Philadelphia Tribune

| Type | African-American daily |

|---|---|

| Owner(s) | privately held |

| Founder(s) | Christopher James Perry, Sr. |

| Founded | 1884 |

| Language | English |

| Headquarters | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| ISSN | 0746-956X |

| Website | www.phillytrib.com |

Modern image of the Philadelphia Tribune building at 520 South 16th Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Philadelphia Tribune is the oldest continuously published African-American newspaper in the United States.[1]

The paper began in 1884 when Christopher J. Perry published its first copy. Throughout its history, The Philadelphia Tribune has been committed to the social, political, and economic advancement of African Americans in the Greater Philadelphia region. During a time when African Americans struggled for equality, the Tribune acted as the "Voice of the black community" for Philadelphia. Historian V. P. Franklin asserted that the Tribune "was (and is) an important Afro-American cultural institution that embodied the predominant cultural values of upper-, middle-, and lower-class Black Philadelphians."[2]:276

In the early 21st century, the paper is headquartered at 520 South 16th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It publishes on Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Sunday. The Philadelphia Tribune also publishes the Tribune Magazine, Entertainment Now, Sojourner, The Learning Key, and The Sunday Tribune. The Tribune has a weekly readership of about 625,000, and is mostly read by people living in the Philadelphia-Camden Metro Area, as well as in Chester.[3] The Tribune has received the John B. Russwurm award as "Best Newspaper" in the country seven times since 1995.[3]

Contents

1 Christopher James Perry

2 History

2.1 Beginnings

2.2 Post-Reconstruction migration

2.3 Great Migration

2.4 The Great Depression and New Deal

2.5 Civil Rights

3 See also

4 Further reading

5 References

6 External links

Christopher James Perry

Christopher J. Perry was born on September 11, 1854[4] in Baltimore, Maryland to free people of color. Perry attended school in Baltimore, gaining a positive reputation in his local community through his public speeches.[3] After he graduated from high school in 1873, the ambitious Perry migrated to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, feeling there were more opportunities in the northern city, given the waning days of Reconstruction in the South.[2]:261

Once in Philadelphia, Perry began writing for local newspapers such as the Northern Daily and the Sunday Mercury. He wrote a column titled, "Flashes and Sparks" for the Mercury, which provided information to the growing Black community in Philadelphia. Other migrants from the South were also settling there.[2] Through his regular columns, Perry gained positive attention from the educated members of the African-American community in Philadelphia.[5] However, in 1884, the Sunday Mercury went bankrupt and Perry was without a job.[2]:262

Later that year on November 27, 1884, Perry began his own newspaper entitled the Philadelphia Tribune. He ran the operation as the owner, reporter, editor, copier, and advertiser.[6] Perry worked on the Tribune until his death in 1921. Throughout his career with the Tribune, Perry promoted the advancement of African Americans in society and covered issues affecting their daily lives.[6]

History

Beginnings

An image from Garland Penn's book The Afro-American Press and Its Editors

When the Tribune began publication in 1884, it was a weekly, one-page paper, publishing from 725 Sansom Street. Despite the challenges Black businesses faced during the late nineteenth century, especially in journalism, the Tribune enjoyed unusual success during its early years, and it averaged 3,225 copies weekly by 1887. In 1891, Perry and the Tribune received national recognition when Garland Penn, a prominent advocate for African-American journalism, praised the Philadelphia newspaper in his book The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. In his book, Penn complimented the Tribune's consistency and reliability.[2]:262 However, the Tribune was not the only African-American newspaper circulating in Philadelphia at the time. The Tribune competed against other African-American newspapers during its first few decades, such as The Philadelphia Standard Echo, The Philadelphia Sentinel, The Philadelphia Defender, and The Courant. But by 1900, the Tribune became the leading voice of Black Philadelphia, and W.E.B. Du Bois referred to it as "the chief news-sheet" in the city.[2]:263

