Garegin Nzhdeh

Garegin Nzhdeh | |

|---|---|

| |

| Birth name | Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan |

| Born | (1886-01-01)January 1, 1886 Güznüt, Erivan Governorate, Russian Empire (now in Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, Azerbaijan) |

| Died | 21 December 1955(1955-12-21) (aged 69) Vladimir, Soviet Union |

| Buried | Spitakavor Monastery |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1907–1921 |

| Rank | Sparapet |

| Battles/wars | First Balkan War Second Balkan War Armenian national liberation movement World War I

Armenian–Azerbaijani War |

| Awards | see below |

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan (Armenian: Գարեգին Տէր-Յարութիւնեան) better known by his nom de guerre Garegin Nzhdeh (Armenian: Գարեգին Նժդեհ) (1 January 1886 – 21 December 1955) was an Armenian statesman and military strategist. As a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, he was involved in national liberation struggle and revolutionary activities during the First Balkan War and World War I. Garegin Nzhdeh was one of the key political and military leaders of the First Republic of Armenia (1918–1921), and is widely admired as a charismatic national hero by Armenians.[1][2]

In 1921, he instrumented the establishment of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, an anti-Bolshevik state that became a key factor that led to the inclusion of the province of Syunik into Soviet Armenia.[3][4] During World War II, he assisted the Armenian Legion of the Wehrmacht, the armed forces of Nazi Germany, he hoped that if Germany succeeded in conquering the USSR, they would be able to grant Armenia independence.[5][6]

Contents

1 Early years and education

2 Balkan wars

3 World War I

4 Battle of Karakilisa

5 Republic of Mountainous Armenia

6 Organizational activities

7 Arrest and trial

8 Life in prison and death

9 Legacy

10 Awards

11 Works

12 Books

13 Portrayal

14 References

15 External links

Early years and education

Garegin Ter-Harutyunyan was born on 1 January 1886 in the village of Kznut, Nakhchivan. He was the youngest of four children born to a local village priest. He lost his father, Priest Yeghishe, in his childhood. Nzhdeh got his early education at a Russian school in Nakhichevan City. He continued his higher education in Tiflis Gymnasium (Russian: Тифлисская гимназия, Tiflisskaya Gimnaziya). At the age of 17 he joined the Armenian national liberation movement. The word nzhdeh in Armenian means "pilgrim" or "emigrant".[7] Shortly after, he moved to St. Petersburg to continue his education in a local university. After two years of studying at the Faculty of Law, he left St. Petersburg University and returned to the Caucasus in order to participate in the Armenian national movements against the Ottoman Empire.

In 1906, Nzhdeh moved to Bulgaria, where he completed his education at the Dmitry Nikolov Military College of Sofia and got a rank of Lieutenant in 1907.

Balkan wars

Nzhdeh as a Bulgarian Army Officer during the Balkan Wars

Garegin Nzhdeh during the Balkan Wars, 1912–1913.

In the same year he returned to Armenia. In 1908 he joined the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and participated in the Iranian revolution along with Yeprem Khan and Murad of Sebastia.[citation needed]

In 1909, upon his return to the Caucasus, Nzhdeh was arrested by the Russian authorities and spent 3 years in prison.

In 1912, together with General Andranik Ozanian, he formed an Armenian battalion within Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps of the Bulgarian Army to fight against the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan wars, for the liberation of Thrace and Macedonia. During the Second Balkan War he was wounded. For the brave and extraordinary performance of the Armenian fighters, Bulgarian military authorities honoured Nzhdeh with the Cross of Bravery.[8]

World War I

Prior to World War I, after an amnesty granted by the Russian authorities in 1914, Nzhdeh returned to the Caucasus to prepare the formation of the Armenian volunteer units within the Russian army to fight against the Ottoman Empire. During the first stage of the war, in 1915, he was appointed as an assistant-commander to Drastamat Kanayan of the 2nd Armenian unit. Later on, in 1916, he commanded the special Armenian-Yezidi military unit. After the Russian Revolution and the withdrawal of the Russian army, Nzhdeh fought in the skirmishes of Alajay (near Ani, spring 1918), allowing a secure passage for the retreated Armenian volunteer forces into Alexandrapol.

