Timothy Leary

Timothy Leary | |

|---|---|

1989 photo | |

| Born | Timothy Francis Leary (1920-10-22)October 22, 1920 Springfield, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 31, 1996(1996-05-31) (aged 75) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation | Psychologist, writer |

| Employer |

|

| Known for | Psychedelic therapy |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

Arts

Psychedelic film

|

Culture

|

Drugs

|

Experience

|

History

|

Law

|

Related topics

|

|

Timothy Francis Leary (October 22, 1920 – May 31, 1996) was an American psychologist and writer known for advocating the exploration of the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs under controlled conditions.

As a clinical psychologist at Harvard University, Leary conducted experiments under the Harvard Psilocybin Project in 1960–62 (LSD and psilocybin were still legal in the United States at the time), resulting in the Concord Prison Experiment and the Marsh Chapel Experiment. The scientific legitimacy and ethics of his research were questioned by other Harvard faculty because he took psychedelics together with research subjects and pressured students in his class to take psychedelics in the research studies.[1][2][3] Leary and his colleague, Richard Alpert (who later became known as Ram Dass), were fired from Harvard University in May 1963.[4] National illumination as to the effects of psychedelics did not occur until after the Harvard scandal.[5]

Leary believed that LSD showed potential for therapeutic use in psychiatry. He used LSD himself and developed a philosophy of mind expansion and personal truth through LSD.[6][7] After leaving Harvard, he continued to publicly promote the use of psychedelic drugs and became a well-known figure of the counterculture of the 1960s. He popularized catchphrases that promoted his philosophy, such as "turn on, tune in, drop out", "set and setting", and "think for yourself and question authority". He also wrote and spoke frequently about transhumanist concepts involving space migration, intelligence increase, and life extension (SMI²LE),[8] and developed the eight-circuit model of consciousness in his book Exo-Psychology (1977). He gave lectures, occasionally billing himself as a "performing philosopher".[9]

During the 1960s and 1970s, he was arrested often enough to see the inside of 36 prisons worldwide.[10] President Richard Nixon once described Leary as "the most dangerous man in America".[11]

Contents

1 Early life and education

2 Psychedelic experiments and experiences

2.1 Mexico and Harvard research (1957–1963)

2.1.1 Introduction to psychedelic mushrooms

2.1.2 Concord Prison Experiment

2.1.3 Dissension over studies

2.1.4 Firing of Leary

2.2 Millbrook and psychedelic counterculture (1963–1967)

2.3 Post-Millbrook

3 Legal troubles

4 Last two decades

5 Death

6 Influence

7 In popular culture

7.1 In film

7.2 In music

7.3 In comic books

8 Works

9 See also

10 References

11 Further reading

12 External links

Early life and education

Leary was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, the only child[11] in an Irish Catholic household. His father, Timothy "Tote" Leary, was a dentist who left his wife Abigail Ferris when Leary was 14.[12] He graduated from Classical High School in the western Massachusetts city.[13]

He attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts from September 1938 to June 1940. Under pressure from his father, he then accepted an appointment as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. In the first months as a "plebe", he was given numerous demerits for rule infractions and then got into serious trouble for failing to report infractions by other cadets when on supervisory duty. He was alleged to have gone on a drinking binge and to have failed to "come clean" about it. He was asked by the Honor Committee to resign for violating the Academy's honor code. He refused and was "silenced"—that is, shunned and ignored by his fellow cadets as a tactic to pressure him to resign. He was acquitted by a court-martial, but the silencing measures continued in full force, as well as the onslaught of demerits for small rule infractions. The treatment continued in his sophomore year, and his mother appealed to a family friend, United States Senator David I. Walsh, head of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, who conducted a personal investigation. Behind the scenes, the Honor Committee revised its position and announced that it would abide by the court-martial verdict. Leary then resigned and was honorably discharged by the Army.[14] Almost 50 years later, he said that it was "the only fair trial I've had in a court of law".[15]

To the chagrin of his family, Leary elected to transfer to the University of Alabama in late 1941 because of the institution's expeditious response to his application. He enrolled in the university's ROTC program, maintained top grades, and began to cultivate academic interests in psychology (under the aegis of the Middlebury and Harvard-educated Donald Ramsdell) and biology, but he was expelled a year later for spending a night in the female dormitory, losing his student deferment in the midst of World War II.

Leary was drafted into the United States Army and reported for basic training at Fort Eustis in January 1943. He remained in the non-commissioned track while enrolled in the psychology subsection of the Army Specialized Training Program, including three months of study at Georgetown University and six months at Ohio State University.[16]

With no urgent need for officers at the late juncture in the war, Leary was briefly assigned as a private first class to the Pacific War-bound 2d Combat Cargo Group (which he later characterized as "a suicide command... whose main mission, as far as I could see, was to eliminate the entire civilian branch of American aviation from post-war rivalry") at Syracuse Army Air Base in Mattydale, New York.[17] After a fateful reunion with Ramsdell (who was assigned to Deshon General Hospital in Butler, Pennsylvania as chief psychologist) in Buffalo, New York, he was promptly promoted to corporal and reassigned to his mentor's command as a staff psychometrician.[18] He remained in Deshon's deaf rehabilitation clinic for the remainder of the war. While stationed in Butler, Leary began to court Marianne Busch; they married in April 1945. Leary was formally discharged at the rank of sergeant in January 1946, having earned the Good Conduct Medal, the American Defense Service Medal, the American Campaign Medal, and the World War II Victory Medal.[19]

Following retroactive suspension, Leary was reinstated at the University of Alabama and received credit for his Ohio State psychology coursework. He completed his degree via correspondence courses and graduated on August 23, 1945.

Upon receiving his undergraduate degree, Leary decided to pursue an academic career. In 1946, he received an M.S. in psychology at Washington State University, where he studied under noted educational psychologist Lee Cronbach. His M.S. thesis was a study of the clinical applications of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale.[20]

In 1947, Marianne gave birth to their first child, Susan. A son, Jack, was born two years later. In 1950, Leary received a Ph.D. in clinical psychology from the University of California, Berkeley.[21] Like many social scientists of the postwar epoch, Leary was galvanized by the objectivity of modern physics[clarification needed]; his doctoral dissertation (The Social Dimensions of Personality: Group Structure and Process) approached group therapy as a "psychlotron" from which behavioral characteristics could be derived and quantified in a manner analogous to the periodic table, presaging his later development of the interpersonal circumplex.

The new Ph.D. stayed on in the Bay Area as an assistant clinical professor of medical psychology at the University of California, San Francisco; concurrently, Leary co-founded Kaiser Hospital's psychology department in Oakland, California and maintained a private consultancy.[22][23] In 1952, the Leary family spent a year in Spain, subsisting on a research grant. According to Berkeley colleague Marv Freedman, "Something had been stirred in him in terms of breaking out of being another cog in society..."[24]

Despite his nascent professional success, his marriage was strained by multiple infidelities and mutual alcohol abuse. Marianne eventually committed suicide in 1955, leaving him to raise their son and daughter alone.[11] He described himself during this period as "an anonymous institutional employee who drove to work each morning in a long line of commuter cars and drove home each night and drank martinis ... like several million middle-class, liberal, intellectual robots."[25][26]

From 1954[23] or 1955 to 1958, Leary was director of psychiatric research at the Kaiser Family Foundation.[27] In 1957, Leary's The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality was published and was hailed as the 'most important book on psychotherapy of the year' by the Annual Review of Psychology.[28]

Following the termination of his commodious National Institute of Mental Health research grant (precipitated by his absence from a meeting with a NIMH investigator), Leary and his children relocated to Europe in 1958, where he attempted to write his next book on psychology while subsisting on small grants and insurance policies.[29][30] He was overcome by indigence during an unproductive stay in Florence, and returned to academia in late 1959 as a lecturer in clinical psychology at Harvard University at the behest of Frank Barron (a colleague from Berkeley) and David McClelland. During this period, he resided with his children in nearby Newton, Massachusetts. In addition to his teaching duties, Leary was affiliated with the Harvard Center for Research in Personality under McClelland and oversaw the Harvard Psilocybin Project and concomitant experiments in conjunction with assistant professor Richard Alpert. In 1963, Leary was terminated for failing to give his scheduled class lectures,[31] while he claimed that he had fulfilled his teaching obligations in full. The decision to dismiss him may have been influenced by his role in the popularity of psychedelic substances among Harvard students and faculty members, which were legal at the time.[32]

His work in academic psychology expanded on the research of Harry Stack Sullivan and Karen Horney regarding the importance of interpersonal forces in mental health, focusing on how understanding interpersonal processes might facilitate diagnosing disorders and identifying human personality patterns. Leary's dissertation research culminated in the development of the complex and respected interpersonal circumplex model, published in The Interpersonal Diagnosis of Personality,[33] demonstrating how psychologists could methodically use Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) scores to predict respondents' interpersonal response characteristics, or ways that they might respond to various interpersonal situations. Leary's research was an important harbinger of transactional analysis, directly prefiguring the popular work of Eric Berne.[34][35]

Psychedelic experiments and experiences

Mexico and Harvard research (1957–1963)

Leary at the State University of New York at Buffalo during a lecture tour in 1969.

