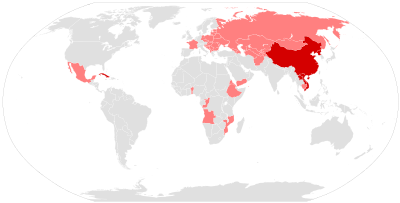

State atheism

Countries that formerly practiced state atheism

Countries that currently practice state atheism

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Atheism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

Types

| ||||||||

Arguments for atheism Against God's existence

| ||||||||

People

| ||||||||

Related stances

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Part of a series on | |||||

| Irreligion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Irreligion

| |||||

Atheism

| |||||

Agnosticism

| |||||

Nontheism

| |||||

Naturalism

| |||||

People

| |||||

Books

| |||||

Secularist organizations

| |||||

Related topics

| |||||

| |||||

| Freedom of religion | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Concepts

| ||||||||||||

Status by country

| ||||||||||||

Religious persecution

| ||||||||||||

Religion portal | ||||||||||||

State atheism is the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes, particularly associated with Soviet systems.[1] In contrast, a secular state purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion.[2] State atheism may refer to a government's anti-clericalism, which opposes religious institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, including the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen.[3][4][1]

The majority of Marxist–Leninist states followed similar policies from 1917.[3][5][6][7][8][9] The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (1917–1991), and the Soviet Union (1922–1991) more broadly, had a long history of state atheism, whereby those seeking social success generally had to profess atheism and to stay away from houses of worship; this trend became especially militant during the middle Stalinist era from 1929 to 1939. The Soviet Union attempted to suppress public religious expression over wide areas of its influence, including places such as central Asia. Currently, only China, Cuba, North Korea and Vietnam are officially atheist.

Contents

1 Communist states

1.1 Soviet Union

1.2 Albania

1.3 Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge

1.4 China

1.5 Cuba

1.6 East Germany

1.7 North Korea

1.8 Mongolia

1.9 Vietnam

2 Non-Communist states

2.1 Revolutionary Mexico

3 Human rights

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

Communist states

A communist state, in popular usage, is a state with a form of government characterized by one-party rule or dominant-party rule of a communist party and a professed allegiance to a Leninist or Marxist–Leninist communist ideology as the guiding principle of the state. The founder and primary theorist of Marxism, the nineteenth-century German thinker Karl Marx, had an ambivalent attitude toward religion, viewing it primarily as "the opium of the people" that had been used by the ruling classes to give the working classes false hope for millennia, whilst at the same time recognizing it as a form of protest by the working classes against their poor economic conditions.[10] In the Marxist–Leninist interpretation of Marxist theory, developed primarily by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, religion is seen as negative to human development, and communist states that follow a Marxist–Leninist variant are atheistic and explicitly antireligious.[11] Lenin states:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Religion is the opiate of the people: this saying of Marx is the cornerstone of the entire ideology of Marxism about religion. All modern religions and churches, all and of every kind of religious organizations are always considered by Marxism as the organs of bourgeois reaction, used for the protection of the exploitation and the stupefaction of the working class.[11]

Although Marx[12] and Lenin[13][citation not found] were both atheists, several religious communist groups exist, including Christian communists.

Julian Baggini devotes a chapter of his book Atheism: A Very Short Introduction to discussion of 20th century political systems, including communism and political repression in the Soviet Union.[14] Baggini argues that "Soviet communism, with its active oppression of religion, is a distortion of original Marxist communism, which did not advocate oppression of the religious." Baggini goes on to argue that "Fundamentalism is a danger in any belief system" and that "Atheism's most authentic political expression... takes the form of state secularism, not state atheism."

Soviet Union

USSR. 1922 issue of the Bezbozhnik (The Godless) magazine. By 1934, 28% of Eastern Orthodox churches, 42% of Muslim mosques and 52% of Jewish synagogues were shut down in the USSR.[15]

State atheism, (gosateizm, a syllabic abbreviation of "state" (gosudarstvo) and "atheism" (ateizm)), was a major goal of the official Soviet ideology.[16] To that end, the regime expropriated church property, publication of information against religious beliefs and the official promotion of anti-religious materials in the education system.

After the Russian Civil War, the state used its resources to stop the implanting of religious beliefs in nonbelievers and remove "prerevolutionary remnants" that still existed.[16] The Bolsheviks were particularly hostile toward the Russian Orthodox Church (which supported the White Movement during the Russian Civil War) and saw it as a supporter of Tsarist autocracy.[17] During a process of collectivization of land, Orthodox priests distributed pamphlets declaring that the Soviet regime was the Antichrist coming to place "the Devil's mark" on the peasants, and encouraged them to resist the government.[17]Political repression was widespread in the Soviet Union, and while religious persecution was applied to most religions,[18] the regime's anti-religious campaigns were often directed against specific religions based on state interests, that varied over time. The attitude in the Soviet Union toward religion varied from a total ban on some religions to official support of others.