Battle of Karakilisa

General Garegin Nzhdeh and Colonel Ruben Narinian in autumn 1920

After clashing with Turkish forces in Alexandropol, today known as Gyumri, the Armenian fighters led by Nzhdeh dug-in and built fortifications in Karakilisa.

Nzhdeh played a key role in organizing the troops for the defense of Karakilisa in May 1918. He managed to mobilize a population of despairing and hopeless locals and refugees for the coming fight through his inspiring speech in the Dilijan church yard, where he called the Armenians to a sacred battle: "Straight to the frontline, our salvation is there." Nzhdeh was wounded in the ensuing clash and, after a violent battle of 4 days, both sides had serious casualties. The Armenians ran out of ammunition and had to withdraw. Although the Ottoman army managed to invade Karakilisa itself, they had no more resources to continue deeper into Armenian territory.[9]

After the declaration of the independent First Republic of Armenia, Nzhdeh was appointed governor of Nakhijevan, and later on, in August 1919, commander of the southern corps of the Armenian army.[10]

Republic of Mountainous Armenia

Republic of Mountainous Armenia emblem

Nzhdeh in Goris, Republic of Mountainous Armenia (1921)

The Soviet 11th Red Army's invasion of the First Republic of Armenia started on 29 November 1920. Following the sovietization of Armenian on 2 December 1920, the Soviets pledged to take steps to rebuild the army, to protect the Armenians and not to persecute non-communists, although the final condition of this pledge was reneged when the Dashnaks were forced out of the country.

The Soviet Government proposed that the regions of Nagorno-Karabagh and Zangezur should be part to the Soviet Azerbaijan. This step was strongly rejected by Nzhdeh. A convinced anti-Bolshevik, he led the defense of Syunik against the rising Bolshevik movement and declared Syunik as a self-governing region in December 1920. In January 1921 Drastamat Kanayan sent a telegram to Nzhdeh, suggesting allowing the sovietization of Syunik, through which they could gain the support of the Bolshevik government in solving the problems of the Armenian lands. As a response, Nzhdeh did not depart from Syunik and continued his struggle against the Red Army and Soviet Azerbaijan, struggling to maintain the independence of the region.[11][12]

On 18 February 1921, the Dashnaks led an anti-Soviet rebellion in Yerevan and seized power. The ARF controlled Yerevan and the surrounding regions for almost 42 days before being defeated by the numerically superior Red Army troops later in April 1921. The leaders of the rebellion then retreated into the Syunik region.

The 2nd Pan-Zangezurian congress, held in Tatev, announced on 26 April 1921 the independence of the self-governing regions of Daralakyaz (Vayots Dzor), Zangezur, and Mountainous Artsakh, under the name of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia (Lernahaystani Hanrapetutyun).

Following the declaration of independence of the Republic of the Mountainous Armenia from Soviet Armenia, he was proclaimed Prime Minister and Minister of Defense.

Between April and July 1921, the Red Army conducted massive military operations in the region, attacking Syunik from north and the east. After months of fierce battles with the Red Army, the Republic of Mountainous Armenia capitulated in July 1921 following Soviet Russia's promises to keep the mountainous region as a part of Soviet Armenia. After the conflict, Nzhdeh, his soldiers, and many prominent Armenian intellectuals, including leaders of the first independent Republic of Armenia, crossed the border into the neighboring Persian city of Tabriz.

Organizational activities

Nzhdeh in 1930s

Garegin Nzhdeh at the founding of the Armenian Youth Federation (Tseghakron) in Boston in 1933

After leaving Syunik, Nzhdeh spent four months in the Persian city of Tabriz. Soon after, he moved to Sofia, Bulgaria where he started a family by marrying Epime, a local Armenian girl and establishing in Bulgaria.

Nzhdeh was involved in organizational activities in Bulgaria, Romania and the United States through his frequent visits to Plovdiv, Bucharest and Boston.

In 1933, by the decision of ARF Dashnaktsutyun, Nzhdeh moved to USA along with his partisan, Kopernik Tanterjian. This movement led to the foundation of the Armenian Youth Federation, the youth organization of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation, in Boston, Massachusetts.

