Dresden

| Dresden | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise: Dresden at night, Dresden Frauenkirche, Schloss Pillnitz, Dresden Castle and Zwinger | |||

| |||

Dresden | |||

| Coordinates: 51°2′N 13°44′E / 51.033°N 13.733°E / 51.033; 13.733Coordinates: 51°2′N 13°44′E / 51.033°N 13.733°E / 51.033; 13.733 | |||

| Country | Germany | ||

| State | Saxony | ||

| District | Urban district | ||

| Government | |||

| • Lord Mayor | Dirk Hilbert (FDP) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 328.8 km2 (127.0 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 113 m (371 ft) | ||

| Population (2017-12-31)[1] | |||

| • City | 551,072 | ||

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,300/sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 780,561 | ||

| • Metro | 1,143,197 | ||

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | ||

| Website | www.dresden.de | ||

Historic city centre with main sights

Dresden (German pronunciation: [ˈdʁeːsdn̩] (![]() listen); Upper and Lower Sorbian: Drježdźany; Czech: Drážďany; Polish: Drezno) is the capital city[2] and, after Leipzig, the second-largest city[3] of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the border with the Czech Republic.

listen); Upper and Lower Sorbian: Drježdźany; Czech: Drážďany; Polish: Drezno) is the capital city[2] and, after Leipzig, the second-largest city[3] of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the border with the Czech Republic.

Dresden has a long history as the capital and royal residence for the Electors and Kings of Saxony, who for centuries furnished the city with cultural and artistic splendor, and was once by personal union the family seat of Polish monarchs. The city was known as the Jewel Box, because of its baroque and rococo city centre. The controversial American and British bombing of Dresden in World War II towards the end of the war killed approximately 100,000 people, many of whom were civilians, and destroyed the entire city centre. After the war restoration work has helped to reconstruct parts of the historic inner city, including the Katholische Hofkirche, the Zwinger and the famous Semper Oper.

Since German reunification in 1990 Dresden is again a cultural, educational and political centre of Germany and Europe. The Dresden University of Technology is one of the 10 largest universities in Germany and part of the German Universities Excellence Initiative. The economy of Dresden and its agglomeration is one of the most dynamic in Germany and ranks first in Saxony.[4] It is dominated by high-tech branches, often called “Silicon Saxony”. The city is also one of the most visited in Germany with 4.3 million overnight stays per year.[5][6] The royal buildings are among the most impressive buildings in Europe. Main sights are also the nearby National Park of Saxon Switzerland, the Ore Mountains and the countryside around Elbe Valley and Moritzburg Castle. The most prominent building in the city of Dresden is the Frauenkirche. Built in the 18th century, the church was destroyed during World War II. The remaining ruins were left for 50 years as a war memorial, before being rebuilt between 1994 and 2005.

According to the Hamburgische Weltwirtschaftsinstitut (HWWI) and Berenberg Bank in 2017, Dresden has the fourth best prospects for the future of all cities in Germany.[7][8]

Contents

1 History

1.1 Early history

1.2 Early-modern age

1.2.1 Military history

1.3 Second World War

1.4 Post-war

1.5 Post-reunification

2 Geography

2.1 Location

2.2 Nature

2.3 Climate

2.4 Flood protection

2.5 City structuring

2.6 Demographics

3 Governance

3.1 Municipality and city council

3.2 Local affairs

4 Twin towns – sister cities

5 Culture and architecture

5.1 Entertainment

5.2 Museums, presentations and collections

5.3 Architecture

5.3.1 Royal household

5.3.2 Sacred buildings

5.3.3 Contemporary architecture

5.3.4 Other buildings

5.3.5 Dresden-Hellerau—Germany's first garden city

5.3.6 Living quarters

5.4 Cinemas and cinematics

5.5 Sport

5.6 Main sights

6 Infrastructure

6.1 Transport

6.2 Public utilities

7 Economy

7.1 Enterprises

8 Media

9 Education and science

9.1 Universities

9.2 Research institutes

9.3 Higher secondary education

9.4 Sons and daughters of the town

10 Honourary Citizens

11 Notes

12 References

13 Bibliography

14 External links

History

The Fürstenzug—the Saxon sovereigns depicted in Meissen porcelain

Although Dresden is a relatively recent city of Germanic origin followed by settlement of Slavic people,[9] the area had been settled in the Neolithic era by Linear Pottery culture tribes ca. 7500 BC.[10] Dresden's founding and early growth is associated with the eastward expansion of Germanic peoples,[9] mining in the nearby Ore Mountains, and the establishment of the Margraviate of Meissen. Its name etymologically derives from Old Sorbian Drežďany, meaning people of the forest. Dresden later evolved into the capital of Saxony.

Early history

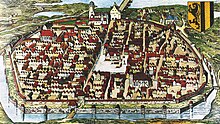

Dresden in 1521

Around the late 12th century, a Slavic settlement called Drežďany[11] (meaning either "Marsh" or "lowland forest-dweller"[12]) had developed on the southern bank. Another settlement existed on the northern bank, but its Slavic name is unknown. It was known as Antiqua Dresdin by 1350, and later as Altendresden,[11][13] both literally "old Dresden". Dietrich, Margrave of Meissen, chose Dresden as his interim residence in 1206, as documented in a record calling the place "Civitas Dresdene".

After 1270, Dresden became the capital of the margraviate. It was given to Friedrich Clem after death of Henry the Illustrious in 1288. It was taken by the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1316 and was restored to the Wettin dynasty after the death of Valdemar the Great in 1319. From 1485, it was the seat of the dukes of Saxony, and from 1547 the electors as well.

Early-modern age

Zwinger, 1719, wedding reception of Augustus III of Poland and Maria Josepha of Austria

The Elector and ruler of Saxony Frederick Augustus I became King Augustus II the Strong of Poland in 1697. He gathered many of the best musicians,[14] architects and painters from all over Europe to the newly named Royal-Polish Residential City of Dresden.[15] His reign marked the beginning of Dresden's emergence as a leading European city for technology and art. During the reign of Kings Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III of Poland most of the city's baroque landmarks were built. These include the Zwinger Royal Palace, the Japanese Palace, the Taschenbergpalais, the Pillnitz Castle and the two landmark churches: the Catholic Hofkirche and the Lutheran Frauenkirche. In addition significant art collections and museums were founded. Notable examples include the Dresden Porcelain Collection, the Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, the Grünes Gewölbe and the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon. In 1729, by decree of King Augustus II the first Polish Military Academy was founded in Dresden. In 1730, it was relocated to Warsaw. Dresden suffered heavy destruction in the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), following its capture by Prussian forces, its subsequent re-capture, and a failed Prussian siege in 1760. Friedrich Schiller wrote his Ode to Joy (the literary base of the European anthem) for the Dresden Masonic lodge in 1785.[citation needed] During the decline of Poland Dresden was site of preparations for the Polish Kościuszko Uprising.

Napoleon Crossing the Elbe by Józef Brodowski (1895)

The city of Dresden had a distinctive silhouette, captured in famous paintings by Bernardo Bellotto and by Norwegian painter Johan Christian Dahl. Between 1806 and 1918 the city was the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony (which was a part of the German Empire from 1871). During the Napoleonic Wars the French emperor made it a base of operations, winning there the famous Battle of Dresden on 27 August 1813. Following the November Uprising (1831) many Poles, including writers Juliusz Słowacki, Stefan Florian Garczyński, Klementyna Hoffmanowa and composer Frédéric Chopin, fled from the Russian Partition of Poland to Dresden. Also national poet Adam Mickiewicz stayed several months in Dresden, starting in March 1832.[16] He wrote the poetic drama Dziady, Part III there. Dresden saw a further influx of Poles after the 1848 and 1863 uprisings, amongst whom were authors Teofil Lenartowicz, Józef Ignacy Kraszewski and Wawrzyniec Benzelstjerna Engeström. Dresden itself was a centre of the German Revolutions in 1848 with the May Uprising, which cost human lives and damaged the historic town of Dresden.[citation needed]

During the 19th century, the city became a major centre of economy, including motor car production, food processing, banking and the manufacture of medical equipment.

