Stewart Brand

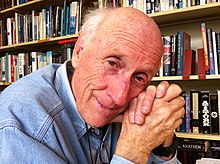

Stewart Brand | |

|---|---|

Brand at home in California, December 2010 | |

| Born | (1938-12-14) December 14, 1938 Rockford, Illinois, United States |

| Occupation | Writer, editor, entrepreneur |

| Known for | Whole Earth Catalog The WELL Long Now Foundation |

| Spouse(s) | Lois Jennings (1966–1973) Ryan Phelan (1983–present)[1] |

| Website | sb.longnow.org |

Stewart Brand (born December 14, 1938) is an American writer, best known as editor of the Whole Earth Catalog. He founded a number of organizations, including The WELL, the Global Business Network, and the Long Now Foundation. He is the author of several books, most recently Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto.

Contents

1 Life

2 Merry Pranksters

3 NASA images of Earth

4 Douglas Engelbart

5 Whole Earth Catalog

6 CoEvolution Quarterly

7 California government

8 The WELL

9 Global Business Network

10 Whole Earth Discipline

11 The Long Now Foundation

12 Works

13 Publications

13.1 Books

13.2 As editor or as co-editor

14 See also

15 References

16 Further reading

17 External links

Life

Brand attended Phillips Exeter Academy. He studied biology at Stanford University, graduating in 1960. In 1966, he married mathematician Lois Jennings, an Ottawa Native American.[2] As a soldier in the U.S. Army, he was a parachutist and taught infantry skills; he later expressed the view that his experience in the military had fostered his competence in organizing.[3] A civilian again in 1962, he studied design at San Francisco Art Institute, photography at San Francisco State College, and participated in a legitimate scientific study of then-legal LSD, in Menlo Park, California.

Brand has lived in California since the 1960s. He and his second wife live on Mirene, a 64-foot (20 m)-long working tugboat. Built in 1912, the boat is moored in a former shipyard in Sausalito, California.[4] He works in Mary Heartline, a grounded fishing boat about 100 yards (90 metres) away.[4] A favorite item of his is a table on which Otis Redding is said to have written "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay". (Brand acquired it from an antiques dealer in Sausalito.)[4]

Merry Pranksters

By the mid-1960s, Brand became associated with author Ken Kesey and the "Merry Pranksters". With his partner Ramón Sender Barayón, he produced the Trips Festival in San Francisco, an early effort involving rock music and light shows. This was one of the first venues at which the Grateful Dead performed in San Francisco. About 10,000 hippies attended, and Haight-Ashbury soon emerged as a community.[5]Tom Wolfe describes Brand in the beginning of his 1968 book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

NASA images of Earth

Earth from space, by ATS-3 satellite, 1967.

Earthrise, by William Anders, Apollo 8, 1968.

In 1966, Brand campaigned to have NASA release the then-rumored satellite image of the entire Earth as seen from space. He sold and distributed buttons for 25 cents each[6] asking, "Why haven't we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?".[7] During this campaign, Brand met Richard Buckminster Fuller, who offered to help Brand with his projects.[8] In 1967, a satellite, ATS-3, took the photo. Brand thought the image of our planet would be a powerful symbol. It adorned the first (Fall 1968) edition of the Whole Earth Catalog.[9] Later in 1968, a NASA astronaut took an Earth photo,[7]Earthrise, from Moon orbit, which became the front image of the spring 1969 edition of the Catalog. 1970 saw the first celebration of Earth Day.[6] During a 2003 interview, Brand explained that the image "gave the sense that Earth's an island, surrounded by a lot of inhospitable space. And it's so graphic, this little blue, white, green and brown jewel-like icon amongst a quite featureless black vacuum."

