Zapatista Army of National Liberation

| Zapatista Army of National Liberation | |

|---|---|

Participant in Chiapas conflict | |

Flag of the EZLN | |

| Active | 1994–present |

| Ideology | Neozapatismo Anti-imperialism Anti-capitalism Alter-globalization Libertarian socialism Anarcha-feminism Radical democracy |

| Political position | Left-wing to far-left |

| Leaders |

|

| Area of operations | Chiapas, Mexico |

| Size | About 3,000 active participants and militia; tens of thousands of civilian supporters (bases de apoyo) |

The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, EZLN), often referred to as the Zapatistas [sapaˈtistas], is a left-wing libertarian-socialist political and militant group that controls a large amount of territory in Chiapas, the southernmost state of Mexico.

Since 1994 the group has been in a declared war against the Mexican state, and against military, paramilitary and corporate incursions into Chiapas.[1] This war has been primarily defensive. In recent years, the EZLN has focused on a strategy of civil resistance. The Zapatistas' main body is made up of mostly rural indigenous people, but it includes some supporters in urban areas and internationally. The EZLN's main spokesperson is Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, previously known as Subcomandante Marcos (a.k.a. Compañero Galeano and Delegate Zero in relation to "the Other Campaign"). Unlike other Zapatista spokespeople, Marcos is not an indigenous Maya.[2]

The group takes its name from Emiliano Zapata, the agrarian reformer and commander of the Liberation Army of the South during the Mexican Revolution, and sees itself as his ideological heir. Nearly all EZLN villages contain murals with images of Zapata, Ernesto "Che" Guevara, and Subcomandante Marcos.[3]

Although the ideology of the EZLN reflects libertarian socialism, paralleling both anarchist and libertarian Marxist thought in many respects, the EZLN has rejected[4] and defied[5] political classification, retaining its distinctiveness due in part to the importance of indigenous Mayan beliefs to the Zapatistas. The EZLN aligns itself with the wider alter-globalization, anti-neoliberal social movement, seeking indigenous control over their local resources, especially land. Since their 1994 uprising was countered by the Mexican army, the EZLN has abstained from military offensives and adopted a new strategy that attempts to garner Mexican and international support.

Contents

1 Organization

2 History

2.1 1990s

2.1.1 Military offensive

2.2 2000s

2.3 2010s

3 Ideology

3.1 Women's Revolutionary Law

3.2 Postcolonial gaze

4 Communications

5 Horizontal autonomy and indigenous leadership

6 Notable members

7 In popular culture

8 See also

9 References

9.1 Footnotes

9.2 Bibliography

10 Further reading

11 External links

Organization

Subcommander Marcos surrounded by several commanders of the CCRI

The Zapatistas describe themselves as a decentralized organization. The pseudonymous Subcommandante Marcos is widely considered its leader despite his claims that the group has no single leader. Political decisions are deliberated and decided in community assemblies. Military and organizational matters are decided by the Zapatista area elders who compose the General Command (Revolutionary Indigenous Clandestine Committee – General Command, or CCRI-CG).[6]

History

Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (Zapatista Army of National Liberation, or EZLN) was founded on November 17, 1983 by non-indigenous members of the FLN guerrilla (Fuerzas de Liberación Nacional founded by César Germán Yáñez Muñoz) group from Mexico's urban north and by indigenous inhabitants of the remote Las Cañadas/Selva Lacandona regions in eastern Chiapas, by members of former rebel movements. Over the years, the group slowly grew, building on social relations among the indigenous base and making use of an organizational infrastructure created by peasant organizations and the Catholic church (see Liberation theology).