From the late 1920s to the late 1930s, such organizations as the League of Militant Atheists ridiculed all religions and harassed believers.[19] Anti-religious and atheistic propaganda was implemented into every portion of soviet life: in schools, communist organizations such as the Young Pioneer Organization, and the media. Though Lenin originally introduced the Gregorian calendar to the Soviets, subsequent efforts to reorganise the week to improve worker productivity saw the introduction of the Soviet calendar, which had the side-effect that a "holiday will seldom fall on Sunday".[20]

Within about a year of the revolution, the state expropriated all church property, including the churches themselves, and in the period from 1922 to 1926, 28 Russian Orthodox bishops and more than 1,200 priests were killed (a much greater number was subjected to persecution).[18] Most seminaries were closed, and publication of religious writing was banned.[18] The Russian Orthodox Church, which had 54,000 parishes before World War I, was reduced to 500 by 1940.[18] A meeting of the Antireligious Commission of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) that occurred on 23 May 1929 estimated the portion of believers in the USSR at 80 percent, though this percentage may be understated to prove the successfulness of the struggle with religion.[21]

Despite the Soviet Union's attempts to eliminate religion,[16][22][23] other former USSR and anti-religious nations, such as Armenia,[24]Kazakhstan,[25]Uzbekistan,[26]Turkmenistan,[27]Kyrgyzstan,[28]Tajikistan,[29]Belarus,[30][31]Moldova,[32] and Georgia[33] have high religious populations.[34] Author Niels Christian Nielsen has written that the post-Soviet population in areas which were formerly predominantly Orthodox are now "nearly illiterate regarding religion", almost completely lacking the intellectual or philosophical aspects of their faith and having almost no knowledge of other faiths.[35] Nonetheless, their knowledge of their faith and the faith of others notwithstanding, many post-Soviet populations have a large presence of religious followers.

Today in the Russian Federation, approximately 100 million citizens consider themselves Russian Orthodox Christians, amounting to 70% of the population, although the Church claims a membership of 80 million.[36][37][38] According to the CIA Factbook, however, only 17% to 22% of the population is now Christian.[39] According to a poll by the Russian Public Opinion Research Center, 63% of respondents considered themselves Russian Orthodox, 6% of respondents considered themselves Muslim and less than 1% considered themselves either Buddhist, Catholic, Protestant or Jewish. Another 12% said they believe in God, but did not practice any religion, and 16% said they are non-believers.[40] In Ukraine, 96.1% of the Ukrainian population is Christian.[41] In Lithuania, the only Catholic country which was once a Soviet republic,[42] a 2005 report stated that 79% of Lithuanians belonged to the Roman Catholic Church.[43]

Albania

Religion in Albania was subordinated to the interests of nationalism during periods of national revival, when it was identified as foreign predation to Albanian culture. During the late nineteenth century, and also when Albania became a state, religions were suppressed in order to better unify Albanians. This nationalism was also used to justify the communist stance of state atheism from 1967 to 1991.[44] The Agrarian Reform Law of August 1945 nationalized most property of religious institutions, including the estates of mosques, monasteries, orders, and dioceses. Many clergy and believers were tried and some were executed. All foreign Roman Catholic priests, monks, and nuns were expelled in 1946.[45]

Religious communities or branches that had their headquarters outside the country, such as the Jesuit and Franciscan orders, were henceforth ordered to terminate their activities in Albania. Religious institutions were forbidden to have anything to do with the education of the young, because that had been made the exclusive province of the state. All religious communities were prohibited from owning real estate and from operating philanthropic and welfare institutions and hospitals.

Although there were tactical variations in Enver Hoxha's approach to each of the major denominations, his overarching objective was the eventual destruction of all organized religion in Albania. Between 1945 and 1953, the number of priests was reduced drastically and the number of Roman Catholic churches was decreased from 253 to 100, and all Catholics were stigmatized as fascists.[45]

The campaign against religion peaked in the 1960s. Beginning in February 1967 the Albanian authorities launched a campaign to eliminate religious life in Albania. Despite complaints, even by APL members, all churches, mosques, monasteries, and other religious institutions were either closed down or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, or workshops by the end of 1967.[46] By May 1967, religious institutions had been forced to relinquish all 2,169 churches, mosques, cloisters, and shrines in Albania, many of which were converted into cultural centers for young people. As the literary monthly Nendori reported the event, the youth had thus "created the first atheist nation in the world."[45]

Clerics were publicly vilified and humiliated, their vestments were taken and desecrated. More than 200 clerics of various faiths were imprisoned, others were forced to seek work in either industry or agriculture, and some were executed or starved to death. The cloister of the Franciscan order in Shkodër was set on fire, which resulted in the death of four elderly monks.[45]

Article 37 of the Albanian Constitution of 1976 stipulated, "The state recognizes no religion, and supports atheistic propaganda in order to implant a scientific materialistic world outlook in people.",[47][3] and the penal code of 1977 imposed prison sentences of three to ten years for "religious propaganda and the production, distribution, or storage of religious literature."[citation needed] A new decree that in effect targeted Albanians with Muslim and Christian names, stipulating that citizens whose names did not conform to "the political, ideological, or moral standards of the state" were to change them.[citation needed] It was also decreed that towns and villages with religious names must be renamed.[citation needed] Hoxha's brutal antireligious campaign succeeded in eradicating formal worship, but some Albanians continued to practice their faith clandestinely, risking severe punishment.[citation needed] Individuals caught with Bibles, Qurans, icons, or other religious objects faced long prison sentences. Religious weddings were prohibited.[citation needed]

Parents were afraid to pass on their faith, for fear that their children would tell others. Officials tried to entrap practicing Christians and Muslims during religious fasts, such as Lent and Ramadan, by distributing dairy products and other forbidden foods in school and at work, and then publicly denouncing those who refused the food. Those clergy who conducted secret services were incarcerated.[45] Catholic priest Shtjefen Kurti had been executed for secretly baptizing a child in Shkodër in 1972.[48]

The article was interpreted by Danes as violating The United Nations Charter (chapter 9, article 55) which declares that religious freedom is an inalienable human right. The first time that the question came before the United Nations' Commission on Human Rights at Geneva was as late as 7 March 1983. A delegation from Denmark got its protest over Albania's violation of religious liberty placed on the agenda of the thirty-ninth meeting of the commission, item 25, reading, "Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination based on Religion or Belief.", and on 20 July 1984 a member of the Danish Parliament inserted an article into one of Denmark's major newspapers protesting the violation of religious freedom in Albania.

