Economic interventionism

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

By application |

Notable economists |

Lists |

Glossary |

|

Red tape binds 19th century documents, the origin of phrase "red tape" to criticize economic interventionist laws and regulations

Economic interventionism (sometimes called state interventionism) is an economic policy perspective favoring government intervention in the market process to correct the market failures and promote the general welfare of the people. An economic intervention is an action taken by a government or international institution in a market economy in an effort to impact the economy beyond the basic regulation of fraud and enforcement of contracts and provision of public goods.[1][2] Economic intervention can be aimed at a variety of political or economic objectives, such as promoting economic growth, increasing employment, raising wages, raising or reducing prices, promoting income equality, managing the money supply and interest rates, increasing profits, or addressing market failures.

The term intervention assumes on a philosophical level that the state and economy should be inherently separated from each other;[3] therefore the terminology applies to capitalist market-based economies where government action interrupts the market forces at play through regulations, economic policies or subsidies (state-owned enterprises that operate in the market do not constitute an intervention). The term intervention is typically used by advocates of laissez-faire and free markets.[4][5]Capitalist market economies that feature high degrees of state intervention are often referred to as mixed economies.[6]

Contents

1 Political perspectives

2 Effects

3 United States government interventions

4 See also

5 References

Political perspectives

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

History

|

Ideas

|

People

|

By region

|

|

Liberals and other advocates of free market or laissez-faire economics generally view government interventions as harmful due to the law of unintended consequences, belief in government's inability to effectively manage economic concerns and other considerations. However, modern liberals (in the United States) and contemporary social democrats (in Europe) are inclined to support interventionism, seeing state economic interventions as an important means of promoting greater income equality and social welfare. Furthermore, many center-right groups such as Gaullists, paternalistic conservatives and Christian democrats also support state economic interventionism to promote social order and stability. National-conservatives also frequently support economic interventionism as a means of protecting the power and wealth of a country or its people, particularly via advantages granted to industries seen as nationally vital.[citation needed] Such government interventions are usually undertaken when potential benefits outweigh the external costs.

On the other hand, Marxists often feel that government welfare programs might interfere with the goal of overthrowing capitalism and replacing it with socialism because a welfare state makes capitalism more tolerable to the average worker.[7] Socialist]]s often criticize interventionism (as supported by social democrats and social liberals) as being untenable and liable to cause more economic distortion in the long-run. From this perspective, any attempt to patch up [[capitalism's contradictions would lead to distortions in the economy elsewhere, so that the only real and lasting solution is to entirely replace capitalism with a socialist economy.[8]

Effects

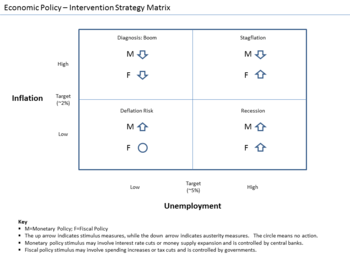

Typical intervention strategies under different conditions

The effects of government economic interventionism are widely disputed.

Regulatory authorities do not consistently close markets, yet as seen in economic liberalization efforts by states and various institutions (International Monetary Fund and World Bank) in Latin America, "financial liberalization and privatization coincided with democratization".[9] One study suggests that after the lost decade an increasing "diffusion of regulatory authorities" emerged[10] and these actors engaged in restructuring the economies within Latin America. Latin America through the 1980s had undergone a debt crisis and hyperinflation (during 1989 and 1990). These international stakeholders restricted the state's economic leverage and bound it in contract to co-operate.[11] After multiple projects and years of failed attempts for the Argentine state to comply, the renewal and intervention seemed stalled. Two key intervention factors that instigated economic progress in Argentina were substantially increasing privatization and the establishment of a currency board.[11] As one can see this exemplifies global institutions including, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, instigate and propagate openness to increase foreign investments and economic development within places, including Latin America.[2]

In Western countries, government officials theoretically weigh the cost benefit for an intervention for the population or they succumb beneath coercion by a third private party and must take action.[12] Intervention for economic development is also at the discretion and self-interest of the stake holders, the multifarious interpretations of progress and development theory.[13] To illustrate this, during the 2008 financial crisis the government and international institutions did not prop Lehman Brothers up, therefore allowing them to file bankruptcy. Days later when the American International Group waned towards collapsing, the state spent public money to keep it from falling.[12] These corporations have interconnected interests with the state, therefore their incentive is to influence the government to designate regulatory policies[12] that will not inhibit their accumulation of assets.[7] In Japan, Abenomics is a form of intervention with respect to Prime Minister Shinzō Abe's desire to restore the country's former glory in the midst of a globalized economy.[14]