1990s

The Zapatista Army went public on January 1, 1994, the day when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into effect. On that day, they issued their First Declaration and Revolutionary Laws from the Lacandon Jungle. The declaration amounted to a declaration of war on the Mexican government, which they considered so out of touch with the will of the people as to make it illegitimate. The EZLN stressed that it opted for armed struggle due to the lack of results achieved through peaceful means of protest (such as sit-ins and marches).[7]

Their initial goal was to instigate a revolution against the rise of neoliberalism[8] throughout Mexico, but since no such revolution occurred, they used their uprising as a platform to call the world's attention to their movement to protest the signing of NAFTA, which the EZLN believed would increase the gap between rich and poor people in Chiapas—a prediction affirmed by subsequent developments.[9] Gaining attention on a global level through their convention called the Intercontinental Encounter for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism that was attended by 3,000 activists worldwide, the Zapatistas were able to help initiate a united platform for other anti-neoliberal groups. This project did not detract from the Zapatistas' national activism efforts, but rather expanded their already existent ideologies.[8] The EZLN also called for greater democratization of the Mexican government, which had been controlled by the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Institutional Revolutionary Party, also known as PRI) for 65 years, and for land reform mandated by the 1917 Constitution of Mexico but largely ignored by the PRI.[10] The EZLN did not demand independence from Mexico, but rather autonomy in the form of land access and use of natural resources normally extracted from Chiapas, as well as protection from despotic violence and political inclusion of Chiapas' indigenous communities.[11]

On the morning of January 1, 1994, an estimated 3,000 armed Zapatista insurgents seized towns and cities in Chiapas, including Ocosingo, Las Margaritas, Huixtán, Oxchuc, Rancho Nuevo, Altamirano, and Chanal. They freed the prisoners in the jail of San Cristóbal de las Casas and set fire to several police buildings and military barracks in the area. The guerrillas enjoyed brief success, but Mexican army forces counterattacked the next day, and fierce fighting broke out in and around the market of Ocosingo. The Zapatista forces took heavy casualties and retreated from the city into the surrounding jungle.

Armed clashes in Chiapas ended on January 12, with a ceasefire brokered by the Catholic diocese in San Cristóbal de las Casas under Bishop Samuel Ruiz, a well known liberation theologian who had taken up the cause of the indigenous people of Chiapas. The Zapatistas retained some of the land for a little over a year, but in February 1995 the Mexican army overran that territory in a surprise breach of ceasefire. Following this offensive, the Zapatista villages were mostly abandoned, and the rebels fled to the mountains after breaking through the Mexican army perimeter.

Military offensive

Once Subcomandante Marcos was identified as Rafael Guillén on February 9, 1995, in a turn of events counterproductive to the understandings the Mexican Government and the EZLN had reached, Mexican President Ernesto Zedillo made a series of decisions that were completely at odds with the strategic plan previously defined by his government, and with the agreements he had authorized his Secretary of Interior, Lic Esteban Moctezuma, to discuss with Marcos a mere three days earlier, in Guadalupe Tepeyac - Zedillo sent the Mexican army to capture or annihilate Marcos, without first consulting his Secretary of Interior, without knowing exactly who Marcos was, and only with the PGR's single presumption that Marcos was a dangerous guerrilla. Despite these circumstances, President Zedillo decided to launch a military offensive in an attempt to capture or annihilate the EZLN's main spokesperson, a figure around which a cult of personality was already forming.

Arrest-warrants were made for Marcos, Javier Elorriaga Berdegue, Silvia Fernández Hernández, Jorge Santiago, Fernando Yanez, German Vicente, Jorge Santiago and other Zapatistas. At that point, in the Lacandon Jungle, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation was under military siege by the Mexican Army. Javier Elorriaga was captured on February 9, 1995, by forces from a military garrison at Gabina Velázquez in the town of Las Margaritas, and was later taken to the Cerro Hueco prison in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas.

[12]

On February 11, 1995, the PGR informed the country that the government had implemented an operation in the State of México, where they had captured 14 people presumed to be involved with the Zapatistas, of which eight had already being turned over to the judicial authorities. They had also seized an important arsenal, the PGR stated.

[13] The PGR's repressive acts reached the point of threatening the San Cristóbal de Las Casas' Catholic Bishop, Samuel Ruiz García, with arrest, for allegedly aiding to conceal the Zapatistas' guerrilla uprising, even though their activities were reported years before the uprising in what is considered one of Mexico's most important magazines, Proceso, which the Mexican Government had tried to cover up.[14][15][16] This dealt a serious blow to the recently restored Mexico-Vatican diplomatic relationship,[17] taking into account the May 24, 1993 political assassination of a Prince of the Catholic Church, the Guadalajara Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo, that the PGR has left unresolved to this day.