The 1998 Constitution of Albania defined the country as a parliamentary republic, and established personal and political rights and freedoms, including protection against coercion in matters of religious belief.[49][50] Albania is a member state of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation,[49] and the 2011 census found that 58.79% of Albanians adhere to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country. The majority of Albanian Muslims are secular Sunnis along with a significant Bektashi Shia minority. Christianity is practiced by 16.99% of the population, making it the 2nd largest religion in the country. The remaining population is either irreligious or belongs to other religious groups.[51] Before World War II, there was given a distribution of 70% Muslims, 20% Eastern Orthodox, and 10% Roman Catholics.[52] Today, Gallup Global Reports 2010 shows that religion plays a role in the lives of 39% of Albanians, and ranks Albania the thirteenth least religious country in the world.[53] The U.S. state department reports that in 2013, "There were no reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice."[50]

Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge

Khmer Rouge bullet holes left at Angkor Wat temple

The Khmer Rouge actively persecuted Buddhists during their reign from 1975 to 1979.[54] Buddhist institutions and temples were destroyed and Buddhist monks and teachers were killed in large numbers.[55] A third of the nation's monasteries were destroyed along with numerous holy texts and items of high artistic quality. 25,000 Buddhist monks were massacred by the regime,[56] which was officially an atheist state.[7] The persecution was undertaken because Pol Pot believed that Buddhism was "a decadent affectation". He sought to eliminate Buddhism's 1,500-year-old mark on Cambodia.[56]

Religion was also banned, and the repression of adherents of Islam, Christianity, and Buddhism was extensive. And according to Ben Kiernan, the "fiercest extermination campaign was directed against the ethnic Cham Muslim minority".[57]

China

China is an officially atheist state,[58] which has promoted atheism throughout the country.[59][6] In April 2016, the General Secretary, Xi Jinping, stated that members of the Communist Party of China must be "unyielding Marxist atheists" while in the same month, a government-sanctioned demolition work crew drove a bulldozer over two Chinese Christians who protested the demolition of their church by refusing to step aside.[60]

Traditionally, a large segment of the Chinese population took part in Chinese folk religions[61] and Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism had played a significant role in the everyday lives of ordinary people.[62][63][64] After the 1949 Chinese Revolution, China began a period of rule by the Communist Party of China.[65][66] For much of its early history, that government maintained under Marxist thought that religion would ultimately disappear, and characterized it as emblematic of feudalism and foreign colonialism.

During the Cultural Revolution, student vigilantes known as Red Guards converted religious buildings for secular use or destroyed them. This attitude, however, relaxed considerably in the late 1970s, with the reform and opening up period. The 1978 Constitution of the People's Republic of China guaranteed freedom of religion with a number of restrictions. Since then, there has been a massive program to rebuild Buddhist and Taoist temples that were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution.

The Communist Party has said that religious belief and membership are incompatible.[67] However, the state is not allowed to force ordinary citizens to become atheists.[68]China's five officially sanctioned religious organizations are the Buddhist Association of China, Chinese Taoist Association, Islamic Association of China, Three-Self Patriotic Movement and Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. These groups are afforded a degree of protection, but are subject to restrictions and controls under the State Administration for Religious Affairs. Unregistered religious groups face varying degrees of harassment.[69] The constitution permits what is called "normal religious activities," so long as they do not involve the use of religion to "engage in activities that disrupt social order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious organizations and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign dominance."[68]

Article 36 of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China of 1982 specifies that:

Citizens of the People's Republic of China enjoy freedom of religious belief. No state organ, public organization or individual may compel citizens to believe in, or not to believe in, any religion; nor may they discriminate against citizens who believe in, or do not believe in, any religion. The state protects normal religious activities. No one may make use of religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination.[70]

Most people report no organized religious affiliation; however, people with a belief in folk traditions and spiritual beliefs, such as ancestor veneration and feng shui, along with informal ties to local temples and unofficial house churches number in the hundreds of millions. The United States Department of State, in its annual report on International Religious Freedom,[71] provides statistics about organized religions. In 2007 it reported the following (citing the Government's 1997 report on Religious Freedom and 2005 White Paper on religion):[72]

- Buddhists 8%.

- Taoists, unknown as a percentage partly because it is fused along with Confucianism and Buddhism.

- Muslims, 1%, with more than 20,000 Imams. Other estimates state at least 1%.

- Christians, Protestants at least 2%. Catholics, about 1%.

Statistics relating to Buddhism and religious Taoism are to some degree incomparable with statistics for Islam and Christianity. This is due to the traditional Chinese belief system which blends Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, so that a person who follows a traditional belief system would not necessarily identify him- or herself as exclusively Buddhist or Taoist, despite attending Buddhist or Taoist places of worship. According to Peter Ng, Professor of the Department of Religion at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, as of 2002[update], 95% of Chinese were religious in some way if religion is considered to include traditional folk practices such as burning incense for gods or ancestors at life-cycle or seasonal festivals, fortune telling and related customary practices.[73][74]

The U.S. State Department has designated China as a "country of particular concern" since 1999,[75][76] in part, due to the scenario of Uighur Muslims and Tibetan Buddhists. Freedom House classifies Tibet and Xinjiang as regions of particular repression of religion, due to concerns of separatist activity.[77][78][79][80][81]Heiner Bielefeldt, the UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief says that China's actions against the Uighurs are "a major problem".[82] The Chinese government has protested the report, saying the country has "ample" religious freedom.[83]

Cuba

Until 1992,[84] Cuba was officially an atheist state.[8][85]

In August 1960, several bishops signed a joint pastoral letter condemning communism and declaring it incompatible with Catholicism, and calling on Catholics to reject it.[86]Fidel Castro gave a four-hour long speech the next day, condemning priests who serve "great wealth" and using fears of Falangist influence in order to attack Spanish born priests, declaring "There is no doubt that Franco has a sizeable group of fascist priests in Cuba."