Introduction to psychedelic mushrooms

On May 13, 1957, Life magazine published an article by R. Gordon Wasson that documented the use of psilocybin mushrooms in religious rites of the indigenous Mazatec people of Mexico.[36] Anthony Russo, a colleague of Leary's, had experimented with psychedelic (or entheogenic) Psilocybe mexicana mushrooms on a trip to Mexico and told Leary about it. In August 1960,[37] Leary traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico with Russo and consumed psilocybin mushrooms for the first time, an experience that drastically altered the course of his life.[38] In 1965, Leary commented that he had "learned more about ... (his) brain and its possibilities ... [and] more about psychology in the five hours after taking these mushrooms than ... in the preceding 15 years of studying and doing research in psychology."[38]

Leary returned from Mexico to Harvard in 1960, and he and his associates (notably Richard Alpert, later known as Ram Dass) began a research program known as the Harvard Psilocybin Project. The goal was to analyze the effects of psilocybin on human subjects (first prisoners, and later Andover Newton Theological Seminary students) from a synthesized version of the drug (which was legal at the time), one of two active compounds found in a wide variety of hallucinogenic mushrooms, including Psilocybe mexicana. The compound in question was produced by a process developed by Albert Hofmann of Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, who was famous for synthesizing LSD.[39]

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg heard about the Harvard research project and asked to join the experiments. Leary was inspired by Ginsberg's enthusiasm, and the two shared an optimism in the benefit of psychedelic substances to help people "turn on" (i.e., discover a higher level of consciousness). Together they began a campaign of introducing intellectuals and artists to psychedelics.[40]

Concord Prison Experiment

Leary argued that psychedelic substances—in proper doses, in a stable setting, and under the guidance of psychologists—could alter behavior in beneficial ways not easily attainable through regular therapy. His research focused on treating alcoholism and reforming criminals. Many of his research subjects told of profound mystical and spiritual experiences which they said permanently and positively altered their lives.[41]

The Concord Prison Experiment was designed to evaluate the effects of psilocybin combined with psychotherapy on rehabilitation of released prisoners, after being guided through the psychedelic experience, or "trips," by Leary and his associates. Thirty-six prisoners were reported to have repented and sworn to give up future criminal activity. The average recidivism rate was 60 percent for American prisoners in general, whereas the recidivism rate for those involved in Leary's project dropped to 20 percent. The experimenters concluded that long-term reduction in overall criminal recidivism rates could be effected with a combination of psilocybin-assisted group psychotherapy (inside the prison) along with a comprehensive post-release follow-up support program modeled on Alcoholics Anonymous.[42][43]

Dissension over studies

Timothy Leary, family, and band at the State University of New York at Buffalo during Leary's 1969 lecture tour.

These conclusions were later contested in a follow-up study on the basis of time differences monitoring the study group vs. the control group, and differences between subjects re-incarcerated for parole violations and those imprisoned for new crimes. The researchers concluded that statistically only a slight improvement could be attributed to psilocybin in contrast to the significant improvement reported by Leary and his colleagues.[44]Rick Doblin suggested that Leary had fallen prey to the Halo Effect, skewing the results and clinical conclusions. Doblin further accused Leary of lacking "a higher standard" or "highest ethical standards in order to regain the trust of regulators". Ralph Metzner rebuked Doblin for these assertions: "In my opinion, the existing accepted standards of honesty and truthfulness are perfectly adequate. We have those standards, not to curry favor with regulators, but because it is the agreement within the scientific community that observations should be reported accurately and completely. There is no proof in any of this re-analysis that Leary unethically manipulated his data."[45][46]

Leary and Alpert founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF) in 1962 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in order to carry out studies in the religious use of psychedelic drugs.[47][48] This was run by Lisa Bieberman (now known as Licia Kuenning),[49] a friend of Leary.[50]The Harvard Crimson described her as a "disciple" who ran a Psychedelic Information Center out of her home and published a national LSD newspaper.[51] That publication was actually Leary and Alpert's journal Psychedelic Review, and Bieberman (a graduate of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, who had volunteered for Leary as a student) was its circulation manager.[52][53] Leary and Alpert's research attracted so much public attention that many who wanted to participate in the experiments had to be turned away due to the high demand. To satisfy the curiosity of those who were turned away, a black market for psychedelics sprang up near the Harvard campus.[3]

Firing of Leary

Other professors in the Harvard Center for Research in Personality raised concerns about the legitimacy and safety of the experiments.[54][1][2] They were concerned with Leary and Alpert's abuse of power over students. Leary and Alpert pressured graduate students to participate in their research who they taught in a class required for the students' degrees. Additionally, Leary and Alpert gave psychedelics to undergraduate students despite the university only allowing graduate students to participate. The legitimacy of their research was questioned because Leary and Albert took psychedelics with the students during the experiments. Also, the selection of research participants was not random sampling. These concerns were then printed in The Harvard Crimson and the publicity that followed resulted in the end of the official experiments, an investigation by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health that was eventually dropped, and the firing of Leary and Alpert.

According to Andrew Weil, Leary was fired for not giving his required lectures, while Alpert was fired for allegedly giving psilocybin to an undergraduate in an off-campus apartment.[3][55] This version is supported by the words of Harvard University president Nathan Marsh Pusey, who released the following statement on May 27, 1963:

On May 6, 1963, the Harvard Corporation voted, because Timothy F. Leary, lecturer on clinical psychology, has failed to keep his classroom appointments and has absented himself from Cambridge without permission, to relieve him from further teaching duty and to terminate his salary as of April 30, 1963.[31]

Millbrook and psychedelic counterculture (1963–1967)

Leary's activities interested siblings Peggy, Billy, and Tommy Hitchcock, heirs to the Mellon fortune, who helped Leary and his associates acquire a rambling 64-room mansion in 1963 on an estate in Millbrook, New York, where they continued their experiments. Peggy Hitchcock was director of the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF)'s New York branch, and her brother Billy rented the estate to IFIF.[56] Leary and Alpert immediately set up a communal group with former Psilocybin Project members at the Hitchcock Estate (commonly known as "Millbrook"), and the IFIF was subsequently disbanded and renamed the Castalia Foundation (after the intellectual colony in Herman Hesse's The Glass Bead Game).[57][58][59] The group's journal was the Psychedelic Review.[58] The core group at Millbrook sought to cultivate the divinity within each person, and often participated in group LSD sessions facilitated by Leary.[58] The Castalia Foundation hosted weekend retreats on the estate where people paid to undergo the psychedelic experience without drugs, through meditation, yoga, and group therapy sessions.[59][60] Leary later wrote:

We saw ourselves as anthropologists from the 21st century inhabiting a time module set somewhere in the dark ages of the 1960s. On this space colony we were attempting to create a new paganism and a new dedication to life as art.[61]

The Millbrook estate was later described by Luc Sante of The New York Times as:

the headquarters of Leary and gang for the better part of five years, a period filled with endless parties, epiphanies and breakdowns, emotional dramas of all sizes, and numerous raids and arrests, many of them on flimsy charges concocted by the local assistant district attorney, G. Gordon Liddy.[62]

Others contest this characterization of the Millbrook estate. For instance, in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe portrays Leary as interested only in research and not in using psychedelics merely for recreational purposes. According to "The Crypt Trip" chapter of Wolfe's book, Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters visited the residence, and received a frosty reception.[63] Leary himself had the flu on their arrival and wasn't able to play host.[64] He later met Ken Kesey and Ken Babbs quietly in his room and promised to remain allies in the years ahead.[65]