Marcos's resolve was put to the test when the Zapatista Army of National Liberation was under military siege by the Mexican Army in their camp and in the Lacandon Jungle. Marcos's response was immediate, sending the then Secretary of Interior, Lic. Esteban Moctezuma, with whom he had met three days earlier, the following message: "See you in hell". The facts seemed to confirm former Chiapas Peace Commissioner Manuel Camacho Solis's accusations, made public in June 16, 1994, that the reason for his resignation was sabotage, done by the then presidential candidate Zedillo.

Under the considerable political pressure of a highly radicalized situation, and believing a peaceful solution to be possible, Mexican Secretary of the Interior Lic. Esteban Moctezuma campaigned to reach a peacefully negotiated solution to the 1995 Zapatista Crisis, betting it all on a creative strategy to reestablish a dialogue between the Mexican Government and the EZLN to find peace, by demonstrating to Marcos the terrible consequences of a military solution.

Making a strong position against the February 9 actions against Peace, Moctezuma, defender of a political solution, submitted his resignation to President Zedillo, but the Zedillo refused to accept it. Moved by Moctezuma's protest, President Zedillo abandoned the military offensive in favor of the improbable task of restoring the conditions for dialog to reach a negotiation. For these foregoing reasons the Mexican army eased its operation in Chiapas, giving an opportunity that Marcos needed to escape the military perimeter in the Lacandon jungle.[18] Faced with this situation, Max Appedole, Rafael Guillén, childhood friend and colleague, at the Jesuits College Instituto Cultural Tampico asked for help from Edén Pastora the legendary Nicaraguan "Commander Zero" to prepare a report for under-Secretary of the Interior Luis Maldonado Venegas; the Secretary of the Interior Esteban Moctezuma and the President Zedillo about Marcos natural pacifist vocation and the terrible consequences of a tragic outcome.[19] The document concluded that the marginalized groups and the radical left that exist in México, have been vented with the Zapatistas movement, while Marcos maintains an open negotiating track. Eliminate Marcos, and his social containment work will not only cease, but will give opportunity to the radical groups to take control of the movement. They will respond to violence with violence. They would begin terrorist bombings, kidnappings and belligerent activities. The country would be in a very dangerous spiral, which could lead to very serious situations, because there is discontent not only in Chiapas, but also in many other places in Mexico.[20]

2000s

With the coming to power of the new government of President Vicente Fox in 2001 (the first non-PRI president of Mexico in over 70 years), the Zapatistas marched on Mexico City to present their case to the Mexican Congress. Although Fox had stated earlier that he could end the conflict "in fifteen minutes",[21] the EZLN rejected watered-down agreements and created 32 "autonomous municipalities" in Chiapas, thus partially implementing their demands without government support but with some funding from international organizations.

Subcomandante Marcos in 1996

On June 28, 2005, the Zapatistas presented the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle[22] declaring their principles and vision for Mexico and the world. This declaration reiterates the support for the indigenous peoples, who make up roughly one-third of the population of Chiapas, and extends the cause to include "all the exploited and dispossessed of Mexico". It also expresses the movement's sympathy to the international alter-globalization movement and offers to provide material aid to those in Cuba, Bolivia, Ecuador, and elsewhere, with whom they make common cause. The declaration ends with an exhortation for all who have more respect for humanity than for money to join with the Zapatistas in the struggle for social justice both in Mexico and abroad. The declaration calls for an alternative national campaign (the "Other Campaign") as an alternative to the presidential campaign. In preparation for this campaign, the Zapatistas invited to their territory over 600 national leftist organizations, indigenous groups, and non-governmental organizations in order to listen to their claims for human rights in a series of biweekly meetings that culminated in a plenary meeting on September 16, the day Mexico celebrates its independence from Spain. In this meeting, Subcomandante Marcos requested official adherence of the organizations to the Sixth Declaration, and detailed a six-month tour of the Zapatistas through all 31 Mexican states to occur concurrently with the electoral campaign starting January 2006.