In the early 20th century, Dresden was particularly well known for its camera works and its cigarette factories. Between 1918 and 1934, Dresden was capital of the first Free State of Saxony. Dresden was a centre of European modern art until 1933.

Military history

Image of Dresden during the 1890s, before extensive World War II destruction. Landmarks include Dresden Frauenkirche, Augustus Bridge, and Katholische Hofkirche.

During the foundation of the German Empire in 1871, a large military facility called Albertstadt was built.[17] It had a capacity of up to 20,000 military personnel at the beginning of the First World War. The garrison saw only limited use between 1918 and 1934, but was then reactivated in preparation for the Second World War.

Its usefulness was limited by attacks on 17 April 1945[18] on the railway network (especially towards Bohemia).[19] Soldiers had been deployed as late as March 1945 in the Albertstadt garrison.

The Albertstadt garrison became the headquarters of the Soviet 1st Guards Tank Army in the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany after the war. Apart from the German army officers' school (Offizierschule des Heeres), there have been no more military units in Dresden since the army merger during German reunification, and the withdrawal of Soviet forces in 1992. Nowadays, the Bundeswehr operates the Military History Museum of the Federal Republic of Germany in the former Albertstadt garrison.

Second World War

Dresden, 1945, view from the town hall (Rathaus) over the destroyed city (the allegory of goodness in the foreground)

Dresden, 1945—over 90 percent of the city centre was destroyed.

During the Nazi era from 1933 to 1945, the Jewish community of Dresden was reduced from over 6,000 (7,100 people were persecuted as Jews) to 41, as a result of emigration and murders.[20][21] Non-Jews were also targeted, and over 1,300 people were executed by the Nazis at the Münchner Platz, a courthouse in Dresden, including labour leaders, undesirables, resistance fighters and anyone caught listening to foreign radio broadcasts.[22] The bombing stopped prisoners who were busy digging a large hole into which an additional 4,000 prisoners were to be disposed of.[23]

Dresden in the 20th century was a major communications hub and manufacturing centre with 127 factories and major workshops and was designated by the German Military as a defensive strongpoint, with which to hinder the Soviet advance.[24] Being the capital of the German state of Saxony, Dresden not only had garrisons but a whole military borough, the Albertstadt.[citation needed] This military complex, named after Saxon King Albert, was not specifically targeted in the bombing of Dresden, though it was within the expected area of destruction and was extensively damaged.[citation needed]

During the final months of the Second World War, Dresden harboured some 600,000 refugees, with a total population of 1.2 million. Dresden was attacked seven times between 1944 and 1945, and was occupied by the Red Army after the German capitulation.[citation needed]

The bombing of Dresden by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) between 13 and 15 February 1945 remains controversial. On the night of February 13–14, 1945 773 RAF Lancaster bombers dropped 1,181.6 tons of incendiary bombs and 1,477.7 tons of high explosive bombs on the city. The inner city of Dresden was largely destroyed[25][26] The high explosive bombs damaged buildings and exposed their wooden structures, while the incendiaries ignited them, denying their use by retreating German troops and refugees.[citation needed] Widely quoted Nazi propaganda reports claimed 200,000 deaths, but the German Dresden Historians' Commission, made up of 13 prominent German historians, in an official 2010 report published after five years of research concluded that casualties numbered between 18,000 and 25,000.[27]

The Allies described the operation as the legitimate bombing of a military and industrial target.[18] Several researchers have argued that the February attacks were disproportionate. Mostly women and children died.[28] When interviewed after the war in 1977, Sir Arthur Harris stood by his decision to carry out the raids, and reaffirmed that it reduced the German military's ability to wage war.[29]

American author Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughterhouse Five is loosely based on his first-hand experience of the raid as a POW.[30] In remembrance of the victims, the anniversaries of the bombing of Dresden are marked with peace demonstrations, devotions and marches.[31][32]

The destruction of Dresden allowed Hildebrand Gurlitt, a major Nazi museum director and art dealer, to hide a large collection of artwork worth over a billion dollars that had been stolen during the Nazi era, as he claimed it had been destroyed along with his house which was located in Dresden.[33]

Post-war

After the Second World War, Dresden became a major industrial centre in the German Democratic Republic (former East Germany) with a great deal of research infrastructure. It was the centre of Bezirk Dresden (Dresden District) between 1952 and 1990. Many of the city's important historic buildings were reconstructed, including the Semper Opera House and the Zwinger Palace, although the city leaders chose to rebuild large areas of the city in a "socialist modern" style, partly for economic reasons, but also to break away from the city's past as the royal capital of Saxony and a stronghold of the German bourgeoisie. Some of the ruins of churches, royal buildings and palaces, such as the Gothic Sophienkirche, the Alberttheater and the Wackerbarth-Palais, were razed by the Soviet and East German authorities in the 1950s and 1960s rather than being repaired. Compared to West Germany, the majority of historic buildings were saved.[citation needed]

From 1985 to 1990, the future President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, was stationed in Dresden by the KGB, where he worked for Lazar Matveev, the senior KGB liaison officer there. On 3 October 1989 (the so-called "battle of Dresden"), a convoy of trains carrying East German refugees from Prague passed through Dresden on its way to the Federal Republic of Germany. Local activists and residents joined in the growing civil disobedience movement spreading across the German Democratic Republic, by staging demonstrations and demanding the removal of the non-democratic government.

Post-reunification

The Dresden Frauenkirche, a few years after its reconsecration

Dresden old town

Dresden Frauenkirche at night

Dresden has experienced dramatic changes since the reunification of Germany in the early 1990s. The city still bears many wounds from the bombing raids of 1945, but it has undergone significant reconstruction in recent decades. Restoration of the Dresden Frauenkirche was completed in 2005, a year before Dresden's 800th anniversary, notably by privately raised funds. The gold cross on the top of the church was funded officially by "the British people and the House of Windsor". The urban renewal process, which includes the reconstruction of the area around the Neumarkt square on which the Frauenkirche is situated, will continue for many decades, but public and government interest remains high, and there are numerous large projects underway—both historic reconstructions and modern plans—that will continue the city's recent architectural renaissance. Prominently, the Dresden Frauenkirche, a Lutheran church, began to be rebuilt after the reunification of Germany in 1994. Both exterior and interior reconstruction were completed by 2005.

Dresden remains a major cultural centre of historical memory, owing to the city's destruction in World War II. Each year on 13 February, the anniversary of the British and American fire-bombing raid that destroyed most of the city, tens of thousands of demonstrators gather to commemorate the event. Since reunification, the ceremony has taken on a more neutral and pacifist tone (after being used more politically during the Cold War). Beginning in 1999, right-wing Neo-Nazi white nationalist groups have organised demonstrations in Dresden that have been among the largest of their type in the post-war history of Germany. Each year around the anniversary of the city's destruction, people convene in the memory of those who died in the fire-bombing.

The completion of the reconstructed Dresden Frauenkirche in 2005 marked the first step in rebuilding the Neumarkt area. The areas around the square have been divided into 8 "Quarters", with each being rebuilt as a separate project, the majority of buildings to be rebuilt either to the original structure or at least with a façade similar to the original. Quarter I and the front section of Quarters II, III, IV and V(II) have since been completed, with Quarter VIII currently under construction.

In 2002, torrential rains caused the Elbe to flood 9 metres (30 ft) above its normal height, i.e., even higher than the old record height from 1845, damaging many landmarks (See 2002 European flood). The destruction from this "millennium flood" is no longer visible, due to the speed of reconstruction.