He visited several states and provinces in United States and Canada, inspiring the Armenian communities that had established themselves there, and founding an Armenian Youth movement called Tseghakron (Armenian: Ցեղակրոն) (see Tseghakronism), which later renamed itself the "Armenian Youth Federation".

In 1937, he was back in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, where he began to publish the Razmig Armenian newspaper. At the end of the 1930s, along with a group of Armenian intellectuals in Sofia, he founded the Taron Nationalist Movement and published its organ Taroni Artsiv paper.

During his life in Bulgaria, Nzhdeh maintained close contacts with revolutionary organizations of Macedonian Bulgarians and Bulgarian Symbolist poet Theodore Trayanov.[13]

Arrest and trial

House of Nzhdeh in Sofia

During World War II, Nzhdeh suggested supporting the Axis powers if the latter would make a decision to attack Turkey. Operation Gertrud, a joint German-Bulgarian project about attacking Turkey in the event that Ankara joined the allies, was largely discussed in Berlin.[14] The Armenian military unit, which was supposed to be used against Turkey was sent to the Eastern front, to the Crimean peninsula, in 1943. Nzhdeh requested the detachment's return, and terminated his connections with Nazi Germany. On 9 September 1944 Nzhdeh wrote a letter to Stalin offering his support were the Soviet leadership to attack Turkey.[15] A Soviet plan to invade Turkey in order to punish Ankara for collaboration with the Nazis and also for returning the occupied Western Armenia territories was intensely discussed by the Soviet leadership in 1945–1947.[16][17]

The Soviet military commanders told Nzhdeh that the idea of collaboration was interesting but in order to be able to discuss it in more details, Nzhdeh would have needed to travel to Moscow.[18] He was transferred to Bucharest and later to Moscow, where he was arrested and held in the Lubyanka prison.

After his arrest, Nzhdeh's wife and son were sent to exile from Sofia to Pavlikeni.

In November 1946, Nzhdeh was sent to Yerevan, Armenia, awaiting trial. At the end of his trial, on 24 April 1948, Nzhdeh was charged with "counterrevolutionary" activities in 1920–1921 and sentenced to 25 years of imprisonment (to begin in 1944).[19]

Life in prison and death

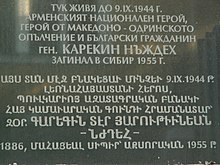

Commemorative plaque on the house of Nzhdeh in Sofia, where he was arrested in 1944

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

I'm Garegin Nzhdeh, a staunch enemy of the Bolshevism. I dedicated my own life to the struggle for freedom and independence of my people. I defended Zangezur from the Turks and the Turkish Bolsheviks. Is it possible that I will be afraid of your execution? Many have tried to threaten me, but they could not do anything.

— Garegin Nzhdeh to KGB Colonel Martiros Aghekyan[20]

In 1947 Nzhdeh proposed an initiative to the Soviet government. It would call for the foundation of a pan-Armenian military and political organization in the Armenian diaspora for the liberation of Western Armenia from Turkish control and its unification to Soviet Armenia. Despite the reputed great interest shown by the communist leaders to this initiative,[citation needed] the proposal was eventually refused.

Between 1948 and 1952 Nzhdeh was kept in Vladimir Prison, then until the summer of 1953 in a secret prison in Yerevan. According to his prison fellow Hovhannes Devedjian, Nzhdeh's transfer to Yerevan prison was related to an attempt to mediate between the Dashnaks and the Soviet leaders to create a collaborative atmosphere between the two sides. After long negotiations with the state security service of Soviet Armenia, Nzhdeh and Devejian prepared a letter in Yerevan prison (1953) addressed to the ARF leader Simon Vratsian, calling him for co-operation with the Soviets regarding the issue of the Armenian struggle against Turkey. However, the communist leaders in Moscow refused to send the letter and it only remained a latent document.

After receiving a telegram from the Soviet authorities, announcing his death, Nzhdeh's brother Levon left Yerevan for Vladimir to take care of his burial service. He received Nzhdeh's watch and clothing but was not allowed to take his personal writings, which would be published in Yerevan several years later. The authorities also did not allow the transfer of his body to Armenia. Levon Ter-Harutiunian conducted Nzhdeh's burial in Vladimir and wrote on his tombstone in Russian "Ter-Harutiunian Garegin Eghishevich (1886–1955)".