On June 28, 2005, the EZLN released an installment of what it called the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle. According to the communiqué, the EZLN had reflected on its history and decided that it must change in order to continue its struggle. Accordingly, the EZLN had decided to unite with the "workers, farmers, students, teachers, and employees ... the workers of the city and the countryside". They proposed to do so through a non-electoral front to talk and collectively write a new constitution to establish a new political culture.

On January 1, 2006, the EZLN began a massive tour, "The Other Campaign", encompassing all 31 Mexican states in the buildup to that year's presidential election, which the EZLN made clear they would not participate in directly.

On May 3–4, 2006, a series of demonstrations protested the forcible removal of irregular flower vendors from a lot in Texcoco for the construction of a Walmart branch. The protests turned violent when state police and the Federal Preventive Police bussed in some 5,000 agents to San Salvador Atenco and the surrounding communities. A local organization called the People's Front in Defense of the Land (FPDT), which adheres to the Sixth Declaration, called in support from other regional and national adherent organizations. "Delegate Zero" and his "Other Campaign" were at the time in nearby Mexico City, having just organized May Day events there, and quickly arrived at the scene. The following days were marked by violence, with some 216 arrests, over 30 rape and sexual abuse accusations against the police, five deportations, and one casualty, a 14-year-old boy named Javier Cortes shot by a policeman. A 20-year-old UNAM economics student, Alexis Benhumea, died on the morning of June 7, 2006, after being in a coma caused by a blow to the head from a tear-gas grenade launched by police.[23] Most of the resistance organizing was done by the EZLN and Sixth Declaration adherents, and Delegate Zero stated that the "Other Campaign" tour would be temporarily halted until all prisoners were released.

In late 2006 and early 2007, the Zapatistas (through Subcomandante Marcos), along with other indigenous peoples of the Americas, announced the Intercontinental Indigenous Encounter. They invited indigenous people from throughout the Americas and the rest of the world to gather on October 11–14, 2007, near Guaymas, Sonora. The declaration for the conference designated this date because of "515 years since the invasion of ancient Indigenous territories and the onslaught of the war of conquest, spoils and capitalist exploitation". Comandante David said in an interview, "The object of this meeting is to meet one another and to come to know one another’s pains and sufferings. It is to share our experiences, because each tribe is different."[24]

The Third Encuentro of the Zapatistas People with the People of the World was held from December 28, 2007, through January 1, 2008.[25]

In mid-January 2009, Marcos made a speech on behalf of the Zapatistas in which he supported the resistance of the Palestinians as "the Israeli government's heavily trained and armed military continues its march of death and destruction". He described the actions of the Israeli government as a "classic military war of conquest". He said, "The Palestinian people will also resist and survive and continue struggling and will continue to have sympathy from below for their cause."[26]

2010s

The Zapatistas invited the world to a three-day fiesta to celebrate ten years of Zapatista autonomy in August 2013 in the five caracoles of Chiapas. They expected 1,500 international activists to attend the event, titled the Little School of Liberty.[27][28]

In 2016, at the National Indigenous Congress and the EZLN agreed to select a candidate to represent them in the forthcoming 2018 Mexican general election. This decision broke the Zapatista's two-decade tradition of rejecting Mexican electoral politics. In May 2017, María de Jesús Patricio Martínez was selected to stand, she is Mexican and Nahua.[29][30][31]

Ideology

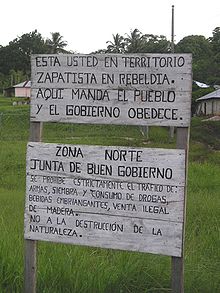

Federal Highway 307, Chiapas. The top sign reads, in Spanish, "You are in Zapatista rebel territory. Here the people command and the government obeys." Bottom sign: "North Zone. Council of Good Government. Trafficking in weapons, planting of drugs, drug use, alcoholic beverages, and illegal selling of wood are strictly prohibited. No to the destruction of nature."

The ideology of the Zapatista movement, Neozapatismo, synthesizes Mayan tradition with elements of libertarian socialism, anarchism,[32][33] and Marxism.[34] The historical influence of Mexican anarchists and various Latin American socialists is apparent in Neozapatismo. The positions of Subcomandante Marcos add a Marxist[35] element to the movement. A Zapatista slogan is in harmony with the concept of mutual aid: "For everyone, everything. For us, nothing" (Para todos todo, para nosotros nada).

