly in the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of immigration, the construction of the Erie Canal and rail transportation, and its close proximity to Lake Erie. This growth provided an abundance of fresh water and an ample trade route to the Midwestern United States while grooming its economy for the grain, steel and automobile industries that dominated the city's economy in the 20th century. Since the city's economy relied heavily on manufacturing, deindustrialization in the latter half of the 20th century led to a steady decline in population. While some manufacturing activity remains, Buffalo's economy has transitioned to service industries with a greater emphasis on healthcare, research and higher education, which emerged following the Great Recession.

Buffalo is on the eastern shore of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, 16 miles south of Niagara Falls. Its early embrace of electric power led to the nickname "The City of Light". The city is also famous for its urban planning and layout by Joseph Ellicott, an extensive system of parks designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, as well as significant architectural works. Its culture blends Northeastern and Midwestern traditions, with annual festivals including Taste of Buffalo and Allentown Art Festival, two professional sports teams (Buffalo Bills and Buffalo Sabres), and a music and arts scene.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 History

2.1 Prehistory and European exploration

2.2 Founding, Erie Canal, and railroads

2.3 Rise of heavy industry, decline, urban renewal

2.4 Recent development

3 Geography

3.1 Cityscape

3.1.1 Architecture

3.1.2 Neighborhoods

3.2 Climate

4 Demographics

5 Economy

6 Crime

7 Culture

7.1 Cuisine

7.2 Fine and performing arts

7.3 Music

7.4 Tourism

8 Sports

9 Parks and recreation

10 Government

11 Education

12 Infrastructure

12.1 Healthcare

12.2 Transportation

12.3 Utilities

13 Media

14 Notable people

15 Sister cities

16 See also

17 Notes and references

17.1 Notes

17.2 References

17.3 Bibliography

18 Further reading

19 External links

Etymology

The city of Buffalo received its name from a nearby creek called Buffalo Creek.[2] British military engineer Captain John Montresor made reference to "Buffalo Creek" in his 1764 journal, which may be the earliest recorded appearance of the name.[3]

There are several theories regarding how Buffalo Creek received its name.[4][5][6] While it is possible its name originated from French fur traders and Native Americans calling the creek Beau Fleuve (French for "Beautiful River"),[4][5] it is also possible Buffalo Creek was named after the American buffalo, whose historical range may have extended into western New York.[6][7][8]

History

Prehistory and European exploration

An early map of the village of Buffalo and outer lots in 1854. Inset is Ellicott's 1804 plan.

The village of Buffalo in 1813.

Walk-on-the-Water was the first steamboat to sail Lake Erie in 1818

The first inhabitants of the State of New York are believed to have been nomadic Paleo-Indians, who migrated after the disappearance of Pleistocene glaciers during or before 7000 BCE.[9]

Around 1000 CE, 1,000 years ago, the Woodland period began, marked by the rise of the Iroquois Confederacy and its tribes throughout the state.[9]

During French exploration of the region in 1620, the region was occupied simultaneously by the agrarian Erie people, a tribe outside of the Five Nations of the Iroquois southwest of Buffalo Creek,[10] and the Wenro people or Wenrohronon, an Iroquoian-speaking tribal offshoot of the large Neutral Nation who lived along the inland south shore of Lake Ontario and at the east end of Lake Erie and a bit of its northern shore.[11] For trading, the Neutral people made a living by growing tobacco and hemp to trade with the Iroquois,[12] utilizing animal paths or warpaths to travel and move goods across the state. These paths were later paved, and now function as major roads.[13]

Later, during the Beaver Wars of the 1640s-1650s, the combined warriors of the Five Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy conquered the populous Neutrals[14] and their peninsular territory,[14] while the Senecas alone took out the Wenro and their territory, c. 1651[14][15][16]–1653.[a] Soon after, the Erie nation and territory was also destroyed by the Iroquois[17] over their assistance to Huron people during the Beaver Wars.[18]

It was Louis Hennepin and Sieur de La Salle who made the earliest European discoveries of the upper Niagara and Ontario regions in the late 1600s.[19] On August 7, 1679, La Salle launched a vessel, Le Griffon, that became the first full-sized ship to sail across the Great Lakes, eventually disappearing in Green Bay, Wisconsin.[20]

After the American Revolution, the colony of New York—now a state—began westward expansion, looking for habitable land by following trends of the Iroquois.[21] Land near fresh water was of considerable importance.[22] New York and Massachusetts were fighting for the territory Buffalo lies on, and Massachusetts had the right to purchase all but a one-mile (1600-meter) wide portion of land. The rights to the Massachusetts' territories were sold to Robert Morris in 1791, and two years later to the Holland Land Company.[23][24]

As a result of the war, in which the Iroquois tribe sided with the British Army,[25] Iroquois territory was gradually whittled away in the mid-to-late-1700s by white settlers through successive treaties statewide, such as the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784), the First Treaty of Buffalo Creek (1788), and the Treaty of Geneseo (1797). The Iroquois were corralled onto reservations, including Buffalo Creek. By the end of the 18th century, only 338 square miles (216,000 acres; 880 km2; 88,000 ha) of reservation territory remained.[26]

Founding, Erie Canal, and railroads

Buffalo harbour from the foot of Porter Avenue, 1871

1872 engraving of Buffalo

Early view of Buffalo's harbour

Early settlers along the mouth of Buffalo Creek were former slave Joseph "Black Joe" Hodges,[27][28] and Cornelius Winney, a Dutch trader from Albany who arrived in 1789.[29] The first white settlers along the creek were prisoners captured during the Revolutionary War.[30] The first resident and landowner[31] of Buffalo with a permanent presence was Captain William Johnston, a white Iroquois interpreter who had been present in the area since the days after the Revolutionary War and was granted creekside land by the Senecas as a gift of appreciation. His house was built at present-day Washington and Seneca streets.[32]

On July 20, 1793, the Holland Land Purchase was completed, containing the land of present-day Buffalo, brokered by Dutch investors from Holland.[33] The Treaty of Big Tree removed Iroquois title to lands west of the Genesee River in 1797.[34] In the fall of 1797, Joseph Ellicott, the architect who helped survey Washington D.C. with brother Andrew,[35][36] was appointed as the Chief of Survey for the Holland Land Company.[37] Over the next year, he began surveying the tract of land at the mouth of Buffalo Creek. This was completed in 1803,[38] and the new village boundaries extended from the creekside in the south to present-day Chippewa Street in the north and Carolina Street to the west,[39] which is where most settlers remained for the first decade of the 19th century.[citation needed] Although the company named the settlement "New Amsterdam," the name did not catch on, reverting to Buffalo within ten years.[40][39] Buffalo had the first road to Pennsylvania built in 1802 for migrants passing through to the Connecticut Western Reserve in Ohio.[41]

In 1804, Ellicott designed a radial grid plan that would branch out from the village forming bicycle-like spokes, interrupted by diagonals, similar to the system used in the nation's capital.[42] In the middle of the village was the intersection of eight streets, in what would become Niagara Square. Several blocks to the southeast he designed a semicircle fronting Main Street with an elongated park green, formerly his estate.[43][44] This would be known as Shelton Square,[45] at that time the center of the city (which would be dramatically altered in the mid-20th century),[46] with the intersecting streets bearing the names of Dutch Holland Land Company members,[47][b] today Erie, Church and Niagara streets.[43]Lafayette Square also lies one block to the north, which was then bounded by streets bearing Iroquois names.[38]

According to an early resident, in 1806 there were sixteen residences, a schoolhouse and two stores in the village, primarily near Main, Swan and Seneca streets.[48] There were also blacksmith shops, a tavern and a drugstore.[49] The streets were small at 40 feet wide, and the village was still surrounded by woods.[50] The first lot sold by the Holland Land Company was on September 11, 1806, to Zerah Phelps.[51] By 1808, lots would sell from $25 to $50.[52]