In 1964, Leary coauthored a book with Alpert and Ralph Metzner called The Psychedelic Experience based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. In it, they wrote:

A psychedelic experience is a journey to new realms of consciousness. The scope and content of the experience is limitless, but its characteristic features are the transcendence of verbal concepts, of spacetime dimensions, and of the ego or identity. Such experiences of enlarged consciousness can occur in a variety of ways: sensory deprivation, yoga exercises, disciplined meditation, religious or aesthetic ecstasies, or spontaneously. Most recently they have become available to anyone through the ingestion of psychedelic drugs such as LSD, psilocybin, mescaline, DMT, etc. Of course, the drug does not produce the transcendent experience. It merely acts as a chemical key — it opens the mind, frees the nervous system of its ordinary patterns and structures.[66]

Leary married model Birgitte Caroline "Nena" von Schlebrügge in 1964 at Millbrook. Both Nena and her brother Bjorn, known as the "Baron," were friends of the Hitchcocks. D. A. Pennebaker, also a Hitchcock friend, and cinematographer Nicholas Proferes documented the event in the short film You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You.[67]Charles Mingus played piano. The marriage lasted a year before von Schlebrügge divorced Leary in 1965 — she married Indo-Tibetan Buddhist scholar and ex-monk Robert Thurman in 1967 and gave birth to Ganden Thurman that same year. Actress Uma Thurman, her second child, was born in 1970.

Leary met Rosemary Woodruff in 1965 at a New York City art exhibit, and invited her to visit Millbrook.[68][69][70] After moving in with him there, she co-edited the manuscript for Leary's 1966 book Psychedelic Prayers: And Other Meditations with Ralph Metzner and Michael Horowitz.[71] The poems in the book were inspired by the Tao Te Ching, and meant to be used as an aid to LSD trips.[71][72] Woodruff helped Leary prepare for weekend multimedia workshops simulating the psychedelic experience, presented in various cities around the East Coast.[71]

In September 1966, Leary gave an interview to Playboy magazine that became famous. In the interview, Leary claimed, among other things, that LSD could be used to cure homosexuality, telling a story about a lesbian who, according to him, became heterosexual after using the drug.[73][74] He later changed this view to a more liberal stance suggesting that homosexuality was not an illness in need of a cure.[75]

By 1966, recreational drug use, particularly of so-called psychedelic drugs, among America's youth had reached such proportions that serious concerns about the nature of these drugs and the impact their use was having on American culture were expressed in the national press and halls of government. In response to these concerns, Senator Thomas Dodd of Connecticut convened Senate subcommittee hearings in order to try to better understand the drug-use phenomenon, eventually with the intention of "stamping out" such usage through the criminalizing of these drugs. Leary was one of several expert witnesses called to testify at these hearings. In his testimony, Leary asserted that "the challenge of the psychedelic chemicals is not just how to control them, but how to use them."[76] He implored the subcommittee not to criminalize psychedelic drug use, which he felt would only serve to exponentially increase its usage among America's youth while removing the safeguards that controlled "set and setting" provided. When subcommittee member Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts asked Leary if LSD usage was "extremely dangerous," Leary replied, "Sir, the motor car is dangerous if used improperly...Human stupidity and ignorance is the only danger human beings face in this world."[77] To conclude his testimony, Leary suggested that legislation be enacted that would require LSD users to be adults who were competently trained and licensed, so that such individuals could use LSD "for serious purposes, such as spiritual growth, pursuit of knowledge, or their own personal development."[78] He presciently noted that without such licensing, the United States would be faced with "another era of prohibition."[79] Leary's testimony proved ineffective; on October 6, 1966, just months after the subcommittee hearings, LSD was banned in California, and by October 1968 LSD was banned in all states as a result of the passage of the Staggers-Dodd Bill.[80]

In 1966, Folkways Records recorded Leary reading from his book The Psychedelic Experience, and released the album The Psychedelic Experience: Readings from the Book "The Psychedelic Experience. A Manual Based on the Tibetan...".[81]

On September 19, 1966, Leary reorganized the IFIF/Castalia Foundation under the nomenclature of the League for Spiritual Discovery, a religion with LSD as its holy sacrament, in part as an unsuccessful attempt to maintain legal status for the use of LSD and other psychedelics for the religion's adherents, based on a "freedom of religion" argument.[59][60] Leary incorporated the League for Spiritual Discovery as a religious organization in New York State, and their belief structure was based on Leary's mantra: "drop out, turn on, tune in."[59] (The Brotherhood of Eternal Love subsequently considered Leary their spiritual leader, but The Brotherhood did not develop out of International Federation for Internal Freedom.) Nicholas Sand, the clandestine chemist for the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, followed Leary to Millbrook and joined the League for Spiritual Discovery. Sand was designated the "alchemist" of the new religion.[82] At the end of 1966, Nina Graboi, a friend and colleague of Leary's who had spent time with him at Millbrook, became the director of the Center for the League of Spiritual Discovery in Greenwich Village.[83][84] The Center opened in March 1967.[85] Leary and Alpert gave free weekly talks at the center, and other guest speakers included Ralph Metzner and Allen Ginsberg.[83][86] Leary's papers at the New York Public Library include complete records of the International Federation for Internal Freedom (IFIF), the Castalia Foundation, and the League for Spiritual Discovery.[87]

During late 1966 and early 1967, Leary toured college campuses presenting a multimedia performance entitled "The Death of the Mind", attempting an artistic replication of the LSD experience.[57][88] He said that the League for Spiritual Discovery was limited to 360 members and was already at its membership limit, but he encouraged others to form their own psychedelic religions. He published a pamphlet in 1967 called Start Your Own Religion to encourage people to do so.[57]

Leary was invited to attend the January 14, 1967 Human Be-In by Michael Bowen, the primary organizer of the event,[89] a gathering of 30,000 hippies in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. In speaking to the group, Leary coined the famous phrase "Turn on, tune in, drop out." In a 1988 interview with Neil Strauss, he said that this slogan was "given to him" by Marshall McLuhan when the two had lunch in New York City, adding, "Marshall was very much interested in ideas and marketing, and he started singing something like, 'Psychedelics hit the spot / Five hundred micrograms, that's a lot,' to the tune of [the well-known Pepsi 1950s singing commercial]. Then he started going, 'Tune in, turn on, and drop out.'"[90] Though the more popular "turn on, tune in, drop out" became synonymous with Leary, his actual definition with the League for Spiritual Discovery was:

"Drop Out – detach yourself from the external social drama which is as dehydrated and ersatz as TV.

Turn On – find a sacrament which returns you to the temple of God, your own body. Go out of your mind. Get high.

Tune In – be reborn. Drop back in to express it. Start a new sequence of behavior that reflects your vision."[59]

Repeated FBI raids ended the Millbrook era. Leary told author and Prankster Paul Krassner regarding a 1966 raid by Liddy, "He was a government agent entering our bedroom at midnight. We had every right to shoot him. But I've never owned a weapon in my life. I have never had and never will have a gun around."[91]

In November 1967, Leary engaged in a televised debate on drug use with MIT professor Jerry Lettvin.[92]

Post-Millbrook

At the end of 1967, Leary moved to Laguna Beach, California and made many new friends in Hollywood. "When he married his third wife, Rosemary Woodruff, in 1967, the event was directed by Ted Markland of Bonanza. All the guests were on acid."[11]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Leary formulated his eight-circuit model of consciousness in collaboration with writer Brian Barritt, in which he wrote that the human mind and nervous system consisted of seven circuits which produce seven levels of consciousness when activated. This model was first published in his short essay "The Seven Tongues of God". The system was soon expanded to include an eighth circuit in a revised version first published in the 1973 pamphlet "Neurologic", written with Joanna Leary while he was in prison. This eighth-circuit idea was not exhaustively formulated until the publication of Exo-Psychology by Leary and Robert Anton Wilson's Cosmic Trigger in 1977. Wilson contributed to the model after befriending Leary in the early 1970s, and used it as a framework for further exposition in his book Prometheus Rising, among other works.[93]

Leary believed that the first four of these circuits ("the Larval Circuits" or "Terrestrial Circuits") are naturally accessed by most people in their lifetimes, triggered at natural transition points in life such as puberty. The second four circuits ("the Stellar Circuits" or "Extra-Terrestrial Circuits"), Leary wrote, were "evolutionary offshoots" of the first four that would be triggered at transition points which humans might acquire if they evolve. These circuits, according to Leary, would equip humans to encompass life in space, as well as the expansion of consciousness that would be necessary to make further scientific and social progress. Leary suggested that some people may "shift to the latter four gears", i.e., trigger these circuits artificially via consciousness-altering techniques such as meditation and spiritual endeavors such as yoga, or by taking psychedelic drugs specific to each circuit. The feeling of floating and uninhibited motion experienced by users of marijuana is one thing that Leary cited as evidence for the purpose of the "higher" four circuits. In the eight-circuit model of consciousness, a primary theoretical function of the fifth circuit (the first of the four, according to Leary, developed for life in outer space) is to allow humans to become accustomed to life in a zero- or low-gravity environment.[94]

Legal troubles

BNDD agents Don Strange (right) and Howard Safir (left) arrest Leary in 1972.