The EZLN opposes economic globalization, arguing that it severely and negatively affects the peasant life of its indigenous support base and oppressed people worldwide. The signing of NAFTA also resulted in the removal of Article 27, Section VII, from the Mexican Constitution, which had guaranteed land reparations to indigenous groups throughout Mexico.

Another key element of the Zapatistas' ideology is their aspiration to do politics in a new, participatory way, from the "bottom up" instead of "top down". The Zapatistas consider the contemporary political system of Mexico inherently flawed due to what they consider its purely representative nature and its disconnection from the people and their needs. In contrast, the EZLN aims to reinforce the idea of participatory democracy or radical democracy by limiting public servants' terms to only two weeks, not using visible organization leaders, and constantly referring to the people they are governing for major decisions, strategies, and conceptual visions. Marcos has reiterated, "my real commander is the people". In accordance with this principle, the Zapatistas are not a political party: they do not seek office throughout the state, because that would perpetuate the political system by attempting to gain power within its ranks. Instead, they wish to reconceptualize the entire system.

Women's Revolutionary Law

From the First Declaration from the Lacandon Jungle, the Zapatistas presented to the people of Mexico, the government, and the world their Revolutionary Laws on January 1, 1994. One of the laws was the Women's Revolutionary Law,[36] which states:

- Women, regardless of their race, creed, color or political affiliation, have the right to participate in the revolutionary struggle in any way that their desire and capacity determine.

- Women have the right to work and receive a fair salary.

- Women have the right to decide the number of children they have and care for.

- Women have the right to participate in the matters of the community and hold office if they are free and democratically elected.

- Women and their children have the right to Primary Attention in their health and nutrition.

- Women have the right to an education.

- Women have the right to choose their partner and are not obliged to enter into marriage.

- Women have the right to be free of violence from both relatives and strangers.

- Women will be able to occupy positions of leadership in the organization and hold military ranks in the revolutionary armed forces.

- Women will have all the rights and obligations elaborated in the Revolutionary Laws and regulations.

Postcolonial gaze

The Zapatistas' response to the introduction of NAFTA in 1994, it is argued, reflects the shift in perception taking place in societies that have experienced colonialism.[37] The theory of "postcolonial gaze" studies what is described as the cultural and political impacts of colonization on formerly colonized societies and how these societies overcome centuries of discrimination and marginalization by colonialists and their descendents.[38] In Mexico, the theory of the postcolonial gaze is being fostered predominantly in areas of large indigenous populations and marginalization, like Chiapas. Over the last 20 years, Chiapas is said to have emerged as a formidable force against the Mexican government, fighting against structural violence and social and economic marginalization brought on by globalization.[39] The Zapatista rebellion not only raised many questions about the consequences of globalization and free trade; it also questioned the long-standing ideas created by the Spanish colonial system. Postcolonialism is the antithesis of imperialism because it attempts to explain how the prejudices and restrictions created by colonialism are being overcome.[38] This is especially obvious in countries that have large social and economic inequalities, where colonial ideas are deeply entrenched in the minds of the colonials' descendents.

An early example of the Zapatistas' effective use of the postcolonial gaze was their use of organizations like the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) to raise of awareness for their rebellion and indigenous rights, what critics described as the Mexican government's lack of respect for the country's impoverished and marginalized populations.[40] Appealing to the ECOSOC and other traditionally Western-influenced non-governmental bodies allowed the Zapatistas, it is argued, to establish a sense of autonomy by using the postcolonial gaze to redefine their identities both as indigenous people and as citizens of Mexico.[41]

Communications

Wearing a headset. "Marcha del Color de la Tierra" (2001).

From the beginning, the EZLN has made communication with the rest of Mexico and the world a high priority. The EZLN has used technology, including cellular phones and the Internet, to generate international solidarity with sympathetic people and organizations. Rap-rock band Rage Against the Machine is well known for its support of the EZLN, using the red star symbol as a backdrop to their live shows and often informing concert crowds of the ongoing situation.

The Zapatista flag in the background; RATM on stage.