Originally more tolerant of religion, the Cuban government began arresting many believers and shutting down religious schools after the Bay of Pigs invasion. Its prisons were being filled with clergy since the 1960s.[87] In 1961 The Cuban government confiscated Catholic schools, including the Jesuit school that Fidel Castro had attended. In 1965 it exiled two hundred priests.[88]

In 1976 the Constitution of Cuba added a clause stating that the "socialist state...bases its activity on, and educates the people in, the scientific materialist concept of the universe". In

1992, the Dissolution of the Soviet Union led the country to declare itself a secular state,[89][90] and Catholic groups have worked to advance the Cuban thaw. In January 1998, Pope John Paul II paid a historic visit to the island, invited by the Cuban government and the Catholic Church in Cuba. The pope criticized the US embargo during his visit.[91]Pope Benedict XVI visited Cuba in 2012 and Pope Francis visited Cuba in 2015.[92][93][94][95] The Cuban government continued hostile actions against religious groups; in 2015 alone, the Castro régime ordered the closure or demolition of over 100 Pentecostal, Methodist, and Baptist parishes.[96]

East Germany

East Germany was an atheist state.[97]

As of 2012[update] the area of the former German Democratic Republic was the least religious region in the world.[98][99][100]

North Korea

Although the North Korean constitution states that freedom of religion is permitted,[101] free religious activities no longer exist in North Korea, because the government sponsors religious groups only to create an illusion of religious freedom.[102][103][104] The North Korean government's Juche ideology has been described as "state-sanctioned atheism".[9] After 1,500 churches were destroyed during the rule of Kim Il Sung from 1948 to 1994, three churches were built in Pyongyang to deflect human rights criticism.[102]

The North Korean government promotes the cult of personality of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung, described as a political religion, as well as the Juche ideology, based on Korean ultranationalism, which calls on people to "avoid spiritual deference to outside influences", which was interpreted as including religion originating outside of Korea.[105][68]

North Korea has been designated a "country of particular concern" by the U.S. State Department since 2001 due to its religious freedom violations.[106][107]Cardinal Nicolas Cheong Jin-suk has said that, "There's no knowledge of priests surviving persecution that came in the late forties, when 166 priests and religious were killed or kidnapped," which includes the Roman Catholic bishop of Pyongyang, Francis Hong Yong-ho.[108] On November 2013, the repression against religious people led to the public execution of 80 people, some of them for possessing Bibles.[105][106][109]

Mongolia

In the Mongolian People's Republic, after the invasion by Japanese troops of 1936, the Soviet Union deployed its troops in 1937, undertaking an offensive against the Buddhist religion. In parallel, a Soviet-style purge campaign was launched in the Communist Party and the Mongolian army. The Mongol leader at that time was Khorloogiin Choibalsan, follower of Joseph Stalin, who emulated many of the policies that Stalin developed in the Soviet Union. The purges succeeded in virtually eliminating Lamaism and cost an estimated thirty to thirty-five thousand lives.[citation needed]

Vietnam

Officially, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is an atheist state as declared by its communist government.[110]

Non-Communist states

Revolutionary Mexico

Articles 3, 5, 24, 27, and 130 of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 as originally enacted were anticlerical and restricted religious freedoms.[111] At first the anticlerical provisions were seldom enforced, but when President Plutarco Elías Calles took office in 1924, he enforced the provisions strictly.[111] Calles' Mexico has been characterized as an atheist state[112] and his program as being one to eradicate religion in Mexico.[113]

All religions had their properties expropriated, and these became part of government wealth. There was an expulsion of foreign clergy and the seizure of Church properties.[114] Article 27 prohibited any future acquisition of such property by the churches, and prohibited religious corporations and ministers from

establishing or directing primary schools.[114] This second prohibition was sometimes interpreted to mean that the Church could not give religious instruction to children within the churches on Sundays, seen as destroying the ability of Catholics to be educated in their own religion.[115]

The Constitution of 1917 also forbade the existence of monastic orders (article 5) and any religious activity outside of church buildings (now owned by the government), and mandated that such religious activity would be overseen by the government (article 24).[114]

On June 14, 1926, President Calles enacted anticlerical legislation known formally as The Law Reforming the Penal Code and unofficially as the Calles Law.[116] His anti-Catholic actions included outlawing religious orders, depriving the Church of property rights and depriving the clergy of civil liberties, including their right to a trial by jury (in cases involving anti-clerical laws) and the right to vote.[116][117] Catholic antipathy towards Calles was enhanced because of his vocal atheism.[118] He was also a Freemason.[119] Regarding this period, recent President Vicente Fox stated, "After 1917, Mexico was led by anti-Catholic Freemasons who tried to evoke the anticlerical spirit of popular indigenous President Benito Juárez of the 1880s. But the military dictators of the 1920s were a more savage lot than Juarez."[120]

Cristeros hanged in Jalisco.

