Jim Mooney

| Jim Mooney | |

|---|---|

| Born | (1919-08-13)August 13, 1919 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 30, 2008(2008-03-30) (aged 88) Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Penciller, Inker |

| Pseudonym(s) | Jay Noel |

Notable works | Action Comics (Tommy Tomorrow, Supergirl) Spectacular Spider-Man Star Spangled Comics (Robin) |

James Noel Mooney[1] (August 13, 1919 – March 30, 2008)[2] was an American comics artist best known for his long tenure at DC Comics and as the signature artist of Supergirl, as well as a Marvel Comics inker and Spider-Man artist, both during what comics historians and fans call the Silver Age of comic books. He sometimes inked under the pseudonym Jay Noel.[3]

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Early life and career

1.2 Supergirl and DC

1.3 Spider-Man and Marvel

1.4 Later life and career

2 Bibliography

2.1 DC Comics

2.2 Marvel Comics

3 References

4 External links

Biography

Mooney's cover for the 1938 fanzine Imagination, containing Ray Bradbury's first published story

Early life and career

Jim Mooney was born in New York City and raised in Los Angeles.[4] Friends with pulp-fiction author Henry Kuttner and Californian science-fiction fans such as Forrest J. Ackerman, he drew the cover for the first issue of Imagination, an Ackerman fanzine that included Ray Bradbury's first published story, "Hollerbochen's Dilemma".[5] Kuttner encouraged the teenaged Mooney to submit art to Farnsworth Wright, the editor of the pulp magazine for which Kuttner was writing, Weird Tales. Mooney's first professional sale was an illustration for one of Kuttner's stories in that magazine.[6] During this period, Mooney also met future comic-book editors Mort Weisinger and Julius Schwartz, who had come to the area to meet Kuttner.[7][8]

After attending art school and working as a parking valet and other odd jobs for nightclubs,[9] Mooney went to New York City in 1940 to enter the fledging comic-book field. Following his first assignment, the new feature "The Moth" in Fox Publications' Mystery Men Comics #9-12 (April–July 1940), Mooney worked for the comic-book packager Eisner & Iger, one of the studios that would supply outsourced comics to publishers testing the waters of the new medium. He left voluntarily after two weeks: "I was just absolutely crestfallen when I looked at some of the guys’ work. Lou Fine was working there, Nick Cardy ... and Eisner himself. I was beginning to feel that I was way, way in beyond my depth...." [9]

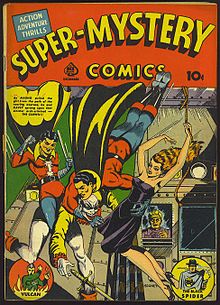

Super Mystery Comics #5 (Dec. 1940): Jim Mooney's first professional cover art

Mooney went on staff at Fiction House for approximately nine months, working on features including "Camilla" and "Suicide Smith" and becoming friends with colleagues George Tuska, Ruben Moreira, and Cardy. He began freelancing for Timely Comics, the 1940s predecessor of Marvel, working on that company's "animation" line of funny animal and movie-cartoon tie-in comics.

As Mooney describes his being hired by editor-in-chief and art director Stan Lee:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

I met Stan the first time when I was looking for work at Timely. . . . I came in, being somewhat young and cocky at the time, and Stan asked me what I did. I said I penciled; he said, 'What else?' I said I inked. He said, 'What else?' I said, 'Color.' 'Do anything else?' I said, 'Yeah, I letter, too.' He said, 'Do you print the damn books, too?' I guess he was about two or three years my junior at that point. I think I was about 21 or 22.[10]

Mooney also wrote and drew a funny-animal feature, "Perky Penguin and Booby Bear", in 1946 and 1947 for Treasure Chest, the Catholic-oriented comic book distributed in parochial schools.[11]

Supergirl and DC

In 1946, Mooney began a 22-year association with the company that would evolve into DC. He began with the series Batman[12] as a ghost artist for credited artist Bob Kane. As Mooney recalled of coming to DC,

[T]he funny animal stuff was no longer in demand, and an awful lot of us were scurrying around looking for work . . . and I heard on the grapevine that they were looking for an artist to do Batman. So I buzzed up there to DC, talked to them and showed them my stuff, and even though they weren't so sure because of my funny-animal background, they gave me a shot at it. I brought the work in, and [editor] Whitney Ellsworth said, 'OK, you're on'. . . . [I]t was ghosting. [Prominent Batman ghost-artist] Dick Sprang [had] taken off and wanted to do something else. So Dick took off for Arizona, and DC was looking for someone to fill in. So, that's where I fit in, and I stayed on Batman for quite a few years. . . .[10]