As a result, on trips abroad, the president of Mexico is routinely confronted by small activist groups about "the Chiapas situation". The Zapatistas are featured prominently in Rage Against the Machine's songs, in particular "People of the Sun", "Wind Below", "Zapata's Blood", and "War Within a Breath".[42] Another band that has openly supported the EZLN's cause is Los de Abajo.

Before 2001, Marcos' writings were often published in some Mexican and a few international newspapers. Then Marcos fell silent, and his relationship with the media declined. When he resumed writing in 2002, he assumed a more aggressive tone, and his attacks on former allies angered some of the EZLN's supporters. Except for these letters and occasional critical communiqués about the political climate, the EZLN was largely silent until August 2003, when Radio Insurgente was launched from an unknown location.

In mid-2004, COCOPA head Luis H. Álvarez stated that Marcos had not been seen in Chiapas for some time. The EZLN received little press coverage during this time, although it continued to develop the local governments it had created earlier. In August, Marcos sent eight brief communiqués to the Mexican press, published from August 20 through 28. The series was entitled Reading a Video (possibly mocking political video scandals that occurred earlier that year). It began and ended as a kind of written description of an imaginary low-budget Zapatista video, with the rest being Marcos' comments on political events of the year and the EZLN's current stance and development.

In 2005, Marcos made headlines again by comparing the then presidential candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador to Carlos Salinas de Gortari (as part of a broad criticism of the three main political parties in Mexico, the PAN, PRI, and PRD), and publicly declaring the EZLN in "Red Alert". Shortly thereafter, communiqués announced that the EZLN had undergone a restructuring that enabled them to withstand the loss of their public leadership (Marcos and the CCRI). After consulting with their support base, the Zapatistas issued the Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.

Since the Zapatistas' first uprising, the newspaper La Jornada has continuously covered them. Most communiqués and many of Marcos's letters are delivered to and only published by La Jornada, and the online edition of the newspaper has a section dedicated to The Other Campaign.

The independent media organization Indymedia also covers and prints Zapatista developments and communications.

Horizontal autonomy and indigenous leadership

Zapatista Chiapas

See also: Rebel Autonomous Zapatista Municipalities

Zapatista communities continue to practice horizontal autonomy and mutual aid by building and maintaining their own health, education, and sustainable agro-ecological systems, promoting equitable gender relations via Women's Revolutionary Law, and building international solidarity through humble outreach and non-imposing political communication. In addition to their focus on building "a world where many worlds fit", the Zapatistas continue to resist periodic attacks. The Zapatista struggle re-gained international attention in May 2014 with the death of teacher and education promoter Galeano, who was murdered in an attack on a Zapatista school and health clinic led by 15 local paramilitaries.[43] In the weeks that followed, thousands of Zapatistas and national and international sympathizers mobilized and gathered to honor Galeano. This event also saw the famed and enigmatic unofficial spokesperson of the Zapatistas, Subcomandante Marcos, announce that he would be stepping down,[44] which symbolized a shift in the EZLN to completely Indigenous leadership.

Notable members

Artistic expression inspired by Comandanta Ramona.

- Subcomandante Insurgente Galeano, previously known as Subcomandante Marcos

- Comandanta Ramona

- Subcomandante Elisa

- Comandanta Esther

- Subcomandante Moisés

In popular culture

- Rap metal group Rage Against the Machine's 1996 single "People of the Sun" is about the Zapatista uprising and features footage of Zapatistas in its music video. The group also incorporates the Zapatista flag in its concerts (lead singer Zack de la Rocha's grandfather fought in the Mexican Revolution, and de la Rocha saw this struggle reflected in the Zapatistas).

- Indie rock group Swirlies' song "San Cristobal de las Casas" featured on their 1995 EP and 1996 album, is about the Zapatista uprising and paramilitary backlash.

- Franco-Spanish songwriter Manu Chao performed a song for the EZLN on his 2002 live album, Radio Bemba Sound System.

- Spanish ska group Ska-P's 1998 song Paramilitar references the EZLN.

