LGBT rights in Iran

LGBT rights in Iran | |

|---|---|

Iran | |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Illegal: Islamic law is applied. |

Penalty: | Imprisonment, lashing, execution (see below) |

Gender identity/expression | Sex reassignment surgery, which is required to change legal gender, is legalized and is partially paid for by the government. |

| Discrimination protections | None |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Iran face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. While people can legally change their assigned gender, sexual activity between members of the same sex is illegal.

LGBT rights in Iran have come in conflict with the penal code since the 1930s.[1] In post-revolutionary Iran, any type of sexual activity outside a heterosexual marriage is forbidden. Same-sex sexual activities are punishable by imprisonment,[2]corporal punishment, or execution. Gay men have faced stricter enforcement actions under the law than lesbians.

Transgender identity is recognized through a sex reassignment surgery. Sex reassignment surgeries are partially financially supported by the state. Some homosexual individuals in Iran have been pressured to undergo sex reassignment surgery in order to avoid legal and social persecution.[3] Iran carries out more sex reassignment surgeries than any other country in the world after Thailand.

Contents

1 LGBT history in Iran

2 Legal status

2.1 Male same-sex sexual activity

2.2 Female same-sex sexual activity

2.3 Laws regarding transsexuality

3 Application of laws

3.1 Capital punishment

3.1.1 Rape

3.1.2 Sodomy

3.2 Arrests

3.3 Gender identity

4 Family and relationships

5 Censorship

6 Exiled political parties and groups

7 LGBT rights movement

8 HIV/AIDS

9 Asylum cases

10 Views of the government on homosexuality

11 Human rights reports

11.1 United States Department of State

11.1.1 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices of 2017

12 Summary table

13 See also

14 Notes

15 References

16 External links

LGBT history in Iran

Around 250 BC, during the Parthian Empire, the Zoroastrian text Vendidad was written. It contains provisions that are part of sexual code promoting procreative sexuality that is interpreted to prohibit same-sex intercourse as sinful. Ancient commentary on this passage suggests that those engaging in sodomy could be killed without permission from a high priest. However, a strong homosexual tradition in Iran is attested to by Greek historians from the 5th century onward, and so the prohibition apparently had little effect on Iranian attitudes or sexual behavior outside the ranks of devout Zoroastrians in rural eastern Iran.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

There is a significant amount of literature in Persian that contain explicit same-sex illustrations.[10] A few Persian love poems and texts from prominent medieval Persian poet Saadi Shirazi's Bustan and Gulistan have also been interpreted as homoerotic poems.[11]

Under the rule of Mohammad Reza Shah, the last monarch of the Pahlavi dynasty, homosexuality was tolerated, even to the point of allowing news coverage of a same-sex wedding. Janet Afary has argued that the 1979 Revolution was partly motivated by moral outrage against the Shah's government, and in particular against a mock same-sex wedding between two young men with ties to the court. She says that this explains the virulence of the anti-homosexual oppression in Iran.[12] After the 1979 Revolution, thousands of people were executed in public, including homosexuals.[13][14]

A Safavid Persian miniature from 1627, depicting Abbas I of Iran with a page. Louvre, Paris.

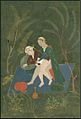

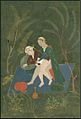

A Safavid Persian miniature from 1660, depicting two men engaged in anal sex. Kinsey Institution, Bloomington.

A Safavid Persian miniature from 1720, depicting two men engaged in anal sex. Kinsey Institution, Bloomington.

A depiction of a youth conversing with suitors from Jami's Haft Awrang, in the story A Father Advises his Son About Love. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Men and youths depicted on a Safavid ceramic panel from Chehel Sotoun, Isfahan. Louvre, Paris.

Legal status

Since the 1979 Revolution, the legal code has been based on Islamic law. All sexual activities that occur outside a traditional, heterosexual marriage (i.e., sodomy or adultery) are illegal. Same-sex sexual activities that occur between consenting adults are criminalized and carry a maximum punishment of death—though not generally implemented. Forced same-sex sexual activities (i.e., rape) often result in execution. The death penalty is legal for those above 18, and if a murder was committed, legal at the age of 15. Approved by the Parliament on July 30, 1991, and finally ratified by the Guardian Council on November 28, 1991, articles 108 through 140 distinctly deal with same-sex sexual activities and their punishments in detail.[citation needed]

Male same-sex sexual activity

According to Articles 108 to 113, sodomy (lavāt) can in certain circumstances be a crime for which both partners can be punished by death. If the participants are adults, of sound mind and consenting, the method of execution is for the judge to decide. If one person is non-consenting (i.e., rape), the punishment would only apply to the rapist. A non-adult who engages in consensual sodomy is subject to a punishment of 74 lashes. Articles 114 to 119 assert that sodomy is proved either if a person confesses four times to having committed sodomy or by the testimony of four righteous men. Testimony of women alone or together with a man does not prove sodomy. According to Articles 125 and 126, if sodomy, or any lesser crime referred to above, is proved by confession and the person concerned repents, the judge may request that he be pardoned. If a person who has committed the lesser crimes referred to above repents before the giving of testimony by the witnesses, the punishment is quashed. The judge may punish the person for lesser crimes at his discretion.

