Pre-Pottery Neolithic

| |

| Geographical range | Fertile Crescent |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic |

| Dates | circa 8,500 B.C.E. — circa 5,500 B.C.E. |

| Type site | Jericho |

| Preceded by | Natufian culture |

| Followed by | Halaf culture, Neolithic Greece, Faiyum A culture |

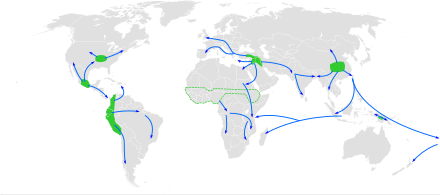

Map of the world showing approximate centers of origin of agriculture and its spread in prehistory: the Fertile Crescent (11,000 BP), the Yangtze and Yellow River basins (9,000 BP) and the New Guinea Highlands (9,000–6,000 BP), Central Mexico (5,000–4,000 BP), Northern South America (5,000–4,000 BP), sub-Saharan Africa (5,000–4,000 BP, exact location unknown), eastern North America (4,000–3,000 BP).[1]

| The Neolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Mesolithic |

|

farming, animal husbandry |

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPN, around 8500-5500 BCE)[2] represents the early Neolithic in the Levantine and upper Mesopotamian region of the Fertile Crescent. It succeeds the Natufian culture of the Epipaleolithic (Mesolithic), as the domestication of plants and animals was in its formative stages, having possibly been induced by the Younger Dryas. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture came to an end around the time of the 8.2 kiloyear event, a cool spell centred on 6200 BCE that lasted several hundred years.

Contents

1 Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

2 Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

3 Pre-Pottery Neolithic C

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

Pre-Pottery Neolithic A

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic is divided into Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA 8500 BCE - 7600 BCE) and the following Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB 7600 BCE - 6000 BCE).[3] These were originally defined by Kathleen Kenyon in the type site of Jericho (Palestine). The Pre-Pottery Neolithic precedes the ceramic Neolithic (Yarmukian). At 'Ain Ghazal in Jordan the culture continued a few more centuries as the so-called Pre-Pottery Neolithic C culture.

Around 8000 BCE during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) the world's first town Jericho appeared in the Levant.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

PPNB differed from PPNA in showing greater use of domesticated animals, a different set of tools, and new architectural styles.

Pre-Pottery Neolithic C

Work at the site of 'Ain Ghazal in Jordan has indicated a later Pre-Pottery Neolithic C period. Juris Zarins has proposed that a Circum Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex developed in the period from the climatic crisis of 6200 BCE, partly as a result of an increasing emphasis in PPNB cultures upon domesticated animals, and a fusion with Harifian hunter gatherers in the Southern Levant, with affiliate connections with the cultures of Fayyum and the Eastern Desert of Egypt. Cultures practicing this lifestyle spread down the Red Sea shoreline and moved east from Syria into southern Iraq.[4]

See also

- Pre-history of the Southern Levant

- History of pottery in the Southern Levant

References

^ Diamond, J.; Bellwood, P. (2003). "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions". Science. 300 (5619): 597–603. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..597D. doi:10.1126/science.1078208. PMID 12714734..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Richard, Suzanne Near Eastern archaeology Eisenbrauns; illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004)

ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5 p.244 [1]

^ Richard, Suzanne Near Eastern archaeology Eisenbrauns; illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004)

ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5 p.244 [2]

^ Zarins, Juris (1992) "Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record," in Ofer Bar-Yosef and A. Khazanov, eds. "Pastoralism in the Levant"

Further reading

Ofer Bar-Yosef, The PPNA in the Levant – an overview. Paléorient 15/1, 1989, 57-63.- J. Cauvin, Naissance des divinités, Naissance de l’agriculture. La révolution des symboles au Néolithique (CNRS 1994). Translation (T. Watkins) The birth of the gods and the origins of agriculture (Cambridge 2000).