Legacy

Nzhdeh's tombstone at the Spitakavor Monastery

Garegin Nzhdeh's memorial in Kapan opened in 2003[21]

The monumental statue of Nzhdeh in Yerevan, erected in May 2016

On 31 August 1983, Nzhdeh's remains were secretly transferred from Vladimir to rest in Soviet Armenia. The process was fulfilled through the efforts of Pavel Ananyan, the husband of Nzhdeh's granddaughter, with the help of linguistics professor Varag Arakelyan and others, including Gurgen Armaghanyan, Garegin Mkhitaryan, Artsakh Buniatyan, and Zhora Barseghyan. On 7 October 1983, the right hand of Nzhdeh's body was placed on the slopes of Mount Khustup near Kozni fountain, as Nzhdeh had once expressed the wish "when you find me killed, bury my body at the top of Khustup to let me clearly view Kapan, Gndevaz, Goghtan and Geghvadzor...".

According to the participants at the funeral, the rest of Nzhdeh's body was kept in the cellar of Varag Arakelyan's house in the village of Kotayk until 9 May 1987, when it was secretly transferred to Vayots Dzor and buried in the churchyard of the 14th-century Spitakavor Surb Astvatsatsin Church near Yeghegnadzor.[22] Nzhdeh's gravestone was erected through the efforts of Paruyr Hayrikyan and Movses Gorgisyan on 17 June 1989, a day that later turned into an annual pilgrimage day to the monastery's graveyard.

Decades after his death, on 30 March 1992, Nzhdeh was rehabilitated by the supreme court of the newly independent Republic of Armenia.

On 26 April 2005 during the celebration of the 84th anniversary of the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, parts of Nzhdeh's body were taken from the Spitakavor Church to Khustup. Thus, Nzhdeh was reburied for the third time, finally to rest on the slopes of Mount Khustup near Nzhdeh's memorial in Kapan.[23]

In March 2010, Nzhdeh was selected as the "National pride and the most outstanding figure"[24] of Armenians throughout the history by the voters of "We are Armenians" TV project launched by "Hay TV" and broadcast as well by the Public Television of Armenia (H1).[25]

An avenue, a large square, and a nearby metro station in Yerevan are named after Garegin Nzhdeh. A village in the southern Syunik Province of Armenia is also named after Nzhdeh.

Awards

| Country | Award | Year | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Order of Bravery | For Bravery | 16 November 1912 | ||

Order of St. Vladimir | 3rd class | 1915, 1918 | ||

Order of St. Anna | 4th class | 1915 | ||

Cross of St. George | 3rd class | 1916 | ||

Cross of St. George | 2nd class | 1916 | ||

Works

- "The Pantheon of Dashnaktsutyun", Alexandrapol 1917

- "Calls of Khustup", Goris 1921

- "My Speech – Why I Fought against the Soviet Army", Bucharest 1923

- "Some Pages from my Diary", Cairo 1924

- "Open Letters to the Armenian Intelligentsia", Sofia 1926 and Beirut 1929

- "The Struggle of Sons against Fathers", Thessaloniki 1927

- "The Motive of the Soul of the Nation", Sofia 1932

- "The American Armenians – The Tribe and its Gutter", Sofia 1935

- "My Answer", Sofia 1937

- "Autobiography", Sofia 1944

- "Thoughts – Notes from Jail", Yerevan 1993

Books

Selected Works of Garegin Nzhdeh, translated by Eduard Danielyan, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 978-0-9783096-0-2, 2011, 164 pp.

Portrayal

- Books

The Battle of Lernahayastan, by Vartan Kevorkian, Bucharest 1923

Nzhdeh, by Avo, Beirut 1968

The Memories of a Prisoner, by Armen Sevan (Hovhannes Devedjian), Buenos Aires 1970

Garegin Nzhdeh, published in the memory of his 110th anniversary, Yerevan 1996

Garegin Nzhdeh: Analecta, contains Nzhdeh's ideologies, thoughts, letters, speeches and other writings, Yerevan 2006

Nzhdeh: The Complete Biography, by Rafael Hambardzumian, Yerevan 2007

Selected Works of Garegin Nzhdeh English Translation and Commentaries by Eduard Danielyan, Doctor of History; Publisher: "Nakhijevan" Institute of Canada, Montreal, 2011.