See also

- Rebel Autonomous Zapatista Municipalities

A Place Called Chiapas, a documentary on the Zapatistas and Subcomandante Marcos.- Chiapas conflict

Himno Zapatista, anthem of the Zapatistas- Popular Revolutionary Army

- Index of Mexico-related articles

- Indigenous movements in the Americas

- Indigenous peoples of Mexico

- Mexican Indignados Movement

- San Andrés Accords

- Zapatismo

- Zapatista coffee cooperatives

- Women in the EZLN

References

Footnotes

^ "A brief history of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation". ROAR Magazine. Retrieved 2016-11-13..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Gahman, Levi: Zapatistas Begin a New Cycle of Building Indigenous Autonomy http://www.cipamericas.org/archives/12372/

^ Baspineiro, Alex Contreras. "The Mysterious Silence of the Mexican Zapatistas." Narco News (May 7, 2004).

^ "The EZLN is NOT Anarchist - A Zapatista Response Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine."

^ "A Commune in Chiapas? Mexico and the Zapatista Rebellion"

^ Mazarr, Michael J. (2002). Information Technology and World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-230-10922-3.

^ SIPAZ, International Service for Peace webisite, "1994" Archived November 17, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

^ ab Olesen, Thomas (2006). Latin American Social Movements. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. p. 187.

^ "Rising Inequality in Mexico: Returns to Household Characteristics and the 'Chiapas Effect' by César P. Bouillon, Arianna Legovini, Nora Lustig :: SSRN". Papers.ssrn.com. 1999-11-01. doi:10.2139/ssrn.182178. SSRN 182178.

^ O'Neil et al. 2006, p. 377.

^ Manaut, Raúúl Beníítez; Selee, Andrew; Arnson, Cynthia J. (2006-02-01). "Frozen Negotiations: The Peace Process in Chiapas". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 22 (1): 131–152. doi:10.1525/msem.2006.22.1.131. ISSN 0742-9797.

^ "«La Jornada: mayo 4 de 1996»". unam.mx. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

^ «U.S. military aids Mexico's attacks on Zapatistas»

^ «Sedena sabía de la guerrilla chiapaneca desde 1985» Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

^ «Ganaderos e indígenas hablan de grupos guerrilleros»

^ «Salinas recibió informes sobre Chiapas, desde julio del 93»

^ Jornada, La. "A 15 años de relaciones entre México y el Vaticano - La Jornada". www.jornada.unam.mx. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

^ México, El Universal, Compañia Periodística Nacional. "El Universal - Opinion - Renuncia en Gobernación". www.eluniversalmas.com.mx. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

^ «Tampico la conexión zapatista» Archived November 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

^ «Marcos en la mira de Zedillo» Archived October 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

^ O'Neil et al. 2006, p. 378.

^ Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle on Wikisource

^ Alcántara, Liliana. "Dan el último adiós a Alexis Benhumea". El Universal. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

^ Norrell, Brenda. "Zapatistas Select Yaqui to Host Intercontinental Summit in Mexico". Narco News (May 7, 2007).

^ http://zeztainternazional.ezln.org.mx/ 2008.

^ "Zapatista Commander: Gaza Will Survive" Archived January 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Palestine Chronicle

^ Leonidas Oikonomakis on August 6, 2013 Zapatistas celebrate 10 years of autonomy with ‘escuelita’ http://roarmag.org/2013/08/escuelita-zapatista-10-year-autonomy/

^ "the Little School of Liberty according to the Zapatistas" http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/2013/08/04/votan-iv-dia-menos-7/

^ "Zapatistas Meet to Elect First Indigenous Presidential Candidate". TeleSUR. May 27, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

^ "Dismantling Power: The Zapatista Indigenous Presidential Candidate's Vision to Transform Mexico from Below". counterpunch.org. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

^ Fitzwater, Dylan Eldredge. "Zapatistas and Indigenous Congress Seek to Revolutionize Mexico's 2018 Election". Truthout. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

^ "Morgan Rodgers Gibson (2009) 'The Role of Anarchism in Contemporary Anti-Systemic Social Movements', Website of Abahlali Mjondolo, December, 2009". Abahlali.org. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

^ "Morgan Rodgers Gibson (2010) 'Anarchism, the State and the Praxis of Contemporary Antisystemic Social Movements, December, 2010". Abahlali.org. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

^ "The Zapatista Effect: Information Communication Technology Activism and Marginalized Communities Archived August 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine."

^ "The Zapatista's Return: A Masked Marxist on the Stump"

^ "EZLN—Women's Revolutionary Law". Flag.blackened.net. Retrieved 2013-10-29.

^ Beardsell, Peter (2000). Europe and Latin America: Returning the Gaze. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

^ ab Lunga, Victoria (2008). "Postcolonial Theory: A Language for a Critique of Globalization". Perspectives on Global Development and Technology. 7 (3/4): 191–199. doi:10.1163/156914908x371349.

^ Collier, George (2003). A Generation of Crisis in the Central Highlands of Chiapas. Rowmand and Littlefield Publishers Inc. p. 33.

^ Jung, Courtney (2003). "The Politics of Indigenous Identity, Neoliberalism, Cultural Rights, and the Mexican Zapatistas". JSTOR 40971622.

^ Hiddleston, Jane (2009). Understanding Movements in Modern Thought: Understanding Postcolonialism. Durham, UK: Acumen.

^ Rosalva Bermudez-Ballin, Interview with Zach la Rocha (Rage Against The Machine), Nuevo Amanecer Press (via spunk.org), 8 Jul 1998

^ Gahman, Levi - Death of a Zapatista http://rabble.ca/news/2014/06/death-zapatista-neoliberalisms-assault-on-indigenous-autonomy/

^ "Mexico's Zapatista rebel leader Subcomandante Marcos steps down". BBC. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

Bibliography

Collier, George A. (2008). Basta!: Land and the Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas (3rd. ed.). Food First Books. ISBN 978-0-935028-97-3.

- (Ed.) Ponce de Leon, J. (2001). Our Word Is Our Weapon: Selected Writings, Subcomandante Marcos. New York: Seven Stories Press.

ISBN 1-58322-036-4.

Harvey, Neil (1998). The Chiapas Rebellion: The Struggle for Land and Democracy. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2238-2.

O'Neil, Patrick H.; Fields, Karl; Share, Don (2006). Cases in Comparative Politics (2nd ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-92943-4.

- Conant, J. (2010). A Poetics of Resistance: The Revolutionary Public Relations of the Zapatista Insurgency. Oakland: AK Press.

ISBN 978-1-849350-00-6. - Klein, H. (2015). Compañeras: Zapatista Women's Stories. New York: Seven Stories Press.

ISBN 978-1-60980-587-6.

Further reading

- Castellanos, L. (2007). México Armado: 1943-1981. Epilogue and chronology by Alejandro Jiménez Martín del Campo. México: Biblioteca ERA. 383 pp.

ISBN 968-411-695-0

ISBN 978-968-411-695-5

- Patrick & Ballesteros Corona, Carolina (1998). Cuninghame, "The Zapatistas and Autonomy", Capital & Class, No. 66, Autumn, pp 12–22.

- The Zapatista Reader edited by Tom Hayden 2002 A wide sampling of notable writing on the subject.

ISBN 9781560253358

Klein, Hilary. (2015) Compañeras: Zapatista Women's Stories. Seven Stories Press.

ISBN 9781609805876

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zapatista Army of National Liberation. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Zapatista Army of National Liberation |

Official website (in Spanish)

- Schools for Chiapas

EZLN Communiques (1994–2004) translated into English

Our Word Is Our Weapon by Subcomandante Marcos Chapter 1- "What is it that is Different About the Zapatistas?"

Zapatista by Blake Bailey- A Celebration of the Struggle of the Zapatista Women

- Occupy Movement, the Zapatistas and the General Assemblies

The Narco News Bulletin - Articles on the Zapatistas

"A Commune in Chiapas? Mexico and the Zapatista Rebellion (1994–2000)" by LibCom.org

"Visiting the Zapatistas" by Nick Rider, New Statesman, March 12, 2009

"Commodifying the Revolution: Zapatista Villages Become Hot Tourist Destinations" by John Ross

A Glimpse Into the Zapatista Movement, Two Decades Later by Laura Gottesdiener. The Nation, January 23, 2014.

We All Must Become Zapatistas (2014.06.02), Chris Hedges, Truthdig