In 1804, Buffalo's population was estimated at 400, similar to Batavia, but Erie County's growth was behind Chautauqua, Genesee and Wyoming counties.[53] Neighboring village Black Rock to the northwest (today a Buffalo neighbourhood) was also an important centre.[43] Horatio J. Spafford noted in A Gazetteer of the State of New York that in fact, despite the growth the village of Buffalo had, Black Rock "is deemed a better trading site for a great trading town than that of Buffalo," especially when considering the regional profile of mundane roads extending eastward.[53] Before the east-to-west turnpike[further explanation needed] was completed, travelling from Albany to Buffalo would take a week,[54] while even a trip from nearby Williamsville to Batavia could take upwards of three days.[55][c]

Sketch of Buffalo, 1880

Although slavery was rare in the state, limited instances of slavery had taken place in Buffalo during the early part of the 19th century. General Peter Buell Porter is said to have had five slaves during his time in Black Rock, and several news ads also advertised slaves for sale.[56]

In 1810, a courthouse was built. By 1811, the population was 500, with many people farming or doing manual labor.[57] The first newspaper to be published was the Buffalo Gazette in October that same year.[52]

Fears of a second British war were stoked in 1812, when on June 27 a small craft carrying salt was captured by two boats on the Niagara River.[58] There were several skirmishes on the water in the following months.[59] On December 18, 1813, Fort Niagara was overrun with ease by 500 British troops and Native American soldiers.[which?] Soon after, General Amos Hall[60] ordered two thousand unskilled and drafted troops to march from Batavia to Buffalo, arriving December 26.[61] After the British crossed the Niagara River the night before December 30,[62] Buffalo and the village of Black Rock were burned in a frenzy the next in the Battle of Buffalo.[63][64] The battle and subsequent fire was in response to the unprovoked destruction of Niagara-on-the-Lake, then known as "Newark," by American forces.[65][66] While many residents were warned to leave,[62] those that did not escape were tomahawked and scalped in the ensuing battle.[67][60] Though only three buildings remained in the village, rebuilding was swift, finishing in 1815.[62][68]

Until April 2, 1821, the village of Buffalo was part of and the seat of Niagara County, until the legislature passed an act separating the two.[69]

On October 26, 1825,[70] the Erie Canal was completed, formed from part of Buffalo Creek,[71] with Buffalo a port-of-call for settlers heading westward.[72] At the time, the population was about 2,400.[73] By 1826, the 130 sq. mile Buffalo Creek Reservation at the western border of the village was transferred to Buffalo.[26] The Erie Canal brought about a surge in population and commerce, which led Buffalo to incorporate as a city in 1832.[74] The canal area was mature by 1847, with passenger and cargo ship activity leading to congestion in the harbor.[75]

Buffalo City Hall under construction, 1930

Assassination of William McKinley at the Temple of Music, 1901

The mid-1800s saw a boom in population, with the city doubling in size from 1845 to 1855.[76] Almost two-thirds of the city's population were foreign-born immigrants in 1855, predominately a mix of unskilled or educated Irish and Germans Catholics, who began self-segregating in different parts of the city. The Irish immigrants planted their roots along the railroad-heavy Buffalo River and Erie Canal to the southeast, to which there is still a heavy presence today; German immigrants found their way to the East Side, living a more laid-back, residential life.[77] Some immigrants were apprehensive about the change of environment and elected to leave the city for the western region, while others tried to stay behind in the hopes of expanding their native cultures.[78]

Fugitive black slaves began making their way northward to Buffalo in the 1840s, and also settled on the city's East Side.[79] In 1845, construction began on the Macedonia Baptist Church, a meeting spot in the Michigan and William Street neighborhood where blacks first settled.[80] It also functioned as an important meeting place for the abolitionist movement.[better source needed] Buffalo was a terminus point of the Underground Railroad with many fugitive slaves crossing the Niagara River to Fort Erie, Ontario in search of freedom.[81]

During the 1840s, Buffalo's port continued to develop. Both passenger and commercial traffic expanded with some 93,000 passengers heading west from the port of Buffalo.[82][better source needed] Grain and commercial goods shipments led to repeated expansion of the harbor.[citation needed] In 1843, the world's first steam-powered grain elevator was constructed by local merchant Joseph Dart and engineer Robert Dunbar.[83] "Dart's Elevator" enabled faster unloading of lake freighters along with the transshipment of grain in bulk from barges, canal boats, and rail cars.[84] By 1850, the city's population was 81,000.[74]

In 1860, there were a plethora of railway companies and lines crossing through and terminating in Buffalo. Major ones were the Buffalo, Bradford and Pittsburgh Railroad (1859), Buffalo and Erie Railroad and the New York Central Railroad (1853).[85] During this time, a quarter of all shipping traffic on Lake Erie was controlled by Buffalo citizens, and shipbuilding was a thriving industry for the city.[86]

Later, the Lehigh Valley Railroad would have its line terminate at Buffalo in 1867.

Rise of heavy industry, decline, urban renewal

Downtown Buffalo in 1945

Workers unload wheat into an elevator along the Buffalo River in 1900

Sprawling steel plant at Republic Steel in South Buffalo, 1973

At the dawn of the 20th century, local mills were among the first to benefit from hydroelectric power generated by the Niagara River. The city got the nickname City of Light at this time due to the widespread electric lighting.[87] It was also part of the automobile revolution, hosting the brass era car builders Pierce Arrow and the Seven Little Buffaloes early in the century.[88] At the same time, an exit of local entrepreneurs and industrial titans brought about a nascent stage that would see the city lose its competitiveness against Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Detroit.[89]

President William McKinley was shot and mortally wounded by an anarchist at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo on September 6, 1901.[90] McKinley died in the city eight days later[91] and Theodore Roosevelt was sworn in at the Wilcox Mansion.[91] The Great Depression of 1929–39 saw severe unemployment, especially among working-class men. The New Deal relief programs operated full force. The city became a stronghold of labor unions and the Democratic Party.[92]

During World War II, Buffalo saw the return of prosperity and full employment due to its position as a manufacturing center.[93][94] As one of the most populous cities of the 1950s, Buffalo's economy revolved almost entirely on its manufacturing base. Major companies such as Republic Steel and Lackawanna Steel employed tens of thousands of Buffalonians. Integrated national shipping routes would use the Soo Locks near Lake Superior and a vast network of railroads and yards that crossed the city.

Lobbying by local businesses and interest groups against the St. Lawrence Seaway began in the 1920s, long before its construction in 1957, which cut the city off from valuable trade routes. Its approval was reinforced by legislation shortly before its construction.[95] Shipbuilding in Buffalo, such as that of the American Ship Building Company, shut down in 1962, ending an industry that had been a sector of the city's economy since 1812, and a direct result of reduced waterfront activity.[96] With deindustrialization, and the nationwide trend of suburbanization; the city's economy began to deteriorate.[97][98] Like much of the Rust Belt, Buffalo, home to more than half a million people in the 1950s, has seen its population decline as heavy industries shut down and people left for the suburbs or other cities.[97][98][99]

Recent development

Like other Rust Belt cities such as Pittsburgh and Cleveland, Buffalo has attempted to revitalize its beleaguered economy and crumbling infrastructure. The trend of back offices opening in the area began in the 1980s.[100]

Geography

Buffalo is on Lake Erie's eastern end, opposite Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada.[101] It is located at the origin of the Niagara River, which flows northward over Niagara Falls and into Lake Ontario.[102] The city is 50 miles (80 km) south-southeast from Toronto. Relative to downtown, the city is generally flat with the exception of area surrounding North and High streets, where a hill of 90 feet gradually develops approaching from the south and north. In the Southtowns are the Boston Hills, while the Appalachian Mountains sit in the Southern Tier below them. To the north and east, the region maintains a flatter profile descending to Lake Ontario. Various types of shale, limestone and lagerstätten are prevalent in the geographic makeup of Buffalo and surrounding areas, which line the waterbeds within and bordering the city.[103]

Although there have not been any recent or significant earthquakes, Buffalo sits atop of the Southern Great Lakes Seismic Zone, which is part of the Great Lakes tectonic zone.[104]

Buffalo has four channels that flow through its boundaries: the Niagara River, Buffalo River and Creek, Scajaquada Creek, and the Black Rock Canal, which is adjacent to the Niagara River.[105]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 52.5 square miles (136 km2), of which 40.6 square miles (105 km2) is land and the rest water. The total area is 22.66% water.