Post-Reconstruction migration

After Reconstruction ended in 1877, many African Americans from the South migrated to northern cities in search of a better life. The city went through a fundamental transformation as African Americans flooded the city looking for jobs.[4] Racial tensions divided Philadelphia as the new Black migrants crowded neighborhoods and competed with Whites for jobs, including Irish immigrants and, increasingly, other European immigrants. During the migration, Perry and The Tribune served as an outlet to educate and inform Black Philadelphians, and it helped the new migrants adjust to their new city. It covered job openings, civic affairs, social events, and church news.[4] Rather than just report the news, the Tribune committed itself to helping to improve the standard of living for African Americans in Philadelphia. The Tribune openly supported and advertised civic groups such as The Armstrong Association, Negro Migration Committee, and the National Urban League of Philadelphia in order to combat the increasing discrimination found within the city.[2]:266

Great Migration

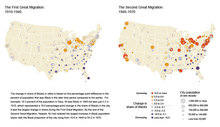

Great Migration Urban Populations

Beginning about 1910, a new wave of black migrants moved to Philadelphia, as part of the Great Migration from the rural South to northern and midwestern industrial cities. The expansion of railroads drew many new workers. After World War I began, industries began to recruit blacks as whites were drafted into the military. The city was crowded and new migrants moved into White neighborhoods, resulting in violent reactions in working-class areas. White mobs formed to intimidate Black families. In 1914, a White mob attacked and destroyed the new home of a Black woman, but the Philadelphia Department of Public Safety failed to investigate the crime and no White newspapers reported the incident. The managing editor of the Tribune, G. Grant Williams, reported the case and encouraged African-Americans to join the police force and become part of shaping the city.[2]:268

The newspaper worked with the Colored Protective Association to help defend African-Americans who were unfairly arrested. Williams also wrote articles on how to protect community women from racial violence, as well as giving advice on morals and values. As a way to create a cultural identity and unity among Blacks in the city, the Tribune publicized free lectures and invited respected Church leaders to write columns for the paper.[2]:264–265

As White men left the city for war assignments in Europe, industrial jobs opened up for African-Americans and the Tribune covered the job market. However, after the war ended in 1918, White veterans returned and competed fiercely with African Americans for jobs in the post-war recession. Racial riots broke out in the summer of 1919 in many industrial cities. Since White men appeared more qualified for work, the Tribune spent the 1920s encouraging African-Americans to receive an education or learn a trade at an industrial school.[2]

By 1920, the Tribune was distributing 20,000 newspapers weekly and had earned a reputation as one of the top African-American newspapers in the country.[4] In 1921, its founder and chief editor Christopher Perry died; he was succeeded by G. Grant Williams. Williams died in June 1922. Eugene Washington Rhodes became the managing editor, serving for more than two decades until 1944. Under Rhodes, the Tribune went through aesthetic enhancements as the print size and column size grew larger. Despite an increase in cost, the Tribune remained a hot seller.[2]:269

The Great Depression and New Deal

In April 1929, months before the Stock Market Crash, Philadelphia's Black unemployment rate was 45 percent higher than White unemployment.[7]:193 During the Great Depression, African-Americans in Philadelphia and throughout the country suffered higher levels of unemployment due to their lack of skills and qualifications.[8] Rhodes and the Tribune wrote articles to help African-Americans improve their standard of living during the difficult times. The newspaper provided information on relief help by advertising Black social organizations, churches, and schools. Also, by 1930, Tribune and the N.A.A.C.P. of Philadelphia would report unfair employment practices by local businesses, and the negative publicity would pressure the businesses into reassessing their hiring process.[2]:273–274

When Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced his New Deal program in 1933, the Tribune covered the new federal relief agencies and exposed the discrimination some of the programs practiced against African-Americans.[2]:274 Although Roosevelt and the New Deal aimed to assist struggling Americans, the Tribune faced a political dilemma. Historically, the Tribune had supported the Republican Party because of its ties to Abraham Lincoln and the Abolitionists. In order to keep Republicans in control of local and State politics, Rhodes and the Tribune remained loyal to the party of Lincoln and criticized Roosevelt and his Democratic Party. The confusing message the Tribune offered allowed other African-American newspapers in Philadelphia to gain readers. In 1935, the Philadelphia Independent openly supported Roosevelt and the Democrats, and surpassed the Tribune as the most popular African-American newspaper in Philadelphia with 30,000 weekly subscribers. In the mid-1930s, Rhodes introduced new elements to the paper as a way to gain more readers. He added an editorial that showcased African-American achievements and also a comic strip to the weekly paper. However, some argue Rhodes used these new elements to promote middle-class values that reflected the principles of the Republican Party.[7]:196–198