Female same-sex sexual activity

According to Articles 127, 129, and 130, the punishment for female same-sex sexual activity (mosāheqe) involving persons who are mature, of sound mind and consenting, is 50 lashes. If the act is repeated three times and punishment is enforced each time, the death sentence will apply on the fourth occasion. Article 128 asserts that the ways of proving female same-sex sexual activity in court are the same as for sodomy. Article 130 says that both Muslims and non-Muslims are subject to the punishment. According to Articles 132 and 133, the rules for the quashing of sentences, or for pardoning, are the same as for the lesser male homosexual offenses. According to Article 134, women who "stand naked under one cover without necessity" and are not relatives may receive a punishment of 50 lashes.

Laws regarding transsexuality

As Article 20 in Clause 14 states, a person who has done a sex reassignment surgery can legally change their name and gender on the birth certification upon the order of court.

Those who are in favor of legitimately being able to reassign one's sex surgically utilize article 215 of Iran's civil code, stating that the acts of every person should be subject to rational benefit, meaning gender reassignment surgery would be in the best interest of whomever is appealing for governmental support. Caveats, however, include the need to have medical approval from a doctor that supports a dissonance between assigned gender and their true gender.

Although legally recognized by the current Supreme Leader in Iran, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Grand Ayatollah Yousef Madani Tabrizi addresses gender reassignment surgery as "unlawful" and "not permissible by Sharia (Islamic law)".[clarification needed] Reasons for his contestation include the altering of God's creation and disfiguration of vital organs as being unlawful.[15][unreliable source?]

Application of laws

At the discretion of the Iranian court, fines, prison sentences, and corporal punishment are usually carried out rather than the death penalty, unless the crime was a rape.[citation needed]

The charges of same-sex sexual activity have in a few occasions been used in political crimes. Other charges had been paired with the sodomy crime, such as rape or acts against the state, and convictions are obtained in grossly flawed trials. On March 14, 1994, famous dissident writer Ali Akbar Saidi Sirjani was charged with offenses ranging from drug dealing to espionage to homosexual activity. He died in prison under disputed circumstances.[16]

Capital punishment

A protester of the killing of homosexual people in Iran. Washington, DC. July 19, 2006.

Some human rights activists and opponents of the government in Iran claim between 4,000 and 6,000 gay men and lesbians have been executed in Iran for crimes related to their sexual orientation since 1979.[17][18] According to The Boroumand Foundation,[19] there are records of at least 107 executions with charges related to homosexuality between 1979 and 1990.[20] According to Amnesty International, at least 5 people convicted of "homosexual tendencies", three men and two women, were executed in January 1990, as a result of the government's policy of calling for the execution of those who "practice homosexuality".[21]

In a November 2007 meeting with his British counterpart, Iranian member of parliament Mohsen Yahyavi admitted that the government in Iran believes in the death penalty for homosexuality. According to Yahyavi, gays deserve to be tortured, executed, or both.[22]

Rape

Rape (tajāvoz, zenā be onf) is punishable by death by hanging. Ten to fifteen percent of executions in Iran are for rape. The rape victim may settle the case by accepting compensation (jirat) in exchange for withdrawing the charges or forgiving the rapist.[citation needed] This is similar to diyya, but equal to a woman's dowry. A woman can also receive diyya for injuries sustained. Normally, the rapist still faces tazir penalties, such as 100 lashes and jail time for immoral acts, and often faces further penalties for other crimes committed alongside the rape, such as kidnapping, assault, and disruption of public order.