Cityscape

Architecture

Elmwood Village

2001 image of the Niagara Peninsula, Niagara Falls and Buffalo from NASA's Terra satellite

Buffalo's architecture is diverse, with a collection of buildings from the 19th and 20th centuries.[106] Most structures and works are still standing, such as the country's largest intact parks system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux.[107][108] At the end of the 19th century, the Guaranty Building—constructed by Louis Sullivan—was a prominent example of an early high-rise skyscraper.[109][110] The 20th century saw works such as the Art Deco-style Buffalo City Hall and Buffalo Central Terminal, Electric Tower, the Richardson Olmsted Complex, and the Rand Building. Urban renewal from the 1950s–1970s gave way to the construction of the Brutalist-style Buffalo City Court Building and One Seneca Tower—formerly the HSBC Center, the city's tallest building.[111]

Neighborhoods

Climate

| Buffalo, New York | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Buffalo has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb bordering on Dfa), which is common in the Great Lakes region.[112][113] Buffalo has snowy winters, but it is rarely the snowiest city in New York state.[114][115] The Blizzard of 1977 resulted from a combination of high winds and snow previously accumulated on land and on frozen Lake Erie.[116] Snow does not typically impair the city's operation, but can cause significant damage during the autumn as with the October 2006 storm.[117][118] In November 2014, the region had a record-breaking storm, producing over 5 1⁄2 feet (66 inches; 170 centimetres) of snow, this storm was named "Snowvember".[119] Buffalo has the sunniest and driest summers of any major city in the Northeast, but still has enough rain to keep vegetation green and lush.[113] Summers are marked by plentiful sunshine and moderate humidity and temperature.[113] Obscured by the notoriety of Buffalo's winter snow is the fact Buffalo benefits from other lake effects such as the cooling southwest breezes off Lake Erie in summer that gently temper the warmest days.[113] As a result, temperatures only rise above 90 °F (32.2 °C) three times in the average year,[113] and the Buffalo station of the National Weather Service has never recorded an official temperature of 100 °F (37.8 °C) or more.[120] Rainfall is moderate but typically occurs at night. Lake Erie's stabilizing effect continues to inhibit thunderstorms and enhance sunshine in the immediate Buffalo area through most of July.[113] August usually has more showers and is hotter and more humid as the warmer lake loses its temperature-stabilizing influence.[113] The highest recorded temperature in Buffalo was 99 °F (37 °C) on August 27, 1948[121] and the lowest recorded temperature was −20 °F (−29 °C), which occurred twice, on February 9, 1934 and February 2, 1961.[122]

| Climate data for Buffalo Niagara International Airport, New York (1981–2010 normals,[d] extremes 1871–present[e]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) | 71 (22) | 82 (28) | 94 (34) | 94 (34) | 97 (36) | 97 (36) | 99 (37) | 98 (37) | 92 (33) | 80 (27) | 74 (23) | 99 (37) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 54.4 (12.4) | 54.9 (12.7) | 68.8 (20.4) | 79.0 (26.1) | 82.9 (28.3) | 88.4 (31.3) | 89.2 (31.8) | 88.2 (31.2) | 85.2 (29.6) | 76.6 (24.8) | 67.5 (19.7) | 55.6 (13.1) | 90.9 (32.7) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) | 33.3 (0.7) | 42.0 (5.6) | 55.0 (12.8) | 66.5 (19.2) | 75.3 (24.1) | 79.9 (26.6) | 78.4 (25.8) | 71.1 (21.7) | 59.0 (15) | 47.6 (8.7) | 36.1 (2.3) | 56.4 (13.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 18.5 (−7.5) | 19.2 (−7.1) | 26.0 (−3.3) | 36.8 (2.7) | 47.4 (8.6) | 57.3 (14.1) | 62.3 (16.8) | 60.8 (16) | 53.4 (11.9) | 42.7 (5.9) | 33.9 (1.1) | 24.1 (−4.4) | 40.3 (4.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −0.5 (−18.1) | 1.8 (−16.8) | 7.8 (−13.4) | 24.2 (−4.3) | 34.8 (1.6) | 44.7 (7.1) | 51.4 (10.8) | 49.2 (9.6) | 39.8 (4.3) | 29.8 (−1.2) | 20.3 (−6.5) | 5.3 (−14.8) | −3.7 (−19.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −16 (−27) | −20 (−29) | −7 (−22) | 5 (−15) | 25 (−4) | 35 (2) | 43 (6) | 38 (3) | 32 (0) | 20 (−7) | 2 (−17) | −10 (−23) | −20 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.18 (80.8) | 2.49 (63.2) | 2.87 (72.9) | 3.01 (76.5) | 3.46 (87.9) | 3.66 (93) | 3.23 (82) | 3.26 (82.8) | 3.90 (99.1) | 3.52 (89.4) | 4.01 (101.9) | 3.89 (98.8) | 40.48 (1,028.2) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 25.3 (64.3) | 17.3 (43.9) | 12.9 (32.8) | 2.7 (6.9) | 0.3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.9 (2.3) | 7.9 (20.1) | 27.4 (69.6) | 94.7 (240.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 19.2 | 16.0 | 15.1 | 13.1 | 12.7 | 12.1 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 15.0 | 18.3 | 166.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 16.3 | 13.1 | 9.2 | 3.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 4.9 | 14.0 | 61.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76.0 | 75.9 | 73.3 | 67.8 | 67.2 | 68.6 | 68.1 | 72.1 | 74.0 | 72.9 | 75.8 | 77.6 | 72.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 91.3 | 108.0 | 163.7 | 204.7 | 258.3 | 287.1 | 306.7 | 266.4 | 207.6 | 159.4 | 84.4 | 69.0 | 2,206.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 31 | 37 | 44 | 51 | 57 | 63 | 66 | 62 | 55 | 47 | 29 | 25 | 49 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[123][124][125] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 1,508 | — | |

| 1820 | 2,095 | 38.9% | |

| 1830 | 8,668 | 313.7% | |

| 1840 | 18,213 | 110.1% | |

| 1850 | 42,261 | 132.0% | |

| 1860 | 81,129 | 92.0% | |

| 1870 | 117,714 | 45.1% | |

| 1880 | 155,134 | 31.8% | |

| 1890 | 255,664 | 64.8% | |

| 1900 | 352,387 | 37.8% | |

| 1910 | 423,715 | 20.2% | |

| 1920 | 506,775 | 19.6% | |

| 1930 | 573,076 | 13.1% | |

| 1940 | 575,901 | 0.5% | |

| 1950 | 580,132 | 0.7% | |

| 1960 | 532,759 | −8.2% | |

| 1970 | 462,768 | −13.1% | |

| 1980 | 357,870 | −22.7% | |

| 1990 | 328,123 | −8.3% | |

| 2000 | 292,648 | −10.8% | |

| 2010 | 261,310 | −10.7% | |

| Est. 2017 | 258,612 | [1] | −1.0% |

| Historical Population Figures[126] U.S. Decennial Census[127] 2013 Estimate[128] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[129] | 1990[130] | 1970[130] | 1940[130] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 50.4% | 64.7% | 78.7% | 96.8% |

| Black or African American | 38.6% | 30.7% | 20.4% | 3.1% |

Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 10.5% | 4.9% | 1.6%[131] | (X) |

| Asian | 3.2% | 1.0% | 0.2% | − |

Like most former industrial cities of the Great Lakes region in the United States, Buffalo is recovering from an economic depression from suburbanization and the loss of its industrial base. The city's population peaked in 1950 when it was the 15th largest city in the United States, and its population has been spreading out to the suburbs every census since then.

