War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession (German: Österreichischer Erbfolgekrieg, 1740–1748) involved most of the powers of Europe over the issue of Archduchess Maria Theresa's succession to the Habsburg Monarchy. The war included peripheral events such as King George's War in British America, the War of Jenkins' Ear (which formally began on 23 October 1739), the First Carnatic War in India, the Jacobite rising of 1745 in Scotland, and the First and Second Silesian Wars.

The cause of the war was Maria Theresa' alleged ineligibility to succeed to her father Charles VI's various crowns, because Salic law precluded royal inheritance by a woman. This was to be the key justification for France and Prussia, joined by Bavaria, to challenge Habsburg power. Maria Theresa was supported by Britain, the Dutch Republic, Sardinia and Saxony.

Spain, which had been at war with Britain over colonies and trade since 1739, entered the war on the Continent to re-establish its influence in northern Italy, further reversing Austrian dominance over the Italian peninsula that had been achieved at Spain's expense as a consequence of Spain's war of succession earlier in the 18th century.

The war ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748, by which Maria Theresa was confirmed as Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary, but Prussia retained control of Silesia. The peace was soon to be shattered, however, when Austria's desire to recapture Silesia intertwined with the political upheaval in Europe, culminating in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763).

Contents

1 Background

2 Strategies

3 Silesian Campaign of 1740

4 Allies in Bohemia 1741

5 Campaigns of 1742

6 Campaign of 1743

7 Campaign of 1744

8 Campaign of 1745

9 Italian Campaigns 1741–47

10 The Low Countries; 1745-1748

11 Conclusion of the war

12 General character of the war in Europe

13 North America

14 India

15 Naval operations

15.1 The West Indies

15.2 The Mediterranean

15.3 Northern waters

15.4 The Indian Ocean

16 Strength of armies 1740

17 Related wars

18 Gallery

19 See also

20 References

20.1 Notes

21 Further reading

Background

Europe in the years after the Treaty of Vienna (1738), with the Habsburg Monarchy in gold

The immediate cause of the War of the Austrian Succession was the death in 1740 of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, and the inheritance of Habsburg lands in Austria, Hungary, Croatia, the Netherlands, Bohemia and Italy (often collectively referred to as 'Austria').

When Charles succeeded his elder brother Joseph I in 1711, he was the last male Habsburg heir in the direct line; this meant their lands would be divided on his death as Salic law prevented women inheriting in their own right. A family issue became a European one due to tensions within the Holy Roman Empire, whose monarch was officially chosen by seven prince-electors. The Thirty Years' War of 1618-48 divided the Empire into Protestant and Catholic regions, substantially weakening the bonds holding it together, while by the mid 18th-century states like Bavaria, Prussia and Saxony had increased dramatically in both size and power. The same was also true of the Habsburgs, who now viewed the title of Emperor as being hereditary in practice if not principle (Sigismund the last non-Habsburg Emperor ruled from 1410-1437.) These centrifugal forces led to a war that reshaped the traditional European balance of power; the various legal claims were largely pretexts and seen as such.[1]

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 secured the integrity of the Habsburg inheritance by allowing a female successor, a principle approved by the various Habsburg territories, the Imperial Diet, Spain, Russia, Prussia, Britain and France.[2] However, when his own daughter Maria Theresa was born in 1717, Charles had disinherited his two nieces Maria Josepha and Maria Amalia, married respectively to the rulers of Saxony and Bavaria who now refused to be bound by the decision of the Imperial Diet. In addition, despite publicly agreeing to the Pragmatic Sanction in 1735, France then signed a secret treaty with Bavaria in 1738 promising to back the 'just claims' of Charles Albert of Bavaria.[3]

Charles responded by supporting first the claim of Augustus, Elector of Saxony to the Polish throne in the War of the Polish Succession, then more disastrously Russia in the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739. The losses of men, money and territory in these two conflicts of low strategic value weakened Austria at exactly the wrong time, while Charles also failed to prepare Maria Theresa for her new role, excluding her from any role in government. Many diplomats and statesmen were sceptical Austria could survive the widely anticipated contest that would follow Charles' death, which finally occurred in October 1740.[4]

Strategies

All the participants of the War of the Austrian Succession. Blue: Austria, Great Britain, the United Provinces with allies. Green: Prussia, Spain, France with allies.

For much of the eighteenth century, France approached its wars in the same way: It would either let its colonies defend themselves, or would offer only minimal help (sending them only limited numbers of troops or inexperienced soldiers), anticipating that fights for the colonies would likely be lost anyway.[5] This strategy was, to a degree, forced upon France: geography, coupled with the superiority of the British navy, made it difficult for the French navy to provide significant supplies and support to French colonies.[6] Similarly, several long land borders made an effective domestic army imperative for any ruler of France.[7] Given these military necessities, the French government, unsurprisingly, based its strategy overwhelmingly on the army in Europe: it would keep most of its army on the European continent, hoping that such a force would be victorious closer to home.[7] At the end of the War of Austrian Succession, France gave back its European conquests, while recovering such lost overseas possessions as Louisbourg, largely restoring the status quo ante as far as France was concerned.[8]

The British—by inclination as well as for pragmatic reasons—had tended to avoid large-scale commitments of troops on the Continent.[9] They sought to offset the disadvantage this created in Europe by allying themselves with one or more Continental powers whose interests were antithetical to those of their enemies, particularly France. In the War of the Austrian Succession, the British were allied with Austria; by the time of the Seven Years' War, they were allied with its enemy, Prussia. In marked contrast to France, Britain strove to actively prosecute the war in the colonies once it became involved in the war, taking full advantage of its naval power.[10] The British pursued a dual strategy of naval blockade and bombardment of enemy ports, and also utilized their ability to move troops by sea to the utmost.[11] They would harass enemy shipping and attack enemy outposts, frequently using colonists from nearby British colonies in the effort. This plan worked better in North America than in Europe, but set the stage for the Seven Years' War.

Silesian Campaign of 1740

Maria Theresa, Queen regnant of Hungary and Bohemia and Archduchess of Austria, Holy Roman Empress

Prussia in 1740 was an emerging power, a small but well-organized state whose new king, Frederick II, wanted to unify the disparate and scattered holdings of his crown by gathering intervening lands into a unified, contiguous state. Prince Frederick was 28 years old when he ascended to the throne on 31 May 1740 upon the death of his father, Frederick William I.[12] Although Prussia and Austria had been allies in the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1738), concluded only two years before, the interests of the two countries diverged when the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, died on 20 October 1740. Neither Frederick nor his father had ever been fond of Austria and its various snubs against Prussia (such as offering them the duchies of Julich and Berg in return for an alliance, only to renege later).[13]

Rejecting the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, Frederick opportunistically invaded Silesia on 16 December 1740.[14] In support of his invasion, Frederick used a questionable interpretation of a treaty (1537) between the Hohenzollerns and the Piasts of Brieg as a pretext. What Frederick really feared was that other princes of Europe were preparing to exploit the succession struggle to acquire Habsburg possessions for themselves and/or diminish the power of the Holy Roman Empire. In particular, Frederick feared that Augustus III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, was preparing to seize Silesia for himself to unite Saxony and Poland.[15]

The only recent combat experience of the Prussian Army was their participation in the War of the Polish Succession (Rhine campaign of 1733–1735), in which the Prussians had largely been kept out of combat. Nobody in the Habsburg court trusted the motives of the new rising power of Prussia and, therefore,[citation needed] the Holy Roman Emperor did not call on the Prussians, who were vassals[dubious ] of the Holy Roman Empire, for military support of the Empire. Accordingly, the Prussian Army had an uninspiring reputation and was counted as one of the many minor armies of the Holy Roman Empire. This reputation misrepresented the fact of a standing army of 80,000 soldiers, representing 4% of the 2.2 million population of Prussia.[16] Thus the Prussian Army was disproportionate to the size of the state it protected. By comparison, the Austrian Empire had 16 million citizens but had an army only half its authorised size because of financial restraints. Thus, in defending the vast territory of the Austrian Empire this small army was more of "a sieve"[17] than a shield against foreign invasion.