Leary's first run-in with the law came on December 23, 1965, when Leary was arrested for possession of marijuana.[95][96] Leary took his two children, Jack and Susan, and his girlfriend Rosemary Woodruff to Mexico for an extended stay to write a book. On their return from Mexico to the United States, a US Customs Service official found marijuana in Susan's underwear. They had crossed into Nuevo Laredo, Mexico in the late afternoon and discovered that they would have to wait until morning for the appropriate visa for an extended stay. They decided to cross back into Texas to spend the night, and were on the US-Mexico bridge when Rosemary remembered that she had a small amount of marijuana in her possession. It was impossible to throw it out on the bridge, so Susan put it in her underwear.[97] After taking responsibility for the controlled substance, Leary was convicted of possession under the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 on March 11, 1966, sentenced to 30 years in prison, fined $30,000, and ordered to undergo psychiatric treatment. He appealed the case on the basis that the Marihuana Tax Act was unconstitutional, as it required a degree of self-incrimination in blatant violation of the Fifth Amendment.

On December 26, 1968, Leary was arrested again in Laguna Beach, California, this time for the possession of two marijuana "roaches". Leary alleged that they were planted by the arresting officer, but was convicted of the crime. On May 19, 1969, The Supreme Court concurred with Leary in Leary v. United States, declared the Marihuana Tax Act unconstitutional, and overturned his 1965 conviction.[98]

On that same day, Leary announced his candidacy for Governor of California against the Republican incumbent, Ronald Reagan. His campaign slogan was "Come together, join the party." On June 1, 1969, Leary joined John Lennon and Yoko Ono at their Montreal Bed-In, and Lennon subsequently wrote Leary a campaign song called "Come Together".[99]

On January 21, 1970, Leary received a 10-year sentence for his 1968 offense, with a further 10 added later while in custody for a prior arrest in 1965, for a total of 20 years to be served consecutively. On his arrival in prison, he was given psychological tests used to assign inmates to appropriate work details. Having designed some of these tests himself (including the "Leary Interpersonal Behavior Inventory"), Leary answered them in such a way that he seemed to be a very conforming, conventional person with a great interest in forestry and gardening.[100] As a result, he was assigned to work as a gardener in a lower-security prison from which he escaped in September 1970, saying that his non-violent escape was a humorous prank and leaving a challenging note for the authorities to find after he was gone.

For a fee of $25,000, paid by The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the Weathermen smuggled Leary out of prison in a pickup truck driven by Clayton Van Lydegraf.[101] The truck met Leary after he'd escaped over the prison wall by climbing along a telephone wire. The Weathermen then helped both Leary and Rosemary out of the US (and eventually into Algeria).[102] He sought the patronage of Eldridge Cleaver for $10,000 and the remnants of the Black Panther Party's "government in exile" in Algeria, but after a short stay with them said that Cleaver had attempted to hold him and his wife hostage.[103][104] Cleaver had put Leary and his wife under "house arrest" due to exasperation with their socialite lifestyle.[104]

In 1971, the couple fled to Switzerland, where they were sheltered and effectively imprisoned by a high-living arms dealer, Michel Hauchard, who claimed he had an "obligation as a gentleman to protect philosophers"; Hauchard intended to broker a surreptitious film deal, and forced Leary to assign his future earnings (which Leary eventually won back).[62][105] In 1972, President Richard Nixon's attorney general, John Mitchell, persuaded the Swiss government to imprison Leary, which it did for a month, but refused to extradite him to the United States.[105]

Leary and Rosemary separated later that year; she traveled widely, then moved back to the United States where she lived as a fugitive until the 1990s.[105] Shortly after his separation from Rosemary in 1972, Leary became involved with Swiss-born British socialite Joanna Harcourt-Smith, a stepdaughter of financier Árpád Plesch and ex-girlfriend of Hauchard.[105] The couple "married" in a hotel under the influence of cocaine and LSD two weeks after they were first introduced, and Harcourt-Smith would use his surname until their breakup in early 1977. They traveled to Vienna, then Beirut, and finally ended up in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1972; according to Luc Sante, "Afghanistan had no extradition treaty with the United States, but this stricture did not apply to American airliners."[62] That interpretation of the law was used by American authorities to interdict the fugitive. "Before Leary could deplane, he was arrested by an agent of the federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs."[62] Leary asserted a different story on appeal before the California Court of Appeal for the Second District, namely:[106]

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

He testified further that he had a valid passport in Kabul and that it was confiscated while he was in a line at the American Embassy in Kabul a few days prior to the day when he boarded the airplane; after his passport was confiscated, he was taken to "Central Police Headquarters"; he did not attempt to contact the American Embassy; the Kabul police held him in custody and took him to a "police hotel". The cousin of the King of Afghanistan came to see him and told him that it was a national holiday, that the King and the officials were out of Kabul, and that he (the cousin) would get a lawyer and see that Leary "had a hearing". On the morning the airplane left Kabul, officials of Afghanistan told him he was to leave Afghanistan. Leary replied he would not leave without a hearing and until he got his passport back; they said the Americans had his passport, and he was taken to the airplane.

At a stopover in the UK, as Leary was being flown back to the US in custody, he requested political asylum from Her Majesty's government to no avail. Back in America, he was held on $5 million bail ($21.5 million in 2006) since Nixon had earlier labeled him as "the most dangerous man in America."[11] At that time, it was the largest bail on a private citizen in American history.[105] The judge at his remand hearing stated, "If he is allowed to travel freely, he will speak publicly and spread his ideas,"[107] Facing a total of 95 years in prison, Leary hired criminal defense attorney Bruce Margolin. Leary mostly directed his own defense strategy, which proved to be unsuccessful, as the jury convicted him after deliberating for less than two hours.[105] The Brotherhood drug conspiracy charges were dropped for lack of evidence, but Leary received five years for his prison escape added to his original 10-year sentence.[105] In 1973, he was sent to Folsom Prison in California, and put in solitary confinement.[105][108] While in Folsom, he was placed in a cell right next to Charles Manson, and though they could not see each other, they could talk together. In their discussions, Manson was surprised and found it difficult to understand why Leary had given people LSD without trying to control them. At one point, Manson said to Leary, "They took you off the streets so that I could continue with your work."[109]

Leary feigned cooperation with the FBI's investigation of the Weathermen and its radical attorneys by giving them information that they already had or which he saw as being of little consequence; in response, the FBI gave him the code name "Charlie Thrush".[110] In a 1974 news conference, Allen Ginsberg, Ram Dass, and Leary's 25-year-old son Jack denounced Leary, calling Leary a "cop informant," a "liar," and a "paranoid schizophrenic."[111] Leary would later claim, and members of the Weathermen would later support his claim, that no one was ever prosecuted based on any information he gave to the FBI. In 1999, a letter was written by 22 'Friends of Timothy Leary' in an attempt to defend his reputation in light of the publication of FBI files relating to the same case. It was signed by authors such as Douglas Rushkoff, Ken Kesey, and Robert Anton Wilson. Susan Sarandon, Genesis P-Orridge and Leary's goddaughter Wynona Ryder also signed the letter.[104][112]

Histories written about the Weather Underground usually mention the Leary chapter in terms of the escape for which they proudly took credit. Leary sent information to the Weather Underground through a sympathetic prisoner that he was considering making a deal with the FBI and waited for their approval. The return message was, "We understand."[112][113]

While in prison, Leary was sued by the parents of Vernon Powell Cox, who had jumped from a third story window of a Berkeley apartment while under the influence of LSD. Cox had taken the drug after attending a lecture, given by Leary, favoring LSD use. Leary was unable to be present due to his incarceration, and unable to arrange for legal representation; a default judgement was entered against him in the amount of $100,000.[114]