At the 2010 Census, the city's population was 50.4% White (45.8% non-Hispanic White alone), 38.6% Black or African-American, 0.8% American Indian and Alaska Native, 3.2% Asian, 3.9% from some other race and 3.1% from two or more races. 10.5% of the total population was Hispanic or Latino of any race.[132] Since 2003, there has been an ever-growing number of Burmese refugees, mostly of the Karen ethnicity, with an estimated 4,665 now residing in Buffalo.[133]

The median income for a household in the city is $24,536 and the median income for a family is $30,614. Males have a median income of $30,938 versus $23,982 for females. The per capita income for the city is $14,991. 26.6% of the population and 23% of families are below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 38.4% of those under the age of 18 and 14% of those 65 and older are living below the poverty line.

Economy

Electric Tower, 2010

One M&T Plaza, headquarters of M&T Bank

Buffalo's economic sectors include industrial, light manufacturing, high technology and services.[citation needed] The State of New York, with over 15,000 employees, is the city's largest employer.[134] Other major employers include the United States government, Kaleida Health, M&T Bank (which is headquartered in Buffalo), the University at Buffalo, General Motors, Time Warner Cable and Tops Friendly Markets.[citation needed] Buffalo is home to Rich Products, Canadian brewer Labatt, cheese company Sorrento Lactalis, Delaware North Companies[135] and New Era Cap Company. More recently, the Tesla Gigafactory 2 opened in South Buffalo in summer 2017, as a result of the Buffalo Billion program.

The loss of traditional jobs in manufacturing, rapid suburbanization and high labor costs have led to economic decline and made Buffalo one of the poorest U.S. cities with populations of more than 250,000 people. An estimated 28.7–29.9% of Buffalo residents live below the poverty line, behind either only Detroit,[136] or only Detroit and Cleveland.[137] Buffalo's median household income of $27,850 is third-lowest among large cities, behind only Miami and Cleveland; however the metropolitan area's median household income is $57,000.[138] This, in part, has led to the Buffalo-Niagara Falls metropolitan area having the most affordable housing market in the U.S. The quarterly NAHB/Wells Fargo Housing Opportunity Index (HOI) noted nearly 90% of the new and existing homes sold in the metropolitan area during the second quarter were affordable to families making the area's median income of $57,000.[citation needed] As of 2014[update], the median home price in the city was $95,000.[139]

Buffalo's economy has begun to see significant improvements since the early 2010s.[140] Money from New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo through a program known locally as "Buffalo Billion" has brought new construction, increased economic development, and hundreds of new jobs to the area.[141] As of March 2015, Buffalo's unemployment rate was 5.9%,[142] slightly above the national average of 5.5%.[143] In 2016, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis valued the Buffalo area's economy at $54.9 billion.[144]

Crime

Buffalo's crime rate is much higher than the national average. In 2015, there were 41 murders, 1,033 robberies, and 1,640 assaults.[145] In 2016, bizjournals.com published an article including an FBI report that ranked Buffalo's violent crime rate as the 15th-worst in the nation.[146]

Culture

Buffalo wings served with celery

Cuisine

Buffalo's cuisine encompasses a variety of cultural contributions, including Italian, Irish, Jewish, German, Polish, African-American, Greek, and American influences. In 2015, the National Geographic Society ranked Buffalo third on their list of "The World's Top Ten Food Cities".[147] Locally owned restaurants offer Chinese, German, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Thai, Mexican, Italian, Arab, Indian, Myanmar, Caribbean, soul food, and French cuisine.[148][149] Buffalo's local pizzerias differ from the thin-crust New York-style pizzerias and deep-dish Chicago-style pizzerias, and is locally known for being a midpoint between the two.[150] The Beef on weck sandwich, kielbasa, sponge candy, pastry hearts, pierogi and haddock fish fries are local favorites, as is a loganberry-flavored beverage that remains relatively obscure outside of Western New York and Southern Ontario.[151]Teressa Bellissimo first prepared the now widespread Chicken Wings at the Anchor Bar in 1964.[152]

Buffalo has several well-known food companies. Non-dairy whipped topping was invented in Buffalo in 1945 by Robert E. Rich, Sr.[153] His company, Rich Products, is one of the city's largest private employers.[154]General Mills was organized in Buffalo, and Gold Medal brand flour, Wheaties, Cheerios and other General Mills brand cereals are manufactured here. Archer Daniels Midland operates its largest flour mill in the city.[155] Buffalo is home to one of the world's largest privately held food companies, Delaware North Companies, which operates concessions in sports arenas, stadiums, resorts and many state and federal parks.[156]

The Taste of Buffalo and National Buffalo Wing Festival showcase food from the Buffalo area. These are two of the many festivals that occur in Buffalo during the summer.

Fine and performing arts

The Albright–Knox Art Gallery

Buffalo is home to over 50 private and public art galleries,[157] most notably the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, home to a collection of modern and contemporary art, and the Burchfield-Penney Art Center.[158] In 2012, AmericanStyle ranked Buffalo twenty-fifth in its list of top mid-sized cities for art.[159] It is also home to many independent media and literary arts organizations like Squeaky Wheel Film and Media Arts Center. The Buffalo area's largest theater is Shea's Performing Arts Center, designed to accommodate 4,000 people with interiors by Louis Comfort Tiffany. Built in 1926, the theater presents Broadway musicals and concerts.[160] The theater community in the Buffalo Theater District includes over 20 professional companies.[161][162][163]

The Allentown Art Festival showcases local and national artists every summer, in Buffalo's Allentown district.

Music

Kleinhans Music Hall is home to the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra.

The Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, which performs at Kleinhans Music Hall, is one of the city's most prominent performing arts institutions. During the 1960s and 1970s, under the musical leadership of Lukas Foss and Michael Tilson Thomas, the Philharmonic collaborated with Grateful Dead and toured with the Boston Pops Orchestra.[164]

Buffalo has the roots of many jazz and classical musicians, and it is also the founding city for several mainstream bands and musicians, including Rick James, Billy Sheehan, The Quakes, and The Goo Goo Dolls. Vincent Gallo, a Buffalo-born filmmaker and musician, played in several local bands.[citation needed]Jazz fusion band Spyro Gyra and jazz saxophonists Grover Washington Jr. also got their starts in Buffalo.[citation needed] Pianist and composer Leonard Pennario was born in Buffalo in 1924 and made his debut concert at Carnegie Hall in 1943.[citation needed] Buffalo's "Colored Musicians Club", an extension of what was long ago a separate musicians' union local, is thriving today and maintains a significant jazz history within its walls. Well-known indie artist Ani DiFranco hails from Buffalo.[citation needed]

Tourism

Although the region's primary tourism destination is Niagara Falls to the north, Buffalo's tourism relies on historical attractions and outdoor recreation. The city's points of interest include the Edward M. Cotter fireboat, considered the world's oldest active fireboat[165] and is a United States National Historic Landmark, Buffalo and Erie County Botanical Gardens, the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society,[166]Buffalo Museum of Science,[167] the Buffalo Zoo—the third oldest in the United States—[168]Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo and Erie County Naval & Military Park, the Anchor Bar and Darwin D. Martin House.

The site of the former Erie Canal Harbor, Canalside has become a popular destination for tourists and residents since 2007 when Buffalo and the New York Power Authority began to redevelop the former site of the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium into historically accurate canals.

Buffalo is one of the largest Polish-American centres in the United States. As a result, many aspects of Polish culture have found a home in the city from food to festivals. One of the best examples is the yearly celebration of Easter Monday, known to many Eastern Europeans as Dyngus Day.[169]

Sports

A cameraman shoots a game at New Era Field.

Buffalo and the surrounding region is home to two major leagues professional sports teams. The NHL's Buffalo Sabres play in the city of Buffalo, while the NFL's Buffalo Bills play in suburban Orchard Park, New York, where they have been since 1973.