The United Nations' cultural organization UNESCO declared the Dresden Elbe Valley to be a World Heritage Site in 2004.[34] After being placed on the list of endangered World Heritage Sites in 2006, the city lost the title in June 2009,[35][36] due to the construction of the Waldschlößchenbrücke, making it only the second ever World Heritage Site to be removed from the register.[35][36] UNESCO stated in 2006 that the bridge would destroy the cultural landscape. The city council's legal moves, meant to prevent the bridge from being built, failed.[37][38]

Geography

Location

Saxon Switzerland a few kilometres outside of Dresden

View over Dresden Basin

Dresden lies on both banks of the Elbe River, mostly in the Dresden Basin, with the further reaches of the eastern Ore Mountains to the south, the steep slope of the Lusatian granitic crust to the north, and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains to the east at an altitude of about 113 metres (371 feet). Triebenberg is the highest point in Dresden at 384 metres (1,260 feet).[39]

With a pleasant location and a mild climate on the Elbe, as well as Baroque-style architecture and numerous world-renowned museums and art collections, Dresden has been called "Elbflorenz" (Florence of the Elbe).

The incorporation of neighbouring rural communities over the past 60 years has made Dresden the twelfth largest urban district by area in Germany after Berlin, Hamburg and Cologne.[40]

The nearest German cities are Chemnitz 80 kilometres (50 miles) to the southwest, Leipzig 100 kilometres (62 miles) to the northwest and Berlin 200 kilometres (120 miles) to the north. Prague, Czech Republic is about 150 kilometres (93 miles) to the south and to the east 200 kilometres (120 miles) is the Polish city of Wrocław.

Nature

Dresden is one of the greenest cities in all of Europe, with 63% of the city being green areas and forests. The Dresden Heath (Dresdner Heide) to the north is a forest 50 km2 in size. There are four nature reserves. The additional Special Conservation Areas cover 18 km2. The protected gardens, parkways, parks and old graveyards host 110 natural monuments in the city.[41] The Dresden Elbe Valley is a former world heritage site which is focused on the conservation of the cultural landscape in Dresden. One important part of that landscape is the Elbe meadows, which cross the city in a 20 kilometre swath. Saxon Switzerland is an important nearby location.

Climate

Like many places in Eastern parts of Germany, Dresden has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb), with significant continental influences due to its inland location. The summers are warm, averaging 19.0 °C (66.2 °F) in July. The winters are slightly colder than the German average, with a January average temperature of 0.1 °C (32.18 °F), just preventing it from being a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb). The driest months are February, March and April, with precipitation of around 40 mm (1.6 in). The wettest months are July and August, with more than 80 mm (3.1 in) per month.

The microclimate in the Elbe valley differs from that on the slopes and in the higher areas, where the Dresden district Klotzsche, at 227 metres above sea level, hosts the Dresden weather station. The weather in Klotzsche is 1 to 3 °C (1.8 to 5.4 °F) colder than in the inner city at 112 metres above sea level.

| Climate data for Dresden, Germany for 1981–2010, record temperatures for 1967-2013 (Source: DWD) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) | 19.7 (67.5) | 24.4 (75.9) | 29.5 (85.1) | 31.3 (88.3) | 35.3 (95.5) | 36.4 (97.5) | 37.3 (99.1) | 32.3 (90.1) | 27.1 (80.8) | 19.1 (66.4) | 16.4 (61.5) | 37.3 (99.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) | 3.9 (39) | 8.3 (46.9) | 13.7 (56.7) | 18.9 (66) | 21.5 (70.7) | 24.2 (75.6) | 23.8 (74.8) | 18.9 (66) | 13.6 (56.5) | 7.2 (45) | 3.5 (38.3) | 13.3 (55.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.1 (32.2) | 0.9 (33.6) | 4.5 (40.1) | 9.0 (48.2) | 14.0 (57.2) | 16.7 (62.1) | 19.0 (66.2) | 18.6 (65.5) | 14.3 (57.7) | 9.8 (49.6) | 4.5 (40.1) | 1.1 (34) | 9.4 (48.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) | −1.9 (28.6) | 1.2 (34.2) | 4.4 (39.9) | 8.9 (48) | 11.9 (53.4) | 14.0 (57.2) | 13.9 (57) | 10.4 (50.7) | 6.5 (43.7) | 2.1 (35.8) | −1.2 (29.8) | 5.7 (42.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.3 (−13.5) | −23.0 (−9.4) | −16.5 (2.3) | −6.3 (20.7) | −3.4 (25.9) | 1.2 (34.2) | 6.7 (44.1) | 5.4 (41.7) | 1.4 (34.5) | −6.0 (21.2) | −13.2 (8.2) | −21.0 (−5.8) | −25.3 (−13.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 46.5 (1.831) | 34.6 (1.362) | 43.2 (1.701) | 41.2 (1.622) | 64.8 (2.551) | 64.6 (2.543) | 87.4 (3.441) | 83.0 (3.268) | 50.2 (1.976) | 42.5 (1.673) | 53.9 (2.122) | 52.1 (2.051) | 664.03 (26.1429) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.1 | 77.8 | 118.2 | 170.7 | 218.7 | 202.3 | 222.6 | 212.9 | 152.0 | 122.4 | 64.5 | 55.1 | 1,679.37 |

| Source: Data derived from Deutscher Wetterdienst[42] | |||||||||||||

Flood protection

Because of its location on the banks of the Elbe, into which some water sources from the Ore Mountains flow, flood protection is important. Large areas are kept free of buildings to provide a flood plain. Two additional trenches, about 50 metres wide, have been built to keep the inner city free of water from the Elbe, by dissipating the water downstream through the inner city's gorge portion. Flood regulation systems like detention basins and water reservoirs are almost all outside the city area.

The Weißeritz, normally a rather small river, suddenly ran directly into the main station of Dresden during the 2002 European floods. This was largely because the river returned to its former route; it had been diverted so that a railway could run along the river bed.

Many locations and areas need to be protected by walls and sheet pilings during floods. A number of districts become waterlogged if the Elbe overflows across some of its former floodplains.

Floods in 2002

Semperoper during 2005 floods

Elbe Flood in April 2006

Dresden skyline in 2006

Dresden under water in June 2013

City structuring

Großer Garten in Dresden

Dresden is a spacious city. Its districts differ in their structure and appearance. Many parts still contain an old village core, while some quarters are almost completely preserved as rural settings. Other characteristic kinds of urban areas are the historic outskirts of the city, and the former suburbs with scattered housing. During the German Democratic Republic, many apartment blocks were built. The original parts of the city are almost all in the districts of Altstadt (Old town) and Neustadt (New town). Growing outside the city walls, the historic outskirts were built in the 18th century. They were planned and constructed on the orders of the Saxon monarchs, which is why the outskirts are often named after sovereigns. From the 19th century the city grew by incorporating other districts. Dresden has been divided into ten districts called "Ortsamtsbereich" and nine former boroughs ("Ortschaften") which have been incorporated.