Douglas Engelbart

In late 1968, Brand assisted electrical engineer Douglas Engelbart with The Mother of All Demos, a famous presentation of many revolutionary computer technologies (including hypertext, email, and the mouse) to the Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco.[10]

Brand surmised that given the necessary consciousness, information, and tools, human beings could reshape the world they had made (and were making) for themselves into something environmentally and socially sustainable.[11]

Whole Earth Catalog

During the late 1960s and early 1970s about 10 million Americans were involved in living communally.[12] In 1968, using the most basic approaches to typesetting and page-layout, Brand and his colleagues created issue number one of The Whole Earth Catalog, employing the significant subtitle, "access to tools".[11] Brand and his wife Lois travelled to communes in a 1963 Dodge truck known as the Whole Earth Truck Store, which moved to a storefront in Menlo Park, California.[11] That first oversize Catalog, and its successors in the 1970s and later, reckoned a wide assortment of things could serve as useful "tools": books, maps, garden implements, specialized clothing, carpenters' and masons' tools, forestry gear, tents, welding equipment, professional journals, early synthesizers, and personal computers. Brand invited "reviews" (written in the form of a letter to a friend) of the best of these items from experts in specific fields. The information also described where these things could be located or purchased. The Catalog's publication coincided with the great wave of social and cultural experimentation, convention-breaking, and "do it yourself" attitude associated with the "counterculture".

The influence of these Whole Earth Catalogs on the rural back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s, and the communities movement within many cities, was widespread throughout the United States, Canada, and Australia. A 1972 edition sold 1.5 million copies, winning the first U.S. National Book Award in category Contemporary Affairs.[13]

CoEvolution Quarterly

To continue this work and also to publish full-length articles on specific topics in the natural sciences and invention, in numerous areas of the arts and the social sciences, and on the contemporary scene in general, Brand founded the CoEvolution Quarterly (CQ) during 1974, aimed primarily at educated laypersons. Brand never better revealed his opinions and reason for hope than when he ran, in CoEvolution Quarterly #4, a transcription of technology historian Lewis Mumford's talk "The Next Transformation of Man", in which he stated that "man has still within him sufficient resources to alter the direction of modern civilization, for we then need no longer regard man as the passive victim of his own irreversible technological development."

The content of CoEvolution Quarterly often included futurism or risqué topics. Besides giving space to unknown writers with something valuable to say, Brand presented articles by many respected authors and thinkers, including Lewis Mumford, Howard T. Odum, Witold Rybczynski, Karl Hess, Orville Schell, Ivan Illich, Wendell Berry, Ursula K. Le Guin, Gregory Bateson, Amory Lovins, Hazel Henderson, Gary Snyder, Lynn Margulis, Eric Drexler, Gerard K. O'Neill, Peter Calthorpe, Sim Van der Ryn, Paul Hawken, John Todd, Kevin Kelly, and Donella Meadows. During ensuing years, Brand authored and edited a number of books on topics as diverse as computer-based media, the life history of buildings, and ideas about space colonies.

He founded the Whole Earth Software Review, a supplement to the Whole Earth Software Catalog, in 1984. It merged with CoEvolution Quarterly to form the Whole Earth Review in 1985.

California government

From 1977 to 1979, Brand served as "special adviser" to the administration of California Governor Jerry Brown.

The WELL

In 1985, Brand and Larry Brilliant founded The WELL ("Whole Earth 'Lectronic Link"), a prototypical, wide-ranging online community for intelligent, informed participants the world over.[14] The WELL won the 1990 Best Online Publication Award from the Computer Press Association.[15] Almost certainly the ideas behind the WELL were greatly inspired by Douglas Engelbart's work at SRI International; Brand was acknowledged by Engelbart in "The Mother of All Demos" in 1968 when the computer mouse and video conferencing were introduced.[16]

Global Business Network

Brand listening in Sausalito, California, in 2009.

During 1986, Brand was a visiting scientist at the MIT Media Lab. Soon after, he became a private-conference organizer for such corporations as Royal Dutch/Shell, Volvo, and AT&T Corporation. In 1988, he became a co‑founder of the Global Business Network, which explores global futures and business strategies informed by the sorts of values and information which Brand has always found vital. The GBN has become involved with the evolution and application of scenario thinking, planning, and complementary strategic tools. In other connections, Brand has been part of the board of the Santa Fe Institute (founded in 1984), an organization devoted to "fostering a multidisciplinary scientific research community pursuing frontier science". He has also continued to promote the preservation of tracts of wilderness.

Whole Earth Discipline

The Whole Earth Catalog implied an ideal of human progress that depended on decentralized, personal, and liberating technological development—so‑called "soft technology". However, during 2005 he criticized aspects of the international environmental ideology he had helped to develop. He wrote an article called "Environmental Heresies"[17] in the May 2005 issue of the MIT Technology Review, in which he describes what he considers necessary changes to environmentalism. He suggested among other things that environmentalists embrace nuclear power and genetically modified organisms as technologies with more promise than risk.