Civil Rights

During the 1920s, after John Asbury and Andrew Stevens became the first African-Americans elected to the Pennsylvania State legislature, the Tribune increased its political activity in the city. In 1921, when the State legislature introduced an Equal Rights Bill, the Tribune reported which representatives opposed it.[2]:270–271 The paper remained a strong advocate for the bill until 1935, when Pennsylvania passed a state Equal Rights Bill.

Also during the 1920s and 1930s, the Tribune played a monumental role in officially ending segregation in Philadelphia schools. Upset over the Philadelphia School Board's lack of action to end segregation, The Tribune organized the Defense Fund Committee in 1926. It collected funds to support a court challenge to the school board. By 1932, the Tribune succeeded in gaining appointment of African-Americans to the School Board, which eventually ended segregation in Philadelphia's public schools.[2]:272-273

Thanks to the Tribune’s coverage of and coalition with the NAACP, Philadelphia captured national attention in 1965 when demonstrators protested to end segregation at Girard College. It had been established as a high school to educate poor boys in the city but historically had admitted only whites. Martin Luther King Jr. visited Philadelphia, strengthening the city and the Tribune’s connection to the national Civil Rights Movement.[9]

See also

- List of newspapers in Pennsylvania

Further reading

- Banner-Haley, Charles Pete. "The Philadelphia Tribune and the Persistence of Black Republicanism during the Great Depression." In Pennsylvania History, Vol. 65 no. 2 (Spring 1998), 190-202.

- Franklin, V.P. "Voice of the Black Community: The Philadelphia Tribune, 1912-1940." In Pennsylvania History Vol. 51 no. 4 (October, 1984), 261-284.

- Taylor, Frederick. "Black Musicians in 'The Philadelphia Tribune,' 1912-20." In The Black Perspective in Music Vol. 18 no. 1/2 (1990), 127-140.

References

^ "The Philadelphia Tribune, Founded". The African American Registry. 2013. Archived from the original on 2010-11-24. Retrieved 2017-12-07.Sat, 1884-11-22. On this date in 1884, Christopher Perry founded the Black Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest continually published non-church newspaper, and the first black newspaper. ...Reference: The Encyclopedia Britannica, Fifteenth Edition. (1996).

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em} Page footer says "© Copyright, African American Registry, 2000 to 2013".

^ abcdefghijklmno Franklin, V. P. (October 1984). "'The Voice of the Black Community': The Philadelphia Tribune, 1912-1941". Pennsylvania History, Vol. 51, no. 4.

^ abc "About Us". The Philadelphia Tribune. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

^ abcd Costello, Lisa. "The Philadelphia Tribune". PhilaPlace. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

^ "Perry, Christopher J. (1854-1920) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed". www.blackpast.org. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

^ ab Taylor, Frederick (1990). "Black Musicians in "The Philadelphia Tribune", 1912-1920". The Black Perspective in Music Vol. 18 no. 1/2: 128.

^ ab Banner-Haley, Charles Pete (Spring 1998). "The Philadelphia Tribune and the Persistence of Black Republicanism during the Great Depression". Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. 65 no. 2.

^ "Great Depression | Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia". philadelphiaencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

^ "Stories from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia". Goin' North. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

External links

- The Philadelphia Tribune

- Online Edition of the Philadelphia Tribune

- PhilaPlace from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

- http://www.blackpast.org/aah/perry-christopher-j-1854-1920

- West Chester University, Goin' North: Stories from the First Great Migration to Philadelphia, 2014.