Demographics

Top 10 non-German populations[43] | |

| Nationality | Population (31.12.2016) |

|---|---|

| 2,417 | |

| 2,312 | |

| 2,195 | |

| 1,743 | |

| 1,630 | |

| 1,592 | |

| 1,099 | |

| 1,076 | |

| 982 | |

| 950 | |

The population of Dresden grew to 100,000 inhabitants in 1852, making it one of the first German cities after Hamburg and Berlin to reach that number. The population peaked at 649,252 in 1933, and dropped to 450,000 in 1946 because of World War II, during which large residential areas of the city were destroyed. After large incorporations and city restoration, the population grew to 522,532 again between 1950 and 1983.[44]

Since German reunification, demographic development has been very unsteady. The city has struggled with migration and suburbanisation. During the 1990s the population increased to 480,000 because of several incorporations, and decreased to 452,827 in 1998. Between 2000 and 2010, the population grew quickly by more than 45,000 inhabitants (about 9.5%) due to a stabilised economy and re-urbanisation. Along with Munich and Potsdam, Dresden is one of the ten fastest-growing cities in Germany,[40] while the population of the surrounding new federal states is still shrinking.[44][45]

As of 2010[update] the population of the city of Dresden was 523,058,[46] the population of the Dresden agglomeration was 780,561 as of 2008[update],[47] and as of 2007[update] the population of the Dresden region, which includes the neighbouring districts of Meißen, Sächsische Schweiz-Osterzgebirge and the western part of the district of Bautzen was 1,143,197.[48] Dresden is one of the few German Cities which has more inhabitants than ever since World War II.

As of 2016 about 50.2% of the population was female.[49] As of 2007[update] the mean age of the population was 43 years, which is the lowest among the urban districts in Saxony.[50] As of 31 December 2013[update] there were 34,7277 people with a migration background (6.3% of the population, down from 8.7% in 2013), and about half, 25,224 or about 3.6% of all Dresden citizens were foreigners.[49] This percentage is down from 4.7% in 2013.

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| Germans | 91% |

| Other European | 5% |

| Turkish | 0.2% |

| Asians | 1% |

| Africans | 0.7% |

| Other/Mixed | 2.1% |

Governance

Dresden is one of Germany's 16 political centres and the capital of Saxony. It has institutions of democratic local self-administration that are independent from the capital functions.[51] Some local affairs of Dresden receive national attention.

Dresden hosted some international summits such as the Petersburg Dialogue between Russia and Germany, the European Union's Minister of the Interior conference and the G8 labour ministers conference in recent years.[citation needed]

Municipality and city council

The city council defines the basic principles of the municipality by decrees and statutes. The council gives orders to the "Bürgermeister" ("Burgomaster" or Mayor) by voting for resolutions and thus has some executive power.[52]

As of 2008[update], there was no stable governing majority on Dresden city council (Stadtrat).[53]

As of 2014[update] the 70 seats of the city council were distributed as follows:[54]

| Party | Number of seats |

|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Union (Germany) | 21 |

| Die Linke. | 15 |

| Bündnis 90/Die Grünen | 11 |

| Social Democratic Party of Germany | 9 |

| Alternative for Germany | 5 |

| Free Democratic Party (Germany) | 3 |

| National Democratic Party of Germany | 2 |

| Bündnis Freie Bürger | 2 |

| Pirate Party Germany | 2 |

The Supreme Burgomaster is directly elected by the citizens for a term of seven years. Executive functions are normally elected indirectly in Germany. However, the Supreme Burgomaster shares numerous executive rights with the city council. He/She is the executive head of the municipality, and also the ceremonial representative of the city. The main departments of the municipality are managed by seven burgomasters.[55]

Local affairs

The Waldschlösschen Bridge is a subject of controversy in Dresden and other parts of Germany

Local affairs in Dresden often centre around the urban development of the city and its spaces. Architecture and the design of public places is a controversial subject. Discussions about the Waldschlößchenbrücke, a bridge under construction across the Elbe, received international attention because of its position across the Dresden Elbe Valley World Heritage Site. The city held a public referendum in 2005 on whether to build the bridge, prior to UNESCO expressing doubts about the compatibility between bridge and heritage. Its construction caused loss of World Heritage site status in 2009.[56]

In 2006 Dresden sold its publicly subsidized housing organization, WOBA Dresden GmbH, to the US-based private investment company Fortress Investment Group. The city received 987.1 million euro and paid off its remaining loans, making it the first large city in Germany to become debt-free. Opponents of the sale were concerned about Dresden's loss of control over the subsidized housing market.[57]

Since October 2014, PEGIDA, a nationalistic political movement based in Dresden has been organising weekly demonstrations against what it perceives as the Islamisation of Europe although the primarily Turkish and Muslim population make up only 0.2% of the population of the city. As the number of demonstrators increased to 17,500 on December 22, so has the international media coverage of it.[58]

Twin towns – sister cities

Along with its twin city Coventry in England, Dresden was one of the first two cities to pair with a foreign city after the Second World War.[citation needed] The cities became twins after the war in an act of reconciliation, as both had suffered near-total destruction from massive aerial bombing.[citation needed] Similar symbolism occurred in 1988, when Dresden twinned with the Dutch city of Rotterdam. The Coventry Blitz and Rotterdam Blitz bombardments by the German Luftwaffe are also considered to be disproportional.[citation needed]

Dresden has had a triangular partnership with Saint Petersburg and Hamburg since 1987. Dresden has 14 twin cities.[59]

Coventry, West Midlands, England, United Kingdom, since 1959[60][61]

Coventry, West Midlands, England, United Kingdom, since 1959[60][61]

Saint Petersburg, Russia, since 1961

Saint Petersburg, Russia, since 1961

Wrocław, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland, since 1963

Wrocław, Lower Silesian Voivodeship, Poland, since 1963

Skopje, Macedonia, since 1967[62]

Skopje, Macedonia, since 1967[62]

Ostrava, Czech Republic, since 1971

Ostrava, Czech Republic, since 1971

Brazzaville, Congo, since 1975

Brazzaville, Congo, since 1975

Florence, Tuscany, Italy, since 1978

Florence, Tuscany, Italy, since 1978

Hamburg, Germany, since 1987[63]

Hamburg, Germany, since 1987[63]

Rotterdam, South Holland, Netherlands, since 1988

Rotterdam, South Holland, Netherlands, since 1988

Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Grand Est, France, since 1990[64]

Strasbourg, Bas-Rhin, Grand Est, France, since 1990[64]

Salzburg, Austria, since 1991

Salzburg, Austria, since 1991

Columbus, Ohio, United States, since 1992

Columbus, Ohio, United States, since 1992

Hangzhou, China, since 2009

Hangzhou, China, since 2009

Culture and architecture

Dresden at night

Dresden Frauenkirche, symbol of Dresden

Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner had a number of their works performed for the first time in Dresden.[citation needed] Other famous artists, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Otto Dix, Oskar Kokoschka, Richard Strauss, Gottfried Semper and Gret Palucca, were also active in the city.[citation needed] Dresden is also home to several important art collections, world-famous musical ensembles, and significant buildings from various architectural periods, many of which were rebuilt after the destruction of the Second World War.[citation needed]

Entertainment

The Semperoper, completely rebuilt and reopened in 1985

Yenidze

The Saxon State Opera descends from the opera company of the former electors and Kings of Saxony. Their first opera house was the Opernhaus am Taschenberg, opened in 1667. The Opernhaus am Zwinger presented opera from 1719 to 1756, when the Seven Years' War began. The later Semperoper was completely destroyed during the bombing of Dresden during the second world war. The opera's reconstruction was completed exactly 40 years later, on 13 February 1985. Its musical ensemble is the Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden, founded in 1548.[65] The Dresden State Theatre runs a number of smaller theatres. The Dresden State Operetta is the only independent operetta in Germany.[66] The Herkuleskeule (Hercules club) is an important site in German-speaking political cabaret.

There are several choirs in Dresden, the best-known of which is the Dresdner Kreuzchor (Choir of The Holy Cross). It is a boys' choir drawn from pupils of the Kreuzschule, and was founded in the 13th century.[67] The Dresdner Kapellknaben are not related to the Staatskapelle, but to the former Hofkapelle, the Catholic cathedral, since 1980. The Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra is the orchestra of the city of Dresden.[citation needed]

Throughout the summer, the outdoor concert series "Zwingerkonzerte und Mehr" is held in the Zwingerhof. Performances include dance and music.[68]

A big event each year in June is the Bunte Republik Neustadt,[69] a culture festival lasting 3 days in the city district of Dresden-Neustadt. Bands play live concerts for free in the streets and people can find all kinds of refreshments and food.