Lands of the Bohemian Crown until 1742 when most of Silesia was ceded to Prussia

Moreover, the Prussian army was better trained than other armies in Europe and was led by an excellent officer corps. King Frederick William I and "the guiding genius of the Prussian Army",[18]Leopold I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau or "Old Dessauer", had drilled the Prussian Army to a perfection previously unknown in Europe; they were without rival in their discipline, precision and rate of fire. Furthermore, while the Austrians had to wait for conscription to complete the field forces, Prussian regiments took the field at once. With this army it might not have been surprising that Frederick was able to overrun Silesia. However, Frederick sought even more advantages in the war he was planning. Accordingly, he had his Foreign Minister—Heinrich von Podewils—secretly negotiate a treaty with France to put Austria in a two front war. In this way, Prussia could attack the Austrians in the east while France would attack Austria from the west. A treaty with France was signed in April 1739.[19]

In early December, Frederick assembled his army along the Oder river and on 16 December, without a formal declaration of war, the Prussians invaded Silesia. For most of the previous century, Austria's military resources had been concentrated in Hungary and Italy, countering threats from the Ottomans and Spanish respectively, while neglecting less vulnerable areas. As a result, the Austrians had fewer than 3,000 troops available to defend Silesia, and although this was increased to 7,000 shortly before the Prussian attack, they could only hold the fortresses of Glogau, Breslau, and Brieg, abandoning the rest of the province and retreating into Moravia, at which point both sides went into winter quarters.[20] Prussia now controlled most of the single richest province in the Habsburg Empire (Silesian taxes provided 10% of total Imperial income), with a population of over one million, the major commercial centre of Breslau and large mining, weaving and dyeing industries.[21] However, Frederick had hoped to avoid a long war by rapidly capturing all of Silesia, presenting Maria Theresa with a fait accompli, in exchange for which Prussia would guarantee the Habsburgs' other German territories; Austria's retention of its fortresses in Southern Silesia and the failure of Prussian diplomatic efforts to persuade powers like Britain and Russia to agree meant a quick victory could not be achieved.[22]

Allies in Bohemia 1741

Frederick II of Prussia

Early in the year, a new Austrian field army under General Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg relieved Neisse and marched on Brieg, threatening to cut the Prussians off. On 10 April, Frederick's army caught the Austrians on the snow-covered fields near Mollwitz.[23] This was the first time that Frederick had led troops into battle.[24] The victory that Frederick attained at the Battle of Mollwitz was a learning experience for the young King, who departed from the field just before his troops routed the Austrians; both his tactics and his cavalry were rather clumsy, and victory was only obtained due to the discipline of the Prussian infantry and their veteran commander, Field Marshall Kurt von Schwerin.[25]

Frederick obtained an alliance with the French against the Austrians, signing the Treaty of Breslau on 5 June.[26][27] Accordingly, the French began to cross the Rhine on 15 August[27] and joined the Bavarian Elector's forces on the Danube and advanced towards Vienna.[28] The combined forces of the French and the Bavarians captured the Austrian town of Linz on 14 September.[27][28] However, at this point, the objective was suddenly changed, and after many countermarches the anti-Austrian allies advanced, in three widely separated corps, on Prague. A French corps moved via Amberg and Pilsen. The Elector marched on Budweis, and the Saxons (who had now joined the allies against Austria[28]) invaded Bohemia by the Elbe valley. The Austrians could at first offer little resistance, but before long a considerable force intervened at Tábor between the Danube and the allies, and Austrian troops including Neipperg were soon transferred from Silesia back to the west to defend the Austrian capital, Vienna, from the French.

With fewer Austrian troops in Silesia Frederick now had an easier time. The remaining fortresses in Silesia were taken by the Prussians.[26] Before he left Silesia, Austrian General Neipperg had made a curious agreement with Frederick, the so-called Klein–Schnellendorf agreement (9 October 1741). By this agreement, the fortress at Neisse was surrendered after a mock siege, and the Prussians agreed to let the Austrians leave unmolested releasing Neipperg's army for service elsewhere.[29] At the same time the Hungarians, moved to enthusiasm by the personal appeal, in September 1741, of Maria Theresia,[30] had put into the field a levée en masse, or "insurrection," which furnished the regular army with an invaluable force of 60,000 more light troops.[31] A fresh army was collected under Field Marshal Khevenhüller at Vienna, and the Austrians planned an offensive winter campaign against the Franco-Bavarian forces in Bohemia and the small Bavarian army that remained on the Danube to defend the electorate.

Meanwhile, the Saxon-born Maurice de Saxe and a small French force stormed Prague on 26 November 1741. Francis Stephen, husband of Maria Theresa, who commanded the Austrians in Bohemia, moved too slowly to save the fortress. The Elector of Bavaria, who now styled himself Archduke of Austria, was crowned King of Bohemia (9 December 1741) and elected to the imperial throne as Charles VII (24 January 1742), but no active measures were undertaken.

In Bohemia the month of December was occupied in mere skirmishes. On the Danube, Khevenhüller, the best general in the Austrian service, advanced on 27 December, swiftly drove back the allies, shut them up in Linz, and pressed on into Bavaria.[32]Munich itself surrendered to the Austrians on the coronation day of Charles VII.

At the close of this first act of the campaign the French, under the old Marshal de Broglie, maintained a precarious foothold in central Bohemia, menaced by the main army of the Austrians, and Khevenhüller was ranging unopposed in Bavaria. Frederick made a secret truce with Austria and thus, lay inactive in Silesia.

Campaigns of 1742

Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine

Frederick had hoped by the truce to secure Silesia, for which alone he was fighting; although allied with the French, he had no wish to see them become the dominant power in Germany through the destruction of Austria. For their part, the French had aspirations to divide most of the Habsburg territories between themselves, Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony. But with the successes of Khevenhüller and the enthusiastic "insurrection" of Hungary, Maria Theresa's opposition became firmer, and she divulged the provisions of the truce, to compromise Frederick with his allies. The war recommenced. Frederick had not rested idle on his laurels. In the uneventful summer campaign of 1741 he had found time to begin the reorganisation of his cavalry. The training of the Prussian cavalry had been neglected by Frederick's father—King Frederick William I.[33] Probably because he himself was an infantryman to his core, the training of the cavalry had also been overlooked by the "Old Dessauer" who was the true genius behind the Prussian Army.[33] Frederick had been disappointed by the performance of his cavalry at the Battle of Mollwitz.[34] However, as a result of Frederick's training over the summer of 1741 the Prussian cavalry would soon acquit themselves much better in the coming battles of the First Silesian War.

The Bavarian Emperor Charles VII, whose territories were overrun by the Austrians, asked him to create a diversion by invading Moravia. In December 1741, therefore, the Prussian general field marshal Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin crossed the border and captured Olmutz. Glatz also was invested, and the Prussian army was concentrated about Olmutz in January 1742. A combined plan of operations was made by the French, Saxons and Prussians for the rescue of Linz. But Linz soon fell. Broglie on the Vltava, weakened by the departure of the Bavarians to oppose Khevenhüller, and of the Saxons to join forces with Frederick, was in no condition to take the offensive, and large forces under Prince Charles of Lorraine lay in his front from Budweis to Jihlava (Iglau). Frederick's march was made towards Iglau in the first place. Brno was invested about the same time (February), but the direction of the march was changed, and instead of moving against Prince Charles, Frederick pushed on southwards by Znojmo and Mikulov. The extreme outposts of the Prussians appeared before Vienna. But Frederick's advance was a mere foray, and Prince Charles, leaving a screen of troops in front of Broglie, marched to cut off the Prussians from Silesia, while the Hungarian levies poured into Upper Silesia by the Jablunkov Pass. The Saxons, discontented and demoralised, soon marched off to their own country, and Frederick with his Prussians fell back by Svitavy and Litomyšl to Kutná Hora in Bohemia, where he was in touch with Broglie on the one hand and (Glatz having now surrendered) with Silesia on the other. No defence of Olmutz was attempted, and the small Prussian corps remaining in Moravia fell back towards Upper Silesia.

Prince Charles marched past Jihlava and Teutsch (Deutsch) Brod on Kutná Hora in pursuit of Frederick. On 17 May 1742 Frederick turned around and faced the Austrian forces that were pursuing him.[35] He fought the Austrians in what has become known as the Battle of Chotusitz. After a severe struggle Frederick won a major Prussian victory. At Chotusitz, it was Frederick's newly reorganised and trained cavalry that really won the victory[36] and compensated for their previous failings. The cavalry's conduct gave an earnest prospect of its future glory, not only by its charges on the battlefield, but by its vigorous pursuit of the defeated Austrians.