On July 19, 2005, two teenagers from the province of Khorasan who were convicted by the court of having raped a 13-year-old boy were publicly hanged. The case attracted international media attention, and the British LGBT group OutRage! alleged that the teenagers were executed for consensual homosexual acts and not rape.[23] It was disputed in the media as to whether the executions of the two teenagers, or that of three other men who were executed in 2011 in the province of Khuzestan, were punishment for other crimes or carried out specifically because of their same-sex sexual activity.[24]Human Rights Watch, while condemning the executions of the juveniles, stated "there is no evidence that this was a consensual act", and observed that "the bulk of evidence suggests that the youths were tried on allegations of raping a 13-year-old, with the suggestion that they were tried for consensual homosexual conduct seemingly based almost entirely on mistranslations and on cursory news reporting magnified by the Western press".[25] It also stated that it was "deeply disturbed by the apparent indifference of many people to the alleged rape of a 13-year old".[25]

Another controversial execution was that of Makwan Moloudzadeh on December 6, 2007. He was convicted of lavāt be onf (sodomy rape) and executed for raping three teenage boys when he was 13, even though all witnesses had retracted their accusations and Moloudzadeh withdrew a confession. As a 13-year-old, he was ineligible for the death penalty under the law in Iran.[26][27] Despite international outcry and a nullification of the death sentence by Chief Justice Ayatollah Seyed Mahmoud Hashemi Shahrud, Moloudzadeh was hanged without his family or his attorney being informed until after the fact.[28][29] The execution provoked international outcry since it violated two international treaties signed by the government in Iran that outlaw capital punishment for crimes committed by minors—the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[30]

Sodomy

Few consenting participants of sodomy (lavāt) are sentenced to death, but prior to 2012, both partners could receive the death penalty. On March 15, 2005, the daily newspaper Etemad reported that the Tehran Criminal Court sentenced two men to death following the discovery of a video showing them engaged in sexual acts. Another two men were allegedly hanged publicly in the northern town of Gorgan for sodomy in November 2005.[31] In July 2006, two youths in north-eastern Iran were hanged for "sex crimes", probably consensual homosexual acts.[2] On November 16, 2006, the State-run news agency reported the public execution of a man convicted of sodomy in the western city of Kermanshah.[32]

Arrests

On January 23, 2008, Hamzeh Chavi, 18, and Loghman Hamzehpour, 19, were arrested in Sardasht, West Azerbaijan for homosexual activity. An on-line petition for their release began to circulate around the internet.[33] They apparently confessed to the authorities that they were in a relationship and in love, prompting a court to charge them with mohārebe ("waging war against God") and lavāt (sodomy).

There were two reported crackdowns in Isfahan, Iran's third-largest city. On May 10, 2007, Isfahan police arrested 87 people at a birthday party, including 80 suspected gay men, beating and detaining them through the weekend.[34] All but 17 of the men were released. Those who remained in custody were believed to have been wearing women's clothing.[35] Photos of the beaten men were released by the Toronto-based Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees.[36] According to Human Rights Watch, in February 2008, the police in Isfahan raided a party in a private home and arrested 30 men, who were held indefinitely without a lawyer on suspicion of homosexual activity.[37]

In April 2017, 30 men were arrested in a raid in Isfahan Province, "charged with sodomy, drinking alcohol and using psychedelic drugs".[38]

Gender identity

In Islam, the term mukhannathun ("effeminate ones") is used to describe gender-variant people, usually transgender people who are transitioning from male to female. Neither this term nor the equivalent for "eunuch" occurs in the Quran, but the term does appear in the Hadith, the sayings of Muhammad, which have a secondary status to the central text. Moreover, within Islam, there is a tradition on the elaboration and refinement of extended religious doctrines through scholarship.[citation needed]

While Iran has outlawed homosexual activity, Iranian Shia thinkers such as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini have allowed for transsexuals to reassign their sex so that they can enter heterosexual relationships. This position has been confirmed by the current Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and is also supported by many other Iranian clerics. The state will pay a portion of the cost for a gender reassignment operation.[citation needed]

Since the mid-1980s, the Iranian government has legalized the practice of sex reassignment surgery (under medical approval) and the modification of pertinent legal documents to reflect the reassigned gender. In 1983, Khomeini passed a fatwa allowing gender reassignment operations as a cure for "diagnosed transsexuals", allowing for the basis of this practice becoming legal.[39][40] This religious decree was first issued for Maryam Khatoon Molkara, who has since become the leader of an Iranian transsexual organization. Hojatoleslam Kariminia, a mid-level Islamic cleric in Iran, is another advocate for transsexual rights, having called publicly for greater respect for the rights of Iranian transsexuals. However, transsexuality is still a taboo topic within Iranian society, and no laws exist to protect post-operative transsexuals from discrimination.