Due to the strict enforcement of anti-clerical laws, people in strongly Catholic states, especially Jalisco, Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Colima and Michoacán, began to oppose him, and this opposition led to the Cristero War from 1926 to 1929, which was characterized by brutal atrocities on both sides. Some Cristeros applied terrorist tactics, while the Mexican government persecuted the clergy, killing suspected Cristeros and supporters and often retaliating against innocent individuals.[121] On May 28, 1926, Calles was awarded a medal of merit from the head of Mexico's Scottish rite of Freemasonry for his actions against the Catholics.[122]

A truce was negotiated with the assistance of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Whitney Morrow.[123] Calles, however, did not abide by the terms of the truce – in violation of its terms, he had approximately 500 Cristero leaders and 5,000 other Cristeros shot, frequently in their homes in front of their spouses and children.[123] Particularly offensive to Catholics after the supposed truce was Calles' insistence on a complete state monopoly on education, suppressing all Catholic education and introducing "socialist" education in its place: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth.".[124] The persecution continued as Calles maintained control under his Maximato and did not relent until 1940, when President Manuel Ávila Camacho, a believing Catholic, took office.[124] This attempt to indoctrinate the youth in atheism was begun in 1934 by amending Article 3 to the Mexican Constitution to eradicate religion by mandating "socialist education", which "in addition to removing all religious doctrine" would "combat fanaticism and prejudices", "build[ing] in the youth a rational and exact concept of the universe and of social life".[111] In 1946 this "socialist education" was removed from the constitution and the document returned to the less egregious generalized secular education.

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed.[124] Where there were 4,500 priests operating within the country before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion, and assassination.[124][125] By 1935, 17 states had no priest at all.[126]

Human rights

Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is designed to protect the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion. In 1993, the UN's human rights committee declared that article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights "protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief."[127] The committee further stated that "the freedom to have or to adopt a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views." Signatories to the convention are barred from "the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers" to recant their beliefs or convert.[105] Despite this, as of 2009[update] minority religions were still being persecuted in many parts of the world.[128][129]

Theodore Roosevelt condemned the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, establishing a history of U.S. presidents commenting on the internal religious liberty of foreign countries.[130] In Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1941 State of the Union address, he outlined Four Freedoms, including Freedom of worship, that would be foundation for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and future U.S. diplomatic efforts.[130]Jimmy Carter asked Deng Xiaoping to improve religious freedom in China, and Ronald Reagan told US Embassy staff in Moscow to help Jews harassed by the Soviet authorities.[130][131]Bill Clinton established the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom with the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, in order to use diplomacy to promote religious liberty in repressive states.[132]

See also

- Antireligion

- Civil religion

- Communism and religion

- Freedom of religion

- Reign of Terror

- Religion in China

- Religion in East Germany

- Religion in the Soviet Union

- Religious persecution

- Religion of Humanity

- Religion in Russia

- Militant atheism

- Scientism

- Society of the Godless

- Staatssekretär für Kirchenfragen

- State religion

- War in the Vendée

Notes

^ ab Bullivant, Stephen; Lee, Lois (2016). A Dictionary of Atheism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191816819.State Atheism is the name given to the incorporation of positive atheism or non-theism into political regimes, particularly associated with Soviet systems. State Atheisms have tended to be as much anti-clerical and anti-religious as they are anti-theist, and typically place heavy restrictions on acts of religious organization and the practice of religion.

.mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law : Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance. Brill Academic/Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 9789004181489.Although the historical underlying incentives that accompanied the establishment of a secular state may have been characterized by criticism of certain religious doctrines or practices, presently a state of secularity in itself does not necessarily reflect value judgements about religion. In other words, state secularism does not come down to an official rejection of religion. State secularism denotes an intention on the part of the state to not affiliate itself with religion, to not consider itself a priori bound by religious principles (unless they are reformulated into secular state laws) and to not seek to justify its actions by invoking religion. Such a state of secularity denotes official impartiality in matters of religion rather than official irreligiosity. By contrast, secularism as a philosophical notion can indeed be construed as an ideological defense of the secular cause, which might include criticism of or scepticism towards religion. Thus, states that are 'ideologically secular' and that declare secular world-views the official state doctrine give evidence, explicitly or by implication, of judgements about the value of religion within society. Most versions of state communism, for instance, embrace Marxist criticism of religion.

^ abc Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law : Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance. Brill Academic/Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 140–141. ISBN 9789004181489.Before the end of the Cold War, many Communist States did not shy away from being openly hostile to religion. In most instances, communist ideology translated unperturbedly into state atheism, which, in turn, triggered measures aimed at the eradication of religion. As much was acknowledged by some Communist Constitutions. The 1976 Constitution of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, for instance, was firmly based on a Marxist dismissal of religion as the opiate of the masses. It provided: "The state recognizes no religion of any kind and supports and develops the atheist view so as to ingrain in to the people the scientific and materialistic world-view."

^ Franken, Leni; Loobuyck, Patrick (2011). Religious Education in a Plural, Secularised Society. A Paradigm Shift. Waxmann Verlag. p. 152. ISBN 9783830975434.In this model, atheism is a state doctrine. Instead, it is regarded as an official state policy, aiming to eradicate all sympathy for religious ideas, and the idea that God exists in particular. The adherents of political atheism make a plea for an atheist state that has to foster atheist convictions in its citizenry.

^ Borowik, Irena; Ancic, Branko; Tyrala, Radoslaw. "39.Central And Eastern Europe". In Ruse, Michael; Bullivant, Stephen. Oxford Handbook of Atheism. Oxford University Press. p. 626. ISBN 0198745079.There have been only a few comparative analyses of atheism carried out in the CEE region. One of the few attempts of this kind is that undertaken by Sinita Zrinkak (see 2004). Comparing different types of generational responses to atheism in several CEE countries, on the basis of studies carried out in these countries and based on data from the EVS, he distinguishes three groups of countries in the region. The first group comprises countries in which state atheism had the most severe consequences... This group includes such countries as Estonia, Latvia, Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Bulgaria.

^ ab Eller, Jack David (2014). Introducing Anthropology of Religion: Culture to the Ultimate. Routledge. p. 254. ISBN 1138024910.After the communist revolution of 1949, the People's Republic of China adopted a policy of official state atheism. Based on Marxist thinking that religion is class exploitation and false consciousness, the communist regime suppressed religion, "re-educated" believers and religious leaders, and destroyed religious buildings or converted them to non-religious uses.