United States government interventions

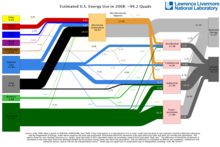

American energy sources and sinks

President Richard Nixon signed amendments to the Clean Air Act in 1970 that expanded it to mandate state and federal regulation of both automobiles and industry.[15] It was later further amended in 1977 and 1990.

- One of the first modern environmental protection laws enacted in the United States was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), which requires the government to consider the impact of its actions or policies on the environment. NEPA remains one of the most commonly used environmental laws in the nation. In addition to NEPA, there are numerous pollution-control statutes that apply to such specific environmental media as air and water. The best known of these laws are the Clean Air Act (CAA), Clean Water Act (CWA), and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) commonly referred to as Superfund. Among the many other important pollution control laws are the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), Oil Pollution Prevention Act (OPP), Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), and the Pollution Prevention Act (PPA).[16]

United States pollution control statutes tend to be numerous and diverse and many of the environmental statutes passed by Congress are aimed at pollution prevention. However, they often need to be expanded and updated before their impact is fully realized. Pollution-control laws are generally too broad to be managed by existing legal bodies, so Congress must find or create an agency for each that will be able to implement the mandated mission effectively.[16]

During World War I, the United States government intervention mandated that the manufacturing of cars be replaced with machinery to successfully fight the war. Today, government intervention could be used to break the United States dependence on oil by mandating American automakers to produce electric cars such as the Chevrolet Volt. Recently, Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm said: "We need help from Congress", namely renewing the clean energy manufacturing tax credit and the tax incentives that make plug-ins cheaper to buy for consumers.[17] It is possible that government mandated carbon taxes could be used to improve technology and make cars like the Volt more affordable to consumers. However, current bills suggest carbon prices would only add a few cents to the price of gasoline, which has negligible effects compared to what is needed to change fuel consumption.[17] Washington is beginning to invest in car manufacturing industry by partially providing $6 billion in battery-related public and private investments since 2008 and the White House has taken credit for putting a down payment on the American battery industry that may reduce battery prices in the coming years.[17] Currently, opponents believe that the carbon dioxide emissions tax the United States government introduced on new cars is unfair on consumers and looks like a revenue-raising fiscal intervention instead of limiting harm caused to the environment.[18] A national fuel tax means everyone will pay the tax and the amount of tax each individual or company pays will be proportional to the emissions they generate. The more they drive, the more that they would need to pay.[18] While this tax is supported by the motor manufacturers, stipulations confirmed by the National Treasury state that minibuses and midibuses will receive a special exclusion from the emissions tax on cars and light commercial vehicles which went into effect on 1 September 2010. This exclusion is because these taxi vehicles are used for public transport, which opponents of the tax disagree with.[18]

During George W. Bush’s 2000 campaign, he promised to commit $2 billion over ten years to advance clean coal technology through research and development initiatives. According to Bush supporters, he fulfilled that promise in his fiscal year 2008 budget request, allocating $426 million for the Clean Coal Technology Program.[19] During his administration, Congress passed the Energy Policy Act of 2005, funding research into carbon-capture technology to remove and bury the carbon in coal after it is burned. The coal industry received $9 billion in subsidies under the act as part of an initiative supposedly to reduce American dependence on foreign oil and reduce carbon emissions. This included $6.2 billion for new power plants, $1.1 billion in tax breaks to install pollution-control technology and another $1.1 billion to make coal a cost efficient fuel. The act also allowed redefinitions of coal processing, such as spraying on diesel or starch, to qualify them as "non-traditional", allowing coal producers to avoid paying $1.3 billion in taxes per year.[19]