Museums, presentations and collections

Dresden hosts the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) which, according to the institution's own statements, place it among the most important museums presently in existence. The art collections consist of twelve museums, of which the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Gallery) and the Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault) and the Japanese Palace (Japanisches Palais) are the most famous.[70] Also known are Galerie Neue Meister (New Masters Gallery), Rüstkammer (Armoury) with the Turkish Chamber, and the Museum für Völkerkunde Dresden (Museum of Ethnology).

Other museums and collections owned by the Free State of Saxony in Dresden are:

- The Deutsche Hygiene-Museum, founded for mass education in hygiene, health, human biology and medicine[71]

- The Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte (State Museum of Prehistory)[72]

- The Staatliche Naturhistorische Sammlungen Dresden (State Collection of Natural History)[citation needed]

- The Universitätssammlung Kunst + Technik (Collection of Art and Technology of the Dresden University of Technology)[citation needed]

Verkehrsmuseum Dresden (Transport Museum)

Festung Dresden (Dresden Fortress)[73][74]

Panometer Dresden (Dresden Panometer) (Panorama museum)[75][76]

The Dresden City Museum is run by the city of Dresden and focused on the city's history. The Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr (Military History Museum) is placed in the former garrison in the Albertstadt.[citation needed]

The book museum of the Saxon State Library presents the famous Dresden Codex.[77]

The Botanischer Garten Dresden is a botanical garden in the Großer Garten that is maintained by the Dresden University of Technology. Also located in the Großer Garten is the Dresden Zoo.

The Kraszewski-Museum is a museum dedicated to the most prolific Polish writer Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, who lived in Dresden from 1863 to 1883.

Architecture

Although Dresden is often said to be a Baroque city, its architecture is influenced by more than one style. Other eras of importance are the Renaissance and Historism, as well as the contemporary styles of Modernism and Postmodernism.[citation needed]

Dresden has some 13 000 listed cultural monuments and eight districts under general preservation orders.[78]

Royal household

Zwinger Palace

The royal buildings are among the most impressive buildings in Dresden. The Dresden Castle was the seat of the royal household from 1485. The wings of the building have been renewed, built upon and restored many times. Due to this integration of styles, the castle is made up of elements of the Renaissance, Baroque and Classicist styles.[79]

The Zwinger Palace is across the road from the castle. It was built on the old stronghold of the city and was converted to a centre for the royal art collections and a place to hold festivals. Its gate by the moat, surmounted by a golden crown, is famous.[80]

Other royal buildings and ensembles:

Brühl's Terrace was a gift to Heinrich, count von Brühl, and became an ensemble of buildings above the river Elbe.

Dresden Elbe Valley with the Pillnitz Castle and other castles

Sacred buildings

Bernardo Bellotto's Dresden included the Hofkirche during construction.

The Hofkirche was the church of the royal household. Augustus the Strong, who desired to be King of Poland, converted to Catholicism, as Polish kings had to be Catholic. At that time Dresden was strictly Protestant. Augustus the Strong ordered the building of the Hofkirche, the Roman Catholic Cathedral, to establish a sign of Roman Catholic religious importance in Dresden. The church is the cathedral "Sanctissimae Trinitatis" since 1980. The crypt of the Wettin Dynasty is located within the church.[81] King Augustus III of Poland is buried in the Cathedral, as one of very few Polish Kings to be buried outside the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.

In contrast to the Hofkirche, the Lutheran Frauenkirche was built almost contemporaneously by the citizens of Dresden. It is said to be the greatest cupola building in Central and Northern Europe. The city's historic Kreuzkirche was reconsecrated in 1388.[82]

There are also other churches in Dresden, for example a Russian Orthodox Church in the Südvorstadt district.[citation needed]

Contemporary architecture

The locally controversial UFA-Palast

Dresden has been an important site for the development of contemporary architecture for centuries, and this trend has continued into the 20th and 21st centuries.[citation needed]

Historicist buildings made their presence felt on the cityscape until the 1920s sampled by public buildings such as the Staatskanzlei or the City Hall. One of the youngest buildings of that era is the Hygiene Museum, which is designed in an impressively monumental style, but employs plain façades and simple structures. It is often attributed, wrongly, to the Bauhaus school.[citation needed]

Most of the present cityscape of Dresden was built after 1945, a mix of reconstructed or repaired old buildings and new buildings in the modern and postmodern styles. Important buildings erected between 1945 and 1990 are the Centrum-Warenhaus (a large department store) representing the international Style, the Kulturpalast, and several smaller and two bigger complexes of Plattenbau housing in Gorbitz, while there is also housing dating from the era of Stalinist architecture.[citation needed]

The New Synagogue

After 1990 and German reunification, new styles emerged. Important contemporary buildings include the New Synagogue, a postmodern building with few windows, the Transparent Factory, the Saxon State Parliament and the New Terrace, the UFA-Kristallpalast cinema by Coop Himmelb(l)au (one of the biggest buildings of Deconstructivism in Germany), and the Saxon State Library. Daniel Libeskind and Norman Foster both modified existing buildings. Foster roofed the main railway station with translucent Teflon-coated synthetics. Libeskind changed the whole structure of the Bundeswehr Military History Museum Museum by placing a wedge through the historical arsenal building.[citation needed]

Other buildings

The gilded equestrian sculpture of August the Strong of Poland and Saxony

Other buildings include important bridges crossing the Elbe river, the Blaues Wunder bridge and the Augustusbrücke, which is on the site of the oldest bridge in Dresden.

There are about 300 fountains and springs, many of them in parks or squares. The wells serve only a decorative function, since there is a fresh water system in Dresden. Springs and fountains are also elements in contemporary cityspaces.[citation needed]

The most famous sculpture in Dresden is Jean-Joseph Vinache's golden equestrian sculpture of August the Strong called the Goldener Reiter (Golden Cavalier) on the Neustädter Markt square. It shows August at the beginning of the Hauptstraße (Main street) on his way to Warsaw, where he was King of Poland in personal union. Another sculpture is the memorial of Martin Luther in front of the Frauenkirche.[citation needed]

Dresden-Hellerau—Germany's first garden city

The Garden City of Hellerau, at that time a suburb of Dresden, was founded in 1909. In 1911 Heinrich Tessenow built the Hellerau Festspielhaus (festival theatre) and Hellerau became a centre of modernism with international standing until the outbreak of World War I.[citation needed]

In 1950, Hellerau was incorporated into the city of Dresden. Today the Hellerau reform architecture is recognized as exemplary. In the 1990s, the garden city of Hellerau became a conservation area.[citation needed]

Living quarters

Dresden's urban parts are subdivided in rather a lot of city quarters, up to around 100, among them relatively many larger villa quarters dominated by historic multiple dwelling units, especially, but not only along the river, most known are Blasewitz, Loschwitz, Pillnitz and Weißer Hirsch. Also some Art Nouveau living quarters and two bigger quarters typical for communist architecture – but much renovated – can be found. The villa town of Radebeul joins the Dresden city tram system, which is expansive due to the lack of an underground system.[citation needed]

Cinemas and cinematics

There are several small cinemas presenting cult films and low-budget or low-profile films chosen for their cultural value. Dresden also has a few multiplex cinemas, of which the Rundkino is the oldest.[citation needed]

Dresden has been a centre for the production of animated films and optical cinematic techniques.[citation needed]

Sport

The Glücksgas Stadium, the current home of Dynamo Dresden

Dresden is home to Dynamo Dresden, which had a tradition in UEFA club competitions up to the early 1990s. Dynamo Dresden won eight titles in the DDR-Oberliga. Currently, the club is a member of the 2. Bundesliga after some seasons in the Bundesliga and 3rd Liga.[83]

In the early 20th century, the city was represented by Dresdner SC, who were one of Germany's most successful clubs in football. Their best performances came during World War II, when they were twice German champions, and twice Cup winners. Dresdner SC is a multisport club. While its football team plays in the sixth-tier Landesliga Sachsen, its volleyball section has a team in the women's Bundesliga. Dresden has a third football team SC Borea Dresden.

