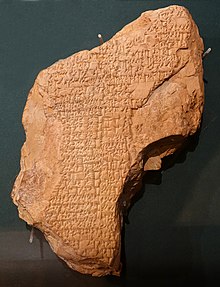

Clay tablet

List of the victories of Rimush, king of Akkad, upon Abalgamash, king of Marhashi, and upon Elamitemonumental inscription, ca. 2270 BC. (see Obelisk)

In the Ancient Near East, clay tablets (Akkadian ṭuppu(m) 𒁾)[1] were used as a writing medium, especially for writing in cuneiform, throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age.

Cuneiform characters were imprinted on a wet clay tablet with a stylus often made of reed (reed pen). Once written upon, many tablets were dried in the sun or air, remaining fragile. Later, these unfired clay tablets could be soaked in water and recycled into new clean tablets. Other tablets, once written, were fired in hot kilns (or inadvertently, when buildings were burnt down by accident or during conflict) making them hard and durable. Collections of these clay documents made up the very first archives. They were at the root of first libraries. Tens of thousands of written tablets, including many fragments, have been found in the Middle East.[2][3]

In the Minoan/Mycenaean civilizations, writing has not been observed for any use other than accounting. Tablets serving as labels, with the impression of the side of a wicker basket on the back, and tablets showing yearly summaries, suggest a sophisticated accounting system. In this cultural region the tablets were never fired deliberately, as the clay was recycled on an annual basis. However, some of the tablets were "fired" as a result of uncontrolled fires in the buildings where they were stored. The rest are still tablets of unfired clay, and extremely fragile; some modern scholars are investigating the possibility of firing them now, as an aid to preservation.[citation needed]

Contents

1 Scribes

2 Uses of clay tablets

3 Communication

4 Proto-writing

5 History by region

5.1 Babylonia

6 See also

7 References

8 External links

Scribes

Writing was not as we see it today. In Mesopotamia, it started out as simple counting marks, alongside which sometimes a non-arbitrary well understood the sign, in the form of a simple picture image, that was cut into wood, stone, pots but more often pressed onto clay tokens. In that way, recorded accounts of amounts of goods involved in a transaction could be made. This convention began when people developed agriculture and settled into permanent communities that were centered on increasingly large and organized trading marketplaces[4] These marketplaces traded sheep, grain, and bread loaves, recording the transactions with clay tokens. These initially very small clay tokens were continually used all the way from the pre-historic Mesopotamia period, 9000 BC, to the start of the historic period around 3000 BC, when the use of writing for recording was widely adopted.[4]

The clay tablet was thus being used by scribes to record events happening during their time. Tools that these scribes used were styluses with sharp triangular tips, making it easy to leave markings on the clay;[5] the clay tablets themselves came in a variety of colors such as bone white, chocolate, and charcoal.[6]Pictographs then began to appear on clay tablets around 4000 BC, and after the later development of Sumerian cuneiform writing, a more sophisticated partial syllabic script evolved that by around 2500 BC was capable of recording the vernacular, the everyday speech of the common people.[6]

Sumerians used what is known as pictograms.[4] Pictograms are symbols that express a pictorial concept, a logogram, as the meaning of the word. Early writing also began in Ancient Egypt using hieroglyphs. Early hieroglyphs and some of the modern Chinese characters are other examples of pictographs. The Sumerians later shifted their writing to Cuneiform, defined as "Wedge writing" in Latin, which added phonetic symbols, syllabograms.[5]

Uses of clay tablets

Sumerian clay tablet, currently housed in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, inscribed with the text of the poem Inanna and Ebih by the priestess Enheduanna, the first author whose name is known[7]

Text on clay tablets took the forms of myths, fables, essays, hymns, proverbs, epic poetry, laws, plants, and animals.[6] What these clay tablets allowed was for individuals to record who and what was significant. An example of these great stories was The Story of Gilgamesh. This story would tell of the great flood that destroyed Sumer. Remedies and recipes that would have been unknown were then possible because of the clay tablet. Some of the recipes were stew, which was made with goat, garlic, onions and sour milk.

By the end of the 3rd Millennium BC, (2200-2000 BC), even the "short story" was first attempted, as independent scribes entered into the philosophical arena, with stories like: The Debate between Bird and Fish, and other topics, (List of Sumerian debates).

Communication

Communication grew faster as now there was a way to get messages across just like mail. Important and private clay tablets were coated with an extra layer of clay, that no one else would read it. This means of communicating was used for over[6] 3000 years in fifteen different languages. Sumerians, Babylonians and Eblaites all had their own clay tablet libraries.

Proto-writing

The Tărtăria tablets, the Danubian civilization, may be still older, having been dated by indirect method (bones found near the tablet were carbon dated) to before 4000 BC, and possibly dating from as long ago as 5500 BC, but their interpretation remains controversial because the tablets were fired in a furnace and the properties of the carbon changed accordingly.[8]

History by region

Babylonia

Fragments of tablets containing the Epic of Gilgamesh dating to 1800-1600BC have been discovered. A full version has been found on tablets dated to the 1st millennium BC.[9]

Tablets on Babylonian astronomical records date back to around 1800BC. Tablets discussing astronomical records continue through around 75AD.[10]

Late Babylonian tablets at the British Museum refer to appearances of Halley's Comet in 164BC and 87BC.[11]

See also

- Clay tokens system

- Code of Hammurabi

- Sanskrit

Complaint tablet to Ea-nasir, the oldest known complaint letter

References

^ Black, Jeremy Allen; George, Andrew R.; Postgate, Nicholas (2000). A concise dictionary of Akkadian (2nd ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 415. ISBN 978-3-447-04264-2. LCCN 00336381. OCLC 44447973..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Guisepi, Robert Anthony; F. Roy Willis (2003). "Ancient Sumeria". International World History Project. Robert A. Guisepi. Retrieved 5 November 2010. External link in|work=(help)

^ The Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative gives an estimate of 500,000 for the total number of tablets (or fragments) that have been found.

^ abc "Early Writing". Harry Ransom Center - University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

^ ab "Cuneiform - Ancient History Encyclopedia". Ancient.eu.com. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

^ abcd Cuneiform, Sumerian tablets and the world's oldest writing (factanddetails.com)

^ Roberta Binkley (2004). "Reading the Ancient Figure of Enheduanna". Rhetoric before and beyond the Greeks. SUNY Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780791460993.

^

Ioana Crişan; Marco Merlini. "Signs on Tartaria Tablets found in the Romanian folkloric art". Prehistory Knowledge. The Global Prehistory Consortium, Euro Innovanet. Retrieved 5 November 2010. External link in|work=(help)

^ Kovacs, transl., with an introd. by Maureen Gallery (2004). The epic of Gilgamesh (Nachdr. ed.). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univ. Press. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 0804717117.

^ Thurston, Hugh (1996). Early astronomy (Springer study ed.). New York: Springer. pp. 64–81. ISBN 0387948228.

^ Stephenson, F. R.; Yau, K. K. C.; Hunger, H. (April 1985). "Records of Halley's comet on Babylonian tablets". Nature. 314 (6012): 587–592. doi:10.1038/314587a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clay tablets. |