Last two decades

Leary was released from prison on April 21, 1976 by Governor Jerry Brown. After briefly relocating to San Diego, he took up residence in Laurel Canyon and continued to write books and appear as a lecturer and (by his own terminology) "stand-up philosopher".[115] In 1978 he married filmmaker Barbara Blum, also known as Barbara Chase, sister of actress Tanya Roberts. Leary adopted Blum's son Zachary and raised him as his own. During this period, Leary took on several godchildren, including actress Winona Ryder (the daughter of his archivist, Michael Horowitz) and current MIT Media Lab director Joi Ito.[116][117]

Leary began to foster an improbable friendship with former foe G. Gordon Liddy, the Watergate burglar and conservative radio talk-show host. They toured the lecture circuit in 1982 as ex-cons debating a range of social and fiscal issues, including gay rights, abortion, welfare and the environment. Leary generally espoused left-wing views while Liddy continued to conform to a right-wing stance. The tour generated massive publicity and considerable funds for both. The personal appearances, a successful documentary called Return Engagement chronicling the tour, and the concurrent release of the autobiography Flashbacks helped to return Leary to the spotlight. In 1988, Leary held a fundraiser for Libertarian presidential candidate Ron Paul.[118][119]

While his stated ambition was to cross over to the mainstream as a Hollywood personality through proposed adaptations of Flashbacks and other projects, reluctant studios and sponsors ensured that it would never occur.[citation needed] Nonetheless, his extensive touring on the lecture circuit ensured him a very comfortable lifestyle by the mid-1980s, while his colorful past made him a desirable guest at A-list parties throughout the decade.[citation needed] He also attracted a more intellectual crowd including old confederate Robert Anton Wilson, science fiction writers William Gibson and Norman Spinrad, and rock musicians David Byrne and John Frusciante.[citation needed] In addition, he appeared in Johnny Depp's and Gibby Haynes' 1994 film Stuff, which showed Frusciante's squalid living conditions at that time.[120]

While he continued his frequent drug use privately rather than evangelizing and proselytizing the use of psychedelics as he had in the 1960s, the latter-day Leary emphasized the importance of space colonization and an ensuing extension of the human lifespan while also providing a detailed explanation of the eight-circuit model of consciousness in books such as Info-Psychology: A Re-Vision of Exo-Psychology, among several others.[105] He adopted the acronym "SMI²LE" as a succinct summary of his pre-transhumanist agenda: SM (Space Migration) + I² (intelligence increase) + LE (Life extension),[121] and credited the L5 Society co-founder Keith Henson with helping develop his interest in space migration.[citation needed]

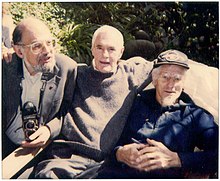

Allen Ginsberg, Timothy Leary and John C. Lilly in 1991.

Leary's colonization plan varied greatly through the years. According to his initial plan to leave the planet, 5,000 of Earth's most virile and intelligent individuals would be launched on a vessel (Starseed 1) equipped with luxurious amenities. This idea was inspired by the plotline of Paul Kantner's concept album Blows Against The Empire, which in turn was derived from Robert A. Heinlein's Lazarus Long series. Whilst in Folsom Prison in the winter of 1975-76 Leary had become enamoured by Gerard O'Neill's egalitarian plans to construct giant Eden-like High Orbital Mini-Earths (documented in the Robert Anton Wilson lecture H.O.M.E.s on LaGrange) using existing technology and raw materials from the Moon, orbital rock and obsolete satellites.[122]

In the 1980s, Leary became fascinated by computers, the Internet, and virtual reality. Leary proclaimed that "the PC is the LSD of the 1990s" and admonished bohemians to "turn on, boot up, jack in".[123][124] He became a promoter of virtual reality systems,[125] and sometimes demonstrated a prototype of the Mattel Power Glove as part of his lectures (as in From Psychedelics to Cybernetics). Around this time he befriended a number of notable people in the field such as Jaron Lanier[126] and Brenda Laurel, a pioneering researcher in virtual environments and human–computer interaction. With the rise of cyberdelic counter-culture, he served as consultant to Billy Idol in the production of the latter's 1993 album Cyberpunk.[127]

In 1990, his daughter Susan, aged 42, was arrested in Los Angeles for firing a bullet into her boyfriend's head as he slept. Twice she was ruled mentally unfit to stand trial. While in jail, after years of mental instability, she committed suicide by tying a shoelace around her neck and hanging herself.[128][129][130] After his separation and subsequent divorce from Barbara in 1992, Leary ensconced himself in a circle of artists and cultural figures encompassing figures as diverse as actors Johnny Depp, Susan Sarandon, and Dan Aykroyd; Zach Leary;[104] his grandson Ashley Martino and his granddaughters Dieadra Martino and Sara Brown; author Douglas Rushkoff; publisher Bob Guccione, Jr.; and goddaughters Ryder and artist/music–photographer Hilary Hulteen.[citation needed] Despite declining health, he maintained a regular schedule of public appearances through 1994.[131] In the same year, he was honored at a symposium of the American Psychological Association.[132]

From 1989 on, Leary had begun to re-establish his connection to unconventional religious movements with an interest in altered states of consciousness. In 1989, he appeared with friend and book collaborator Robert Anton Wilson in a dialog entitled The Inner Frontier for the Association for Consciousness Exploration, a Cleveland-based group that had been responsible for his first Cleveland, Ohio appearance in 1979. After that, he appeared at the Starwood Festival, a major Neo-Pagan event run by ACE, in 1992 and 1993[133] (although his planned 1994 WinterStar Symposium appearance was cancelled due to his declining health). In front of hundreds of Neo-Pagans in 1992 he declared, "I have always considered myself, when I learned what the word meant, I've always considered myself a Pagan."[134] He also collaborated with Eric Gullichsen on Load and Run High-tech Paganism: Digital Polytheism.[135] Shortly before his death on May 31, 1996, he recorded the Right to Fly album with Simon Stokes which was released in July 1996.[136]

Death

Etoy agents with mortal remains of Timothy Leary in 2007

In January 1995, Leary was diagnosed with inoperable prostate cancer.[137] He then notified Ram Dass and other old friends, and began the process of directed dying, which he termed "designer dying."[138] Leary did not reveal the condition to the press at that time, but did so after the death of Jerry Garcia in August.[138] Leary and Ram Dass reunited before Leary's death in May 1996, as seen in the documentary film Dying to Know: Ram Dass & Timothy Leary.[139][140]

Leary's last book before he died was Chaos and Cyber Culture, published in 1994. In it he wrote, "The time has come to talk cheerfully and joke sassily about personal responsibility for managing the dying process."[138] His book Design for Dying which tried to give a new perspective on death and dying, was published posthumously.[141] Leary wrote about his belief that death is "a merging with the entire life process."[141]

His website team, led by Chris Graves, updated his website on a daily basis as a sort of proto-blog.[138] The website noted his daily intake of various illicit and legal chemical substances with a predilection for nitrous oxide, LSD and other psychedelic drugs.[citation needed] He was noted for his strong views against the use of drugs which "dull the mind" such as heroin, morphine and (more than occasional) alcohol, and also for his trademark "Leary Biscuits" (a snack cracker with cheese and a small marijuana bud, briefly microwaved).[citation needed] At his request, his sterile house was redecorated by the staff with an array of surreal ornamentation.[citation needed] In his final months, thousands of visitors, well-wishers and old friends visited him in his California home.[citation needed] Until his last weeks, he gave many interviews discussing his new philosophy of embracing death.[141]

Movie poster for Timothy Leary's Dead.