ESC Dresdner Eislöwen is an ice hockey club playing in the 2nd Bundesliga again. Dresden Monarchs are an American football team in the German Football League.[citation needed]

The Dresden Titans are the city's top basketball team. Due to good performances, they have moved up several divisions and currently play in Germany's second division ProA. The Titans' home arena is the Margon Arena.

Since 1890, horse races have taken place and the Dresdener Rennverein 1890 e.V. are active and one of the big sporting events in Dresden.[84]

Major sporting facilities in Dresden are the Glücksgas Stadium, the Heinz-Steyer-Stadion and the EnergieVerbund Arena for ice hockey.

Main sights

Dresden Frauenkirche

Zwinger Palace

Semperoper

Dresden New Town Hall

Dresden old town

Dresden Academy of Fine Arts

Kreuzkirche, Dresden

Dresden Frauenkirche

Fürstenzug

Münzgasse at Neumarkt

View over Altmarkt (Old market) during Striezelmarkt

Dresden at night

Dresden Castle

Katholische Hofkirche

Yenidze at night

Dresden TV tower

Pillnitz Castle

German Hygiene Museum

Bundeswehr Military History Museum

Blue Wonder

Dresden Central Station

Infrastructure

Transport

The longest trams in Dresden set a record in length

The Bundesautobahn 4 (European route E40) crosses Dresden in the northwest from west to east. The Bundesautobahn 17 leaves the A4 in a south-eastern direction. In Dresden it begins to cross the Ore Mountains towards Prague. The Bundesautobahn 13 leaves from the three-point interchange "Dresden-Nord" and goes to Berlin. The A13 and the A17 are on the European route E55. Several Bundesstraße roads crossing or running through Dresden.

There are two main inter-city transit hubs in the railway network in Dresden: Dresden Hauptbahnhof and Dresden-Neustadt railway station. The most important railway lines run to Berlin, Prague, Leipzig and Chemnitz. A commuter train system (Dresden S-Bahn) operates on three lines alongside the long-distance routes.

Dresden Airport is the city's international airport, located at the north-western outskirts of the town. Its infrastructure has been improved[when?] with new terminals and a motorway access route.

Dresden Central Station is the main inter-city transport hub

Dresden has a large tramway network operated by Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe, the municipal transport company. Because the geological bedrock does not allow the building of underground railways,[citation needed] the tramway is an important form of public transport. The Transport Authority operates twelve lines on a 200 km (124 mi) network.[85] Many of the new low-floor vehicles are up to 45 metres long and produced by Bombardier Transportation in Bautzen. While about 30% of the system's lines are on reserved track (often sown with grass to avoid noise), many tracks still run on the streets, especially in the inner city.[86]

The CarGoTram is a tram that supplies Volkswagen's Transparent Factory, crossing the city. The transparent factory is located not far from the city centre next to the city's largest park.[87]

The districts of Loschwitz and Weisser Hirsch are connected by the Dresden Funicular Railway, which has been carrying passengers back and forth since 1895.[88][citation needed]

Public utilities

The Sächsische Staatskanzlei (Saxon State Chancellery) is an institution assisting the President of the State

Dresden is the capital of a German Land (federal state). It is home to the Landtag of Saxony[89] and the ministries of the Saxon Government. The controlling Constitutional Court of Saxony is in Leipzig. The highest Saxon court in civil and criminal law, the Higher Regional Court of Saxony, has its home in Dresden.[90]

Most of the Saxon state authorities are located in Dresden. Dresden is home to the Regional Commission of the Dresden Regierungsbezirk, which is a controlling authority for the Saxon Government. It has jurisdiction over eight rural districts, two urban districts and the city of Dresden.[citation needed]

Like many cities in Germany, Dresden is also home to a local court, has a trade corporation and a Chamber of Industry and Trade and many subsidiaries of federal agencies (such as the Federal Labour Office or the Federal Agency for Technical Relief). It hosts some divisions of the German Customs and the eastern Federal Waterways Directorate.[citation needed]

Dresden is home to a military subdistrict command, but no longer has large military units as it did in the past. Dresden is the traditional location for army officer schooling in Germany, today carried out in the Offizierschule des Heeres.[citation needed]

Economy

Advanced Micro Devices factory

The International Congress Center Dresden

Until famous enterprises like Dresdner Bank left Dresden in the communist era to avoid nationalisation, Dresden was one of the most important German cities, an important industrial centre of the German Democratic Republic.[citation needed] The period of the GDR until 1990 was characterized by low economic growth in comparison to western German cities.[citation needed]

In 1990 Dresden had to struggle with the economic collapse of the Soviet Union and the other export markets in Eastern Europe. After reunification enterprises and production sites broke down almost completely as they entered the social market economy, facing competition from the Federal Republic of Germany. After 1990 a completely new legal system and currency system was introduced and infrastructure was largely rebuilt with funds from the Federal Republic of Germany. Dresden as a major urban centre has developed much faster and more consistently than most other regions in the former German Democratic Republic, but it still faces many social and economic problems stemming from the collapse of the former system, including high unemployment levels.[citation needed]

Between 1990 and 2010 the unemployment rate fluctuated between 13% and 15% and is still relatively high, with a low of 8.9% in May 2012.[91] Dresden has raised its GDP per capita to 31,100 euro, close to the GDP per capita of some West German communities (the average of the 50 biggest cities is around 35,000 euro).[92]

Thanks to the presence of public administration centres, a high density of semi-public research institutes and an extension of publicly funded high technology sectors, the proportion of highly qualified workers Dresden is again among the highest in Germany and by European criteria. Dresden regularly ranks among the best ten bigger cities in Germany to live in.[citation needed]

Transparent Factory owned by Volkswagen

Enterprises

Three major sectors dominate Dresden's economy:

Silicon Saxony Saxony's semiconductor industry was built up in 1969. Major enterprises today are AMD's spin-off GLOBALFOUNDRIES, Infineon Technologies, ZMDI and Toppan Photomasks. Their factories attract many suppliers of material and cleanroom technology enterprises to Dresden.

The pharmaceutical sector developed at the end of the 19th century. The 'Sächsisches Serumwerk Dresden' (Saxon Serum Plant, Dresden), owned by GlaxoSmithKline, is a global leader in vaccine production.[citation needed] Another traditional pharmaceuticals producer is Arzneimittelwerke Dresden (Pharmaceutical Works, Dresden).[citation needed]

A third traditional branch is that of mechanical and electrical engineering. Major employers are the Volkswagen Transparent Factory, EADS Elbe Flugzeugwerke (Elbe Aircraft Works), Siemens and Linde-KCA-Dresden.[citation needed]The tourism industry enjoys high revenue and supports many employees. There are around one hundred bigger hotels in Dresden, many of which cater in the upscale range.[citation needed] Dresden still has a shortage of corporate headquarters.[citation needed]

Media

The media sector is not particularly strong in Dresden.[citation needed]

The media in Dresden include two major newspapers of regional record: the Sächsische Zeitung (Saxon Newspaper, circulation around 228,000) and the Dresdner Neueste Nachrichten (Dresden's Latest News, circulation around 50,000). Dresden has a broadcasting centre belonging to the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. The Dresdner Druck- und Verlagshaus (Dresden printing plant and publishing house) produces part of Spiegel's print run, amongst other newspapers and magazines.[citation needed]

Education and science

Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden

Universities

Dresden is home to a number of renowned universities, but among German cities it is a more recent location for academic education.