The Bills, established in 1959, played in War Memorial Stadium until 1973, when Rich Stadium, now New Era Field, opened. The team competes in the AFC East division. Since the AFL–NFL merger in 1970, the Bills have won the AFC conference championship four consecutive times (1990, 1991, 1992, 1993), resulting in four lost Super Bowls (Super Bowl XXV, Super Bowl XXVI, Super Bowl XXVII and Super Bowl XXVIII); they were the only NFL team without a playoff appearance in the 21st century from 2011 until 2017, having missed the playoffs each season since 2000.

The Sabres, established in 1970, played in Buffalo Memorial Auditorium until 1996, when Marine Midland Arena, now KeyBank Center opened. The team is within the Atlantic Division of the NHL. The team has won one Presidents' Trophy (2006-2007) and three conference championships (1974-1975, 1979-1980 and 1998-1999). However, like the Bills, the Sabres don't have a league championship, having lost the 1975 Stanley Cup to the Philadelphia Flyers and the 1999 Stanley Cup to the Dallas Stars. Since 2014, both the Bills and Sabres have been owned by Terrence Pegula, a key investor in Buffalo's revitalization efforts.

The Buffalo Braves played at the National Basketball Association from 1970 to 1978, with their home games held at the Buffalo Memorial Auditorium. The team struggled financially, so it was relocated to California and became the San Diego Clippers.

Buffalo is also home to several minor sports teams, including the Buffalo Bisons (baseball; an affiliate of the MLB's Toronto Blue Jays since 2014), FC Buffalo (soccer) as well as a professional women's team, the Buffalo Beauts (hockey). The Buffalo Bandits indoor lacrosse team was established in 1992 and played their home games in Buffalo Memorial Auditorium until 1996 when they followed the Sabres to Marine Midland Arena. They have won eight division championships and four league championships (1991-1992, 1992-1993, 1995-1996 and 2007-2008). The Buffalo Bulls are a Division I college team representing the State University of New York at Buffalo (which no longer is in the city proper); the only Division I college sports program within city limits is the Canisius Golden Griffins.

| Sport | League | Club | Founded | Venue | Titles | Championship years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Football | NFL | Buffalo Bills | 1960 | New Era Field[170] | 2 | 1964*, 1965* |

Hockey | NHL | Buffalo Sabres | 1970 | KeyBank Center | 0 | |

Baseball | IL | Buffalo Bisons | 1979† | Sahlen Field | 3 | 1997, 1998, 2004 |

Lacrosse | NLL | Buffalo Bandits | 1992 | KeyBank Center | 4 | 1992, 1993, 1996, 2008 |

Soccer | NPSL | FC Buffalo | 2009 | All-High Stadium | 0 | |

Hockey | NWHL | Buffalo Beauts | 2015 | HarborCenter | 1 | 2017 |

*

American Football League (AFL) championships were earned prior to the NFL merging with the AFL in 1970.

† Date refers to current incarnation; Buffalo Bisons previously operated from the 1870s until 1970 and the current Bisons count this team as part of their history.

Parks and recreation

View of Canalside and Buffalo Naval Park

Hoyt Lake at Delaware Park

The Buffalo parks system has over 20 parks with several parks accessible from any part of the city. The Olmsted Park and Parkway System is the hallmark of Buffalo's many green spaces. Three-fourths of city parkland is part of the system, which comprises six major parks, eight connecting parkways, nine circles and seven smaller spaces. Constructed in 1868 by Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux, the system was integrated into the city and marks the first attempt in America to lay out a coordinated system of public parks and parkways. The Olmsted-designed portions of the Buffalo park system are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and are maintained by the Buffalo Olmsted Parks Conservancy (BOPC), a non-profit, for public benefit corporation which serves as the city's parks department. It is the first non-governmental organization of its kind to serve in such a capacity in the United States.[171]

Situated at the confluence of Lake Erie and the Buffalo and Niagara rivers, Buffalo is a waterfront city. The city's rise to economic power came through its waterways in the form of transshipment, manufacturing, and an endless source of energy. Buffalo's waterfront remains, though to a lesser degree, a hub of commerce, trade and industry. Beginning in 2009, a significant portion of Buffalo's waterfront began to be transformed into a focal point for social and recreational activity. To this end, Buffalo Harbor State Park, nicknamed "Outer Harbor," was opened in 2014.[172] Buffalo's intent was to stress its architectural and historical heritage to create a tourism destination, and early data indicates they were successful.[173]

Government

Robert H. Jackson United States Courthouse

At the municipal level, the City of Buffalo has a mayor and a council of nine councilmembers. Buffalo also serves as the seat of Erie County with some of the 11 members of county legislature representing at least a portion of Buffalo. At the state level, there are three states assemblymembers and two state senators representing parts of the city proper. At the federal level, Buffalo is the heart of New York's 26th congressional district in the House of Representatives, represented by Democrat Brian Higgins.

Buffalo City Hall, with McKinley Monument in the foreground

In a trend common to northern "Rust Belt" regions, the Democratic Party has dominated Buffalo's political life for the last half-century. The last time anyone other than a Democrat held the position of Mayor in Buffalo was Chester A. Kowal in 1965. In 1977, Democratic Mayor James D. Griffin was elected as the nominee of two minor parties, the Conservative Party and the Right to Life Party, after he lost the Democratic primary for Mayor to then Deputy State Assembly Speaker Arthur Eve. Griffin switched political allegiances several times during his 16 years as Mayor, generally hewing to socially conservative platforms.

Griffin's successor, Democrat Anthony M. Masiello (elected in 1993) continued to campaign on social conservatism, often crossing party lines in his endorsements and alliances. However, in 2005, Democrat Byron Brown was elected the city's first African-American mayor in a landslide (64%–27%) over Republican Kevin Helfer, who ran on a conservative platform. In 2013, the Conservative Party endorsed Brown for a third term because of his pledge to cut taxes.[citation needed] This change in local politics was preceded by a fiscal crisis in 2003 when years of economic decline, a diminishing tax-base and civic mismanagement left the city deep in debt and on the edge of bankruptcy. At New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi's urging, the state took over the management of Buffalo's finances, appointing the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority. Mayor Tony Masiello began conversations about merging the city with the larger Erie County government the following year, but they came to nought.

The offices of the Buffalo District, US Army Corps of Engineers are next to the Black Rock Lock in the Erie Canal's Black Rock channel. In addition to maintaining and operating the lock, the District plans, designs, constructs and maintains water resources projects from Toledo, Ohio to Massena, New York. These include the flood-control dam at Mount Morris, New York, oversight of the lower Great Lakes (Lake Erie and Lake Ontario), review and permitting of wetlands construction, and remedial action for hazardous waste sites. Buffalo is also the home of a major office of the National Weather Service (NOAA), which serves all of western and much of central New York State. Buffalo is home to one of the 56 national FBI field offices. The field office covers all of Western New York and parts of the Southern Tier and Central New York. The field office operates several task forces in conjunction with local agencies to help combat issues such as gang violence, terrorism threats and health care fraud.[174] Buffalo is also the location of the chief judge, United States Attorney and administrative offices for the United States District Court for the Western District of New York.

Education

Overlooking the University at Buffalo's South Campus from Abbott Hall

Buffalo Public Schools serve most of the city of Buffalo. The city has 78 public schools, including a growing number of charter schools. As of 2006[update], the total enrollment was 41,089 students with a student-teacher ratio of 13.5 to 1. The graduation rate is up to 52% in 2008, up from 45% in 2007, and 50% in 2006.[175] More than 27% of teachers have a master's degree or higher and the median amount of experience in the field is 15 years. The metropolitan area has 292 schools with 172,854 students.[176]

Buffalo's magnet school system attracts students with special interests, such as science, bilingual studies, and Native American studies. Specialized facilities include the Buffalo Elementary School of Technology; the Dr Martin Luther King Jr., Multicultural Institute; the International School; the Dr. Charles R. Drew Science Magnet; BUILD Academy; Leonardo da Vinci High School; PS 32 Bennett Park Montessori; the Buffalo Academy for Visual and Performing Arts, BAVPA; the Riverside Institute of Technology; Lafayette High School/Buffalo Academy of Finance; Hutchinson Central Technical High School; Burgard Vocational High School; South Park High School; and the Emerson School of Hospitality.