Almost at the same time the Battle of Chotusitz was occurring, French Field Marshal François Broglie fell upon a part of the Austrians left on the Vltava and won a small, but morally and politically important, success in the action of Sahay, near Budweis (24 May 1742). Frederick did not propose another combined movement. Frederick's victory at Chotusitz, along with the victory of Field Marshal Broglie, persuaded Maria Theresa to seek peace even if it meant ceding away Silesia to make good her position elsewhere.[24] Accordingly, a separate peace between Prussia and Austria was signed at Breslau on 11 June 1742, which drew the First Silesian War to a close.[37] However, the larger War of the Austrian Succession continued.

Campaign of 1743

The year 1743 opened disastrously for the forces of the new Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VII. The French and Bavarian armies were not working well together, and Field Marshal Broglie had been placed in command of the allied army in Bavaria.[38] This created tension between Broglie and the Bavarian commanders. Broglie openly quarrelled with the Bavarian field marshal Friedrich Heinrich von Seckendorff. No connected resistance was offered to the converging march of Prince Charles's army along the Danube, Khevenhüller from Salzburg towards southern Bavaria, and Prince Lobkowitz from Bohemia towards the Naab. The Bavarians, under the command of Count Minuzzi, suffered a severe reverse at the town of Simbach near Braunau on 9 May 1743 at the hands of Prince Charles of Lorraine.[39]

George II of Great Britain

Now an Anglo-Allied army commanded by King George II retreated down the Main River to the village of Hanau.[40] This army had been formed on the lower Rhine upon the withdrawal of the French (Westphalian) Army under the command of the Marquis de Maillebois. This allied army became known as the "Pragmatic Army," because it was drawn from a confederation of states that supported the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, which made Maria Theresa sole heir of the Habsburg territories. The Pragmatic Army had been advancing southward up the Main into Neckar country prior to this retreat in the summer of 1743. A French army, under Marshal Noailles, was being collected on the middle Rhine to deal with this new force. Marshal Noailles correctly anticipated that given the problems faced by the Pragmatic Army, George II would take the entire Pragmatic Army back down the Main.[41] Marshal Noailles made plans to lay a trap for the Pragmatic Army and destroy it. However, Marshal Noailles's ally Marshal Broglie was now in full retreat. Strong places of Bavaria were surrendered one after the other to Prince Charles. Marshal Noailles's French army, however, was still intent on finding victory while Marshal de Broglie's Franco-Bavarian army was retreating towards France. In the Dettingen, Noailles attempted a daring maneuver to envelop the British army but his subordinate the Duke de Gramont, without orders, attacked the Pragmatic Army and was defeated with heavy casualties.[42]

King Frederick of Prussia was terrified by the defeat at Dettingen.[43] Frederick saw that he now faced a coalition of potential rivals that included Austria, Britain and Russia.[43] However, Frederick soon realised that the coalition against him was not as strong as it first appeared. Neither Austria nor the British knew how to exploit their victory at Dettingen.[43] Marshal Noailles was driven almost to the Rhine by King George. The French and Bavarian army had been completely outmanoeuvred and was in a position of the greatest danger between Aschaffenburg and Hanau in the defile formed by the Spessart Hills and the river Main. Yet the Pragmatic Army did not quickly follow up the attack. Thus, Marshal Noailles had time to block the outlet and had posts all around. At this point, the allied troops had to force their way through the French and Bavarian lines. Still, because of the heavy losses inflicted on the French, the Battle of Dettingen and the follow up is justly reckoned as a notable victory of Anglo-Austrian-Hanoverian arms.

The coalition against Frederick was suddenly weakened when the St. Petersburg court discovered a plot to overthrow Tsarina Elisabeth and bring back the child Ivan VI as Tsar, with his mother Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna serving as regent for the child.[43] Matters were made much worse for the allies against Frederick when an Austrian envoy Antoniotto Botta Adorno was found to be intimately involved in the plot. Indeed, the plot became known as the "Botta Conspiracy."[44] The Botta-attempted coup redounded badly not only against Austria, but also against the Saxon and British courts.[43] Frederick's initial indifference to a treaty with Russia now changed to enthusiasm in the light of the fallout from the Botta Conspiracy.[45]

Marshal Broglie, worn out by age and exertions, was soon replaced by Marshal Coigny.[46] Both Broglie and Noailles were now on the strict defensive behind the Rhine. Not a single French soldier remained in Germany, and Prince Charles prepared to force the passage of the Rhine river in the Breisgau while George II, King of Britain, moved forward via Mainz to co-operate by drawing upon himself the attention of both the French marshals. The Anglo-allied army took Worms, but after several unsuccessful attempts to cross the Rhine river, Prince Charles went into winter quarters. The king followed his example, drawing his troops to the north, to deal, if necessary, with the army which the French were collecting on the frontier of the Southern Netherlands. Austria, Britain, the Dutch Republic and Sardinia were now allied. Saxony changed sides and the entry of Sweden had offset the loss of Russia to the allies. Thus, Sweden and Russia neutralised each other (Peace of Åbo, August 1743). Frederick was still quiescent. France, Spain and Bavaria actively continued the struggle against Maria Theresa.

While the Battle of Dettingen and Russian Botta plot were capturing all the attention during the summer of 1743, negotiations between the British, the Austrians and Sardinians were proceeding quietly in the city of Worms.[47] The Austrians were desperately afraid that Frederick II would soon be invading the Austrian domains again. Thus, the Austrians sought a separate peace with Sardinia in Italy. Under the terms of the Treaty of Worms, which was signed on 13 September 1743, the Austrian Habsburgs surrendered all territory in Italy located west of the Ticino River and Lake Maggiore to Sardinia.[48] Additionally some lands south of the Po River were also given to Sardinia.[49] In exchange, Sardinia renounced its claim to Milan, guaranteed the Pragmatic Sanction and agreed to provide 40,000 troops for a joint Italian army to fight the Bourbons.

Campaign of 1744

Louis XV of France by Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1748), pastel painting

The Second Silesian War began in 1744. Frederick of Prussia was disquieted by the universal success of the Austrians and their alliance with Sardinia. Accordingly, he secretly concluded another alliance with Louis XV of France.[50] France had posed hitherto as an auxiliary – its officers in Germany had worn the Bavarian cockade – and was officially at war only with Britain. France now declared war directly upon Austria and Sardinia (April 1744).

At this point, the French planned a diversion that they hoped would cause Britain to leave the war. A French army was assembled at Dunkirk to support the cause of Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie) in an invasion of Great Britain. Prince Charles was son of James Francis Edward Stuart, Stuart pretender to the British throne, who was the son of James II the last Catholic and last Stuart king of England. James II had been deposed as the King of England in 1688 in favour of his daughter, Mary, and her husband the Protestant Prince of Orange, William III of the house of Orange-Nassau. A significant element of the British population still hoped for the return of the Stuart family as monarchs. King Louis XIV of France had shown great support for Stuart cause. Indeed, in 1715, France had sponsored an uprising in Scotland, which the pretender James had joined, but it was defeated. Forbidden to return to France by the new king, Louis XV, James sought sanctuary elsewhere. Finally, Pope Clement XI offered James and his family the use of Palazzo Muti and a lifetime annuity of 8,000 Roman scudi. Charles Edward Stuart was born and lived his whole life in the Palazzo Muti.

Charles had much more charisma than his father, and now Louis XV was favourably disposed toward helping him create another uprising in Scotland. Louis XV sent Drummond of Balhaldy as an emissary to the Stuart "court" in Rome.[51] French plans called for Charles to be in Dunkirk, France, to assemble with the fleet on 10 January 1744, yet Balhaldy had only arrived in Rome on 19 December 1743.[52] Thus there was very little time to waste. On 23 December 1743, Charles' father named him "Prince Regent" so that Charles could act in his own name. In the spring of 1744, Prince Charles secretly arrived in France and was about to board the ships that would take him to England. However, on the night before he was to board, a fierce storm blew up (this storm became known as the "Protestant Wind") and wrecked or dispersed the entire fleet.[53] The violent storms had wrecked the crossing attempt, and the planned invasion was abandoned. However, Charles did not give up hope of restoring the Stuart family to the throne of England.