Leary was reportedly excited for a number of years by the possibility of freezing his body in cryonic suspension, and he publicly announced in September 1988 that he had signed up with Alcor for such treatment after having appeared at Alcor's grand opening the year before.[142] He did not believe he would be resurrected in the future, but did believe that cryonics had important possibilities even though he thought it had only "one chance in a thousand".[142] He called it his "duty as a futurist", and helped publicize the process and hoped it would work for his children and grandchildren if not for him, although he said he was "lighthearted" about it.[142] He was connected with two cryonic organizations, first Alcor and then CryoCare, one of which delivered a cryonic tank to his house in the months before his death. Leary initially announced he would freeze his entire body, but due to lack of funds decided to freeze his head only.[138][104] He then changed his mind again, and requested that his body be cremated, with his ashes scattered in space.[104]

Leary died at 75 on May 31, 1996. His death was videotaped for posterity at his request, by Denis Berry and Joey Cavella, capturing his final words.[104] Berry was the trustee of Leary's archives, and Cavella had filmed Leary during his later years.[104] According to his son Zachary, during his final moments, he clenched his fist and said, "Why?", and then unclenching his fist, he said, "Why not?". He uttered the phrase repeatedly, in different intonations, and died soon after. His last word, according to Zach, was "beautiful."[143]

The film Timothy Leary's Dead (1996) contains a simulated sequence in which he allows his bodily functions to be suspended for the purposes of cryonic preservation. His head is removed, and placed on ice. The film ends with a sequence showing the creation of the artificial head used in the film.

Seven grams of Leary's ashes were arranged by his friend at Celestis to be buried in space aboard a rocket carrying the remains of 23 others, including Gene Roddenberry (creator of Star Trek), Gerard O'Neill (space physicist), and Krafft Ehricke (rocket scientist). A Pegasus rocket containing their remains was launched on April 21, 1997, and remained in orbit for six years until it burned up in the atmosphere.[144]

Leary's ashes were also given to close friends and family. In 2015, Susan Sarandon brought some of his ashes to the Burning Man festival in Black Rock City, Nevada, and put them into an art installation there. The ashes were burned, along with the installation, on September 6, 2015.[145]

Influence

Timothy Leary was an early influence on Game Theory applied to psychology having introduced the concept to the International Association of Applied Psychology in 1961, at their annual conference in Copenhagen.[146][147][148][149]

He was also an early influence on Transactional Analysis.[150][151] His concept of the four Life Scripts, dating back to 1951,[152] became an influence on TA by the late 1960s, popularised by Thomas Harris in his book, I'm OK, You're OK.[153]

Many consider Leary one of the most prominent figures during the counterculture of the 1960s, and since those times has remained influential on pop culture, literature, television,[146] film and, especially, music.

Leary coined the influential term Reality Tunnel, by which he means a kind of representative realism. The theory states that, with a subconscious set of mental filters formed from their beliefs and experiences, every individual interprets the same world differently, hence "Truth is in the eye of the beholder".[154]

His ideas influenced the work of his friend Robert Anton Wilson. This influence went both ways, and Leary admittedly took just as much from Wilson. Wilson's book Prometheus Rising was an in-depth, highly detailed and inclusive work documenting Leary's eight-circuit model of consciousness. Although the theory originated in discussions between Leary and a Hindu holy man at Millbrook, Wilson was one of the most ardent proponents of it and introduced the theory to a mainstream audience in 1977's bestselling Cosmic Trigger. In 1989, they appeared together on stage in a dialog entitled The Inner Frontier[155] hosted by the Association for Consciousness Exploration,[156] (the same group that had hosted Leary's first Cleveland appearance in 1979).[157][158]

World religion scholar Huston Smith was "turned on" by Leary after being introduced to him by Aldous Huxley in the early 1960s. The experience was interpreted as a deeply religious one by Smith, and is described in detailed religious terms in Smith's later work Cleansing of the Doors of Perception.[159] Smith asked Leary, to paraphrase, whether he knew the power and danger of what he was conducting research with. In Mother Jones Magazine, 1997, Smith commented:

First, I have to say that during the three years I was involved with that Harvard study, LSD was not only legal but respectable. Before Tim went on his unfortunate careening course, it was a legitimate research project. Though I did find evidence that, when recounted, the experiences of the Harvard group and those of mystics were impossible to tell apart — descriptively indistinguishable — that's not the last word. There is still a question about the truth of the disclosure.[160]

In popular culture

Leary, John Lennon, Yoko Ono and others recording "Give Peace A Chance".

In film

The movie Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), adapted from a 1971 novel of Hunter S. Thompson, portrays heavy psychedelic drug use and mentions Leary when the protagonist ponders the meaning of the acid wave of the sixties:

'We are all wired into a survival trip now. No more of the speed that fueled that '60s. That was the fatal flaw in Tim Leary's trip. He crashed around America selling "consciousness expansion" without ever giving a thought to the grim meat-hook realities that were lying in wait for all the people who took him seriously ... All those pathetically eager acid freaks who thought they could buy Peace and Understanding for three bucks a hit. But their loss and failure is ours too. What Leary took down with him was the central illusion of a whole life-style that he helped create ... a generation of permanent cripples, failed seekers, who never understood the essential old-mystic fallacy of the Acid Culture: the desperate assumption that somebody ... or at least some force - is tending the light at the end of the tunnel'.[161]

In the movie The Men Who Stare at Goats, Lt. Col Bill Django decides to lace the food and drinking water with LSD after claiming, "I just saw Timothy Leary".[162]

In music

The Psychedelic Experience (1964) was the inspiration for John Lennon's song "Tomorrow Never Knows", on The Beatles' album Revolver (1966).[62]

The Moody Blues recorded a track about Leary, "Legend of a Mind", on their album In Search of the Lost Chord (1968), which includes the refrain: "Timothy Leary's dead. No, no, no, no, he's outside looking in".[163]

The Who's 1970 single "The Seeker" mentions Leary in a sequence where the song's protagonist claims Leary (among other high-profile people) was unable to help them with their search for answers.[164]

- Leary recruited Lennon to write a theme song for his California gubernatorial campaign against Ronald Reagan (which was interrupted by Leary's prison sentence for cannabis possession), inspiring Lennon to come up with "Come Together" (1969), based on Leary's campaign theme and catchphrase.[163][165]

- Leary was also present when Lennon and his wife, Yoko Ono, recorded "Give Peace a Chance" (1969) during one of their bed-ins in Montreal and is mentioned in the lyrics of the song.[166]

- While in exile in Switzerland, Leary and British writer Brian Barrett collaborated with the German band Ash Ra Tempel, and recorded the album Seven Up (1973).[167] He is credited as a songwriter, and his lyrics and vocals can be heard throughout the album.[168] Commenting on the work of his friend H. R. Giger, a surrealist artist from Switzerland who won an Academy Award for his work on the film Alien, Leary noted:

Giger's work disturbs us, spooks us, because of its enormous evolutionary time span. It shows us, all too clearly, where we come from and where we are going.

— Timothy Leary, The New York Times[169]

- James Rado and Gerome Ragni reference Leary in lyrics to the closing medley of "Let The Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures)" in the hit 1967 musical Hair: "'Life is around you and in you'. Answer for Timothy Leary, deary."

- Leary had a cameo at the end of the music video for the song "Galaxie" by alternative rock group Blind Melon, in 1995.[170]

In comic books

- In 1973, El Perfecto Comics was organized by Aline Kominsky and published by The Print Mint to raise funds for the Timothy Leary Defense Fund. The comic features 31 underground artists contributing mostly one-pagers about drug experiences (primarily LSD). The front cover and a contributed one-page story are by Robert Crumb.[171]

- In 1979, Last Gasp comics published a one-shot edition of Neurocomics titled "Timothy Leary". "Evolved from transmissions of Dr. Timothy Leary as filtered through Pete Von Sholly & George DiCaprio," it is based on Leary's writings related to life, the brain, and intelligence. DiCaprio collaborated with Leary on the script.[172]

Works

Leary authored and co-authored more than twenty books and was featured on more than a dozen audio recordings. His acting career included over a dozen appearances in movies and television shows in various roles, over thirty appearances as himself. He also produced and/or collaborated with others in the creation of multimedia presentations and computer games.

In June 2011, The New York Times reported that the New York Public Library had acquired Leary's personal archives, including papers, videotapes, photographs and other archival material from the Leary estate, including correspondence and documents relating to Allen Ginsberg, Aldous Huxley, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Ken Kesey, Arthur Koestler, G. Gordon Liddy and other prominent cultural figures.[173] The collection became available in September 2013.[174]

See also

- David Peel

- Grateful Dead

- The Sekhmet Hypothesis

- Zihuatanejo Project

References

^ ab Kansra, Nikita; Shih, Cynthia W. (May 21, 2012). "Harvard LSD Research Draws National Attention". The Harvard Crimson..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Department of Psychology. "Timothy Leary (1920-1996)". Harvard University. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

^ abc Weil, Andrew T. (November 5, 1963). "The Strange Case of the Harvard Drug Scandal". Look (27).