Rockwell Hall, Buffalo State College

The city is home to 47 private schools and the metropolitan region has 150 institutions. Most private schools, such as Bishop Timon – St. Jude High School, Canisius High School, Mount Mercy Academy, and Nardin Academy have a Catholic affiliation. In addition, there are two Islamic schools, Darul Uloom Al-Madania and Universal School of Buffalo. There are also nonsectarian options including The Buffalo Seminary (the only private, nonsectarian, all-girls school in Western New York state),[177]Nichols School and numerous Charter Schools.

Private school tuition is approximately 40% less than Buffalo Public School's per student spending. Private schools graduate nearly 100% of students, public schools only approximately 30%.

Complementing its standard function, the Buffalo Public Schools Adult and Continuing Education Division provides education and services to adults throughout the community.[178] In addition, the Career and Technical Education Department offers more than 20 academic programs, and is attended by about 6,000 students each year.[179]

The State University of New York (SUNY) operates three institutions within the city of Buffalo. The State University of New York at Buffalo is known as "Buffalo" or "UB" and is the largest public university in New York.[180] The University at Buffalo is the only university in Buffalo and is a nationally ranked tier 1 research university.[181]Buffalo State College and Erie Community College are a college and a community college, respectively. Additionally, the private institutions Canisius College and D'Youville College are within the city.

Infrastructure

Healthcare

Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus as seen from the Erie Basin Marina observation tower

The city is home to two private healthcare systems, which combined operate eight hospitals and countless clinics in the greater metropolitan area, as well as three public hospitals operated by Erie County and the State of New York. Oishei Children's Hospital[182] opened in November 2017 and is the only long-standing children's hospital in New York. Buffalo General Medical Center and the Gates Vascular Institute have earned top rankings in the US for their cutting-edge research and treatment into the stroke and neurological care. Erie County Medical Center has been accredited as a Level One Trauma Center and serves as the trauma and burn care center for Western New York, much of the Southern Tier, and portions of Northwestern Pennsylvania and Ontario, Canada. Over the years, Roswell Park has also become recognized as one of the United States' leading cancer treatment and research centers, and it recruits physicians and researchers from across the world to come live and work in the Buffalo area.

- Mercy Hospital of Buffalo (South Buffalo)

Sisters of Charity Hospital (Central Buffalo)- Kenmore Mercy Hospital (Kenmore, NY)

- St. Joseph's Hospital (Cheektowaga, NY)

- Kaleida Health

- Buffalo General Medical Center/Gates Vascular Institute (Downtown Buffalo)

- Oishei Children's Hospital (Downtown Buffalo)

- DeGraff Memorial Hospital (North Tonawanda, NY)

- Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital (Amherst, NY)

The Erie County Medical Center (ECMC) (Eastern Buffalo)

Roswell Park Cancer Institute (Downtown Buffalo)

The Buffalo State Hospital (State-operated facility for the mentally ill, located in Northwest Buffalo)

Transportation

Buffalo Niagara International Airport

The 1955 Yellow Book planned the three major highways that would serve the Buffalo area: Interstate 190, Interstate 290, and Interstate 90.

Buffalo Metro Rail in downtown Buffalo

The Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority (NFTA) operates Buffalo Niagara International Airport, reconstructed in 1997 and located in the suburb of Cheektowaga.[citation needed] The airport serves Western New York and much of the Finger Lakes and Southern Tier Regions. The Buffalo Metro Rail, also operated by the NFTA, is a 6.4 miles (10.3 km) long,[citation needed] single line light rail system that extends from Erie Canal Harbor in downtown Buffalo to the University Heights district (specifically, the South Campus of University at Buffalo) in the city's northeastern part.[citation needed] The line's downtown section runs above ground and is free of charge to passengers.[citation needed] North of Fountain Plaza Station, at the northern end of downtown, the line moves underground until it reaches its northern terminus at University Heights. Passengers pay a fare to ride this section of the rail.[citation needed] Two train stations, Buffalo-Depew and Buffalo-Exchange Street, serve the city and are operated by Amtrak. Historically, the city was a major stop on through routes between Chicago and New York City through the lower Ontario peninsula.[183]

The Buffalo Outer Harbor in 1992. Northwest of the city is the Niagara River.

Buffalo is at the Lake Erie's eastern end and serves as a playground for many personal yachts, sailboats, power boats and watercraft.[citation needed] The city's extensive breakwall system protects its inner and outer harbors, which are maintained at commercial navigation depths for Great Lakes freighters.[citation needed] A Lake Erie tributary that flows through south Buffalo is the Buffalo River and Buffalo Creek.[184]

Eight New York State highways, one three-digit Interstate Highway and one U.S. Highway traverse the city of Buffalo. New York State Route 5, commonly referred to as Main Street within the city[citation needed], enters through Lackawanna as a limited-access highway and intersects with Interstate 190, a north-south highway connecting Interstate 90 in the southeastern suburb of Cheektowaga with Niagara Falls. NY 354 (Clinton Street) and NY 130 (Broadway) are east to west highways connecting south and downtown Buffalo to the eastern suburbs of West Seneca and Depew. NY 265 (Delaware Avenue) and NY 266 (Niagara Street and River Road) both start in downtown Buffalo and end in the city of Tonawanda. One of three U.S. highways in Erie County, the other two being U.S. 20 (Transit Road) and U.S. 219 (Southern Expressway), U.S. 62 (Bailey Avenue) is a north to south trunk road that enters the city through Lackawanna and exits at the Amherst town border at a junction with NY 5. Within the city, the route passes by light industrial developments and high-density areas of the city. Bailey Avenue has major intersections with Interstate 190 and the Kensington Expressway.

Three major expressways serve Buffalo. The Scajaquada Expressway (NY 198) is primarily a limited access highway connecting Interstate 190 near Unity Island to New York State Route 33, which starts at the edge of downtown and the city's East Side, continues through heavily populated areas of the city, intersects with Interstate 90 in Cheektowaga and ends at the airport. The Peace Bridge is a major international crossing near the city's Black Rock district that connects Buffalo with Fort Erie and Toronto via the Queen Elizabeth Way.[185]

The city of Buffalo has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 30 percent of Buffalo households lacked a car, and decreased slightly to 28.2 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Buffalo averaged 1.03 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[186]

Utilities

Buffalo's water system is operated by Veolia Water.[187] To reduce large-scale ice blockage in the Niagara River, with resultant flooding, ice damage to docks and other waterfront structures, and blockage of the water intakes for the hydro-electric power plants at Niagara Falls, the New York Power Authority and Ontario Power Generation have jointly operated the Lake Erie-Niagara River Ice Boom since 1964.[citation needed] The boom is installed on December 16, or when the water temperature reaches 4 °C (39 °F), whichever happens first.[citation needed] The boom is opened on April 1 unless there is more than 650 square kilometres (250 sq mi) of ice remaining in Eastern Lake Erie.[citation needed] When in place, the boom stretches 2,680 metres (8,790 ft) from the outer breakwall at Buffalo Harbor almost to the Canadian shore near the ruins of the pier at Erie Beach in Fort Erie.[citation needed] The boom was originally made of wooden timbers, but these have been replaced by steel pontoons.[188]

Media

A WIVB-TV truck during St. Patrick's Day

Buffalo's major newspaper is The Buffalo News. Established in 1880 as the Buffalo Evening News, the newspaper has 181,540 in daily circulation and 266,123 on Sundays.[citation needed] With the radio stations WBEN (later WBEN-AM), WBEN-FM, and television station WBEN-TV, Buffalo's first and for several years only television station, the Buffalo Evening News dominated the local media market until 1977, when the newspaper and the stations were separated. The stations showed their affiliation with the newspaper in their call sign: WBEN. Other newspapers in the Buffalo area include Artvoice, The Public,[189] and Buffalo Business First.

According to Nielsen Media Research, the Buffalo television market is the 52nd largest in the United States as of 2013[update].[190]

Movies shot with significant footage of Buffalo include: Hide in Plain Sight (1980),[191]Tuck Everlasting (1981),[191]Best Friends (1982),[191]The Natural (1984),[191]Vamping (1984),[191]Canadian Bacon (1995),[191]Buffalo '66 (1998),[191]Manna from Heaven (2002),[191]Bruce Almighty (2003),[192]The Savages (2007),[191]Henry's Crime (2011),[191]Sharknado 2: The Second One (2014),[192]Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of The Shadows (2016),[193]Marshall (2016),[192]Accidental Switch (2016), and The American Side (2017).[194] Although additional movies, such as Promised Land (2012), have used Buffalo as a setting, filming often takes place in other locations such as Pittsburgh or Canada. High production costs are blamed for filmmakers shooting all or most of their Buffalo-based scenes elsewhere.[195]

Notable people

Sister cities

Buffalo has a number of sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International (SCI):[196][197]

|

|

|

See also

- Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo

Notes and references

Notes

^ Josephy, p. 189, [with the Neutrals]... " broken in 1651, with mopping up continuing for several years."

^ Formerly known as Stadtnitski, Vollenhoven and Schimmelpennick Avenues, removed after backlash by village residents.

^ When travelling with an ox and wagon team.

^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

^ Official records for Buffalo kept January 1871 to June 1943 at downtown and at Buffalo Niagara Int'l since July 1943. For more information, see Threadex

References

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 29, 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Ketchum 1865, p. 63–65.

^ Severance, Frank H. (1902). "The Achievements of Captain John Montresor". In Buffalo Historical Society. Buffalo Historical Society Publications. Buffalo, NY: Bigelow Brothers. p. 15. Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

^ ab You asked us: The 868–3900 line to your desk at the Star: How Buffalo got its name, Toronto Star, Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Toronto Star, September 24, 1992, Stefaniuk, W., Retrieved April 23, 2014.

^ ab Worldly setting, sophisticated choices, atmosphere at Beau Fleuve, Buffalo News, Buffalo, NY: Berkshire Hathaway, March 19, 1993, Okun, J., Retrieved April 23, 2014.

^ ab 'Beau Fleuve' story doesn't wash, Buffalo News, Buffalo, NY: Berkshire Hathaway, July 21, 2003, Retrieved April 23, 2014.

^ Hornaday, William T. (1889). "Geographic Distribution". The Extermination of the American Bison. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 385–386. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

^ Sprague 1882, pp. 17–18.

^ ab Thompson 1977, p. 113.

^ Thompson 1977, pp. 114–115, 117.

^ Bingham 1931, p. 1.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 118.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 117–118.

^ abc Editor: Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., by The editors of American Heritage Magazine (1961). "The American Heritage Book of Indians". In pages 187–219. ,. American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc. p. 189. LCCN 61-14871.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Bingham 1931, p. 5.

^ Houghton, Frederick (1927). "The Migrations of the Seneca Nation". American Anthropologist. 29: 241–250. doi:10.1525/aa.1927.29.2.02a00050.

^ Donehoo, George P. (1922). The Indians of the Past and of the Present. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. p. 181. JSTOR 20086480.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 119.

^ Becker 1906, pp. 15–20.

^ Turner 1849, p. 119–126.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 140.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 148.

^ Sprague 1882, p. 19.

^ Becker 1906, p. 108.

^ Thompson 1977, p. 141.

^ ab Brush 1901, p. 87.

^ Becker 1906, pp. 106–108.

^ Bingham 1931, pp. 137–138.

^ Sprague 1882, pp. 20, 21.

^ Becker 1906, p. 106–107.

^ Ketchum 1865, p. 141.

^ Bingham 1931, pp. 132–134.

^ Turner 1849, p. 401.

^ Bingham 1931, p. 145.

^ Bartlett, George Hunter (1922). Recalling Pioneer Days. The Buffalo Historical Society. p. 3. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

^ Stewart, John (1899). "Early Maps and Surveyors of the City of Washington, D. C.". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 2: 58. doi:10.2307/40066723. JSTOR 40066723.

^ Bingham & 1931 146.

^ ab Becker 1906, p. 111.

^ ab Fernald, Frederik Atherton (1910). The index guide to Buffalo and Niagara Falls. The Library of Congress. Buffalo, N.Y., F.A. Fernald. p. 21. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

^ Clinton, George W.; Hunt, Sanford B. (1862). Thomas' Buffalo City Directory for 1862, to which is Prefixed a Sketch of the Early History of Buffalo. Buffalo, NY: E.A. Thomas, Franklin Steam Printing House. p. 16. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

^ French & Place 1860, p. 210.

^ Elmendorf, Dwight L. (March 1913). "Washington the Capital". The Mentor. 1: 2.

^ abc Turner 1849, p. 439.

^ Powell, Elwin Humphreys (1988-01-01). The Design of Discord: Studies of Anomie. Transaction Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 9781412836494.

^ Myers, Stephen G. (2012). Buffalo. Arcadia Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9780738591650.

^ Myers, Stephen G. (2012). Buffalo. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738591650.

^ Buffalo Historical Society (1882). Semi-centennial Celebration of the City of Buffalo: Address of the Hon. E.C. Sprague Before the Buffalo Historical Society, July 3, 1882. Buffalo, N.Y.: Buffalo Historical Society. pp. 20, 21.

^ Turner 1849, p. 498.

^ Becker 1906, p. 114–115.

^ Becker 1906, pp. 111, 118.

^ Bingham 1931, p. 493.

^ ab Becker 1906, p. 115.

^ ab Thompson 1977, p. 152.

^ Turner 1849, p. 494.

^ Turner 1849, p. 495.

^ Bingham 1931, pp. 356–357.

^ Becker 1906, p. 115, 118.

^ Becker 1906, p. 119.

^ Becker 1906, pp. 120–121.

^ ab Berton, Pierre (1981). Flames across the border : the Canadian-American tragedy, 1813-1814. Boston : Little, Brown. pp. 126, 262–268. ISBN 9780316092173. OCLC 421827788.

^ Becker 1906, pp. 126–127.

^ abc Severance, Frank H. (1879). "Papers relating to the Burning of Buffalo". Publications of the Buffalo Historical Society. Harold B. Lee Library. Buffalo : Bigelow Bros. pp. 334–356.

^ Quimby, Robert (1997). The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. p. 355. ISBN 0-87013-441-8.

^ Gee, Denise Jewell (December 30, 2013). "200 years ago, the village of Buffalo burned". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

^ "The Buffalo of Yesteryear: Chictawauga, Scajaquady and the 'morass' that was Buffalo". The Buffalo News. November 29, 2017. Archived from the original on November 29, 2017. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

^ Becker 1906, p. 125–126.

^ Becker 1906, p. 131.

^ Becker 1906, p. 132.

^ Bingham 1931, p. 385.

^ "Erie Canal opens". The History Channel website. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

^ Proceedings of the Common Council of the City of Buffalo. James D. Warren's Sons Co. 1909. p. 2262.

^ "Canal History". New York State Canals. New York State Canal Corporation. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

^ Champieux, Robin (April 2003). "John W. Clark papers". William L. Clements Library. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

^ ab "A Brief Chronology of the Development of the City of Buffalo". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

^ The Manufacturing Interests of the City of Buffalo: Including Sketches of the History of Buffalo. With Notices of Its Principal Manufacturing Establishments. C.F.S. Thomas. 1866. p. 13.

^ Goldman 1983, p. 72.

^ Goldman 1983, pp. 72–74.

^ Goldman 1983, pp. 75–76.

^ Goldman 1983, p. 87.

^ Savage, Beth L.; Shull, Carol D. (1994). African American Historic Places. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press. pp. 346–347. ISBN 9780471143451. LCCN 94033218. OCLC 30976865.

^ Switala, William J. (2014-05-14). Underground Railroad in New York and New Jersey. Stackpole Books. p. 126. ISBN 9780811746298.