^ ab Wessinger, Catherine (2000). Millennialism, Persecution, and Violence: Historical Cases. Syracuse University Press. p. 282. ISBN 9780815628095.Democratic Kampuchea was officially an atheist state, and the persecution of religion by the Khmer Rouge was matched in severity only by the persecution of religion in the communist states of Albania and North Korea, so there were not any direct historical continuities of Buddhism into the Democratic Kampuchea era.

^ ab Freeing God's Children: The Unlikely Alliance for Global Human Rights. Rowman & Littlefield.Cuba is the only country in the Americas that has attempted to impose state atheism, and since the 1960s onward its jails have been filled with pastors and other believers.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ ab Hertzke (2006):44

^ Raines, John. 2002. "Introduction". Marx on Religion (Marx, Karl). Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Page 05-06.

^ ab

Lenin, V. I. "About the attitude of the working party toward the religion". Collected works, v. 17, p.41. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

^ Nicolaievsky & Maenchen-Helfen 1976, pp. 38–45[citation not found]; Wheen 2001, p. 34[citation not found]; McLellan 2006, pp. 32–33, 37[citation not found].

^ Fischer 1964, p. 552; Leggett 1981, p. 308; Sandle 1999, p. 126; Read 2005, pp. 238–239; Ryan 2012, pp. 176, 182.

^ Julian Baggini (26 June 2003). Atheism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. pp. 82–90. ISBN 978-0-19-280424-2.

^ "Religions attacked in the USSR". Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved 2005-07-22.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) (Beyond the Pale)

^ abc Kowalewski, David (1980). "Protest for Religious Rights in the USSR: Characteristics and Consequences". Russian Review. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review. 39 (4): 426–441. doi:10.2307/128810. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 128810.

^ ab Sheila Fitzpatrick (1996). Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village After Collectivization. Oxford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-19-510459-2.

^ abcd Country Studies: Russia-The Russian Orthodox Church U.S. Library of Congress, Accessed Apr. 3, 2008

^ Richard Overy (2006), The Dictators: Hitler's Germany, Stalin's Russia, p. 271

ISBN 0-393-02030-4

^ "Staggerers Unstaggered". Time magazine. December 7, 1931. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

^ Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer (2009). Religion and Politics in Russia: A Reader. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-7656-2415-4.

^ Sabrina Petra Ramet, Ed., Religious Policy in the Soviet Union. Cambridge University Press (1993). P 4

^ John Anderson, Religion, State and Politics in the Soviet Union and Successor States, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp 3

^ "The Armenian Apostolic Church (World Council of Churches)".

^ International Religious Freedom Report 2009 – Kazakhstan U.S. Department of State. 2009-10-26. Retrieved on 2009-11-05.

^ "Uzbekistan". State.gov. 2009-10-16. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov.

^ "Kyrgyzstan". State.gov. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

^ "Background Note: Tajikistan". State.gov. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

^ "Belarus Religion Stats: NationMaster.com". nationmaster.com.

^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov.

^ "Moldova Religion Stats". nationmaster.com.

^ "Georgia Religion Stats". nationmaster.com.

^ Miller, Tracy, ed. (October 2009). "Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Muslim Population" (PDF). Pew Research Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

^ Nielsen, Niels Christian, Jr., Christianity After Communism, p. 77-78, Westview Press 1998

^ Page, Jeremy (2005-08-05). "The rise of Russian Muslims worries Orthodox Church". The Times. London. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

^ "Russia". U.S. Department of State.

^ "Russia". Retrieved 2008-04-08.

^ Cole, Ethan Gorbachev Dispels 'Closet Christian' Rumors; Says He is Atheist Christian Post, Mar. 24, 2008

^ Опубликована подробная сравнительная статистика религиозности в России и Польше (in Russian). religare.ru. 6 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

^ "Ukraine Religion Stats". nationmaster.com.

^ Olsen, Brad (2007). Sacred Places Europe: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-888729-12-2.

^ Department of Statistics to the Government of the Republic of Lithuania. "Population by Religious Confession, census". Archived from the original on 2006-10-01.. Updated in 2005.

^ Representations of Place: Albania, Derek R. Hall, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 165, No. 2, The Changing Meaning of Place in Post-Socialist Eastern Europe: Commodification, Perception and Environment (Jul., 1999), pp. 161–172, Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) "the perception that religion symbolized foreign (Italian, Greek and Turkish) predation was used to justify the communists' stance of state atheism (1967-1991)."

^ abcde "Albania - Hoxha's Antireligious Campaign". country-data.com.

^ "Albania - The Cultural and Ideological Revolution". country-data.com.

^ C. Education, Science, Culture, The Albanian Constitution of 1976.

^ Sinishta, G., 1976. The Fulfilled Promise: A Documentary Account of Religious Persecution in Albania. Albanian Catholic Information Center, Santa Clara.

^ ab "The Religion-State Relationship and the Right to Freedom of Religion or Belief: A Comparative Textual Analysis of the Constitutions of Majority Muslim Countries and Other OIC Members" (PDF). U.S. COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM. 2012.

^ ab "ALBANIA 2013 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT" (PDF). U.S. Department of State.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-26. Retrieved 2017-03-26.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "The World Factbook: Albania". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

^ "Gallup Global Reports". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

^ "Chronology, 1994-2004 - Cambodian Genocide Program - Yale University". Retrieved 8 August 2015.

^ "Nie: Remembering the deaths of 1.7-million Cambodians". Sptimes.com. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

^ ab Philip Shenon, Phnom Penh Journal; Lord Buddha Returns, With Artists His Soldiers New York Times - January 2, 1992

^ Kiernan 2003, p. 30.