Brand later developed these ideas into a book and published the Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto in 2009. The book examines how urbanization, nuclear power, genetic engineering, geoengineering, and wildlife restoration can be used as powerful tools in humanity's ongoing fight against global warming.[18]

The Long Now Foundation

Brand is co‑chair and President of the Board of Directors of The Long Now Foundation. Brand chairs the foundation's Seminars About Long-term Thinking (SALT). This series on long-term thinking has presented a large range of different speakers including: Brian Eno, Neal Stephenson, Vernor Vinge, Philip Rosedale, Jimmy Wales, Kevin Kelly, Clay Shirky, Ray Kurzweil, Bruce Sterling, Cory Doctorow, and many others.

Works

Stewart Brand is the initiator or was involved with the development of the following:

The Whole Earth Catalog in 1968

CoEvolution Quarterly in 1974

The Whole Earth Software Catalog and Review in 1984

Whole Earth Review in 1985- Point Foundation

Global Business Network (co-founder)

The WELL in 1985, with Larry Brilliant

The Hackers Conference in 1984

Long Now Foundation in 1996, with computer scientist Danny Hillis—one of the Foundation's projects is to build a 10,000 year clock, the Clock of the Long Now

New Games Tournament (was involved initially, but left the project)- In April 2015, Brand joined with a group of scholars in issuing An Ecomodernist Manifesto.[19][20] The other authors were: John Asafu-Adjaye, Linus Blomqvist, Barry Brook. Ruth DeFries, Erle Ellis, Christopher Foreman, David Keith, Martin Lewis, Mark Lynas, Ted Nordhaus, Roger A. Pielke, Jr., Rachel Pritzker, Joyashree Roy, Mark Sagoff, Michael Shellenberger, Robert Stone, and Peter Teague[21]

Publications

Books

II Cybernetic Frontiers, 1974, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-394-49283-8 (hardcover),

ISBN 0-394-70689-7 (paperback)

The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT, 1987,

ISBN 0-670-81442-3 (hardcover); 1988,

ISBN 0-14-009701-5 (paperback)

How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They're Built, 1994.

ISBN 0-670-83515-3

The Clock of the Long Now: Time and Responsibility, 1999.

ISBN 0-465-04512-X

Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto, Viking Adult, 2009.

ISBN 0-670-02121-0

As editor or as co-editor

The Whole Earth Catalog, 1968–72 (original editor, winner of the National Book Award, 1972)

Last Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools, 1971

Whole Earth Epilog: Access to Tools, 1974,

ISBN 0-14-003950-3

The (Updated) Last Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools, 16th edition, 1975,

ISBN 0-14-003544-3

Space Colonies, Whole Earth Catalog, 1977,

ISBN 0-14-004805-7

- As co-editor with J. Baldwin: Soft-Tech, 1978,

ISBN 0-14-004806-5

The Next Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools, 1980,

ISBN 0-394-73951-5;

The Next Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools, revised 2nd edition, 1981,

ISBN 0-394-70776-1

- As editor-in-chief: Whole Earth Software Catalog, 1984,

ISBN 0-385-19166-9

- As editor-in-chief: Whole Earth Software Catalog for 1986, "2.0 edition" of above title, 1985,

ISBN 0-385-23301-9

- As co-editor with Art Kleiner: News That Stayed News, 1974–1984: Ten Years of CoEvolution Quarterly, 1986,

ISBN 0-86547-201-7 (hardcover),

ISBN 0-86547-202-5 (paperback)

Introduction by Brand: The Essential Whole Earth Catalog: Access to Tools and Ideas (Introduction by Brand), 1986,

ISBN 0-385-23641-7

Foreword by Brand: Signal: Communication Tools for the Information Age, editor: Kevin Kelly, 1988,

ISBN 0-517-57084-X

- Foreword by Brand: The Fringes of Reason: A Whole Earth Catalog, editor: Ted Schultz, 1989,

ISBN 0-517-57165-X

- Foreword by Brand: Whole Earth Ecolog: The Best of Environmental Tools & Ideas, editor: J. Baldwin, 1990,

ISBN 0-517-57658-9

See also

- Neo-environmentalism

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

- Phil Garlington, "Stewart Brand," Outside magazine, December 1977.