^ Priebe Jr., J. Henry. "The City of Buffalo 1840–1850". Archived from the original on September 5, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

^ Baxter, Henry. "Grain Elevators" (PDF). Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

^ Kowsky, Francis R. (2006). "Monuments of a Vanished Prosperity: Buffalo's Grain Elevators and the Rise and Fall of the Great Transnational System of Grain Transport". In Schneekloth, Lynda H. Reconsidering Concrete Atlantis: Buffalo Grain Elevators (PDF). The Urban Design Project, School of Architecture and Planning, University at Buffalo. pp. 24–25. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2016.

^ French & Place 1860, pp. 66–74.

^ French & Place 1860, p. 286.

^ "ELECTRIC LIGHTS TO OPTICS RESEARCH: BUFFALO, "CITY OF LIGHT", by Amanda Marie Rogers, New York Makers, December 18, 2013

^ Believe it, or not. Clymer, Floyd. Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877–1925 (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.178.

^ Dillaway 2006, p. 28–30.

^ "President William McKinley is shot". The History Channel website. Archived from the original on October 14, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

^ ab "Swearing-In Ceremony for President Theodore Roosevelt". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

^ * Lansky, Lewis. "Buffalo and the Great Depression, 1929–1933," in Milton Plesur, ed., American Historian: Essays to Honor Selig Adler (1980), pp 204–13

^ "1941–1945". History. Parkside Community Association. Archived from the original on July 8, 2010.

^ Rizzo, Michael. "Joseph J. Kelly 1942–1945". Through The Mayor's Eyes. The Buffalonian. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011.

^ Goldman 1983, p. 270.

^ Goldman 1983, p. 271.

^ ab "Back in business". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. June 30, 2012. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

^ ab Goldman 1983, pp. 270–271, 294.

^ "Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1950". United States Census. June 15, 1998. Archived from the original on August 24, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

^ Koritz, Douglas. "Restructuring or Destructuring?". Urban Affairs Quarterly. 26 (4): 497–511. doi:10.1177/004208169102600403.

^ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (June 23, 2014). "Buffalo, New York". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

^ Editors (May 17, 2010). "Encyclopaedia Britannica". www.britannica.com/place/Niagara-River. Encyclopaedia Britannica, INc. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

^ Luther, D. D. (1906). Geologic map of the Buffalo quadrangle. Columbia University Libraries. New York State Education Dept.

^ "UB Geologists Find Evidence That Upstate New York Is Criss-Crossed By Hundreds Of Faults - University at Buffalo". www.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

^ Smith, Henry Perry (1884). History of the city of Buffalo and Erie County : with ... biographical sketches of some of its prominent men and pioneers ... Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co. p. 16.

^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (November 14, 2008). "Saving Buffalo's Untold Beauty". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ "Buffalo, NY". Forbes. Forbes.com LLC. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ Karson, Robin (January 21, 2014). The Best Planned City: Olmsted, Vaux, and the Buffalo Park System (Motion picture). Library of American Landscape History.

^ "Louis Sullivan still has a skyscraper in Buffalo, but Chicago has none". Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

^ E. Kaplan, Marilyn (June 1989). "Preservation Tech Notes: Guaranty Building" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

^ Miller, Melinda (November 17, 2013). "Preparing for 38 floors of emptiness at One Seneca Tower". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11: 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2012.

^ abcdefg "Buffalo's Climate". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

^ Madsen, Steve. "Comparison Golden Snowball City Stats 1940 – 2007". Goldensnowball. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014., Retrieved May 31, 2013.

^ WeatherBug Meteorologists (January 3, 2012). "What Are The Snowiest Cities in the U.S.?". Weatherbug. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014., Retrieved May 31, 2013.

^ "Buffalo remembers infamous blizzard of '77". USA Today. June 1, 2002. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

^ "Buffalo socked by wintry October surprise". WISTV. October 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

^ "October Surprise Storm: 7th Anniversary". WGRZ. Gannett. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014.

^ McClam, Erin; Arkin, Daniel (20 November 2014). "Buffalo, Western New York Buried by Another Wave of Snow – NBC News". NBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

^ "Record high of 99 °F (37 °C) was recorded in August 1948". Weather.com. July 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013.

^ "August Daily Averages for Buffalo, NY". weather.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

^ "February Daily Averages for Buffalo, NY". weather.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2014. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

^ "Station Name: NY BUFFALO". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

^ "WMO Climate Normals for Buffalo/Greater Buffalo, NY 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 10, 2013.

^ "Census" (PDF). United States Census. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2013. page 36

^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Archived from the original on April 22, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

^ "Buffalo (city), New York". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014.

^ abc "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012.

^ From 15% sample

^ "Buffalo Demographics: 2010". quickfacts.census.go. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

^ Zremski, Jerry; Gee, Derek (October 16, 2016). "From Burma to Buffalo, The refugee wave is changing our city". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

^ Rott, Jerry (July 26, 2013). "List: Largest Employers". Buffalo Business First. American City Business Journals. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ [1]/ Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Poverty USA – Catholic Campaign for Human Development – A hand up, not a hand out". Usccb.org. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011.

^ Buffalo 3rd Poorest Large City Archived January 5, 2013, at Archive.is. WGRZ TV. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

^ Buffalo falls to second-poorest big city in U.S., with a poverty rate of nearly 30 percent. Buffalo News. Retrieved September 2, 2007.[dead link]

^ "Buffalo Market Trends". Trulia. Archived from the original on September 9, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ "Buffalo Economy News". City of Buffalo. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

^ "Signs of economic revival finally appear". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

^ New York State Department of Labor (April 21, 2015). "State Labor Department Releases Preliminary March 2015 Area Unemployment Rates". Labor.ny.gov. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

^ National Conference of State Legislatures (April 3, 2015). "National Employment Monthly Update". Ncsl.org. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

^ Thomas, G. Scott (February 16, 2016). "Which industries are driving the Buffalo area's economy? Here are the top 10". Buffalo Business First. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2016.

^ "Crime rate in Buffalo, New York (NY): murders, rapes, robberies, assaults, burglaries, thefts, auto thefts, arson, law enforcement employees, police officers, crime map". city-data.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

^ Thomas, G. Scott. "New FBI report: Buffalo's violent-crime rate is 15th-worst in the nation". bizjournals. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

^ "The World's Top Ten Food Cities". National Geographic. February 2015. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

^ "Famous Buffalo and Western New York Foods, Restaurants & Food Festivals". Buffalo Chow.com. Archived from the original on September 7, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

^ "Top 100 Buffalo/WNY Foods (and Restaurants), Part 1 of 5". Buffalo Chow.com. February 10, 2009. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

^ Addotta, Kip. "Pizza!". Kip Addotta dot com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

^ Horwitz, Jeremy (January 2008). "Loganberry: The Buffalo Drink You'll Like or Love". Buffalo Chow.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

^ Trillin, Calvin. "The New Yorker". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013.

^ Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (2013). History of Non-Dairy Whip Topping, Coffee Creamer, Cottage Cheese, and Icing/Frosting (With and Without Soy) (1900–2013) (PDF). p. 6. ISBN 978-1-928914-62-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2016.

^ "Leading Businesses and Brands". Buffalo Niagara Enterprise. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ World Grain Staff (May 13, 2013). "ADM to reopen flour mill after fire". World-Grain Report., Retrieved May 31, 2013.

^ "Who We Are – A Global Leader in Hospitality and Food Service". Delaware North Companies Homepage. Archived from the original on January 26, 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

^ Algonquin Studios. "City of Buffalo Public Art Collection". City-buffalo.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013.

^ "Burchfield Penney Art Center". www.burchfieldpenney.org. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

^ Menzie, Karol. "Top 25 Mid-Size Cities for Art". AmericanStyle. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

^ Healy, Patrick (December 23, 2011). "Shea's Performing Arts Center in Buffalo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

^ Unofficial, Unbiased Guide to the 331 Most Interesting Colleges 2005. Simon and Schuster. 2004. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2013.