^ Wielander, Gerda (2013). Christian Values in Communist China. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 9781317976042.

^ "China announces "civilizing" atheism drive in Tibet". BBC. 1999. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

^ Campbell, Charlie (25 April 2016). "China's Leader Xi Jinping Reminds Party Members to Be 'Unyielding Marxist Atheists'". Beijing: Time. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

^ Ping Xiong, Freedom of Religion in China Under the Current Legal Framework and Foreign Religious Bodies, 2013 BYU L. Rev. 605 (2014)

Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview/vol2013/iss3/9

^ Arvind Sharma (8 August 2011). Problematizing Religious Freedom. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 201. ISBN 978-90-481-8993-9.

^ Chen, Kenneth (1965). "Chinese Communist Attitudes Towards Buddhism in Chinese History". The China Quarterly. 22: 14. doi:10.1017/S0305741000048682. ISSN 0305-7410.In the journal Hsien-tai Fo-hsueh (Modern Buddhism), September 1959, there appeared a long article entitled "Lun Tsung-chiao Hsin-yang Tzu-yu" ("A Discussion Concerning Freedom of Religious Belief"), by Ya Han-chang, which was originally published in the official Communist ideological journal Hung Ch'i (Red Flag), 1959, No. 14. Appearing as it did in Red Flag it is justifiable to conclude that the views expressed in it represented the accepted Communist attitude toward religion. In this article, Ya wrote that the basic policy of the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Republic of China is to "recognise that everyone has the freedom to believe in a religion, and also that everyone has the freedom not to believe in a religion."

^ The Practice of Chinese Buddhism, 1900–1950 – Page 393

^ Xie, Zhibin, Religious diversity and public religion in China, p.145, Ashgate Publishing 2006

^ Tyler, Christian Wild West China, p. 259, Rutgers Univ. Press 2004

^ "No Religion for Chinese Communist Party Cadres". Deccan Herald. December 2011.

^ abc Temperman, Jeroen (May 30, 2010). State-Religion Relationship and Human Rights Law: Towards a Right to Religiously Neutral Governance. Brill. pp. 141–145.

^ "White Paper—Freedom of Religious Belief in China". Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the United States of America. October 1997. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

^ English translation of the Constitution of the People's Republic of China of 1982 (page visited on 20 February 2015).

^ "Annual Report to Congress on International Religious Freedom". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2007 — China (includes Tibet, Hong Kong, and Macau)". U.S. Department of State. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

^ Madsen, Richard. "Chapter 10. Chinese Christianity: Indigenization and conflict". In Elizabeth J. Perry, Mark Selden. Chinese society: change, conflict and resistance. Routledge. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-415-56073-3.

^ Peter Tze Ming Ng, "Religious Situations in China Today: Secularization Theory Revisited" Paper presented at the Association for the Sociology of Religion Meetings, Chicago, August 14–16, 2002.

^ "China - USCIRF Annual Report 2015" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

^ Katrina Swett (7 Dec 2012). "Remarks by USCIRF Chair Katrina Lantos Swett at Conference on Religious Freedom, Violent Religious Extremism, and Constitutional Reform in Muslim-Majority Countries".The religious freedom situation in Russia is deteriorating and China remains one of the world's most egregious violators of this fundamental right

Missing or empty|url=(help)

^ "China - Country report - Freedom in the World - 2013".

^ Minority Rights Group International, Religious Minorities and China, November 2001, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/469cbf8e0.html [accessed 5 October 2015]

^ United States Department of State, 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom - China, 28 July 2014, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/53d907958e.html [accessed 5 October 2015]

^ United States Department of State, 2013 Report on International Religious Freedom - China: Macau, 28 July 2014, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/53d907945.html [accessed 5 October 2015]

^ Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, China: Freedom of religious practice and belief in Fujian province, 8 October 1999, CHN33002.EX, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6ad442c.html [accessed 5 October 2015]

^ Wee, Sui-Lee. "U.N. official calls China's crackdown on Uighurs "disturbing"".

^ "China lodges protest with U.S. after religious freedom report". Reuters. 4 May 2015.

^ Maldonado, Michelle Gonzalez (1 December 2016). "Religion shapes Cuba despite Castro's influence". The Conversation. Retrieved 5 September 2017.Under Castro's rule, Cuba was for decades a self-declared atheist state where Christians were persecuted and marginalized. ... In 1992 the Cuban Constitution was amended to declare it a secular state. It was no longer an atheist Republic.

^ The State of Religion Atlas. Simon & Schuster.Atheism continues to be the official position of the governments of China, North Korea and Cuba.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ Jay Mallin (1 January 1994). Covering Castro: Rise and Decline of Cuba's Communist Dictator. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-2053-0.

^ Hertzke (2006):43

^ William F. Buckley Jr., Cuba libre? Archived 2011-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, November 21, 2005, National review.

^ "CUBA - Status of Government Respect for Religious Freedom" (PDF). International Religious Freedom Report for 2011. United States Department of State - Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor.

^ "Constitution of Cuba, Article 8: Freedom of Religion and Separation of Church and State". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs.

^ "How Pope John Paul II Paved The Way For The U.S.-Cuba Thaw". The Huffington Post.

^ Nick Miroff (19 September 2015). "Pope Francis arrives in Havana, praising U.S.-Cuba thaw". Washington Post.

^ Rosie Scammell. "Castro thanks Pope Francis for brokering thaw between Cuba and US". the Guardian.

^ "Pope Francis Is Credited With a Crucial Role in U.S.-Cuba Agreement". The New York Times. 18 December 2014.

^ Los Angeles Times (18 December 2014). "Pope Francis' role in Cuba stretches back years". latimes.com.