During naval operations that were possible preparations for a coordinated French invasion of England, the largest sea battle of the war occurred, on 22 February 1744.[54]This naval battle took place in the Mediterranean off the coast of Toulon, France. A large British fleet under the command of Admiral Thomas Mathews, with Rear Admiral Richard Lestock second in command, was blockading the French coast. A smaller French and Spanish naval force attacked the British blockade and damaged some of the British ships, forcing the British to withdraw and seek repairs. Thus, the British blockade of the French coast was relieved, and the Spanish fleet apparently controlled the Mediterranean Sea. A Spanish squadron took refuge in the harbour at Toulon. The British fleet watched this squadron carefully from a harbour a short distance to the east. On 21 February 1744, the Spanish ships put to sea with a French fleet. Admiral Mathews took his British fleet and attacked the Spanish fleet from 22 February until 23 February 1744 in what has become known as the Battle of Toulon. However, because of miscommunication and possibly treachery on the part of Rear Admiral Lestock, the smaller Spanish fleet was allowed to escape. With the knowledge that a larger French fleet was sailing to the rescue the British ships broke off combat and retreated to the northeast.

Although technically the Battle of Toulon was regarded as a victory for Britain,[55] in Britain the public feared that the combined French and Spanish ships were making for the Strait of Gibraltar and for a gathering of ships at Brest for a planned invasion of England.[56] As a consequence, bitter recriminations were brought against Admiral Mathews for letting this Spanish-French fleet get away and, subsequently, placing England in danger of invasion. Consequently, both Mathews and Lestock were tried in naval court. Lestock was acquitted (unjustly according to some), while Mathews was found guilty (also regarded as an injustice by some commentators).[54]

Warfare between Deggendorf and Vilshofen, Bavaria

Meanwhile, on the battlefields in northern Europe, Louis XV in person, with 90,000 men, invaded the Austrian Netherlands[57] and took Menin and Ypres in July 1744.[58] His presumed opponent, although shorn of the Russians, still consisted of the same allied army, previously commanded by King George II, and composed of British, Dutch, German (Hanoverian) and Austrian troops.

The French put four armies into the field.[59] On the Rhine, Marshal Coigny had 57,000 troops up against 70,000 allied troops under the command of Prince Charles.[60] A fresh army of over 30,000 soldiers under the Prince de Conti was located between the Meuse and Moselle rivers, which would later assist the Spaniards in Piedmont and Lombardy.[59] This plan was, however, at once dislocated by the advance of Prince Charles, who, assisted by the veteran Marshal Traun, skillfully manoeuvred his allied army over the Rhine near Philippsburg on 1 July 1744 and captured the lines of Weissenburg, and cut off Marshal Coigny and his army from Alsace.[61]

A third French Army composed of 17,000 men under the command of Duke d' Harcourt kept Luxembourg at bay[59] Meanwhile, the fourth French army was the largest army that put to field in the summer of 1744. This was the Army of Flanders, numbering 87,000 men and officially under the command of the king of France, Louis XV, but in actuality he was being militarily advised by Marshal Noailles.[62] As these French forces invaded the Austrian Netherlands, they outnumbered the allied armies by about a four to three ratio.[63] Furthermore, as they marched into the Austrian Netherlands, they met a confused resistance offered by Dutch forces.[64] Consequently, the French Army of Flanders made rapid progress across the Austrian Netherlands.[63] The situation became so desperate for the Dutch that the Dutch government sent an envoy to the king of France to seek peace. This plea for peace was rejected by the French.[63]

However, the situation in the Austrian Netherlands was changed abruptly by the successful crossing of the Rhine on 30 June 1744 by Prince Charles and his 70,000-man allied army.[63] Marshal Coigny, caught far in advance of the other French forces, cut his way back through the enemy at Weissenburg and withdrew towards Strasbourg.[65] Louis XV now abandoned the invasion of the Southern Netherlands, and his army moved down to take a decisive part in the war in Alsace and Lorraine.

Military camp: war of the Austrian succession

Finally, on 12 July 1744, Frederick II of Prussia received confirmation that Prince Charles had taken his army beyond the Rhine and into France.[65] Thus, Frederick knew that Prince Charles would not be able to present any immediate problem to him in the east. Consequently, on 15 August 1744, Frederick II crossed the Austrian frontier into Bohemia, and by late August all 80,000 of his troops were in Bohemia.[66] The attention and resources of Austria had been fully occupied for some time on a renewal of the war in Silesia. However, neither Maria Theresa nor her advisers had expected the Prussians to march as quickly as they did.[31] Accordingly, Frederick's invasion of Bohemia came as a surprise to the Austrian court and Frederick was almost unopposed in Bohemia. One column consisting of 40,000 troops, under Frederick's own command, passed through Saxony; another column of 16,000 men under the command of "Young Dessauer" passed through Lusatia, while a third consisting of 16,000 soldiers under Count Schwerin advanced from Silesia.[67] The destination for all three columns was Prague, and the objective was reached on 2 September. The city was surrounded and besieged. Six days later the Austrian garrison was compelled to surrender.[24] Scarcely had Prague surrendered to Frederick II than he was off marching southwards, leaving 5,000 soldiers under General Baron Gottfried Emanual von Einsiedel to garrison Prague.[68] Three days after the fall of Prague, Frederick seized Tabor, Budweis and Frauenberg.[69]

Maria Theresa once again rose to the emergency: a new "insurrection" took the field in Hungary, and a corps of regulars was assembled to cover Vienna. Meanwhile, Austrian diplomats won over Saxony to the Austrian side.[70] Because of Frederick's successful campaign in Bohemia, Prince Charles sought to withdraw from Alsace and cross the Rhine once again and strike at the Prussians. At this point the French had an excellent chance to strike at Prince Charles while he was in a vulnerable position, crossing the Rhine. However, the French military command was distracted and could not take any action, and Prince Charles was able to cross the Rhine once again unmolested by the French. The French had been unable to act because they were thrown into confusion by King Louis XV suddenly becoming very ill with smallpox at Metz.[67] The King's condition was so severe that many feared for his life. Only Count Seckendorf, commander of the Bavarians, pursued Prince Charles. No move was made by the French, and Frederick thus found himself isolated and exposed to the combined attack of the Austrians and Saxons. Count Traun, summoned from the Rhine, held the king in check in Bohemia with a united force of Austrians and Saxons. The Hungarian irregulars also inflicted numerous minor reverses on the Prussians. Finally Prince Charles arrived with the main army from the west. The campaign resembled that of 1742: the Prussian retreat was closely watched, and the rearguard pressed hard. Prague fell, and Frederick was completely outmanoeuvred by the united forces of Prince Charles and Count Traun.[71] Frederick was forced to retreat to Silesia with heavy losses. However, the Austrians gained no foothold in Silesia itself. On the Rhine, Louis XV, now recovered, had besieged and taken Freiburg,[72] after which the forces left in the north were reinforced and besieged the strong places of Southern Netherlands. There was also a slight war of manoeuvre on the middle Rhine.

Campaign of 1745

Attack of the Prussian Infantry at the Battle of Hohenfriedberg, by Carl Röchling

In 1745 three of the greatest battles of the war occurred: Hohenfriedberg, Kesselsdorf and Fontenoy. The formation of the Quadruple Alliance of Britain, Austria, the Dutch Republic and Saxony was concluded at Warsaw on 8 January 1745 by the Treaty of Warsaw.[73] Twelve days later on 20 January 1745, the death of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VII, submitted the imperial title to a new election.[72] Charles VII's son and heir, Maximilian III of Bavaria, was not even considered a candidate for the Imperial throne. The Bavarian army was again unfortunate. Caught in its scattered winter quarters (action of Amberg, 7 January), it was driven from point to point by a maneuver by the Austrian army under the joint command of Count Batthyány, Baron Bernklau and Count Browne. All Bavarian garrisons fled to the east. The Bavarian Army under the command of Count Törring was divided and paralyzed.[74] The French in the area under Count Ségur marched to save the day. Count Sègur's force out-numbered the Austrian army under Count Batthyany, yet Sègur and the French army were defeated at the Battle of Pfaffenhofen.[74] The young elector Maximilian III had to abandon Munich once more. The Peace of Füssen followed on 22 April 1745, by which Maximilian III secured his hereditary states on condition of supporting the candidature of the Grand-Duke Francis, consort of Maria Theresa. The "imperial" army ceased ipso facto to exist.