- Films

The Path of the Eternal, by Arthur Babayan and Armen Tevanian.

Garegin Nzhdeh, a documentary film within the Why Is the Past Still Making Noise? series, produced in 2011 by the Public TV of Armenia.

Garegin Nzhdeh, film premiered on 28 January 2013 in Yerevan's Moscow Cinema, produced by HK Productions.

References

^ Harutyunyan, Arus (2009). Contesting National Identities in an Ethnically Homogeneous State: The Case of Armenian Democratization. Western Michigan University. p. 61. ISBN 9781109120127.

^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: from kings and priests to merchants and commissars. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 301. ISBN 9780231139267.

^ Chorbajian, Levon (1994). The Caucasian Knot: The History & Geopolitics of Nagorno-Karabagh. London: Zed Books. p. 134. ISBN 9781856492881.But it is undeniable that if Zangezur has since been an integral part of Soviet Armenia, it was Nzhdeh who made it possible.

^ Panossian, Razmik (2006). The Armenians: From Kings and Priests to Merchants and Commissars. London: Columbia University Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780231511339.

^ Thomas de Waal. Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press, 2015, p. 112

^ Smele, Jonathan D. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916-1926. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 795. ISBN 1442252812.

^ Հայրապետյան, Միքայել (15 July 2008). "Nzhdehs, go home" (in Armenian). "Հայկական ժամանակ". Retrieved 11 August 2012.

^ Македоно-одринското опълчение 1912–1913. Личен състав по документи на Дирекция "Централен военен архив", София 2006, с. 521 (Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps. Staff according to documents from Directorate Central Military Archives, Sofia 2006, p. 521)

^ Hovhanissian, Richard G. (1997) The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times. New York. St. Martin's Press, 299

^ ՆԺԴԵՀԻ ԿՅԱՆՔԸ, ԳՈՐԾՈՒՆԵՈՒԹՅՈՒՆԸ ԵՎ ԶԱՆԳԵԶՈՒՐԻ ՃԱԿԱՏԱԳԻՐԸ (in Armenian). Syunik.wordpress.com. 26 September 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

^ "Garegin Nzhdeh biography". Nzhdeh.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

^ The Armenian Cause Encyclopedia, Yerevan 1996, article:Garegin Nzhdeh, p. 356

^ Михайлов, Иван. Карекин Нъждех, в. Македонска трибуна, г. 31, бр. 1601, 21 ноември 1957 (Mihaylov, Ivan. Garegin Nzhdeh, Macedonian Tribune, N 1601, 21 November 1957)

^ Kurt Mehner, Germany. Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, Bundesarchiv (Germany). Militärarchiv, Arbeitskreis für Wehrforschung. Die Geheimen Tagesberichte der Deutschen Wehrmachtführung im Zweiten Weltkrieg, 1939–1945: 1. Dezember 1943–29. Februar 1944. p. 51 (in German).

^ Documentary about Garegin Nzhdeh, 1h.06.min on YouTube

^ The Turkish – American Relationship Between 1947 and 2003, Nazih Uslu, p. 68

^ "Present at the creation: my years in the State Department", Dean Acheson, pp. 199–200

^ A Documentary about Garegin Nzhdeh, 1h07min on YouTube

^ "Russia Unhappy With Armenian Statue". Azatutyun. 28 May 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

^ Гарегин Нжде и КГБ (in Russian). Bvahan.com. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

^ "Karekin Njhdeh Monument in Kapan". Asbarez. 25 August 2000. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

^ Nzhdeh after his death

^ A1plus.am NZHDEH WAS RE-BURIED Retrieved 27 April 2005

^ Menqhayenq.com – We Are Armenians:About Project Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

^ Menqhayenq.com – We Are Armenians:Rating Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

External links

About Nzhdeh in Armenian in website nzhde.com

Garegin Nzhdeh Movie 2013 in website kkkino.ru