^ Bandow, Doug (1 February 2016). "The Castros Continue to Shut Churches in Cuba". Newsweek. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

^ Compare: Deseret News National "During the decades of state-sponsored atheism in East Germany, more formally known as the German Democratic Republic, the great emphasis was on avoiding religion."

^ "Ostdeutschland: Wo der Atheist zu Hause ist". Focus. 2012. Retrieved 2017-11-11.52 Prozent der Menschen in Ostdeutschland sind laut einer aktuellen Studie Atheisten. Das ist ein globaler Spitzenwert.

^ "WHY EASTERN GERMANY IS THE MOST GODLESS PLACE ON EARTH". Die Welt. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-08-26. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

^

"East Germany the "most atheistic" of any region". Dialog International. 2012. Retrieved 2009-05-24.

^ DPRK's Socialist Constitution (Full Text)

^ ab "Countries of Particular Concern: Democratic People's Republic of Korea". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

^ "Human Rights in North Korea (DPRK: The Democratic People's Republic of Korea)". Human Rights Watch. 7 July 2004.

^ "The World Factbook". cia.gov.

^ abc "THANK YOU FATHER KIM IL SUNG" (PDF). U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Nov 2005.

^ ab "The Democratic People's Republic of Korea - USCIRF Annual Report" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. 2010.

^ "North Korea Must be Held Accountable for its Abysmal Human Rights Record".

^ "30Giorni - Korea, for a reconciliation between North and South (Interview with Cardinal Nicholas Cheong Jinsuk by Gianni Cardinale)". 30giorni.it. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23.

^ Fox News, November 11, 2013. "North Korea publicly executes 80, some for videos or Bibles, report says"

^ Rough Guides (2015). The Rough Guide to Vietnam. Rough Guides. Religion and beliefs. ISBN 978-0-241-21409-1.After 1975, the Marxist-Leninist government of reunified Vietnam declared the state atheist, ...

^ abc Soberanes Fernandez, Jose Luis, Mexico and the 1981 United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief, pp. 437-438 nn. 7-8, BYU Law Review, June 2002

^ Haas, Ernst B., Nationalism, Liberalism, and Progress: The dismal fate of new nations, Cornell Univ. Press 2000

^ Cronon, E. David "American Catholics and Mexican Anticlericalism, 1933-1936,", pp. 205-208, Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XLV, Sept. 1948

^ abc "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2007-03-03.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE MARTIN-DEL-CAMPOs Part II". myheritage.es. External link in|publisher=(help)

^ ab Joes, Anthony James Resisting Rebellion: The History And Politics of Counterinsurgency p. 70, (2006 University Press of Kentucky)

ISBN 0-8131-9170-X

^ Tuck, Jim THE CRISTERO REBELLION – PART 1 Mexico Connect 1996

^ David A. Shirk (2005). Mexico's New Politics. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-270-7.

^ Denslow, William R. 10,000 Famous Freemasons p. 171 (2004

Kessinger Publishing)

ISBN 1-4179-7578-4

^ Fox, Vicente and Rob Allyn Revolution of Hope p. 17, Viking, 2007

^ Calles, Plutarco Elías The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05 Columbia University Press.

^ The Cristeros: 20th century Mexico's Catholic uprising, from The Angelus, January 2002, Volume XXV, Number 1 Archived 2009-09-03 at the Wayback Machine by Olivier LELIBRE, The Angelus

^ ab Van Hove, Brian Blood Drenched Altars 1996 EWTN

^ abcd Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

^ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 p. 33 (2003

Brassey's)

ISBN 1-57488-452-2

^ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p.393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company)

ISBN 0-393-31066-3

^ "CCPR General Comment 22: 30/07/93 on ICCPR Article 18". Minorityrights.org. Archived from the original on 2015-01-16.

^ International Federation for Human Rights (1 August 2003). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

^ Davis, Derek H. (6 June 2002). "The Evolution of Religious Liberty as a Universal Human Right" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

^ abc "Responding to Religious Freedom and Presidential Leadership: A Historical Approach". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

^ "Mission to Russia - A Rabbi Eulogizes President Reagan".

^ Allen Hertzke (17 Feb 2015). "Responding to Religious Freedom and Presidential Leadership: A Historical Approach". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

References

- Davies, Norman. 1996. Europe: a history. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elsie, Robert. 2000. A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture. C. Hurst & Co.

ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1. - Elsie, Robert. 2001. A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture. New York: NYU Press.

ISBN 0-8147-2214-8. - Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. 2007. Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815. Greenwood Publishing Group.

ISBN 978-0-313-33445-0. - Greeley, Andrew M. 2003. Religion in Europe at the end of the second millennium: a sociological profile. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

- Jacques, Edwin E. 1995. The Albanians: an ethnic history from prehistoric times to the present. McFarland.

ISBN 978-0-89950-932-7. - Marx, Karl. February, 1844. A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher.

- Jonassohn, Kurt and Karin Solveig Bjeornson. 1998. Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations. Transaction Publishers.

ISBN 0-7658-0417-4. - McCann, David R. 1997. Korea briefing: toward reunification, Volume 4 of Korea briefing, Asia Society Briefings Series, Asia Society Country Briefing, Briefings of the Asia Society. M.E. Sharpe.

ISBN 978-1-56324-885-6 - Miner, Steven Merritt. 2003. Stalin's holy war religion, nationalism, and alliance politics, 1941–1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Pospielovsky, Dimitry. 1935. The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia Published 1998. St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 413 pages,

ISBN 0-88141-179-5. - Spielvogel, Jackson. 2005. Western Civilization: Combined Volume. Thomson Wadsworth.

- Tallet, Frank. 1991. Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789. Continuum International Publishing

- Wolak, Arthur J. 2004. Forced out: the fate of Polish Jewry in Communist Poland. Tucson, Ariz: Fenestra Books.