The Battle of Fontenoy between the French and the British, by Louis-Nicolas van Blarenberghe

Frederick II of Prussia was again isolated. No help was to be expected from France, whose efforts at the time were centred on the Flanders campaign. Indeed, on 31 March 1745, before Frederick took the field, Louis XV and the Marshal of France Maurice de Saxe, commanding an army of 95,000 men, the largest force in the war, had marched down the Scheldt valley and besieged Tournay.[75] Tournay was defended by a Dutch garrison of 7,000 soldiers.[76] In May 1745, a British army under the command of the Duke of Cumberland attempted to break the French siege and relieve Tournay. Maurice (who had just recently been appointed a Marshal in the French army) had very good intelligence and knew the road that Cumberland was using to attack his forces besieging forces. Thus, Maurice could select the battlefield. Maurice chose to attack the British allied army on a plain on the east side of the Scheldt river about two miles southeast of Tournay near the town of Fontenoy.[77] There the Battle of Fontenoy was fought on 11 May 1745. Fighting began at 5:00 AM with a French artillery barrage of the British-Allied forces, who were still attempting to move into their proper positions for their anticipated attack on Tournay. By noon, Cumberland's troops had ground to a halt and discipline had begun to dissolve. The British-Allied army sought cover in a retreat.[78] It was a victory for the French that captured the attention of Europe because it overturned the mystique of British military superiority, and it pointed out the importance of artillery.[79] On 20 June 1745, after the Battle on Fontenoy, the fortress of Tournay surrendered to the French.[80]

Marshal General Maurice de Saxe

In the summer of 1745, the French once more decided to take up Charles Edward Stuart's claim to the British throne. The goal was to start a revolt in Scotland that would divert British attention away from the war on the mainland in Europe, and may even require Britain to leave the war altogether. On 23 July 1745, Charles landed on the island of Eriskay in the Hebrides, north-west of the mainland of Scotland.[81] On 25 July 1745, Charles set sail again for the mainland. By the end of August 1745, Charles had landed in Scotland and had started issuing calls for troops loyal to the Jacobite cause of placing him on the throne.[82] Already, Charles had collected 1,300 Scots prepared to fight in his Jacobite army.[82] Defence of the Hanovarian rule of King George II in Great Britain fell to General Sir John Cope, a veteran of the Battle of Dettingen. On 31 August 1745, Cope marched north with about 2,000 British government soldiers.[82] Charles reached Perth on 18 September 1745 and Edinburgh surrendered to him on 27 September 1745.[83] When Cope brought his army up to the town of Prestonpans, Scotland on 1 October 1745, he chose a stubble field that he felt was well protected on which to encamp his troops. However, it was not as safe as he thought, and at sunrise the next morning, 2 October 1745, Charles's Scottish troops attacked and defeated the British government army.[84] With the government army defeat at Prestonpans, it appeared that all Scotland belonged to Charles. By November 1745, his army consisted of 5,000 infantry men and 300 cavalry.[85] In mid-November 1745 it crossed the border from Scotland and invaded England.

As the Jacobite army moved south into England, Charles kept assuring his troops that aid and reinforcements from English Jacobites would be arriving at any time. This aide and reinforcements were desperately needed as the Jacobites were badly outnumbered by the three British government armies already in the field.[86] Finally on 6 December 1745, at Derby in the English midlands, Charles was reluctantly persuaded by his senior officers to turn back to Scotland.[87] Upon hearing about the turnabout in Derby, the French gave up on their plans for an invasion of England.[88] The Jacobites felt they could more securely fight the Hanovarians in a defensive battle on Scottish soil rather than fighting the British government army in England. On 17 January 1746, at the Battle of Falkirk Muir, 8,000 Scots, the largest number of troops gathered by the Jacobite cause during the uprising defeated 7,000 of British troops.[89] Ultimately, however, Charles Stuart and his uprising were defeated on 27 April 1746 at the Battle of Culloden.[90]

The manoeuvres of the armies of both sides in the war on the upper Elbe occupied all the summer. Meanwhile, the political questions of the imperial election and of an understanding between Prussia and Britain were pending. The chief efforts of Austria were directed towards the valleys of the Main and of Lahn and Frankfurt, where the French and Austrian armies manoeuvred for a position from which to overawe the electoral body. Austrian Marshal Traun was successful, and, as a result, Francis, the husband/consort of Maria Theresa was elected Holy Roman Emperor on 13 September 1745. Frederick agreed with Britain to recognise the election a few days later, but Maria Theresa would not conform to the Treaty of Breslau of 1741, by which she had been forced to recognise Frederick's annexation of Silesia. Maria Theresa now tried a further appeal to the fortunes of war to get Silesia back. Saxony joined Austria in this last attempt to reconquer Silesia.

In May 1745, The main Prussian army was stationed at Frankenstein. This army consisted of 59,000 soldiers and was fitted with 54 heavy cannons.[91] Frederick learned that a combined Austrian-Saxon army of about 70,000 troops under the command of Prince Charles, was on the march to the northeast towards Landeshut. To meet this threat to Silesia, Frederick II marched north toward Reichenbach. Before he reached Reichenbach, Frederick learned that Prince Charles was crossing the mountains from the west to the east side and that Prince Charles planned to occupy the town of Hohenfriedberg. Accordingly, Frederick encamped his army at Schweidwitz and waited for Prince Charles to come to him. At this site, Frederick laid a trap for the superior Austrian-Saxon forces. Indeed, Frederick was operating on the theory that "to catch a mouse, leave the trap open."[92] At 6:30 AM on 4 June 1745, while the Austrian-Saxon troops were still recovering from their long march, the trap was sprung on them in the Battle of Hohenfriedberg.[93] The Austrian-Saxon forces were no match for Frederick's army and especially his cavalry, and they lost half their artillery and almost a quarter of their men. At 9:00 AM, Prince Charles ordered a full retreat back toward Reichenberg.

A new advance of Prince Charles quickly led to the Battle of Soor on 30 September 1745, fought on ground destined to be famous in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. Frederick commanded an army that at this time numbered only 20,000 soldiers in the vicinity of Soor. He was facing Prince Charles with an army of 41,000 troops.[94] He was at first in a position of great peril, but his army changed front in the face of the advancing enemy, and by its boldness and tenacity won a remarkable victory on 30 September 1745 at Soor.

But the campaign was not ended. An Austrian contingent from the Main joined the Saxons under Field Marshal Rutowsky (1702–1764), and a combined movement was made in the direction of Berlin by Rutowsky from Saxony and Prince Charles from Bohemia. The danger was great. Frederick hurried his forces from Silesia and marched as rapidly as possible on Dresden, in Saxony. Frederick won the actions of Katholisch-Hennersdorf on 24 November 1745 and Görlitz on 25 November. Prince Charles was thereby forced to abandon his plans to attack Silesia and hurry back to defend Saxony. A second Prussian army under the Old Dessauer advanced up the Elbe from Magdeburg to meet Rutowsky. The latter took up a strong position at Kesselsdorf between Meissen and Dresden, but the veteran Leopold attacked him directly and without hesitation on 14 December 1745. The Saxons and their allies were completely routed after a hard struggle in the Battle of Kesselsdorf. Leopold and Frederick then linked up their forces and took Dresden without a struggle. Maria Theresa was, at last, forced to give way. In the Treaty of Dresden signed on 25 December 1745, she recognised Frederick's annexation of Silesia, as first recognised in the Peace of Breslau in 1741. Frederick on the other hand recognised the election of Maria Theresa's husband/consort, Francis I, as the Holy Roman Emperor.

Italian Campaigns 1741–47

Philip V of Spain's family by Louis-Michel van Loo

In central Italy an army of Spaniards and Neapolitans was collected for the purpose of conquering the Milanese. In 1741, the allied army of 40,000 Spaniards and Neapolitans under the command of the Duke of Montmar had advanced towards Modena, the Duke of Modena had allied himself with them, but the vigilant Austrian commander, Count Otto Ferdinand von Traun had out-marched them, captured Modena and forced the Duke to make a separate peace.