^ Stevens, Jay (1983). Storming Heaven – LSD and the American Dream. Flamingo. pp. 273–274. ISBN 0586087966.

^ Junker, Howard (July 5, 1965). "LSD: 'The Contact High'". The Nation. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

^

Isralowitz, Richard (May 14, 2004). Drug Use: A Reference Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 183. ISBN 978-1576077085. Retrieved April 1, 2016.Leary explored the cultural and philosophical implications of psychedelic drugs

^

Donaldson, Robert H. (2015). Modern America: A Documentary History of the Nation Since 1945. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 978-0765615374. Retrieved April 1, 2016.Leary not only used and distributed the drug, he founded a sort of LSD philosophy of use that involved aspects of mind expansion and the revelation of personal truth through "dropping acid."

^ Gillespie, Nick (June 15, 2006). "Psychedelic, Man". The Washington Post.

^

Greenfield, Robert. Timothy Leary: A Biography. p. 537. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded - The Life of Timothy Leary. The Friday Project. p. 233. ISBN 1905548257.

^ abcde Mansnerus, Laura (June 1, 1996). "Timothy Leary, Pied Piper of Psychedelic 60s, Dies at 75". The New York Times. Obituary. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded - The Life of Timothy Leary. The Friday Project. p. 17. ISBN 1905548257.

^ Greenfield, Robert, Timothy Leary: A Biography (Harcourt Books, 2006), 7, 11-12, 18

^ Peter O. Whitmer, Aquarius Revisited: Seven Who Created the Sixties Counterculture That Changed America (NY: Citadel Press, 1991), 21-5

^ Greenfield, Robert, Timothy Leary: A Biography (Harcourt Books, 2006), 28–55

^ Greenfield, Robert (January 1, 2006). "Timothy Leary: A Biography". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt – via Google Books.

^ Leary, Timothy (1983). Flashbacks. Heinemann. p. 144. ISBN 0874773172.

^ Greenfield, Robert (January 1, 2006). "Timothy Leary: A Biography". Houghton Mifflin Harcourt – via Google Books.

^ "Timothy Leary". Pabook.libraries.psu.edu. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ "WSU - Myths and Legends". Washington State Magazine. 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

^ "Timothy Leary Papers 1910 - 2009". New York Public Library. 2009. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

^ Announcement of the School of Medicine - Fall and Spring Semesters, 1950 - 1951. University of California Medical Center. 1950. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ ab Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded - The Life of Timothy Leary. The Friday Project. p. 18. ISBN 1905548257. "In 1954 he became Director of Psychology Research at the Kaiser Foundation Hospital, and published nearly 50 papers in psychology journals".

^ Greenfield, Robert 2006. Timothy Leary:A Biography. Harcourt Books, 68–77.

^ Torgoff, Martin (2004). Can't Find My Way Home: America in the Great Stoned Age. Simon and Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 0-7432-3010-8.

^ Leary, Timothy; Ginsberg, Allen (1995). High Priest. Ronin Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 0-914171-80-1.

^ Current Biography - Volume 31. H. W. Wilson Company. 1970. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

^ Stevens, Jay (1987). Storming Heaven - LSD and the American Dream. Flamingo. p. 186. ISBN 0586087966.

^ Conners, Peter (2010). White Hand Society - The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg. City Lights Books. p. 22. ISBN 9780872865358.

^ Stevens, Jay (1987). Storming Heaven - LSD and the American Dream. Flamingo. p. 187. ISBN 0586087966.

^ ab New York Times, 03/12/1966, p. 25

^ Jay Stevens, "Storming Heaven", Grove Press, 1987.

^ Leary, Timothy (1957). Interpersonal diagnosis of personality: a functional theory and methodology.

^ "Timothy Leary, Pied Piper Of Psychedelic 60's, Dies at 75". New York Times. June 1, 1996. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

^ "She Comes in Colors". Playboy. HMH Publishing Company Inc. September 1, 1966. Missing or empty|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ "LIFE on LSD". Life. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010.

^ Cashman, John. "The LSD Story". Fawcett Publications, 1966

^ ab Ram Dass Fierce Grace, 2001, Zeitgeist Video

^ Sandison, Ronald (1997). Psychedelia Britannica - Hallucinogenic Drugs in Britain. Turnaround. p. 57. ISBN 1873262051. 'Psilocybin...was synthesised in Dr Hofmann's laboratory in 1958.'

^ Goffman, K. and Joy, D. 2004. Counterculture Through the Ages: From Abraham to Acid House. New York: Villard, 250–252

^ Leary, Timothy (1969). "The Effects of Consciousness Expanding Drugs in Prisoner Rehabilitation". Psychedelic Review (10).

^ Metzner, Ralph; Weil, G. (1963). "Predictive Recidivism: Base Rates for Concord Constitution". Journal for Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science.

^ Metzner, Ralph (July 1965). "A New Behavior Change Program for Adult Offenders Using Pscilocybin". Psychotherapy.

^ "Dr. Leary's Concord Prison Experiment: A 34 Year Follow-Up Study". Maps.org. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ "Reflections on the Concord Prison Project and the Follow-Up Study" (PDF). Maps.org. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Archived from the original on July 24, 2016.

^ Doblin, Rick (1998). "Dr. Leary's Concord Prison Experiment:A 34 Year Follow-Up Study". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs (30:4). pp. 419–426.

^ "International Federation For Internal Freedom – Statement of Purpose". timothylearyarchives.org. March 21, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

^ Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1992). Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD : The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. Grove Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0802130624.

^ "4: Sir Dinadan the Humorist". Lycaeum.org. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded. Friday. p. 50. ISBN 1905548257.

^ "Court Finds Lisa Bieberman Guilty Of Violations of Federal Drug Laws | News | The Harvard Crimson". Thecrimson.com. November 18, 1966. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ Hiatt, Nathaniel J. (May 23, 2016). "A Trip Down Memory Lane: LSD at Harvard". Harvard Crimson. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

^ hanna, jon (March 28, 2012). "Erowid Character Vaults: Lisa Bieberman Extended Biography". Erowid.org. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

^ Davidson, Sara (Fall 2006). "The Ultimate Trip". Tufts Magazine.

^ "The Crimson Takes Leary, Alpert to Task - News - The Harvard Crimson".

^ Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1992). Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD : The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. Grove Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0802130624.

^ abc Chevallier, Jim. “Tim Leary and Ovum - A Visit to Castalia with Ovum", Chez Jim/Ovum, March 3, 2003

^ abc Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1992). Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD : The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. Grove Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0802130624.

^ abcde Lander, Devin (January 30, 2012). "League for Spiritual Discovery". World Religions and Spiritualities Project.

^ ab Ulrich, Jennifer. “Transmissions from The Timothy Leary Papers: Evolution of the "Psychedelic" Show", New York Public Library, June 4, 2012

^ Jay Stevens Storming Heaven: LSD and the American Dream, 1998, p. 208

^ abcde Sante, Luc (June 26, 2006). "The Nutty Professor". The New York Times Book Review. 'Timothy Leary: A Biography,' by Robert Greenfield. Retrieved July 12, 2008. (Registration required (help)).

^ Wolfe, Tom (1989). The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Black Swan. p. 99. ISBN 0552993662.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded. Friday. p. 78. ISBN 1905548257.

^ Leary, Timothy (1983). Flashbacks. Heinemann. p. 206. ISBN 0434409758.

^ Leary, Timothy; Alpert, Richard; Metzner, Ralph (2008). The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Penguin Classics. p. 11. ISBN 0141189630.

^ Pennebaker, D. A. "You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You". Pennebaker Hegedus Films. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

^ "Timothy Leary's Wife Drops Out". Village Voice. February 5, 2002. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

^ McLellan, Dennis (February 9, 2002). "Rosemary W. Leary, 66; Ex-Wife of 1960s Psychedelic Guru". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

^ Sward, Susan (February 9, 2002). "Rosemary Woodruff – LSD guru's ex-wife". SF Gate. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

^ abc Hoffmann, Martina (2002). "Rosemary Woodruff Leary – Psychedelic Pioneer". MAPS Bulletin. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

^ Chevallier, Jim. “Jean McCreedy and Psychedelic Prayers", Chez Jim/Ovum, March 3, 2003

^ Marwick, Arthur. The Sixties: Cultural Revolution in Britain, France, Italy, and the United States. Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 312.

^ "Playboy Interview: Timothy Leary". Playboy. 1966. Retrieved May 8, 2016. "...the fact is that LSD is a specific cure for homosexuality."