Writer Bill Finger and Mooney introduced the Catman character in Detective Comics #311 (Jan. 1963).[13] Mooney branched out to the series Superboy, and such features as "Dial H for Hero" in House of Mystery,[14] and Tommy Tomorrow in both Action Comics and World's Finest Comics. He also contributed to Atlas Comics, the 1950s iteration of Marvel, on at least a handful of 1953-54 issues of Lorna the Jungle Queen.[15]

Most notably, Mooney drew the backup feature "Supergirl" in Action Comics from 1959 to 1968.[15] For much of this run on his signature character, Mooney lived in Los Angeles, managing an antiquarian book store on Hollywood Boulevard and sometimes hiring art students to work in the store and ink backgrounds on his pencilled pages.[4] By 1968, he had moved back to New York, where DC, he recalled, was

... getting into the illustrative type of art then, primarily Neal Adams, and they wanted to go in that direction. Towards the end there I picked up on it and I think my later 'Supergirl' was quite illustrative, but not quite what they wanted. I knew the handwriting was on the wall, so I was looking around.... The reason I hadn't worked at Marvel for all those years was because they didn't pay as well as DC. ... I think at that time [it] was $30 [a page] when I was getting closer to $50 at DC".[9]

Spider-Man and Marvel

Jim Mooney drew himself into these three panels from The Spectacular Spider-Man #41 (April 1980).[9]

By now, however, the rates were closer, and Mooney left DC. Marvel editor Stan Lee had him work with The Amazing Spider-Man penciler John Romita. Mooney first worked on Spider-Man by inking The Spectacular Spider-Man magazine's two issues.[16] Mooney would go on to ink a run of Amazing Spider-Man (#65, 67-88; Oct. 1968, Dec. 1968 - Sept. 1970), which he recalled as "finalising it over John’s layouts".[9] Among the new characters introduced during Mooney's run on the title were Randy Robertson as a member of the supporting cast in issue #67 (Dec. 1968)[17] and the Prowler in #78 (Nov. 1969).[18] Mooney also embellished John Buscema's pencils on many issues of The Mighty Thor.

As a penciler, Mooney did several issues of Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man, as well as Spider-Man stories in Marvel Team-Up, and he both penciled and inked issues of writer Steve Gerber's Man-Thing and the entire 10-issue run of Gerber's cult-hit Omega the Unknown,[19][20] among many other titles. Mooney named his collaborations with Gerber as being among his personal favorites.[21] In 2010, Comics Bulletin ranked Gerber and Mooney's run on Omega the Unknown tenth on its list of the "Top 10 1970s Marvels".[22]Carrion debuted in The Spectacular Spider-Man #25 (Dec. 1978) by Bill Mantlo and Mooney.[23] Writer Ralph Macchio and Mooney introduced the Rapier in The Spectacular Spider-Man Annual #2 (1980).[24]

Mooney also worked on Marvel-related coloring books, for the child-oriented Spidey Super Stories, and for a Spider-Man feature in a children's-magazine spin-off of the PBS educational series The Electric Company, which included segments featuring Spider-Man.[15] On the other end of the spectrum, he drew in the late 1960s and early 1970s for Marvel publisher Martin Goodman's bawdy men's-adventure magazine comics feature "The Adventures of Pussycat": "Stan [Lee] wrote the first one I did, and then his brother Larry [Lieber] wrote the ones that came later".[10]

In 1975, Mooney, wanting to move to Florida, negotiated a 10-year contract with Marvel to supply artwork from there. "It was a good deal. The money wasn't too great, but I was paid every couple of weeks, I had insurance, and I had a lot of security that most freelancers never had".[10] That same year, Mooney and his wife, Anne, had a daughter, Nolle.[25]