The Waxman-Markey bill, also called the American Clean Energy and Security Act, passed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee in 2010, targets dramatic CO2 reductions after 2020, when the price of the permits would rise to further limit consumers' demand for CO2-intensive goods and services. The legislation is targeting 83 percent reduction in CO2 emissions from 2005 levels in the year 2050.[20] A study by the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the price of the permit would rise from about $20 a ton in 2020 to more than $75 a ton in 2050.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) shows that federal subsidies for coal in the United States were planned to be reduced significantly between 2011 and 2020, provided the budget passed through Congress and reduces four coal tax preferences, namely Expensing of Exploration and Development Costs, Percent Depletion for Hard Mineral Fossil Fuels, Royalty Taxation and Domestic Manufacturing Deduction for Hard Mineral Fossil Fuels.[21] The fiscal 2011 budget proposed by the Obama administration would cut approximately $2.3 billion in coal subsidies during the next decade.[22]

See also

- American School (economics)

- Austrian School

- Crowding out

- Dirigisme

- Fiscal policy

- Indicative planning

- Keynesian economics

- Mixed economy

- Monetary policy

- Rent-seeking

References

^ Karagiannis, Nikolaos (2001). "Key Economic and Politico-Institutional Elements of Modern Interventionism". Social and Economic Studies. 50 (3/4): 17–47. JSTOR 27865245..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab von Mises, Ludwig (1998). Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (PDF). New York: The Foundation for Economic Education. pp. 10–12.

^ Lu, Catherine. "Intervention". Encyclopedia of Political Theory. SAGE. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

^ von Mises, Ludwig (1998). Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (PDF). New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc. pp. 10–12.

^ Brown, Douglas (11 November 2011). Towards a Radical Democracy (Routledge Revivals): The Political Economy of the Budapest School. Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0415608794.

^ Brown, Douglas (11 November 2011). Towards a Radical Democracy (Routledge Revivals): The Political Economy of the Budapest School. Routledge. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0415608794.The political definition refers to the degree of state intervention in what is basically a capitalist market economy. Thus this definition 'portray[s] the phenomenon in terms of state encroaching upon market and thereby suggest[s] that market is the natural or preferable mechanism.

^ ab Pierson, Chris (1999). Gamble; et al., eds. Marxism and Social Science. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 176–77. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.397.5282.

^ Schweickart, David (2006). "Democratic Socialism". Encyclopedia of Activism and Social Justice. "Social democrats supported and tried to strengthen the basic institutions of the welfare state – pensions for all, public health care, public education, unemployment insurance. They supported and tried to strengthen the labor movement. The latter, as socialists, argued that capitalism could never be sufficiently humanized, and that trying to suppress the economic contradictions in one area would only see them emerge in a different guise elsewhere. (E.g., if you push unemployment too low, you'll get inflation; if job security is too strong, labor discipline breaks down; etc.)"

^ Karagiannis, Nikolaos (2001). "Key Economic and Politico-Institutional Elements of Modern Interventionism". Social and Economic Studies. 50 (3/4): 19–21. JSTOR 27865245.

^ Jordana, Jacint; David Levi-Faur (Mar 2005). "The Diffusion of Regulatory Capitalism in Latin America: Sectoral and National Channels in the Making of a New Order". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 598 (The Rise of Regulatory Capitalism: The Global Diffusion of a new Order): 102–24. doi:10.1177/0002716204272587. JSTOR 25046082.

^ ab de Beaufort Wijnholds, J. Onno. "The Argentine Drama: A View from the IMF Board" (PDF). The Crisis That Was Not Prevented: Argentina, the IMF, and Globalisation. FONDAD. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

^ abc Lanchester, John (November 5, 2009). "Bankocracy". London Review of Books. 31 (21).

^ von Mises, Ludwig (1998). Interventionism: An Economic Analysis (PDF). New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, Inc. pp. 1–51.

^ del Rosario, King (15 August 2013). "Abenomics and the Generic Threat". Retrieved 15 August 2013.

^ "40th Anniversary of the Clean Air Act". Environmental Protection Agency. 22 January 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

^ ab "Laws and Regulations, United States". Pollution Issues. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

^ abc "Electric Carmakers Focus on Incentives, Not Carbon Prices". Carbon Offsets Daily. 3 August 2010. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

^ abc "State puts cart before horse on vehicle carbon tax". Carbon Offsets Daily. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

^ ab "U.S. Coal Facts". The Indypendent. 7 June 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

^ "WRI Summary of H.R. 2454, the American Clean Energy and Security Act (Waxman-Markey)". World Resources Institute. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

^ "US 2011 budget may cut coal subsidies". Bury Coal. 3 March 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

^ (February 2, 2010). "Obama budget would cut coal subsidies". McClatchy. 2 February 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.