The aggressiveness of the Spanish in Italy forced Empress Maria Theresa of Austria and King Charles Emmanuel of Sardinia into negotiations in early 1742.[95] These negotiations were held at Turin. Maria Theresa sent her envoy Count Schulenburg and King Charles Emmanuel sent the Marquis d'Ormea. On 1 February 1742, Schulenburg and Ormea signed the Convention of Turin which resolved (or postponed resolution) many differences and formed an alliance between the two countries.[96] In 1742, field marshal Count Traun held his own with ease against the Spanish and Neapolitans. On 19 August 1742, Naples was forced by the arrival of a British naval squadron in Naples' own harbour, to withdraw her 10,000 troops from the Montemar force to provide for home defence.[97] The Spanish force under Montemar was now too weak to advance in the Po Valley and a second Spanish army was sent to Italy via France. Sardinia had allied herself with Austria in the Convention of Turin and at the same time neither state was at war with France and this led to curious complications, combats being fought in the Isère valley between the troops of Sardinia and of Spain, in which the French took no part. At the end of 1742, the Duke of Montemar was replaced as head of the Spanish forces in Italy by Count Gages.[98]

In 1743, the Spanish on the Panaro had achieved a victory over Traun at Campo Santo on 8 February 1743.[99] However, the next six months were wasted in inaction and Georg Christian, Fürst von Lobkowitz, joining Traun with reinforcements from Germany, drove back the Spanish to Rimini. Observing from Venice, Rousseau hailed the Spanish retreat as "the finest military manoeuvre of the whole century."[100] The Spanish-Savoyan War in the Alps continued without much result, the only incident of note being the first Battle of Casteldelfino (7–10 October 1743), when an initial French offensive was beaten off.

In 1744 the Italian war became serious. Prior to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714) Spain and Austria had been ruled by the same (Habsburg) royal house. Consequently, the foreign policies of Austria and Spain in regards to Italy had a symmetry of interests and these interests were usually opposed to the interests of Bourbon controlled France.[101] However, since the Treaty of Utrecht and the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the childless last Habsburg monarch (Charles II) had been replaced by the Bourbon grandson of the French king Louis XIV Philip of Anjou, who became Philip V in Spain. Now the symmetry of foreign policy interests in regards to Italy existed between Bourbon France and Bourbon Spain with Habsburg Austria usually in opposition.[102] King Charles Emmanuel of Savoy had followed the long-established foreign policy of Savoy of opposing Spanish interference in northern Italy.[56] Now in 1744, Savoy was faced with a grandiose military plan of the combined Spanish and French armies (called the Gallispan army) for conquest of northern Italy.

However, in implementing this plan, the Gallispan generals at the front were hampered by the orders of their respective governments. For example, the commander of the Spanish army in the field, the Prince of Conti, could not get along with, or even reason with, the Marquis de La Mina, the Supreme commander of all Spanish forces.[103] The Prince of Conti felt that the Marquis "deferred blindly to all orders coming from Spain" without any consideration of the realities on the ground.[103] In preparation for the military campaign the Gallispan forces sought to cross the Alps in June 1744 and regroup the army in Dauphiné uniting there with the army on the lower Po.[104]

Charles III of Spain by Anton Raphael Mengs

The support of Genoa allowed a road into central Italy.[103] While the Prince of Conti stayed in the north, Count Gages followed this road to the south. But then the Austrian commander, Prince Lobkowitz took the offensive and drove the Spanish army of the Count de Gages further southward towards the Neapolitan frontier near the small town of Velletri. Velletri just happened to be the birthplace of Caesar Augustus, but now from June through August 1744, Velletri became the scene of extensive military maneuvering between the French-Spanish army under the command of the Count Gages and the Austrian forces under the command of Prince Lobkowitz[105] The King of Naples (the future Charles III of Spain) was increasingly worried about the Austrian army operating so close to his borders and decided to assist the Spaniards. Together a combined army of French, Spanish and Neapolitans surprised the Austrian army on the night of 16–17 June 1744. The Austrians were routed from three important hills around the town of Velletri during the attack.[106] This battle is sometimes called the "Battle of Nemi" after the small town of Nemi located nearby. Because of this surprise attack, the combined army was able to take possession of the town of Velletri. Thus, the surprise attack has also been called the "first Battle of Velletri."

In early August 1744, the King of Naples paid a visit in person to the newly captured town of Velletri.[106] Hearing about the presence of the King, the Austrians developed a plan for a daring raid on Velletri. During the predawn hours of 11 August 1744, about 6,000 Austrians under the direct command of Count Browne staged a surprise raid on the town of Velletri. They were attempting to abduct the King of Naples during his stay in the town. However, after occupying Velletri and searching the entire town, the Austrians found no hint of the King of Naples. The King had become aware of what was happening and had fled through a window of the palace where he was staying and rode off half-dressed on horseback out of the town.[107] This was the second Battle of Velletri. The failure of the raid on Velletri meant that the Austrian march toward Naples was over. The defeated Austrians were ordered north where they could be used in the Piedmont of northern Italy to assist the King of Sardinia against the Prince of Conti. Count de Gages followed the Austrians north with a weak force. Meanwhile, the King of Naples returned home.

The Prince of Conti by Alexis Simon Belle

The war in the Alps and the Apennines had already been keenly contested before the Prince of Conti and the Gallispan army had come down out of the Alps. Villefranche and Montalbán had been stormed by Conti on 20 April 1744. After coming down out of the Alps, Prince Conti began his advance into Piedmont on 5 July 1744.[108] On 19 July 1744, the Gallispan army engaged the Sardinian army in some desperate fighting at Peyre-Longue on 18 July 1744.[109] As a result of the battle, the Gallispan army took control of Casteldelfino in the second Battle of Casteldelfino. Conti then moved on to Delmonte[clarification needed] where on the night of 8–9 August 1744, (a mere 36 hours before the Spanish army in south of Italy fought the second Battle of Velletri, [as noted above]) the Gallispan army took the city of Delmonte from the Sardinians in the Battle of Delmonte.[110] The King of Sardinia was defeated yet again by Conti in a great Battle at Madonna dell'Olmo on 30 September 1744 near Coni (Cuneo).[111] Conti did not, however, succeed in taking the huge fortress at Coni and had to retire into Dauphiné for his winter quarters. Thus, the Gallispan army never did combine with the Spanish army under Count of Gages in the south and now the Austro-Sardinian army lay between them.

The campaign in Italy in 1745 was also no mere war of posts. The Convention of Turin of February 1742 (described above), which established a provisional relationship between Austria and Sardinia had caused some consternation in the Republic of Genoa. However, when this provisional relationship was given a more durable and reliable character in the signing of the Treaty of Worms (1743) signed on 13 September 1743,[112] the government of Genoa became fearful. This fear of diplomatic isolation had caused the Genoese Republic to abandon its neutrality in the war and join the Bourbon cause.[113] Consequently, the Genoese Republic signed a secret treaty with the Bourbon allies of France, Spain and Naples. On 26 June 1745, Genoa declared war on Sardinia.[113]

Empress Maria Theresa, was frustrated with the failure of Lobkowitz to stop the advance of Gage. Accordingly, Lobkowitz was replaced with Count Schulenburg.[114] A change in the command of the Austrians, encouraged the Bourbon allies to strike first in the spring of 1745. Accordingly, Count de Gages moved from Modena towards Lucca, the Gallispan army in the Alps under the new command of Marshal Maillebois (Prince Conti and Marshal Maillebois had exchanged commands over the winter of 1744–1745[115]) advanced through the Italian Riviera to the Tanaro. In the middle of July 1745, the two armies were at last concentrated between the Scrivia and the Tanaro. Together Count de Gage's army and the Gallispan army composed an unusually large number of 80,000 men. A swift march on Piacenza drew the Austrian commander thither and in his absence the allies fell upon and completely defeated the Sardinians at Bassignano on 27 September 1745, a victory which was quickly followed by the capture of Alessandria, Valenza and Casale Monferrato. Jomini calls the concentration of forces which effected the victory "Le plus remarquable de toute la Guerre".

Infante Philip of Spain by Laurent Pécheux

The complicated politics of Italy, however, are reflected in the fact that Count Maillebois was ultimately unable to turn his victory to account. Indeed, early in 1746, Austrian troops, freed by the Austrian peace with Frederick II of Prussia, passed through the Tyrol into Italy. The Gallispan winter quarters at Asti, Italy, were brusquely attacked and a French garrison of 6,000 men at Asti was forced to capitulate.[116] At the same time, Maximilian Ulysses Count Browne with an Austrian corps struck at the allies on the Lower Po, and cut off their communication with the main body of the Gallispan army in Piedmont. A series of minor actions thus completely destroyed the great concentration of Gallispan troops and the Austrians reconquered the duchy of Milan and took possession of much of northern Italy. The allies separated, Maillebois covering Liguria, the Spaniards marching against Browne. The latter was promptly and heavily reinforced and all that the Spaniards could do was to entrench themselves at Piacenza, Philip, the Spanish Infante as supreme commander calling up Maillebois to his aid. The French, skilfully conducted and marching rapidly, joined forces once more, but their situation was critical, for only two marches behind them the army of the King of Sardinia was in pursuit, and before them lay the principal army of the Austrians. The pitched Battle of Piacenza on 16 June 1746 was hard fought but ended in an Austrian victory, with the Spanish army heavily mauled. That the army escaped at all was in the highest degree creditable to Maillebois and to his son and chief of staff. Under their leadership the Gallispan army eluded both the Austrians and the Sardinians and defeated an Austrian corps in the Battle of Rottofreddo on 12 August 1746.[117] Then the Austrian army made good its retreat back to Genoa.

Although the Austrian army was a mere shadow of its former self, when they returned to Genoa, the Austrians were soon in control of northern Italy. The Austrians occupied the Republic of Genoa on 6 September 1746.[118] But they met with no success in their forays towards the Alps. Soon Genoa revolted from the oppressive rule of the victors, rose and drove out the Austrians on 5–11 December 1746. As an Allied invasion of Provence stalled, and the French, now commanded by Charles Louis Auguste Fouquet, Duc de Belle-Isle, took the offensive (1747).[119] Genoa held out against a second Austrian siege.[120] As usual the plan of campaign had been referred to Paris and Madrid. A picked corps of the French army under the Chevalier de Belle-Isle (the younger brother of Marshal Belle-Isle[121]) was ordered to storm the fortified pass of Exilles on 10 July 1747. However, the defending army of the Worms allies (Austria and Savoy) handed the French army a crushing defeat at this battle, which became known as the (Colle dell'Assietta).[122] At this battle, the chevalier, and with him much of the elite of the French nobility, were killed on the barricades.[122] Desultory campaigns continued between the Worms allies and the French until the conclusion of peace at Aix-la-Chapelle.

The Low Countries; 1745-1748

Map of the Low Countries; Bergen op Zoom, upper center

The British and Dutch withdrew from Fontenoy in good order but the French-backed Jacobite rising of August, 1745 forced the British to transfer troops from Flanders to deal with it. By the end of 1745, the French held the strategic towns of Ghent, Oudenarde, Bruges, and Dendermonde, as well as the ports of Ostend and Nieuwpoort, threatening Britain's links to the Low Countries.[123]

During 1746, the French continued their advance into the Austrian Netherlands, taking Antwerp and then clearing Dutch and Austrian forces from the area between Brussels and the Meuse. After defeating the Jacobite Rebellion at Culloden in April, the British launched a diversionary raid on Lorient in an unsuccessful attempt to divert French forces, while the new Austrian commander, Prince Charles of Lorraine, was defeated by Saxe at the Battle of Rocoux in October.[124]

The Dutch Republic itself was now in danger and in April 1747, the French began reducing their Barrier fortresses along the border with the Austrian Netherlands. At Lauffeld on 2 July 1747, Saxe won another victory over a British and Dutch army under the Prince of Orange and Cumberland; the French then besieged Maastricht and Bergen op Zoom, which fell in September.[124]

These events lent greater urgency to ongoing peace talks at the Congress of Breda, which took place to the sound of French artillery firing on Maastricht. Following their 1746 alliance with Austria, an army of 30,000 Russians marched from Livonia to the Rhine, but arrived too late to be of use. Maastricht surrendered on 7 May and on 18 October 1748, the war ended with the signing of the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle.[125]

Conclusion of the war

Europe in the years after the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle in 1748

The War of Austrian Succession concluded with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748). Maria Theresa and Austria survived nearly status quo ante bellum, sacrificing only the territory of Silesia, which Austria conceded to Prussia, and a few minor territorial losses to Spain in northern Italy. While Austria was far from crippled, the loss of Silesia was, in great measure, a humiliating defeat for Austria's leadership of the German states within the Holy Roman Empire. By contrast, Prussian gains nearly doubled the size of its economy, territory and population, while Frederick II's success as a commander soon earned him the epithet "Frederick the Great". This marked the beginning of the German dualism between Prussia and Austria, which would ultimately fuel German nationalism and the drive to unify Germany as a single entity.[citation needed]

Despite his victories, Louis XV of France, who wanted to appear as an arbiter and statesman and not as a conqueror, gave all of his conquests back to his defeated enemies with honour, arguing that he was "King of France, not a merchant".[126] This decision, largely misunderstood by his generals and by the French people, made the king unpopular at home. The French obtained so little of what they had fought for that they adopted the expressions Bête comme la paix ("Stupid as the peace") and Travailler pour le roi de Prusse ("To work for the king of Prussia", i.e. working for nothing). France definitely succeeded in humiliating Maria Theresa and her kingdom. But because of this France had bolstered Prussia's power, which would continue to grow, to France's later detriment. Twice during the war, Prussia had made peace with Austria without informing France, leading Louis XV to consider Frederick II of Prussia (whom he already greatly disliked) an untrustworthy ally. Despite the long history of conflict between the Houses of Habsburg and Bourbon, he began to make overtures of alliance to Austria instead.

Spain, in one way or another, managed to achieve some of her war aims, which mostly centred on an effort to reinstate Spanish influence in the Italian peninsula.

Britain managed to get out of the war with a favorable settlement and on its own terms, which angered the Austrians; Britain's power was increasing and its interests becoming even more complex. Realizing that Austria was no longer the sole hegemon of Central Europe, Britain decided to align itself with Prussia in order to protect Hanover from future French attack. This alliance however ended up destabilizing the continent, as the other great powers braced themselves with a counter grand alliance for an upcoming war that proved to be even grander in scale.

General character of the war in Europe

The triumph of Prussia was in a great measure due to its fuller application of principles of tactics and discipline universally recognised though less universally enforced. The other powers reorganised their forces after the war, not so much on the Prussian model as on the basis of a stricter application of known general principles. Prussia, moreover, was far ahead of all the other continental powers in administration, and over Austria, in particular, its advantage in this matter was almost decisive. Added to this was the personal ascendancy of Frederick as both monarch and commander, as opposed to generals who were responsible for their men to their individual sovereigns.[citation needed]

The war, like other conflicts of the time, featured an extraordinary disparity between the end and the means. The political schemes to be executed by the French and other armies were as grandiose as any of modern times. Their execution, under the conditions of time and space, invariably fell short of expectations, and the history of the war proves, as that of the Seven Years' War was to prove, that the small standing army of the 18th century could conquer by degrees, but could not deliver a decisive blow. Frederick alone, with a definite end and proportionate means to achieve it, succeeded. Less was to be expected when the armies were composed of allied contingents, sent to the war each for a different object. The allied national armies of 1813 (at the Battle of Leipzig) co-operated loyally, for they had much at stake and worked for a common object. Those of 1741 represented the divergent private interests of the several dynasties, and achieved nothing.[citation needed]

- Further Reading: "To the Queen of Hungary" is a poem by Voltaire which describes the character of the war from a largely French perspective.

North America

The war was also conducted in North America and India. In North America the conflict was known in the British colonies as King George's War, and did not begin until after formal war declarations of France and Britain reached the colonies in May 1744. The frontiers between New France and the British colonies of New England, New York, and Nova Scotia were the site of frequent small scale raids, primarily by French colonial troops and their Indian allies against British targets, although several attempts were made by British colonists to organise expeditions against New France. The most significant incident was the capture of the French Fortress Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island (Île Royale) by an expedition (29 April – 16 June 1745) of colonial militia organised by Massachusetts Governor William Shirley, commanded by William Pepperrell of Maine (then part of Massachusetts), and assisted by a Royal Navy fleet. A French expedition to recover Louisbourg in 1746 failed due to bad weather, disease, and the death of its commander. Louisbourg was returned to France in exchange for Madras, generating much anger among the British colonists, who felt they had eliminated a nest of privateers with its capture.

India

Flag of the East India Company (founded in 1600)

British Admiral Edward Boscawen besieged Pondicherry in the later months of 1748.

The war marked the beginning of great power in England and the powerful struggle between Britain and France in India and of European military ascendancy and political intervention in the subcontinent. Major hostilities began with the arrival of a naval squadron under Mahé de la Bourdonnais, carrying troops from France. In September 1746 Bourdonnais landed his troops near Madras and laid siege to the port. Although it was the main British settlement in the Carnatic, Madras was weakly fortified and had only a small garrison, reflecting the thoroughly commercial nature of the European presence in India hitherto. On 10 September, only six days after the arrival of the French force, Madras surrendered. The terms of the surrender agreed by Bourdonnais provided for the settlement to be ransomed back for a cash payment by the British East India Company. However, this concession was opposed by Dupleix, the governor general of the Indian possessions of the Compagnie des Indes. When Bourdonnais was forced to leave India in October after the devastation of his squadron by a cyclone Dupleix reneged on the agreement. The Nawab of the Carnatic Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan intervened in support of the British and advanced to retake Madras, but despite vast superiority in numbers his army was easily and bloodily crushed by the French, in the first demonstration of the gap in quality that had opened up between European and Indian armies.

The French now turned to the remaining British settlement in the Carnatic, Fort St. David at Cuddalore, which was dangerously close to the main French settlement of Pondichéry. The first French force sent against Cuddalore was surprised and defeated nearby by the forces of the Nawab and the British garrison in December 1746. Early in 1747 a second expedition laid siege to Fort St David but withdrew on the arrival of a British naval squadron in March. A final attempt in June 1748 avoided the fort and attacked the weakly fortified town of Cuddalore itself, but was routed by the British garrison.

With the arrival of a naval squadron under Admiral Boscawen, carrying troops and artillery, the British went on the offensive, laying siege to Pondichéry. They enjoyed a considerable superiority in numbers over the defenders, but the settlement had been heavily fortified by Dupleix and after two months the siege was abandoned.

The peace settlement brought the return of Madras to the British company, exchanged for Louisbourg in Canada. However, the conflict between the two companies continued by proxy during the interval before the outbreak of the Seven Years' War, with British and French forces fighting on behalf of rival claimants to the thrones of Hyderabad and the Carnatic.

The naval operations of this war were entangled with the War of Jenkins' Ear, which broke out in 1739 in consequence of the long disputes between Britain and Spain over their conflicting claims in America. The war was remarkable for the prominence of privateering on both sides. It was carried on by the Spaniards in the West Indies with great success, and actively at home. The French were no less active in all seas. Mahé de la Bourdonnais's attack on Madras partook largely of the nature of a privateering venture. The British retaliated with vigour. The total number of captures by French and Spanish corsairs was in all probability larger than the list of British – as the French wit Voltaire drolly put it upon hearing his government's boast, namely, that more British merchants were taken because there were many more British merchant ships to take; but partly also because the British government had not yet begun to enforce the use of convoy so strictly as it did in later times.

The West Indies

Vice-Admiral Edward Vernon

War on Spain was declared by Great Britain on 23 October 1739, which has become known as the War of Jenkins' Ear. A plan was laid for combined operations against the Spanish colonies from east and west. One force, military and naval, was to assault them from the West Indies under Admiral Edward Vernon. Another, to be commanded by Commodore George Anson, afterwards Lord Anson, was to round Cape Horn and to fall upon the Pacific coast of Latin America. Delays, bad preparations, dockyard corruption, and the squabbles of the naval and military officers concerned caused the failure of a hopeful scheme. On 21 November 1739, Admiral Vernon did, however, succeed in capturing the ill-defended Spanish harbour of Porto Bello in present-day Panama. When Vernon had been joined by Sir Chaloner Ogle with massive naval reinforcements and a strong body of troops, an attack was made on Cartagena in what is now Colombia (9 March – 24 April 1741). The delay had given the Spanish under Sebastián de Eslava and Blas de Lezo time to prepare. After two months of skilful defence by the Spanish, the British attack finally succumbed to a massive outbreak of disease and withdrew having suffered a dreadful loss of lives and ships.

The war in the West Indies, after two other unsuccessful attacks had been made on Spanish territory, died down and did not revive until 1748. The expedition under Anson sailed late, was very ill-provided, and less strong than had been intended. It consisted of six ships and left Britain on 18 September 1740. Anson returned alone with his flagship the Centurion on 15 June 1744. The other vessels had either failed to round the Horn or had been lost. But Anson had harried the coast of Chile and Peru and had captured a Spanish galleon of immense value near the Philippines. His cruise was a great feat of resolution and endurance.

After the failure of the British invasions and a Spanish counter invasion of Georgia in 1742, belligerent naval actions in the Caribbean were left to the privateers of both sides. Fearing great financial and economic losses should a treasure fleet be captured, the Spanish reduced the risk by increasing the number of convoys, thereby reducing their value. They also increased the number of ports they visited and reduced the predictability of their voyages.

In 1744 300 British militia, slaves and regulars with two privateers from Saint Kitts invaded the French half of neighbouring Saint Martin, holding it until the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. In late May 1745 two French royal frigates of 36 and 30 guns respectively under Commodore La Touché, plus three privateers in retaliation sailed from Martinique to invade and capture Anguilla but were repelled with heavy loss.

The last year of the war saw two significant actions in the Caribbean. A second British assault on Santiago de Cuba which also ended in failure and a naval action which arose from an accidental encounter between two convoys. The action unfolded in a confused way with each side at once anxious to cover its own trade and to intercept that of the other. Capture was rendered particularly desirable for the British by the fact that the Spanish homeward-bound fleet would be laden with bullion from the American mines. The advantage lay with the British when one Spanish warship ran aground and another was captured but the British commander failed to capitalise and the Spanish fleet took shelter in Havana.

The Mediterranean

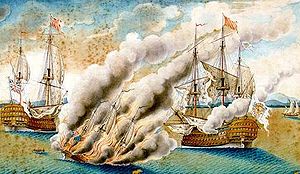

The Franco-Spanish fleet commanded by Don Juan José Navarro drove off the British fleet under Thomas Mathews near Toulon in 1744.

While Anson was pursuing his voyage round the world, Spain was mainly intent on the Italian policy of the King. A squadron was fitted out at Cádiz to convey troops to Italy. It was watched by the British admiral Nicholas Haddock. When the blockading squadron was forced off by want of provisions, the Spanish admiral Don Juan José Navarro put to sea. He was followed, but when the British force came in sight of him Navarro had been joined by a French squadron under Claude-Elisée de La Bruyère de Court (December 1741). The French admiral announced[how? clarification needed] that he would support the Spaniards if they were attacked and Haddock retired. France and Great Britain were not yet openly at war, but both were engaged in the struggle in Germany—Great Britain as the ally of the Queen of Hungary, Maria Theresa; France as the supporter of the Bavarian claimant of the empire. Navarro and de Court went on to Toulon, where they remained until February 1744. A British fleet watched them, under the command of Admiral Richard Lestock, until Sir Thomas Mathews was sent out as commander-in-chief and as Minister to the Court of Turin.

Sporadic manifestations of hostility between the French and British took place in different seas, but avowed war did not begin until the French government issued its declaration of 30 March, to which Great Britain replied on 31 March. This formality had been preceded by French preparations for the invasion of England, and by the Battle of Toulon between the British and a Franco-Spanish fleet. On 11 February, a most confused battle was fought, in which the van and centre of the British fleet was engaged with the Spanish rear and centre of the allies. Lestock, who was on the worst possible terms with his superior, took no part in the action. Mathews fought with spirit but in a disorderly way, breaking the formation of his fleet, and showing no power of direction, while Navarro's smaller fleet retained cohesion and fought off the energetic but confused attacks of its larger enemy until the arrival of the French fleet forced the heavily damaged British fleet to withdraw. The Spanish fleet then sailed to Italy where it delivered a fresh army and supplies that had a decisive impact upon the war. The mismanagement of the British fleet in the battle, by arousing deep anger among the people, led to a drastic reform of the British navy.

Northern waters