- The Dresden University of Technology (Technische Universität Dresden) with more than 36,000 students (2011)[93] was founded in 1828 and is among the oldest and largest Universities of Technology in Germany. It is currently the university of technology in Germany with the largest number of students but also has many courses in social studies, economics and other non-technical sciences. It offers 126 courses. In 2006, the TU Dresden was successful in the German Universities Excellence Initiative of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Germany).

- The Dresden University of Technology founded a Kids-University in 2004.[citation needed]

- The Dresden University of Applied Sciences (Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Dresden) was founded in 1992 and had about 5,300 students in 2005.[94]

- The Dresden Academy of Fine Arts (Hochschule für Bildende Künste Dresden) was founded in 1764 and is known for its former professors and artists such as George Grosz, Sascha Schneider, Otto Dix, Oskar Kokoschka, Bernardo Bellotto, Carl-Gustav Carus, Caspar David Friedrich and Gerhard Richter.

- The Palucca School of Dance (Palucca Hochschule für Tanz)[95] was founded by Gret Palucca in 1925 and is a major European school of free dance.

- The Carl Maria von Weber College of Music was founded in 1856.

Other universities include the "Hochschule für Kirchenmusik", a school specialising in church music, the "Evangelische Hochschule für Sozialarbeit", an education institution for social work.[citation needed] The "Dresden International University" is a private postgraduate university, founded a few years ago[when?] in cooperation with the Dresden University of Technology.[citation needed]

Dresden World Trade Centre at night

Research institutes

Dresden hosts many research institutes, some of which have gained an international standing.[citation needed] The domains of most importance are micro- and nanoelectronics, transport and infrastructure systems, material and photonic technology, and bio-engineering. The institutes are well connected among one other as well as with the academic education institutions.[citation needed]

Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf is the largest complex of research facilities in Dresden, a short distance outside the urban areas. It focuses on nuclear medicine and physics. As part of the Helmholtz Association it is one of the German Big Science research centres.

The Max Planck Society focuses on fundamental research. In Dresden there are three Max Planck Institutes (MPI); the "MPI of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics", the "MPI for Chemical Physics of Solids" and the "MPI for the Physics of Complex Systems".[96]

The Fraunhofer Society hosts institutes of applied research that also offer mission-oriented research to enterprises. With eleven institutions or parts of institutes, Dresden is the largest location of the Fraunhofer Society worldwide.[97] The Fraunhofer Society has become an important factor in location decisions and is seen as a useful part of the "knowledge infrastructure".[citation needed]

The Leibniz Community is a union of institutes with science covering fundamental research and applied research. In Dresden there are three Leibniz Institutes. The "Leibniz Institute for Polymer Research"[98] and the "Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research"[99] are both in the material and high-technology domain, while the "Leibniz Institute for Ecological and Regional Development" is focused on more fundamental research into urban planning.[citation needed]Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf was member of the Leibniz Community until the end of 2010.[citation needed]

Higher secondary education

Dresden has[when?] more than 20 Gymnasien which prepare for a tertiary education, five of which are private.[100] The "Sächsisches Landesgymnasium für Musik" with a focus on music is supported, as its name implies by the State of Saxony, rather than by the city.[101] There are some Berufliche Gymnasien which combine vocational education and secondary education and a Abendgymnasium which prepares higher education of adults avocational.[102]

Sons and daughters of the town

Georg Bartisch (ca 1535–1607), eye surgeon and author of first German-language textbook of ophthalmology

- Christine Bergmann (born 1939), politician (SPD)

August Buchner (1591–1661), influential Baroque poet

Carle Hessay (1911–1978), Canadian painter

Erich Kästner (1899–1974), author of books

Victor Klemperer (1881–1960) Jewish author of I Will Bear Witness

Siarhei Mikhalok (born 1972), Belarusian rock musician and actor- Wolfgang Mischnick (1921–2002), politician FDP

Karl Reinisch (1921–2007), engineer

Gerhard Richter (born 1932), painter

Helmut Schön (1915–1996), football trainer, lead Germany to world championship in 1974

Herbert Wehner (1906–1990), politician SPD

Honourary Citizens

Martin Mutschmann, 11.05.1933 (revoked 26.06.1945)[103]

Notes

^ "Aktuelle Einwohnerzahlen nach Gemeinden 2017] (Einwohnerzahlen auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011)" (PDF). Statistisches Landesamt des Freistaates Sachsen (in German). October 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Designated by article 2 of the "Saxon Constitution". Archived from the original on 31 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ http://www.leipzig.de/news/news/leipzigs-einwohnerzahl-knackt-die-570-000/

^ http://www.dresden.de/de/wirtschaft/wirtschaftsstandort-dresden.php

^ http://www.xn--stdteranking-hcb.de/deutschland_dresden.php

^ http://www.dresden.de/de/leben/stadtportrait/statistik/wirtschaft-finanzen/tourismus.php

^ http://www.lvz.de/Leipzig/Lokales/Staedteranking-Leipzig-landet-auf-Platz-zwei

^ http://www.dnn.de/Dresden/Lokales/HWWI-Staedteranking-Dresden-mit-grossem-Potenzial-auf-Platz-vier

^ ab Dresden.de. "Prehistoric times", City of Dresden, n.d. Archived 19 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

^ Rengert Elburg: Man-animal relationships in the Early Neolithic of Dresden (Saxony, Germany)

^ ab Fritz Löffler, Das alte Dresden, Leipzig 1982, p.20

^ Ernst Eichler und Hans Walther: Sachsen. Alle Städtenamen und deren Geschichte. Faber und Faber Verlag, Leipzig 2007,

ISBN 978-3-86730-038-4, S. 54 f.

^ Geschichtlicher Hintergrund des Jubiläums "600 Jahre Stadtrecht Altendresden" (German)

^ Dresden in the Time of Zelenka and Hasse

^ http://www.sachsen-tourismus.de/pl/regiony/regiony-i-miasta/drezno/

^ Kazimierz Wyka, "Mickiewicz, Adam Bernard", Polski Słownik Biograficzny, vol. XX, 1975, p. 697.

^ Rüdiger Nern, Erich Sachße, Bert Wawrzinek. Die Dresdner Albertstadt. Dresden, 1994; Albertstadt – sämtliche Militärbauten in Dresden. Dresden, 1880

^ ab Air Force Historical Studies Office: HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 14–15 FEBRUARY 1945 BOMBINGS OF DRESDEN Archived 17 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. including a list of all bombings

^ Bergander, Götz. Dresden im Luftkrieg: Vorgeschichte-Zerstörung-Folgen, p. 251 ff. Verlag Böhlau 1994,

ISBN 3-412-10193-1

^ "Names of Jewish victims of National Socialism in Dresden between 1933 and 1945 | Stiftung Sächsische Gedenkstätten". en.stsg.de. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ "Dresden | Jewish Virtual Library". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ "Victims of the National Socialist judiciary | Gedenkstätte Münchner Platz Dresden | Stiftung Sächsische Gedenkstätten". en.stsg.de. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ Nichol, John. "Dresden WW2 bombing raids killed 25,000 people - but it WASN'T a war crime". Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/dresden-ww2-bombing-raids-killed-5159536

^ "BBC On This Day | 14 | 1945: On February 14, 316 USAAF (8th Air Force) B-17's dropped 294.3 tons of incendiaries and 487.7 tons of high explosives. On February 15, 211 B-17's dropped 465.6 tons of bombs on the city. Thousands of bombs destroy Dresden". BBC News. 14 February 1945. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

^ (RAF Bomber Command 60th Anniversary – Campaign Diary February 1945 Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.)