Some homosexual individuals in Iran have been pressured to undergo sex reassignment surgery in order to avoid legal and social persecution.[3][3]Tanaz Eshaghian's 2008 documentary Be Like Others highlighted this.[3] The documentary explores issues of gender and sexual identity while following the personal stories of some of the patients at a gender reassignment clinic in Tehran. The film was featured at the Sundance Film Festival and the Berlin International Film Festival, winning three awards.[41] Sarah Farizan's novel If You Could Be Mine explores the relationship between two young girls, Sahar and Nisrin, who live in Iran through gender identity and the possibility of undergoing gender reassignment surgery. In order for the two to be in an open relationship, Sahar considers surgery to work within the confines of law which permits relationships after transitioning due to the relationship being between a male and female.

Family and relationships

Same-sex marriage and civil union are not legally recognized in Iran. Traditional Iranian families often exercise strong influence in who, and when, their children marry and even what profession they chose.[42] Few LGBT Iranians come out to family for the fear of being rejected. No legislation exists to address discrimination or bias motivated violence on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity.[citation needed]

Traditional Iranian families tend to prohibit their children from dating, as it is not a part of Iranian culture, although this has become somewhat more tolerated, among liberals.[42] In 2004, an independent film was released, directed by Maryam Keshavarz, that examined the changing mores of Iranian youth when it comes to sex and dating.[43]

Gay Iranian couples are often afraid to be seen together

[44] in public, and report that LGBT people were widely stereotyped as being sex-obsessed child molesters, rapists, and diseased ridden.[45] A popular Iranian derogatory slur against is that of a, "evakhahar", typically a very effeminate gay man who seeks casual sex in public.[46]

Censorship

In 2002, a book entitled Witness Play by Cyrus Shamisa was banned from shelves (despite being initially approved) because it said that certain notable Persian writers were homosexuals or bisexuals.[47]

In 2004, the government in Iran loaned an Iranian collection of artwork that was locked away since the 1979 Revolution by the Tate Britain gallery for six months. The artwork included explicit homoerotic artwork by Francis Bacon and the government in Iran stated that upon its return, it would also be put on display in Iran.[48]

In 2005, the Iranian Reformist paper Shargh was shut down by the government after it interviewed an Iranian author, living in Canada. While the interview never mentioned the sexual orientation of Saghi Ghahreman, it did quote her as stating that, "sexual boundaries must be flexible... The immoral is imposed by culture on the body".[49] The conservative paper Kayhan attacked the interview and the paper, "Shargh has interviewed this homosexual while aware of her sick sexual identity, dissident views and porno-personality."[49] To avoid being permanently shut down, the paper issued a public apology stating it was unaware of the author's "personal traits" and promised to "avoid such people and movements."[49]

Exiled political parties and groups

The government in Iran does not allow a political party or organization to endorse LGBT rights. Vague support for LGBT rights in Iran has fallen to a handful of exiled political organizations.

The Green Party of Iran has an English translation of its website that states, "Every Iranian citizen is equal by law, regardless of gender, age, race, nationality, religion, marital status, sexual orientation, or political beliefs" and calls for a "separation of state and religion".[50]

The Worker Communist Party of Iran homepage has an English translation of its manifesto that supports the right of "All adults, women or men" to be "completely free in deciding over their sexual relationships with other adults. Voluntary relationship of adults with each other is their private affair and no person or authority has the right to scrutinize it, interfere with it or make it public".[51]

The leftist Worker's Way, the liberal Glorious Frontiers Party, and the center-right Constitutionalist Party of Iran have all expressed support for the separation of religion and the state, which might promote LGBT rights.

LGBT rights movement

Boat 15 Iran, 2017 Amsterdam Gay Pride.

In 1972, scholar Saviz Shafai gave a public lecture on homosexuality at the Shiraz University and in 1976 would research sexual orientation and gender issues at Syracuse University. In the 1990s, he joined the first human rights group for LGBT Iranians, HOMAN, and continued his work until he died of cancer in 2000.[52]

In 2001, an online Iranian LGBT rights organization called "Rainbow" was founded by Arsham Parsi, a well-known Iranian gay activist, followed by a clandestine organization named the "Persian Gay and Lesbian Organization". As of 2008, this group has been renamed as the "Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees" (IRQR). While the founder of this group had to flee Iran and continue his work as an exile, there is an underground LGBT rights movement in Iran.[53]

Ali Mafi, an openly gay Iranian-born comedian started his career in 2016. In all his shows, Ali mentions his status as an Iranian citizen and his commitment to being proud of who he is regardless. Ali currently resides in San Francisco, California, which hosts a prominent gay community.

In 2007, the Canadian CBC TV produced a documentary that interviewed several LGBT Iranians who talked about their struggles.

During protests against the outcome of the Iranian election in July 2009, it was reported that several openly gay Iranians joined crowds of protesters in the United Kingdom and were welcomed with mostly positive attitudes towards LGBT rights.[54]

In 2010, a group of LGBT activists inside Iran declared a day to be Iran Pride Day. The day is on the fourth Friday of July and is and celebrated annually in secret.[55]

As of 2012, OutRight Action International develops an online resource for LGBTIQ Iranians in Persian.

JoopeA organized the Iran in Amsterdam Pride as the Iran Boat (Dutch: Iraanse Boot) in the Amsterdam Gay Pride festival in 2017 and 2018. The Iran Boat won the Best of Pride Amsterdam 2018 (Dutch: Publieksprijs) award.[56][57]

HIV/AIDS

Despite the deeply conservative character of the government in Iran, its efforts to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS have been quite progressive.[58] The first official reports of HIV/AIDS in Iran were reported in 1987, and a government commission was formed, albeit it was not until the 1990s that a comprehensive policy began to arise.[58]

In 1997, Dr. Arash Alaei and his brother, Kamiar, were given permission to open up a small office for HIV/AIDS research among prisoners and with a few years, despite public protests, they helped open the first general HIV/AIDS clinics. A booklet was approved, with explanation of condoms, and distributed to high school students. By the late 1990s, a comprehensive educational campaign existed. Several clinics opened up to offer free testing and counseling. Government funds were allocated to distribute condoms to prostitutes, clean needles and drug rehabilitation to addicts and programs aired on television advocating the use of condoms.[58] While there are shortages, medication is given to all Iranian citizens free of charge.

The Alaei brothers were joined in their educational campaign by Dr. Minoo Mohraz, who was also an early proponent of greater HIV/AIDS education, who chairs a research center in Tehran. Along with government funding, UNICEF has funded several Iranian volunteer based groups that seek to promote greater education about the pandemic and to combat the prejudice that often follows Iranians who have it.[59][60]

In June 2008, the Alaei brothers were detained, without charge, by the government in Iran, after attending an international conference on HIV/AIDS.[61] The government has since accused the two doctors of attending the conference as part of a larger plotting to overthrow the government.[62]

In 2007, the government in Iran stated that 18,320 Iranians had been infected with HIV, bringing the official number of deaths to 2,800, although critics claimed that the actual number might've been much higher.[63] Officially, drug addiction is the most common way that Iranians become infected.

While educational programs exist for prostitutes and drug addicts, no educational campaign for LGBT has been allowed to exist. In talking about the situation Kaveh Khoshnood stated, "Some people would be able to talk about their own drug addiction or their family members, but they find it incredibly difficult to talk about homosexuality in any way". "If you're not acknowledging its existence, you're certainly not going to be developing any programs [for gays]".[64]

Asylum cases

Some middle-class Iranians have received an education in a Western nation. There is a small population of gay Iranian immigrants who live in Western nations. However, most attempts by gay Iranians to seek asylum in a foreign country based on the government's anti-gay policies have failed, considering its policies are mild compared to U.S. allies such as Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

In 2001, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights rejected a plea from an Iranian man who escaped from an Iranian prison after being convicted and sentenced to death for the crime of homosexual activity.[65] Part of the problem with this case was that the man had entered the country illegally and was later convicted of killing his boyfriend, after he discovered that he had been unfaithful.

In 2005, the Japanese government rejected an asylum plea from another Iranian gay man. That same year, the Swedish government also rejected a similar claim by an Iranian gay man's appeal. The Netherlands is also going through a review of its asylum policies in regard to Iranians claiming to be victims of the anti-gay policies in Iran.

In 2006, the Netherlands stopped deporting gay men back to Iran temporarily. In March 2006, Dutch Immigration Minister Rita Verdonk said that it was now clear "that there is no question of executions or death sentences based solely on the fact that a defendant is gay", adding that homosexuality was never the primary charge against people. However, in October 2006, after pressure from both within and outside the Netherlands, Verdonk changed her position and announced that Iranian LGBTs would not be deported.[66]

The United Kingdom came under fire for its continued deporting, especially due to news reports documenting gay Iranians who committed suicide when faced with deportation. Some cases have provoked lengthy campaigning on behalf of potential deportees, sometimes resulting in gay Iranians being granted asylum, as in the cases of Kiana Firouz[67] and Mehdi Kazemi.[68]

Views of the government on homosexuality

Iran's state media have shown their hatred toward homosexuality on many occasions, and no press or other media outlet in Iran is allowed to support LGBT rights.[citation needed] In particular, Mashregh News, a news website "close to the security and intelligence organizations", has described homosexuals in an article as "individuals who have become mentally troubled in natural human tendencies, have lost their balance, and require psychological support and treatment".[69]

One outlet, the website of Press TV, an English-language TV news channel owned by the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, formerly had a written policy that banned homophobic comments.[70]

In 2007, former president of Iran Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, speaking to Columbia University, stated that "In Iran, we don't have homosexuals", though a spokesperson later stated that his comments were misunderstood.[71]

Human rights reports

United States Department of State

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices of 2017

Children

The review noted many concerns, including discrimination against girls; children with disabilities; unregistered, refugee, and migrant children; and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) minors.[72]

Acts of Violence, Discrimination, and Other Abuses Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

The law criminalizes consensual same-sex sexual activity, which is punishable by death, flogging, or a lesser punishment. The law does not distinguish between consensual and nonconsensual same sex intercourse, and NGOs reported this lack of clarity led to both the victim and the perpetrator being held criminally liable under the law in cases of assault. The law does not prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

Security forces harassed, arrested, and detained individuals they suspected of being gay or transgender. In some cases security forces raided houses and monitored internet sites for information on LGBTI persons. Those accused of “sodomy” often faced summary trials, and evidentiary standards were not always met. Punishment for same-sex sexual activity between men was more severe than between women.

According to international and local media reports, on April 13 at least 30 men suspected of homosexual conduct were arrested by IRGC agents at a private party in Isfahan Province. The agents reportedly fired weapons and used electric Tasers during the raid. According to the Canadian-based nonprofit organization Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees, those arrested were taken to Dastgerd Prison in Isfahan, where they were led to the prison yard and told they would be executed. The Iranian LGBTI activist group 6Rang noted that, following similar raids, those arrested and similarly charged were subjected to forced “anal” or “sodomy” tests and other degrading treatment and sexual insults.

The government censored all materials related to LGBTI issues. Authorities particularly blocked websites or content within sites that discussed LGBTI issues, including the censorship of Wikipedia pages defining LGBTI and other related topics. There were active, unregistered LGBTI NGOs in the country. Hate crime laws or other criminal justice mechanisms did not exist to aid in the prosecution of bias-motivated crimes.

The law requires all male citizens over age 18 to serve in the military but exempts gay and transgender women, who are classified as having mental disorders. New military identity cards listed the subsection of the law dictating the exemption.

According to 6Rang this practice identified the men as gay or transgender and put them at risk of physical abuse and discrimination.

The government provided transgender persons financial assistance in the form of grants of up to 45 million rials $1,240 and loans up to 55 million rials $1,500 to undergo gender reassignment surgery. Additionally, the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labor, and Social Welfare required health insurers to cover the cost of such surgery. Individuals who undergo gender reassignment surgery may petition a court for new identity documents with corrected gender data, which the government reportedly provided efficiently and transparently. NGOs reported that authorities pressured LGBTI persons to undergo gender reassignment surgery.[72]

Summary table

| Right | Yes/No | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | Imprisonment, corporal punishment, execution. | |

| Equal age of consent | ||

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | ||

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | ||

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | ||

| Same-sex marriages | ||

| Recognition of same-sex couples | ||

| Step-child adoption by same-sex couples | ||

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | ||

| Gays and lesbians allowed to serve openly in the military | Based on Article 33 of the army's medical exemption regulations, "moral and sexual deviancy, such as transsexuality" is considered to be grounds for a medical exemption from the military service, which is mandatory for eligible male individuals over 18.[73] According to Human Rights Watch, in order to "prove" their sexual orientation or gender identity, men seeking a military exemption on that basis would be required to undergo "numerous" "humiliating" physical and psychological tests, which may be costly, and they may also encounter administrative barriers, such as "few doctors" to perform such tests and doctors that refuse to perform them without parental accompaniment.[73] | |

| Right to change legal gender | Applied through a sex reassignment surgery. | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | ||

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | ||

MSM allowed to donate blood |

See also

- Gender Identity Organization of Iran

Be Like Others, a documentary film about transsexuality in Iran- Transgender rights in Iran

- Human rights in Iran

Notes

^ "Interview with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad". Larry King Live. CNN. 2008-09-23. Retrieved 2014-06-29..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Ann Penketh (March 6, 2008). "Brutal land where homosexuality is punishable by death". The Independent. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

^ abc "Iran's gay plan". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

^ Ervad Behramshah Hormusji Bharda (1990). "The Importance of Vendidad in the Zarathushti Religion". tenets.zoroastrianism.com. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

^ Ervad Marzban Hathiram. "Significance and Philosophy of the Vendidad" (PDF). frashogard.com. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

^ "Ranghaya, Sixteenth Vendidad Nation & Western Aryan Lands". heritageinstitute.com. Heritage Institute. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

^ Jones, Lesley-Ann (2011-10-13). Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography: The Definitive Biography. Hachette UK, 2011. p. 28. ISBN 9781444733709. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

^ Darmesteter, James (1898). Sacred Books of the East (American ed.). Vd 8:32. Retrieved January 3, 2015.(...) Ahura Mazda answered: 'The man that lies with mankind as man lies with womankind, or as woman lies with mankind, is the man that is a Daeva; this one is the man that is a worshipper of the Daevas, that is a male paramour of the Daevas, that is a female paramour of the Daevas, that is a wife to the Daeva; this is the man that is as bad as a Daeva, that is in his whole being a Daeva; this is the man that is a Daeva before he dies, and becomes one of the unseen Daevas after death: so is he, whether he has lain with mankind as mankind, or as womankind. The guilty may be killed by any one, without an order from the Dastur (see § 74 n.), and by this execution an ordinary capital crime may be redeemed. (...)

^ Neill, James (2011). The Origins and Role of Same-Sex Relations in Human Societies. McFarland. p. 92. ISBN 9780786452477.

^ ">> literature >> Middle Eastern Literature: Persian". glbtq. Archived from the original on October 4, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Liukkonen, Petri. "Sa'di". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012.

^ "Iranian Sources Question Rape Charges in Teen Executions". Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved May 19, 2012.

^ "Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, 89, the Unwavering Iranian Spiritual Leader". The New York Times. 1989.

^ "An Interview With KHOMEINI". The New York Times. October 7, 1979.

^ Saeidzadeh, Zara (2014). "The Legality of Sex Change Surgery and Construction of Transsexual Identity in Contemporary Iran". Lund University. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016.

^ "Leading Dissident Writer in Iran Dies After 8 Months in Detention". The New York Times. November 28, 1994. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

^ "Iran: Uk Grants Asylum To Victim Of Tehran Persecution Of Gays, Citing Publicity". The Daily Telegraph. London. February 4, 2011.

^ Encarnación, Omar G. (February 13, 2017). "Trump and Gay Rights: The Future of the Global Movement". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved February 14, 2017.Amnesty International reports that some 5,000 gays and lesbians have been executed in Iran since the 1979 Iranian Revolution, including two gay men executed in 2014, both hanged for engaging in consensual homosexual relations.

– via Foreign Affairs (subscription required)

^ "The Boroumand Foundation". Abfiran.org. December 10, 1998. Archived from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Search the Iran Human Rights Memorial, Omid – Boroumand Foundation for Human Rights in Iran". Abfiran.org. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Un-named person (male) – Promoting Human Rights in Iran". Abfiran.org. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Gays should be hanged, says Iranian minister; The Times, November 13, 2007; Retrieved on April 1, 2008(subscription required)

^ [1][dead link]

^ "Iran executes three men on homosexuality charges". The Guardian. September 7, 2011.

^ ab "Response to Peter Tatchell's 'Open Letter'", distributed on e-mail by Scott Long. Human Rights Watch. July 18, 2006.

^ "Iranian hanged after verdict stay". BBC News. December 6, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

^ Amnesty International Press Release after the execution of Moloudzadeh. Archived March 11, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

^ Statement of the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ Iran seen hanging man for raping boys, Frederick Dahl, Reuters via the International Herald Tribune, December 6, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2008. Archived December 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ Statement of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, December 7, 2007. Archived March 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

^ "Iran: Two More Executions for Homosexual Conduct". Human Rights Watch. November 21, 2005. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

^ IGLHRC Condemns Iran's Continued Use of Sodomy Laws To Justify Executions and Arbitrary Arrests, IGLHRC, July 18, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2008.[dead link]

^ "Petition for the Lives of Two Iranian Gay Guys: Hamzeh and Loghman, at Risk of Death Sentence". indymedia.be. January 28, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

^ "More Than Eighty 'Gay' Men Arrested at Birthday Party in Isfahan". The Advocate. ukgaynews.org.uk. May 14, 2007. Archived from the original on April 14, 2011.

^ Amnesty International press release, May 17, 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2008. Archived February 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

^ Photos of Isfahan men beaten by police, Iranian Queer Organization. Retrieved September 20, 2008.[not in citation given]

^ "Iran: Private Homes Raided for 'Immorality'". Human Rights Watch. March 28, 2008. Archived from the original on November 13, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Weinthal, Benjamin (April 20, 2017). "SHOTS FIRED AS IRAN ARRESTS OVER 30 GAY MEN IN VIOLENT RAID". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

^ Barford, Vanessa (25 February 2008). "Iran's 'diagnosed transsexuals'". BBC. Archived from the original on February 29, 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

^ "Film – Iran's gay plan". CBC News. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on February 22, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Blizek, William L.; Ruby Ramji (April 2008). "Report from Sundance 2008: Religion in Independent Film". Journal of Religion and Film. 12 (1). Archived from the original on February 10, 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

^ ab "Culture of Iran". February 1, 2003.

^ "The Color of Love (Range Eshgh)". Tiburon International Film Festival. March 26, 2007. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Fozoole Mahaleh. آیا هم جنس گرایی، یک بیماری است و یا یک نوع علاقه و دلبستگی میان دو انسان؟ [Sexism, a disease or a type of interest between two people?] (in Persian). FozooleMahaleh.com. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

^ Arsham Parsi (September 7, 2007). "Interview with Iranian Gay Couple". Gay Republic Daily. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ [2] Archived March 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ "Book on homosexuality ordered off shelves". Iran News.

^ https://web.archive.org/web/20090408045630/http://globalgayz.com/iran-news97-04.html. Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-02. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ abc https://web.archive.org/web/20090314002508/http://www.globalgayz.com/iran-news07-02.html. Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-02. Missing or empty|title=(help)

^ "Green Party of Iran Platform". Green Party of Iran. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Worker-communist Party of Iran". Wpiran.org. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Gay Iran News & Reports 1997-2004". Archived from the original on April 8, 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

^ "Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Nell Frizzell (June 19, 2009). "President of Iran admits gays do exist in his country as 700-strong crowd protests in London". Pink News. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

^ Morgan, Michaela (27 July 2017). "LGBT+ Iranians are set to celebrate Pride in secret with 'Rainbow Friday'". SBS.

^ "Prijswinnaars Canal Parade bekend, Iraanse boot wint publieksprijs" (in Dutch). AT5. 5 August 2018.De Iraanse boot heeft de publieksprijs van de Canal Parade gewonnen.

^ Bolwijn, Marjon (5 August 2018). "'Iedereen mag zijn wie hij wil zijn' tijdens de Canal Parade" (in Dutch). de Volkskrant.Hun (Iraaniers) opvallend ingetogen blauw gekleurde boot won de publieksprijs.

^ abc "Iran's AIDS-prevention Program Among World's Most Progressive". Commondreams.org. April 14, 2006. Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Celebrity Football Match Launches Global Campaign in Iran". UNICEF. December 5, 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Kevin Sites in the Hot Zone – Video – Yahoo! News". Hotzone.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Joe Amon (July 20, 2008). "Iran: Release Detained HIV/AIDS Experts". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ "Freed!". Physicians for Human Rights.

[not in citation given]

^ "Iran Reports 30 Percent Rise in HIV Infection on 2007". The Body. Agence France Presse. October 20, 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ Post a Comment (December 31, 2004). "Stories – Iran tackles AIDS head-on — International Reporting Project". International Reporting Project. Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

^ For The Record 2003 – United Nations – Treaty Bodies Database – Document – Jurisprudence – Netherlands Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

^ Netherlands: Asylum Rights Granted to Lesbian and Gay Iranians; October 26, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2007. Archived November 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

^ "Refugees. EveryOne Group: Kiana Firouz, has been granted permission to remain in the UK". Everyonegroup.com. June 18, 2010. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

^ Canning, Paul (2008-04-03). "Mehdi Kazemi: On his way back : Dutch "We have confidence in a good outcome"". LGBT Asylum News. Retrieved 2013-11-02.

^ آشنایی با ابعاد آشکار و پنهان ترویج همجنس بازی در جهان ["Understanding the Evident and Hidden Dimensions of the Promotion of Homophilia in the World"]. Mashregh News. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

^ "Comment Policy". presstv.ir. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

^ "Ahmadinejad Says Comments About Gays Were Misunderstood". Fox News. October 30, 2007. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

^ ab "IRAN 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT" (PDF).

^ ab "Iran: Military service, including recruitment age, length of service, reasons for exemption, the possibility of performing a replacement service and the treatment of people who refuse military service by authorities; whether there are sanctions against conscientious objectors" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. March 28, 2014.

References

^ Safra Project Country Information Report Iran. 2004 report, and consider UNHCR report underestimate the pressure. Mentions gender diversity on pp, 15.- The Secret World of Iran's Gay and Lesbian community

External links

"LGBT Activists Gather For Rare Show Of Public Pride In Iran (PHOTOS)". HuffPost. December 6, 2017.

"Homosexuality". Encyclopædia Iranica. April 20, 2012.