^ Leary, Timothy (1982). Changing My Mind, Among Others: Lifetime Writings. Prentice Hall Inc. p. 256. ISBN 0131278118. 'Since homosexuality has always been a part of every society, you have to assume that there is something necessary, correct and valid - genetically natural - about it.'

^ Leary, Timothy (1982). Changing My Mind, Among Others: Lifetime Writings. Prentice Hall Inc. p. 144. ISBN 0131278118.

^ Leary, Timothy (1982). Changing My Mind, Among Others: Lifetime Writings. Prentice Hall Inc. p. 151. ISBN 0131278118.

^ "Legend of a Mind: Timothy Leary and LSD". The Pop History Dig. 2014. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

^ Leary, Timothy (1982). Changing My Mind, Among Others: Lifetime Writings. Prentice Hall Inc. p. 148. ISBN 0131278118.

^ Stevens, Jay (1987). Storming Heaven - LSD and the American Dream. Flamingo. p. 431. ISBN 0586087966.

^ "Smithsonian Folkways - The Psychedelic Experience: Readings from the Book "The Psychedelic Experience. A Manual Based on the Tibetan..." - Timothy Leary". Folkways.si.edu. March 20, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Grimesmay, William. “Chemist Who Sought to Bring LSD to the World, Dies at 75", New York Times, May 12, 2017

^ ab Forte, Robert (March 1, 1999). Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In. Park Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0892817863.

^ Graboi, Nina (May 1991). One Foot in the Future: A Woman's Spiritual Journey. Aerial Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0942344103.

^ Graboi, Nina (May 1991). One Foot in the Future: A Woman's Spiritual Journey. Aerial Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0942344103.

^ Graboi, Nina (May 1991). One Foot in the Future: A Woman's Spiritual Journey. Aerial Press. pp. 222–224. ISBN 978-0942344103.

^ Staton, Scott. “Turn On, Tune In, Drop by the Archives: Timothy Leary at the N.Y.P.L.", The New Yorker, June 11, 2011

^ Graboi, Nina (May 1991). One Foot in the Future: A Woman's Spiritual Journey. Aerial Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0942344103.

^ "Human Be-In in San Francisco 1967". The Allen Ginsburg Project. July 9, 2011. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

^ Strauss, Neil. Everyone Loves You When You're Dead: Journeys into Fame and Madness. New York: HarperCollins, 2011, 337-38

^ Krassner, Paul (2000). Paul Krassner's Impolite Interviews. Seven Stories Press. p. 304. ISBN 1888363924.

^ "LSD: Lettvin vs Leary", Open Vault from WGBH, November 30, 1967, retrieved December 21, 2011

^ Wilson, Robert Anton (1983). Prometheus Rising. Falcon Press. ISBN 0941404196. Acknowledgements - 'The eight-circuit model of consciousness in this book derives from the writings of Dr. Timothy Leary...'

^ Wilson, Robert Anton (1991). Cosmic Trigger, Volume 1. New Falcon Publications. pp. 211–213. ISBN 0941404463.

^ Harvard Crimson. “Leary Arrested On Drug Charge", Harvard Crimson, January 3, 1966

^ Graboi, Nina (May 1991). One Foot in the Future: A Woman's Spiritual Journey. Aerial Press. pp. 140–146. ISBN 978-0942344103.

^ FLASHBACKS an autobiography by Timothy Leary Chapter 28 page 236

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded. Friday. p. 99. ISBN 1905548257. 'His lawyers took the appeal against the Laredo arrest all the way to the Supreme Court, and on May 19, 1969 succeeded in getting the antiquated marijuana tax law declared unconstitutional.'

^ "The Beatles - Come Together - History and Information from the Oldies Guide at About.com". Oldies.about.com. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

^ "RE/Search Publications – Pranks! – Timothy Leary". Archived from the original on March 28, 2005. Retrieved June 28, 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Rudd, Mark (2009). Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen. New York City: William Morrow and Company. pp. 225–7. ISBN 978-0-06-147275-6.

^ Brian Flanagan (2002). The Weather Underground. The Free History Project. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

^ Leary, Timothy (1983). Flashbacks. Heinemann. pp. 304 306. ISBN 0434409758.

^ abcdefgh Coleman, Kate (February 18, 2009). "Acid Trips and Frozen Heads at San Francisco's Trippiest Party". Daily Beast.

^ abcdefghi Rein, Lisa (August 30, 2017). "Interview with Timothy Leary Archivist Michael Horowitz". Boing Boing.

^ People v. Leary, 40 Cal.App.3d 527 (1974)

^ and also reportedly declared, "He has preached the length and breadth of the land, and I am inclined to the view that he would pose a danger to the community if released." Jesse Walker (2006) "The Acid Guru's Long, Strange Trip" The American Conservative, November 6, 2006.

^ [vague]Nick Gillespie, "Psychedelic, Man," Washington Post, June 15, 2006

^ https://www.rawstory.com/2017/11/he-was-no-hippie-remembering-manson-prison-scientology-and-mind-control/

^ Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1985). Acid dreams: the complete social history of LSD: the CIA, the sixties and beyond. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3062-3.

^ Fosburgh, Lacey (September 10, 1974). "Leary Scored as 'Cop Informant' By His Son and 2 Close Friends". New York Times. New York, NY. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

^ ab "Open Letter from the Friends of Timothy Leary". Retrieved July 4, 2009.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded. Friday. p. 273. ISBN 1905548257.

^ "Notes on People". New York Times. New York, NY. January 25, 1975. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded - The Life of Timothy Leary. Friday Books. p. 256. ISBN 1905548257.

^ Leary, Timothy (1994). Chaos and Cyberculture. Ronin Publishing Inc. pp. 72 to 73. ISBN 0914171771. The Godparent: Conversation with Winona Ryder

^ "It's All Happening Poscast 36, Joi Ito Interview". It's All Happening. 2016. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2016. 'Joi was an integral part of my formative years...he was my dad's Godson....' - Zachary Leary.

^ Caldwell, Christopher (July 22, 2007) The Antiwar, Pro-Abortion, Anti-Drug-Enforcement-Administration, Anti-Medicare Candidacy of Dr. Ron Paul, New York Times

^ Gillespie, Nick (December 9, 2011) Five myths about Ron Paul, Washington Post

^ "Stuff". Invisible Movement. 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

^ Conners, Peter (2010). White Hand Society - The Psychedelic Partnership of Timothy Leary and Allen Ginsberg. City Lights Books. p. 258. ISBN 9780872865358.

^ Leary, Timothy (1982). Changing My Mind Among Others. Prentice Hall Inc. p. 231. ISBN 0131278118. 'O'Neill's proposal for mini-Earths was obviously the next step in human evolution...'

^ Leary, Timothy; Horowitz, Michael; Marshall, Vicky (1994). Chaos and Cyber Culture. Ronin Publishing. ISBN 0-914171-77-1.

^ Ruthofer, Arno (1997). "Think for Yourself; Question Authority". Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved February 2, 2007.

^ Elmer-Dewitt/Dallas, Philip (September 3, 1990). "Technology: (Mis)Adventures In Cyberspace". Time Magazine. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

^ Forte, Robert (1999). Timothy Leary - Outside Looking In. Park Street Press. p. 129141. ISBN 0892817860.

^ Saunders, Michael (May 19, 1993). "Billy Idol turns 'Cyberpunk' on new CD". The Boston Globe. 135 Morrissey Boulevard. Boston, Massachusetts, United States: P. Steven Ainsley. Archived from the original on May 30, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

^ Gilmore, Mikal (July 11–25, 1996). "Timothy Leary 1920-1996". Rolling Stone.

^ Mansnerus, Laura (June 1, 1996). "Timothy Leary, Pied Piper Of Psychedelic 60's, Dies at 75". The New York Times.

^ "Timothy Leary Daughter Hangs Self in Cell, Dies in Hospital". Los Angeles Times. September 6, 1990.

^ Higgs, John (2006). I Have America Surrounded - The Life of Timothy Leary. Friday Books. p. 268. ISBN 1905548257. 'The last 17 months of Tim's life were a flurry of activity. There were records to be made, documentaries to film...and countless personal appearances. The stream of press that flocked to his door for interviews seemed never ending.'

^ Forte, Robert (1999). Timothy Leary – Outside Looking In. Park Street Press. p. 8. ISBN 0892817860.