Later life and career

In Florida, Mooney co-created Adventure Publications' Star Rangers with writer Mark Ellis, and worked on Superboy for DC Comics, Anne Rice's The Mummy for Millennium Publications, and the Creepy miniseries for Harris Comics. When Harris editor Richard Howell left to co-found Claypool Comics in 1993, Mooney produced many stories for the 166-issue run of Elvira, Mistress of the Dark and became the regular inker on writer Peter David's Soulsearchers and Company, over the pencils of Amanda Conner, Neil Vokes, John Heebink, and mostly Dave Cockrum. Mooney also inked four covers of Howell's Deadbeats series. Mooney's other later work included the sole issue of writer Mark Evanier's Flaxen, over Howell pencils; a retro "Lady Supreme" story for Awesome Entertainment; and commissioned pieces.[15] In 1996, Mooney was one of the many creators who contributed to the Superman: The Wedding Album one-shot wherein the title character married Lois Lane.[26]

Mooney's wife Anne died in 2005.[4] Mooney died March 30, 2008, in Florida after an extended illness.[4]

Bibliography

Comics work (pencils or inking) includes:

DC Comics

Action Comics (Tommy Tomorrow) #172-196, 199-251; (Supergirl) #253-342, 344-350, 353-358, 360-373 (1952–69); (Superman) #667 (among other artists) (1991)

Adventure Comics #91, 284 (1944–61); (Legion of Super-Heroes) #328-331, 361 (1965–67)

Adventures of Superboy (based on TV Series) #18-20 (1991)

The Adventures of Superman #480 (among other artists) (1991)

Batman #38, 41, 43-44, 48-49, 53-54, 56, 59-60, 72, 76, 148, 150, (1946–62)

Detective Comics #126, 132, 134, 143, 163, 181, 296, 299, 311, 318 (1947–63)

The Flash, vol. 2, #19 (1988)

House of Mystery #2, 5-6, 10, 20, 23-24, 27, 30, 32-35, 39-40, 46-47, 49, 51, 56, 70, 83, 85, 156-170, 178 (1952–69)

House of Secrets #1, 3-4, 9 (1956–58)

Star-Spangled Comics (Robin) #74, 76-95, 97-130 (1947–52)

Superboy The Comic Book (based on TV series) #1-8 (1990)

Superman #185 (1966)

Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #92 (1966)

Superman: The Wedding Album (among other artists) (1996)

Tales of the Unexpected #10, 17-19, 23-25, 28, 32-33, 35-37, 39-46, 48-49, 53 (1957–60)

World's Finest Comics (Batman) #27, 37, 39-40, 42, 44; (Tommy Tomorrow) #102-120; (Superman and Batman) #121-130, 132-134, 136-140 (1947–64)

Marvel Comics

The Amazing Spider-Man #65, 68-71, 73-81, 86-87 (1968–70)

The Avengers #179-180 (1979)

Battlestar Galactica #14 (1980)

Crypt of Shadows #3, 5, 16 (1973–75)

Ghost Rider #2-9 (1973–74)

The Incredible Hulk vol. 2 #230 (1978)

Invaders #16 (1977)

Journey into Mystery vol. 2 #8 (1973)

Man-Thing #17-22 (1975)

Man-Thing vol. 2 #1-3 (1979–80)

Marvel Comics Presents #16, 73 (1989–91)

Marvel Spotlight #14-17, 27 (1974–76)

Marvel Team-Up #8, 10-11, 24-31, 72 (1973–78)

Ms. Marvel #4-8, 13, 15-18 (1977–78)

Omega the Unknown #1-10 (1976–77)

Solarman #1 (1989)

Son of Satan #1 (1975)

The Spectacular Spider-Man #11, 21, 23, 25-26, 29-34, 36-37, 53, 125 (1977–87)

The Spectacular Spider-Man magazine #1-2 (1968)

Spider-Man, Firestar and Iceman at the Dallas Ballet Nutcracker (1983)

Sub-Mariner #65-66 (1973)

Thundercats #1-6, 19 (1985–88)

Web of Spider-Man #5-6, 10 (1985–86)

References

^ Full name per Treadway, Tyler (April 1, 2008). "Illustrator in Port Salerno was 'one of the nicest guys you'd ever meet'". TC Palm. Stuart, Florida: Scripps Newspaper Group. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ James N. Mooney at the United States Social Security Death Index via FamilySearch.org. Retrieved on March 2, 2013.

^ Evanier, Mark (April 14, 2008). "Why did some artists working for Marvel in the sixties use phony names?". P.O.V. Online. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

^ abcd Evanier, Mark (March 31, 2008). "Jim Mooney, R.I.P." P.O.V. Online. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009.

^ ISFDB publication listing

^ "Jim Mooney". Lambiek Comiclopedia. July 7, 2013. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014.