- Sam Martin and Matt Scanlon, "The Long Now: An Interview with Stewart Brand," Mother Earth News magazine, January 2001[22]

- "Stewart Brand" (c.v., last updated September 2006)[23]

- Massive Change Radio interview with Stewart Brand, November 2003[24]

Whole Earth Catalog, various issues, 1968–1998.

CoEvolution Quarterly (in the 1980s, renamed Whole Earth Review, later just Whole Earth), various issues, 1974–2002.

^ "Bio..." Retrieved 2014-05-20.

^ Brand 2009, p. 236

^ Stewart Brand. "Big Think Interview With Stewart Brand - Big Think". Big Think.

^ abc Lewine, Edward (April 19, 2009). "On the Waterfront". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

^ Brand, Stewart. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: The Legacy of the Whole Earth Catalog. Stanford University Libraries via Google. Event occurs at 32:30. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

^ ab Brand, Stewart. "Photography changes our relationship to our planet". Smithsonian Photography Initiative. Archived from the original on 2008-05-30. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

^ ab Brand 2009, p. 214

^ Leonard, Jennifer. "Stewart Brand on the long view". Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

^ The front cover of the Fall 1968 edition of the Whole Earth Catalog showing the AST-3 image of 10 November 1967

^ Fisher, Adam (9 December 2018). "How Doug Engelbart Pulled off the Mother of All Demos". Wired. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

^ abc Kirk, Andrew G. (2007). Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism. KSBW. University Press of Kansas via Amazon.com. p. 42. ISBN 0-7006-1545-8.

Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "Kirk" defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

^ Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: The Legacy of the Whole Earth Catalog. Stanford University Libraries via Google. Event occurs at 19:00. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

^

"National Book Awards – 1972". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-09.

There was a "Contemporary" or "Current" award category from 1972 to 1980.

^ Fred., Turner, (2006). From counterculture to cyberculture : Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226817415. OCLC 62533774.

^ Katie Hafner, The WELL: A Story of Love, Death and Real Life in the Seminal Online Community:(2001) Carroll & Graf Publishers

ISBN 0-7867-0846-8

^ "(5:26:00)". Youtube.com. 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2011-10-29.

^ "Environmental Heresies". MIT Technology Review.

^ Stewart Brand (2009). Whole Earth Discipline: An Ecopragmatist Manifesto. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02121-5.

^ "An Ecomodernist Manifesto". ecomodernism.org. Retrieved April 17, 2015.A good Anthropocene demands that humans use their growing social, economic, and technological powers to make life better for people, stabilize the climate, and protect the natural world.

^ Eduardo Porter (April 14, 2015). "A Call to Look Past Sustainable Development". The New York Times. Retrieved April 17, 2015.On Tuesday, a group of scholars involved in the environmental debate, including Professor Roy and Professor Brook, Ruth DeFries of Columbia University, and Michael Shellenberger and Ted Nordhaus of the Breakthrough Institute in Oakland, Calif., issued what they are calling the "Eco-modernist Manifesto."

^ "Authors An Ecomodernist Manifesto". ecomodernism.org. Retrieved April 17, 2015.As scholars, scientists, campaigners, and citizens, we write with the conviction that knowledge and technology, applied with wisdom, might allow for a good, or even great, Anthropocene.

^ [1][dead link]

^ "Bio". sb.longnow.org.

^ PDF Archived May 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Binkley, Sam. Getting Loose: Lifestyle Consumption in the 1970s. Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Brokaw, Tom. "Stewart Brand." BOOM! Voices of the Sixties. New York: Random House, 2007.- Kirk, Andrew G. Counterculture Green: The Whole Earth Catalog and American Environmentalism. Lawrence: Univ. of Kansas Press, 2007.

Markoff, John. What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. New York: Penguin, 2005.

Turner, Fred From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. University of Chicago Press. 2006. ISBN 0-226-81741-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stewart Brand. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Stewart Brand |

- Official website

Works by or about Stewart Brand in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Works by Stewart Brand at Open Library

Stewart Brand at TED

Stewart Brand Papers housed at Stanford University Libraries

Appearances on C-SPAN