^ BBC: Up to 25,000 died in Dresden's WWII bombing – report, 18 March 2010

^ Addison, Paul and Crang, Jeremy A. (eds.). Firestorm: The Bombing of Dresden. Pimlico, 2006.

ISBN 1-84413-928-X. Chapter 9 p.194

^ "'I would have destroyed Dresden again': Bomber Harris was unrepentant over German city raids 30 years after the end of World War Two". Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ http://www.lettersofnote.com/2009/11/slaughterhouse-five.html

^ "On Dresden Anniversary, Massive Protest Against Neo-Nazi March | Germany | Deutsche Welle | 14.02.2009". Dw-world.de. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

^ "Geh Denken – Startseite". Geh-denken.de. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

^ Shoumatoff, Alex. "How 1,280 Artworks Stolen by the Nazis were Hidden in a Munich Apartment Until 2012". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2015-07-20.

^ Dresden Elbe Valley, UNESCO World Heritage Register. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

^ ab Dresden loses UNESCO world heritage status, Deutsche Welle, 25 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

^ ab Bridge takes Dresden off Unesco world heritage list, The Guardian, 25 June 2009. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

^ (in German) Weltkulturerbe: Unesco-Titel in Gefahr, Focus, 14 March 2007; accessed 15 May 2007

^ Dresden is deleted from UNESCO's World Heritage List, UNESCO World Heritage Centre, 25 June 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

^ Dresden.de: Location, area, geographical data Archived 6 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ ab List of cities in Germany with more than 100,000 inhabitants

^ Dresden: "Dresden—a Green city". Archived from the original on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 30 March 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ "Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte".

^ "Bevölkerung und Haushalte 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 19 June 2018.

^ ab Dresden: Einwohnerzahl Archived 12 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Statistical office of the Free State of Saxony: Population and area of Saxony from 1815 on

^ State Office for statistics of Saxony. "Population of Saxon cities and communities". Retrieved 7 May 2010.

^ citypopulation.de quoting Federal Statistics Office. "Principal Agglomerations (of Germany)". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

^ Region Dresden. "Statistical data of the Dresden Region". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

^ ab "Dresden (Dresden, Saxony, Germany) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". citypopulation.de. Retrieved 2018-09-24.

^ Statistical office of the Free State of Saxony: Sachsen sind im Durchschnitt 45 Jahre alt – Dresdner am jüngsten, Hoyerswerdaer am ältesten (German)

^ "Gemeindeordnung für den Freistaat Sachsen (SächsGemO), §2". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Dresden.de: "City Council". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Dresden: "City Council". Archived from the original on 13 October 2006. Retrieved 29 June 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ "Dresden, City Council" (in German). City of Dresden. 25 May 2014. Missing or empty|url=(help)

^ "Dresden.de". Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 24 July 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ UNESCO: World Heritage Committee threatens to remove Dresden Elbe Valley (Germany) from World Heritage List

^ Dresden: "Saleof the WOBA Dresden GmbH". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2007.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Kirschbaum, Erik (16 December 2014). "Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamisation of the West quickly gathering support in Germany". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

^ "Städtepartnerschaften" (in German). Landeshauptstadt Dresden, Büro der Oberbürgermeisterin. Archived from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

^ Griffin, Mary (2 August 2011). "Coventry's twin towns". Coventry Telegraph. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

^ "Coventry - Twin towns and cities". Coventry City Council. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-13.

^ "Skopje - Twin towns & Sister cities". Official portal of City of Skopje. Grad Skopje - 2006 - 2013, www.skopje.gov.mk. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 2013-11-04.

^ Staff. "Hamburg und seine Städtepartnerschaften (Hamburg sister cities)" (in German). Hamburg's official website [1]. Retrieved 2008-08-05. External link in|publisher=(help)

^ "Strasbourg, Twin City". Strasbourg.eu & Communauté Urbaine. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

^ Semperoper: History of the Sächsische Staatskapelle Archived 5 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Staatsoperette Dresden Archived 16 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Kreuzchor Archived 22 May 2016 at the Portuguese Web Archive

^ steffen wollmerstaedt. "Landesbühnen Sachsen l Dresden l Theater l Rathen l Zwinger l Sachsen". Dresden-theater.de. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

^ [2] Bunte Republik Neustadt

^ Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden: Museums Archived 19 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Deutsches Hygiene-Museum: Deutsches Hygiene-Museum – The Museum of Man Archived 2 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

^ State Museum of Prehistory Archived 3 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Festung Dresden

^ Dresdner Verein Brühlsche Terrasse Archived 22 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

^ [3]

^ [4]

^ "O Códice de Dresden". World Digital Library. 1200–1250. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

^ Dresden: Monument preservation Archived 29 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden: The History of the Royal Palace Archived 23 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden: History of the Zwinger and Semperbau Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Roman Catholic Diocese of Dresden-Meissen: Kathedrale Ss. Trinitatis in Dresden

^ Evangelisch-Lutherische Kreuzkirchgemeinde Dresden: History of the Church of the Holy Cross Archived 29 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Sportgemeinschaft Dynamo Dresden e. V. :: DFB - Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V." datencenter.dfb.de. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

^ Dresdener Rennverein 1890 e.V.

^ Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe: "Profile". Archived from the original on 28 January 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe: Gleise und Haltestellen

^ Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe: "CarGoTram". Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2006.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ "Funicular Railway | VVO Navigator - Your mobility portal for Dresden and the region". vvo-online.de. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

^ Sächsischer Landtag Archived 15 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ "Oberlandesgericht Dresden". Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

^ Bundesagentur für Arbeit: Data and time series of the German labour market Archived 12 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

^ State Office for Statistics of the Free State of Saxony: Regional GDPs of 2004

^ Technische Universität Dresden: Profile of the TU Dresden

^ press release to the 2006 matriculation Archived 7 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Palucca Hochschule für Tanz

^ "Annual Report" (PDF). Max Planck Society. 2014.

^ Fraunhofer Society: Institutes

^ IPF

^ IFW

^ "Übersicht Dresdner Gymnasien - www.arbeitsagentur.de". arbeitsagentur.de. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

^ "Impressum/Disclaimer - Schulträger Freistaat Sachsen". cms.sachsen. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

^ Official Dresden City Webpage Archived 3 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

^ Miller 2017, p. 341.

References

Dresden: Tuesday, 13 February 1945 by Frederick Taylor, 2005;

ISBN 0-7475-7084-1

Dresden and the Heavy Bombers: An RAF Navigator's Perspective by Frank Musgrove, 2005;

ISBN 1-84415-194-8

Return to Dresden by Maria Ritter, 2004;

ISBN 1-57806-596-8

Dresden: Heute/Today by Dieter Zumpe, 2003;

ISBN 3-7913-2860-3

Destruction of Dresden by David Irving, 1972;

ISBN 0-345-23032-9

Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut, 1970;

ISBN 0-586-03328-9

Disguised Visibilities: Dresden by Mark Jarzombek in Memory and Architecture, Ed. By Eleni Bastea, (University of Mexico Press, 2004).

Miller, Michael (2017). Gauleiter Volume 2. California: R James Bender Publishing. ISBN 1-932970-32-0.

Preserve and Rebuild: Dresden during the Transformations of 1989–1990. Architecture, Citizens Initiatives and Local Identities by Victoria Knebel, 2007;

ISBN 978-3-631-55954-3

La tutela del patrimonio culturale in caso di conflitto Fabio Maniscalco (editor), 2002;

ISBN 88-87835-18-7

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dresden. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Dresden |

- Official homepage of the city

Dresden travel guide from Wikivoyage

Dresden travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official tourist office

- Homepage of the Dresdner Verkehrsbetriebe, the public transport provider

- Network maps of the public transport system

http://www.neumarkt-dresden.de/ Organisation for reconstruction of the Neumarkt