^ Booker, M. Keith (2010). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. ABC-CLIO. pp. 419–420. ISBN 9780313357466.

^ Boyko, Chris; Mooney, Jim (February 2012). "We Want This To Look Like 'Batman'". Alter Ego. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. 3 (107): 16–17. ISSN 1932-6890.

^ abcde "Jim Mooney". (Interview) Adelaide Comics and Books. March 2004. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

^ abcd "Jim Mooney Over Marvel: From Terrytoons to Omega the Unknown, Jim talks Comics". Comic Book Artist. Raleigh, North Carolina (7). February 2000. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011.

^ "Treasure Chest of Fun and Fact Creators: Mooney, Jim". WRLC Libraries Digital and Special Collection, Catholic University of America, The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

^ Manning, Matthew K.; Dougall, Alastair, ed. (2014). "1940s". Batman: A Visual History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 42. ISBN 978-1465424563.Thanks to the imagination of artists like Dick Sprang and Jim Mooney, Gotham City seemed to be full of giant props that Batman utilized whenever possible to fight his villains.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Forbeck, Matt "1960s" in Dougall, p. 80: "Writer Bill Finger and artist Jim Mooney introduced a new Batman villain destined to return again and again: Catman"

^ McAvennie, Michael; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1960s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.Writer Dave Wood and artist Jim Mooney put young Robby Reed in touch with the mysterious H-Dial.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ abcd Jim Mooney at the Grand Comics Database

^ Manning, Matthew K.; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2012). "1960s". Spider-Man Chronicle Celebrating 50 Years of Web-Slinging. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 43. ISBN 978-0756692360.Drawn by Romita and Jim Mooney, the mammoth 52-page lead story focused on corrupt politician Richard Raleigh's plot to terrorize the city.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 45: "Written by Lee with art by Romita and Mooney...Randy Robertson made his debut. The son of city editor Randy Robertson, he would go on to be the first African American member of Peter Parker's group of friends."

^ Manning "1960s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 49: "In this tale written by [Stan] Lee and drawn by the team of John Buscema and Jim Mooney, window washer Hobie Brown became fed up with his dead-end job and used his inventive mind to craft the identity and weapons of the Prowler."

^ Sanderson, Peter; Gilbert, Laura, ed. (2008). "1970s". Marvel Chronicle A Year by Year History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 175. ISBN 978-0756641238.In March [1976], a new super hero series began called Omega the Unknown, created by writers Steve Gerber and Mary Skrenes and artist Jim Mooney. The title character was an alien humanoid, who rarely spoke and served as protector to an eerily precocious young boy.

CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ Callahan, Timothy (December 2008). "Omega the Unknown". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (31): 41–46.

^ Stroud, Bryan D. (2007). "The Silver Age Sage". WTV-Zone.com. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2013.I loved working with Steve Gerber and Omega to a certain extent, too, but Man-Thing was one of my very favorites.

^ Sacks, Jason (September 6, 2010). "Top 10 1970s Marvels". Comics Bulletin. Archived from the original on August 3, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

^ Manning "1970s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 105: "The ghost of Miles Warren, the villainous Jackal, came to call - in a fashion - in this story written by Bill Mantlo and drawn by Jim Mooney."

^ Manning "1980s" in Gilbert (2012), p. 115: "Although this issue by writer Ralph Macchio and artist Jim Mooney would prove a strong case for the character, he would be destined for a short career in the comic book world."

^ "Bullpen Bulletins": "A Gargantuan Gallery of Garulous [sic] Goings-On Guaranteed to Garner Your Gratitude!", in Marvel Comics cover dated November 1975, including Fantastic Four #164

^ Manning, Matthew K. "1990s" in Dolan, p. 275: " The behind-the-scenes talent on the monumental issue appropriately spanned several generations of the Man of Tomorrow's career. Written by Dan Jurgens, Karl Kesel, David Michelinie, Louise Simonson, and Roger Stern, the one-shot featured the pencils of John Byrne, Gil Kane, Stuart Immonen, Paul Ryan, Jon Bogdanove, Kieron Dwyer, Tom Grummett, Dick Giordano, Jim Mooney, Curt Swan, Nick Cardy, Al Plastino, Barry Kitson, Ron Frenz, and Dan Jurgens."

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jim Mooney. |

Supergirl at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. WebCitation archive 11-25-09

Jim Mooney at Mike's Amazing World of Comics

Jim Mooney at the Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators