Fred Rogers

The Reverend Fred Rogers | |

|---|---|

Rogers on the set of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in the late 1960s | |

| Born | Fred McFeely Rogers (1928-03-20)March 20, 1928 Latrobe, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 2003(2003-02-27) (aged 74) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Other names | Mister Rogers |

| Alma mater | Rollins College Pittsburgh Theological Seminary |

| Occupation | Children's television presenter, actor, puppeteer, singer, composer, television producer, author, educator, Presbyterian minister |

| Years active | 1951–2001 |

| Spouse(s) | Joanne Byrd (m. 1952) |

| Children | 2 |

Pennsylvania Historical Marker | |

| Official name | Fred McFeely Rogers (1928–2003) |

| Type | Roadside |

| Designated | June 25, 2016 |

| Signature | |

Fred McFeely Rogers (March 20, 1928 – February 27, 2003) was an American television personality, musician, puppeteer, writer, producer, and Presbyterian minister. He was known as the creator, composer, producer, head writer, showrunner and host of the preschool television series Mister Rogers' Neighborhood (1968–2001). The show featured Rogers's kind, neighborly persona,[1] which nurtured his connection to the audience.[2] Rogers would end each program by telling his viewers, "You've made this day a special day, by just your being you. There's no person in the whole world like you; and I like you just the way you are."[3]

Trained and ordained as a minister, Rogers was displeased with the way television addressed children. He began to write and perform local Pittsburgh-area shows for youth. In 1968, Eastern Educational Television Network began nationwide distribution of Rogers's new show on WQED. Over the course of three decades, Rogers became a television icon of children's entertainment and education.[4]

Rogers advocated various public causes. In the Betamax case, the U.S. Supreme Court cited Rogers's prior testimony before a lower court in favor of fair-use television show recording (now called time shifting). Rogers also testified before a U.S. Senate committee to advocate for government funding of children's television.[5]

Rogers received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, 40 honorary degrees,[6] and a Peabody Award. He was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame and was recognized in two congressional resolutions. He was ranked number 35 of the TV Guide's Fifty Greatest TV Stars of All Time.[7]

Several buildings and artworks in Pennsylvania are dedicated to his memory, and the Smithsonian Institution displays one of his trademark sweaters as a "Treasure of American History". On June 25, 2016, the Fred Rogers Historical Marker was placed near Latrobe, Pennsylvania in his memory.[8]

Contents

1 Early life

2 Television career

2.1 Early work

2.2 Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

2.3 Other television work and legacy

2.4 Emmys for programming

3 Works

4 Advocacy

4.1 PBS funding

4.2 VCR

5 Personal life

6 Death and memorials

7 Awards and honors

7.1 Honorary degrees

7.2 Advertising

8 See also

9 References

10 Works cited

11 External links

Early life

Main Street, Latrobe, Pennsylvania, Rogers's birthplace.

Photo of Fred Rogers as a senior in high school.

Rogers was born on March 20, 1928, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania 40 miles (65 km) southeast of Pittsburgh, at 705 Main Street,[9] to James and Nancy Rogers. James was "a very successful businessman"[10] who was president of the McFeely Brick Company, one of Latrobe's largest businesses. Nancy's father, Fred Brooks McFeely, after whom Rogers was named, was an entrepreneur.[11] Nancy knitted sweaters for American soldiers from western Pennsylvania who were fighting in Europe and regularly volunteered at the Latrobe Hospital. Initially dreaming of becoming a doctor, she settled for a life of hospital volunteer work. Rogers grew up in a three-story brick mansion at 737 Weldon Street in Latrobe.[12][9] He had a sister, Elaine, who was adopted by the Rogerses when he was 11 years old.[12]

Rogers spent much of his childhood alone, playing with puppets and spending time with his grandfather. He learned how to play the piano when he was five years old.[6]

Rogers had a difficult childhood; he had a shy, introverted personality and was overweight. He was frequently homebound after suffering bouts of asthma.[10] He was bullied and taunted as a little boy for his weight, and was called "Fat Freddy."[13] According to Morgan Neville, director of the 2018 documentary Won't You Be My Neighbor?, Rogers had a "lonely childhood... I think he made friends with himself as much as he could. He had a ventriloquist dummy, he had [stuffed] animals, and he would create his own worlds in his childhood bedroom."[13]

Rogers attended Latrobe High School, where he overcame his shyness.[14] "It was tough for me at the beginning," Rogers told NPR's Terry Gross in 1984. "And then I made a couple friends who found out that the core of me was OK. And one of them was...the head of the football team."[15] Rogers served as president of the student council, was a member of the National Honor Society and was editor-in-chief of the school yearbook.[14] He attended Dartmouth College for one year before transferring to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida; he graduated in 1951 with a degree in music composition.[6]

Rogers graduated from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and was ordained a minister of the United Presbyterian Church in 1963.[16]

Television career

Early work

Rogers wanted to enter seminary after college, but instead chose to go into television, after encountering one at his parents' home in Latrobe in 1951. In an interview with CNN, Rogers said, "I went into television because I hated it so, and I thought there's some way of using this fabulous instrument to nurture those who would watch and listen".[18] After graduating in 1951, he worked at NBC in New York City, as floor director of Your Hit Parade, The Kate Smith Hour, and Gabby Hayes' children's show, and as an assistant producer of The Voice of Firestone.[19][20][21]

WQED headquarters in Pittsburgh

In 1953, Rogers returned to Pittsburgh to work as a program developer at public television station WQED. Josie Carey worked with Rogers to develop the children's show The Children's Corner, which Carey hosted. He worked off-camera with Carey to develop the puppets, characters, and music for show. Rogers used many of the puppet characters developed during this time, such as Daniel the Striped Tiger (named for WQED's station manager, Dorothy Daniel, who gave Rogers a tiger puppet before the show's premiere), King Friday XIII, Queen Sara Saturday (named for Rogers' wife),[22] X the Owl, Henrietta, and Lady Elaine, in his later work.[23][24] Children's television entertainer Ernie Coombs was an assistant puppeteer.[25]The Children's Hour won a Sylvania Award for best locally produced children's show in 1955 and was broadcast nationally on NBC.[26][27][28] While working on The Children's Hour, Rogers attended Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1963. He also attended the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Child Development,[29][28] when he began working with child psychologist Margaret McFarland, who according to Rogers biographer Maxwell King, became his "key advisor and collaborator" and his "child-education guru".[30] Much of Rogers' "thinking about and appreciation for children was shaped and informed" by McFarland.[29] She was his consultant for most of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood's scripts and songs for 30 years.[30]

In 1963, CBC in Toronto contracted Rogers to develop and host the 15-minute black-and-white children's program Misterogers; it lasted from 1963-1967.[25][31] It was the first time Rogers appeared on camera. Head of CBC's children programming Fred Rainsberry insisted on it, telling Rogers, "Fred, I've seen you talk with kids. Let's put you yourself on the air."[32] Coombs joined Rogers in Toronto as an assistant puppeteer.[25] Rogers also worked with Coombs on the children's show Butternut Square from 1964–1967. Rogers acquired the rights to Misterogers in 1967 and returned to Pittsburgh with his wife, his two young sons, and the sets he developed at the CBC back with him, despite his potentially promising career with the CBC and no job prospects in Pittsburgh.[33][34] (Coombs remained in Toronto, creating the long-running children's program Mr. Dressup, which ran from 1967 to 1996.)[35] Rogers' work for CBC "helped shape and develop the concept and style of his later program for the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the U.S."[36]

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood

Neighborhood Trolley from Mister Rogers' Neighborhood set at WQED studios in Pittsburgh.

Rogers screens the tape replay with Betty Aberlin and Johnny Costa in 1969.

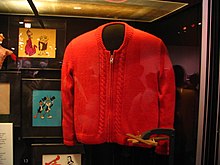

A sweater worn by Rogers, on display in the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of American History

Rogers and François Clemmons reprising their famous foot bath in 1993. The scene was a message of inclusion during an era of racial segregation.

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, a half-hour educational children's program starring Rogers, began airing in 1968 and ran for 895 episodes. It aired on National Educational Television, which later became The Public Broadcasting Service. The last set of new episodes was taped in December 2000 and began airing in August 2001. At its peak, in 1985, eight percent of US households tuned into the show.[6] According to musical director Johnny Costa, every episode of the program began with a pan of the Neighborhood, a miniature diorama model,[37] with his jazzy improvisations interwoven between the titles.[38] "Consisting of two sets: the inside set (Rogers' house) and the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, which included the castle" were filmed separately.[37]

Each episode had recurring motifs:

- Mister Rogers is seen coming home, singing his theme song "Won't You Be My Neighbor?", and changing into sneakers and a zippered cardigan sweater (he noted in an interview for Emmy TV that all of his sweaters were knitted by his mother).[39]

- In a typical episode, Rogers might have an earnest conversation with his television audience, interact with live guests, take a field trip to such places as a bakery or a music store, or watch a short film.[40]

- Typical video subjects included demonstrations of how mechanical objects work, such as bulldozers, or how things are manufactured, such as crayons.[41]

- Each episode included a trip to Rogers' "Neighborhood of Make-Believe" featuring a trolley with its own chiming theme song, a castle, and the kingdom's citizens, including King Friday XIII. The subjects discussed in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe often allowed further development of themes discussed in Mister Rogers' "real" neighborhood.[42]

- Mister Rogers often fed his aquarium fish during episodes. Rogers would always vocally announce to his audience he was feeding them because he received a letter from a young blind girl who wanted to know each time he did this.[43][44]

- Typically, each week's episode explored a major theme, such as going to school for the first time.

- At the outset, most episodes ended with a song entitled "Tomorrow", and Friday episodes looked forward to the week ahead with an adapted version of "It's Such a Good Feeling". In later seasons, all episodes ended with "Feeling".[45]

Visually, the presentation of the show was very simple, and it did not feature the animation or fast pace of other children's shows, which Rogers thought of as "bombardment".[46]

Rogers use of time on his show was a radical departure from other children's programming. Mister Rogers' Neighborhood was unhurried.[47]

Rogers also believed in not acting out a different persona on camera compared to how he acted off camera, stating that "One of the greatest gifts you can give anybody is the gift of your honest self. I also believe that kids can spot a phony a mile away."[48] Rogers composed almost all of the music on the program.[49][50] Rogers wrote over 289 songs over the course of the show.[49] Through his music, he wanted to teach children to love themselves and others, and he addressed common childhood fears with comforting songs and skits. For example, one of his famous songs explains how a child cannot be sucked down the bathtub drain as he or she will not fit.[51] He once took a trip to the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh to show children that a hospital is not a place to fear.[52]

Rogers frequently tackled complex social issues on his program including the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, racism and divorce.[53] On one notable episode, Rogers soaked his feet alongside Officer Clemmons (François Clemmons), who was African-American, in a kiddie pool on a hot day. The scene was a subtle symbolic message of inclusion during a time when racial segregation in the United States was widespread.[54]

In addition, Rogers championed children with disabilities on the show.[55] In a 1981 segment aired in Season 11, Episode 4, Rogers met a young quadriplegic boy, Jeff Erlanger, who showed how his electric wheelchair worked and explained why he needed it. Erlanger and Rogers both sang a duet of the song "It's You I Like." Before the taping, Erlanger had long been a fan of the program, and his parents wrote a letter to Rogers requesting they meet.[55] Years later, when Rogers was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1999, Erlanger was a surprise guest to introduce Rogers. Rogers "leaped" out of his seat and straight onto the stage when Erlanger appeared.[56][57]

Rogers based the show on his Christian values,[58] but never explicitly mentioned his faith on the show. "He wasn't doing that to hide his Christian identity," Junlei Li, co-director of the Fred Rogers Center, explained. "I think Fred was very adamant that he didn't want any viewer — child or adult — to feel excluded from the neighborhood."[59]

During the Gulf War (1990–91), he assured his audience that all children in the neighborhood would be well cared for and asked parents to promise to take care of their children.[60]

Other television work and legacy

In 1978, while on hiatus from taping new Neighborhood episodes, Rogers hosted an interview program for adults on PBS called Old Friends...New Friends.[61] On the show, Rogers interviewed "actors, sports stars, politicians, and poets." The show was short-lived, lasting only 20 episodes.[62]

In 1994, Rogers created a one-time special for PBS called Fred Rogers' Heroes, which consisted of documentary portraits of four persons whose work helped make their communities better. Rogers, uncharacteristically dressed in a suit and tie, hosted the show in wraparound segments that did not use the "Neighborhood" set.[63]

The only time Rogers appeared on television as someone other than himself was in 1996 when he played a preacher on one episode of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman.[6]

In the mid-1980s, the Burger King fast-food chain lampooned Rogers' image with an actor called "Mr. Rodney", imitating Rogers' television character.[64] Rogers found the character's pitching fast food as confusing to children, and called a press conference in which he stated that he did not endorse the company's use of his character or likeness. Rogers made no commercial endorsements during his career, though, over the years, he acted as a pitchman for several non-profit organizations dedicated to learning. The chain publicly apologized for the faux pas and pulled the ads.[65] In contrast, Fred Rogers found Eddie Murphy's parody of his show on Saturday Night Live, "Mister Robinson's Neighborhood," amusing and affectionate.[66] Rogers visited the Saturday Night Live studios in 1982. According to David Newell, "Fred knocked on Eddie's dressing room door. When Eddie opened it, he took a step back, surprised, then got a big smile on his face and said 'The REAL Mister Rogers' and hugged Fred."[67]

Rogers voice-acted himself on the "Arthur Meets Mister Rogers" segment of the PBS Kids series Arthur.[68]

In 1998, Rogers appeared as himself in an episode of Candid Camera as the victim of one of the show's pranks. The show's staff tried to sell him on a hotel room with no television. Rogers quickly caught on to the fact that he was being filmed for the show and surprised the show's producers by telling them he did not really need a television. Rogers was amused by his appearance on the show and by host Peter Funt's immediate recognition of him.[69]

.mw-parser-output .quotebox{background-color:#F9F9F9;border:1px solid #aaa;box-sizing:border-box;padding:10px;font-size:88%;max-width:100%}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft{margin:0.5em 1.4em 0.8em 0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright{margin:0.5em 0 0.8em 1.4em}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.centered{margin:0.5em auto 0.8em auto}.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatleft p,.mw-parser-output .quotebox.floatright p{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-title{background-color:#F9F9F9;text-align:center;font-size:larger;font-weight:bold}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:before{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" “ ";vertical-align:-45%;line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox-quote.quoted:after{font-family:"Times New Roman",serif;font-weight:bold;font-size:large;color:gray;content:" ” ";line-height:0}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .left-aligned{text-align:left}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .right-aligned{text-align:right}.mw-parser-output .quotebox .center-aligned{text-align:center}.mw-parser-output .quotebox cite{display:block;font-style:normal}@media screen and (max-width:360px){.mw-parser-output .quotebox{min-width:100%;margin:0 0 0.8em!important;float:none!important}}

—Rogers[70]

After the September 11 terrorist attacks, Rogers taped public service announcements for parents about how to discuss tragic world news events with their children.[71]

"We at Family Communications have discovered that when children bring up something frightening, it's helpful right away to ask them what they know about it," Rogers said. "Probably what children need to hear most from us adults is that they can talk with us about anything, and that we will do all we can to keep them safe in any scary time."[71]

In 2012, following the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, as people grappled with the gravity of the situation, a Rogers quote went viral on social media, advising people during troubling times to "look for the helpers."[71] On NBC's Meet the Press program, host David Gregory read the Rogers' quote on the air and added, "May God give you strength and at least you can know there is a country full of helpers here to catch you when you feel like falling."[71]

The quote continues to circulate widely following tragic news events.[72]

Emmys for programming

Mister Rogers' Neighborhood won four Emmy Awards, and Rogers himself was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 1997 Daytime Emmy Awards,[73] as described by Esquire's Tom Junod:

Mister Rogers went onstage to accept the award—and there, in front of all the soap opera stars and talk show sinceratrons, in front of all the jutting man-tanned jaws and jutting saltwater bosoms, he made his small bow and said into the microphone, "All of us have special ones who have loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, ten seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are. Ten seconds of silence." And then he lifted his wrist, looked at the audience, looked at his watch, and said, "I'll watch the time." There was, at first, a small whoop from the crowd, a giddy, strangled hiccup of laughter, as people realized that he wasn't kidding, that Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch, but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected them to do what he asked. And so they did. One second, two seconds, three seconds—and now the jaws clenched, and the bosoms heaved, and the mascara ran, and the tears fell upon the beglittered gathering like rain leaking down a crystal chandelier. And Mister Rogers finally looked up from his watch and said softly, "May God be with you" to all his vanquished children.[74][75]

Works

Rogers wrote many of the songs that were used on his television program, and wrote more than 36 books, including:

Mister Rogers Talks with Parents (1983)- Eight New Experiences titles:

- Moving

- Going to the Doctor

- Going to the Hospital

- Going to Day Care

- Going to the Potty

- Making Friends

- The New Baby

- When a Pet Dies

You Are Special: Words of Wisdom from America's Most Beloved Neighbor (1994)

Published Posthumously

The World According to Mister Rogers: Important Things to Remember (2003)

Life's Journeys According to Mister Rogers: Things to Remember Along the Way (2005)

Many Ways to Say I Love You: Wisdom for Parents and Children from Mister Rogers (2006)

Advocacy

Play media

Play mediaRogers speaks to Congress in 1969 in support of PBS.

PBS funding

In 1969, Rogers appeared before the United States Senate Subcommittee on Communications.[5] His goal was to support funding for PBS and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, in response to proposed budget cuts.[76] In about six minutes of testimony, Rogers spoke of the need for social and emotional education for children. He argued that alternative television programming like his Neighborhood helped encourage children to become happy and productive citizens, sometimes opposing less positive messages in commercial media and in popular culture. He recited the lyrics to one of his songs.[77]

The chairman of the subcommittee, John O. Pastore, was not familiar with Rogers' work and was sometimes described as impatient.[78] However, he reported that the testimony had given him goosebumps, and declared, "I think it's wonderful. Looks like you just earned the $20 million." The subsequent congressional appropriation, for 1971, increased PBS funding from $9 million to $22 million.[79]

VCR

During the controversy surrounding the introduction of the household VCR, Rogers was involved in supporting VCR manufacturers in court. His 1979 testimony, in the case Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., noted that he did not object to home recordings of his television programs by families in order to watch them together at a later time.[80] His testimony contrasted with the views of others in the television industry who objected to home recording or believed that VCRs should be taxed or regulated.[81][82]

When the case reached the Supreme Court in 1983, the majority decision considered the testimony of Rogers when it held that the Betamax video recorder did not infringe copyright.[83] The court stated that his views were a notable piece of evidence "that many [television] producers are willing to allow private time-shifting to continue" and even quoted his testimony in a footnote:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

Some public stations, as well as commercial stations, program the Neighborhood at hours when some children cannot use it ... I have always felt that with the advent of all of this new technology that allows people to tape the Neighborhood off-the-air, and I'm speaking for the Neighborhood because that's what I produce, that they then become much more active in the programming of their family's television life. Very frankly, I am opposed to people being programmed by others. My whole approach in broadcasting has always been "You are an important person just the way you are. You can make healthy decisions." Maybe I'm going on too long, but I just feel that anything that allows a person to be more active in the control of his or her life, in a healthy way, is important.[84]

Personal life

Rogers met Sara Joanne Byrd (called "Joanne") from Jacksonville, Florida, while he attended Rollins College. They were married in 1952 and remained married until his death in 2003. They had two sons, James and John.[85][86] According to biographer Maxwell King, close associates said that Rogers was "absolutely faithful to his marriage vows."[58]

Also according to King, in an interview with Rogers' friend William Hirsch, Rogers said that if sexuality was measured on a scale, then: "Well, you know, I must be right smack in the middle. Because I have found women attractive, and I have found men attractive."[58]

Rogers became a vegetarian in the 1970s, saying he couldn't eat anything that had a mother. He became a co-owner of Vegetarian Times in the 1980s and said in one issue "I love tofu burgers and beets".[87][88]

Though he largely avoided politics, Rogers was a lifelong Republican.[89][90] In reference to Donald Trump, his widow Joanne has stated that "his values are very, very different from Fred’s values - almost completely opposite." According to her, if Rogers were alive, "he might have to" speak up against modern political leaders whose values he differed from.[91]

Death and memorials

The Fred Rogers Memorial Statue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Created by Robert Berks, and opened to the public on November 5, 2009.

Rogers was diagnosed with stomach cancer in December 2002, and underwent surgery in January 2003.[92] A week earlier, he had served as grand marshal of the Tournament of Roses Parade, with Art Linkletter and Bill Cosby.[93]

Rogers died on the morning of February 27, 2003, at his home with his wife by his side,[94] less than a month before he would have turned 75. His death was such a significant event in Pittsburgh that most of the front page of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published the next day and an entire section of the paper devoted its coverage to him.[95] The Reverend William P. Barker presided over a public memorial in Pittsburgh. More than 2,700 people attended the memorial at Heinz Hall, including former Good Morning America host David Hartman; Teresa Heinz Kerry; philanthropist Elsie Hillman; PBS President Pat Mitchell; Arthur creator Marc Brown; and Eric Carle, the author-illustrator of The Very Hungry Caterpillar.[96] Speakers remembered Rogers's love of children, devotion to his religion, enthusiasm for music, and quirks. Teresa Heinz Kerry said of Rogers, "He never condescended, just invited us into his conversation. He spoke to us as the people we were, not as the people others wished we were."[97]

Rogers is interred at Unity Cemetery in Latrobe.[98]

At the 2003 Daytime Emmy Awards, host Wayne Brady and some of the cast of Sesame Street, including Big Bird, Elmo, Grover, Zoe, and Rosita, paid tribute to Rogers by singing a medley of some of his most popular songs, including "Won't You Be My Neighbor", "It's You I Like", "Everybody's Fancy", "Many Ways to Say I Love You", and "It's Such a Good Feeling".[99] Once they finished, a small clip of Rogers accepting an Emmy was played, which led the audience to give a standing ovation.[100]

In January 2018, it was announced that Tom Hanks would portray Rogers in an upcoming biographical film titled A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood directed by Marielle Heller.[101] That same year, the documentary film Won't You Be My Neighbor? based on the life and legacy of Rogers, was released to critical acclaim and became the highest-grossing biographical documentary film of all time.[102]

Awards and honors

Rogers being presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush in the East Room of the White House on July 9, 2002

On New Year's Day 2004, Michael Keaton, who had been a stagehand on Mister Rogers' Neighborhood before becoming an actor, hosted the PBS TV special Fred Rogers: America's Favorite Neighbor. It was released on DVD on September 28 that year. In 2008, to mark what would have been his 80th birthday, Rogers' production company sponsored several events to memorialize him, including "Won't You Wear a Sweater Day", during which fans and neighbors were asked to wear their favorite sweaters in celebration.[103] The event takes place annually on his birth date, March 20.[104]

Rogers received the Ralph Lowell Award in 1975.[105] In 1987, he was initiated as an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia Fraternity, the national fraternity for men of music.[106] The television industry honored Rogers with a George Foster Peabody Award "in recognition of 25 years of beautiful days in the neighborhood" in 1992;[107] previously, he had shared a Peabody award for Mister Rogers' Neighborhood in 1968. Rogers was a National Patron of Delta Omicron, an international professional music fraternity.[108] He was inducted into the Television Hall of Fame in 1999.[109] One of Rogers' iconic sweaters was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution, which displays it as a "Treasure of American History".[110] In 2002, Rogers received the PNC Commonwealth Award in Mass Communications.[111]

In 1991, the Pittsburgh Penguins named Rogers as their celebrity captain, as part of a celebration of the National Hockey League's 75th anniversary,[112] based on his connections to Pennsylvania and Pittsburgh. Card No. 297 from the 1992 NHL Pro Set Platinum collection commemorated the event, making Fred one of only twelve celebrity captains to be chosen for a sports card.[113]

George W. Bush awarded Rogers the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002 for his contributions to children's education, saying that "Fred Rogers has proven that television can soothe the soul and nurture the spirit and teach the very young". A year later, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed Resolution 16 to commemorate the life of Fred Rogers.[2] It read, in part, "Through his spirituality and placid nature, Mr. Rogers was able to reach out to our nation's children and encourage each of them to understand the important role they play in their communities and as part of their families. More importantly, he did not shy away from dealing with difficult issues of death and divorce but rather encouraged children to express their emotions in a healthy, constructive manner, often providing a simple answer to life's hardships." Following Rogers' death, the U.S. House of Representatives in 2003 unanimously passed Resolution 111 honoring Rogers for "his legendary service to the improvement of the lives of children, his steadfast commitment to demonstrating the power of compassion, and his dedication to spreading kindness through example."[114]

The same year, the Presbyterian Church approved an overture "to observe a memorial time for the Reverend Fred M. Rogers" at its General Assembly.[115] The rationale for the recognition of Rogers reads, "The Reverend Fred Rogers, a member of the Presbytery of Pittsburgh, as host of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood since 1968, had a profound effect on the lives of millions of people across the country through his ministry to children and families. Mister Rogers promoted and supported Christian values in the public media with his demonstration of unconditional love. His ability to communicate with children and to help them understand and deal with difficult questions in their lives will be greatly missed."[116]

In 2003, the asteroid 26858 Misterrogers was named after Rogers by the International Astronomical Union in an announcement at the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh.[117] The science center worked with Rogers' Family Communications, Inc. to produce a planetarium show for preschoolers called "The Sky Above Mister Rogers' Neighborhood", which plays at planetariums across the United States.[118]

Several buildings, monuments, and works of art are dedicated to Rogers' memory, including a mural sponsored by the Pittsburgh-based Sprout Fund in 2006, "Interpretations of Oakland," by John Laidacker that featured Mr. Rogers.[119]Saint Vincent College in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, completed construction of The Fred M. Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children's Media in 2008.[120] The Fred Rogers Memorial Statue on the North Shore near Heinz Field in Pittsburgh[121] was created by Robert Berks and dedicated in 2009.[122] The statue was placed in front of the surviving footing of the Manchester Bridge, which was cleaned and carved out in order to place the statue there.

In 2015, players of the Altoona Curve, a Double-A affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates, honored Rogers by wearing special commemorative jerseys that featured a printed facsimile of his classic cardigan and tie ensemble. After the game the jerseys were auctioned off with the proceeds going to the local PBS station, WPSU-TV.[123]

On March 6, 2018, a primetime special commemorating the 50th anniversary of the series aired on PBS, hosted by actor Michael Keaton.[124] The hour-long special also features interviews by musician Yo-Yo Ma, musician Itzhak Perlman, actress Sarah Silverman, actress Whoopi Goldberg, actor John Lithgow, screenwriter Judd Apatow, actor David Newell, producer Ellen Doherty, and spouse Joanne Byrd Rogers, as well as clips of memorable moments from the show, such as Rogers visiting Koko the gorilla, Margaret Hamilton dressing up as The Wizard of Oz's Wicked Witch of the West, and Jeff Erlanger in his wheelchair singing "It's You I Like" with Rogers.[125]

Fred Rogers appeared on a commemorative US postage stamp in 2018. The stamp, showing him as Mister Rogers alongside King Friday XIII, was issued on March 23, 2018, in Pittsburgh.[126]

On September 21, 2018, Google Doodle honored him with a stop motion video of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.[127] At 90, his widow, Joanne Byrd Rogers, still lives in Pittsburgh, where she has honored her husband's memory by being an advocate for children and encouraging them to take on leadership roles.[128][129][130][131][132][133][134][135]

Honorary degrees

Thiel College, 1969[136]

Eastern Michigan University, 1973[137]

Saint Vincent College, 1973[137]

Christian Theological Seminary, 1973[137]

Rollins College, 1974[137]

Yale University, 1974[138]

University of Pittsburgh, 1976[137]

Carnegie Mellon University, 1976[137]

Lafayette College, 1977[137]

Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, 1978[137]

Waynesburg University, 1978[137]

Linfield College, 1982[137]

Slippery Rock State College, 1982[137]

Duquesne University, 1982[137]

Washington & Jefferson College,1984[137]

University of South Carolina, 1985[137]

Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 1985[137]

Bowling Green State University, 1987[139]

University of Connecticut, 1991[140]

Boston University, 1992[141]

West Virginia University, 1995[142]

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, 1998[143]

Rider University, 1999[144]

Marist College, 1999[145]

Marquette University, 2001[146]

Dartmouth College, 2002[147]

Seton Hill University, 2003 (posthumous)[148]

Union College, 2003 (posthumous)[149]

Roanoke College, 2003 (posthumous)[147]

Advertising

On October 23, 2018, during the first game of the 2018 World Series, Rogers' first television commercial aired for Google's Pixel 3 smartphone. In the ad, Rogers sings "Did You Know". This is the first time his voice or images have been used to advertise a product on television.[150]

See also

Won't You Be My Neighbor? – 2018 documentary film about Rogers

A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood – 2019 biographical film about Rogers

References

^ John Donvan (February 2, 2018). "Mr Rogers ... Cool Dude" – via YouTube..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Bill Text – 108th Congress (2003–2004) – S.CON.RES.16.ATS". THOMAS. Library of Congress. March 5, 2003. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ Jackson, K.M.; Emmanuel, S.M. (2016). Revisiting Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Essays on Lessons About Self and Community. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7864-7296-3. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

^ Sostek, Anya (November 6, 2009). "Mr. Rogers takes rightful place at riverside tribute". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved September 6, 2010.

^ ab Harris, Aisha (October 5, 2012). "Watch Mister Rogers Defend PBS In Front of the U.S. Senate". Slate Magazine. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ abcde DeFranceso, Joyce (April 2003). "Remembering Fred Rogers: A Life Well-Lived: A look back at Fred Rogers' life". Pittsburgh Magazine. Archived from the original on January 3, 2005. Retrieved January 17, 2019.

^ "Special Collectors' Issue: 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time". TV Guide (December 14–20, 1996). 1996.

^ "Fred McFeely Rogers Historical – Latrobe – PA – US – Historical Marker Project".

^ ab Harpaz, Beth J. (July 18, 2018). "Mister Rogers: 'Won't you be my neighbor?' fans can check out Fred Rogers Trail". Burlington Free Press. Associated Press. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ ab "Early Life". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ Woo, Elaine (February 28, 2003). "It's a Sad Day in This Neighborhood". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ ab King (2018), p. 19

^ ab "7 items that tell the story of Mister Rogers, America's favorite neighbor". EW.com. June 9, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

^ ab Comm, Joseph A. (2015). Legendary Locals of Latrobe. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4671-0184-4.

^ Gross (1984), event occurs at 4.27.

^ Jacobson, Lisa (11 February 2013). "Remembering Mr. Rogers". Presbyterian Historical Society. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

^ "Terry Gross and Fred Rogers". Fresh Air with Terry Gross. NPR. February 28, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2019. Show originally aired 1985

^ Schuster, Henry (27 February 2003). "Fred and me: An appreciation". CNN.com. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

^ Hendrickson, Paul (November 18, 1982). "In the Land of Make Believe, The Real Mister Rogers". Washington Post. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

^ Gross (1984), event occurs at 6.38.

^ "Highlights in the life and career of Fred Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 27, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

^ "Fred Rogers". Pioneers of Television. PBS.org. 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

^ "Early Years in Television". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Tiech, John (2012). Pittsburgh Film History: On Set in the Steel City. Charleston, North Carolina: The History Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-60949-709-5.

^ abc Broughton, Irv (1986). Producers on Producing: The Making of Film and Television. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7864-1207-5.

^ "Sunday on the Children's Corner, Revisited". Presbyterian Historical Society. February 15, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Schultz, Mike. "Sylvania Award". uv201.com. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

^ ab "Fred Rogers Biography". Fred Rogers Productions. 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ ab Flecker, Sally Ann (Winter 2014). "When Fred Met Margaret: Fred Rogers' Mentor". Pitt Med. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ ab >King, p. 126

^ King (2018), p. 145

^ Roberts, Soraya (June 26, 2018). "The Fred Rogers We Know". Hazlitt Magazine. Penguin Random House. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ Matheson, Sue (2016). "Good Neighbors, Moral Philosophy and the Masculine Ideal". In Merlock Jackson, Sandra; Emmanuel, Steven M. Revisiting Mister Rogers' Neighborhood: Essays on Lessons about Self and Community. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Publishers. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-4766-2341-2.

^ King, p. 150

^ "How Mr. Rogers and Mr. Dressup's road trip from Pittsburgh to Toronto changed children's television forever". National Post. July 11, 2018. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and Beyond". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ ab "Filming Mister Rogers' Neighborhood". Johnny Costa Pittsburgh's Legendary Jazz Pianist. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ Hart, Ron (February 19, 1968). "The Music of Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and Johnny Costa". JazzTimes. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "Fred Rogers". Television Academy Interviews. January 1, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

^ "DPTV celebrates 50th anniversary of 'Mr. Rogers'". Detroit News. February 23, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "100 Billionth Crayola Crayon". Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning & Children's Media. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

^ Collins, M.; Kimmel, M.M. (1997). Mister Rogers Neighborhood: Children Television And Fred Rogers. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-8008-7. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ Rogers, F. (1996). Dear Mr. Rogers, Does It Ever Rain in Your Neighborhood?: Letters to Mr. Rogers. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-16169-2. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "WATCH: This Is Why We Will Always Love Mr. Rogers". HuffPost. April 10, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood Credit Videos". Retro Junk. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ WETA (February 27, 2018). "Mister Rogers Comes to Washington". Boundary Stones: WETA's Washington DC History Blog. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Kagan, Oleg (June 30, 2018). "What Mr. Roger's Neighborhood and Libraries Have in Common". Medium. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Owen, Rob (November 12, 2000). "There goes the Neighborhood: Mister Rogers will make last episodes of show in December". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette Magazine. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

^ ab "'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' at 50: Collaborators & Children's Singers Talk About His Musical Impact". Billboard. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "The Music of Mister Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. February 19, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "He Was Not Afraid Of The Dark". TIME.com. March 3, 2003. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "WOUB-HD to Air 'Mr. Rogers: It's You I Like' March 6". WOUB Digital. March 2, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ Meek, Tom (June 5, 2018). "'Won't You Be My Neighbor?' Frames Mr. Rogers As A Man On A Mission". WBUR. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ Blickley, Leigh (June 8, 2018). "The Gay 'Ghetto Boy' Who Bonded With Mister Rogers And Changed The Neighborhood". HuffPost. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ ab "How 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' Championed Children With Disabilities". Guideposts. October 15, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "Obituary: Jeffrey Erlanger / Quadriplegic who endeared himself to Mister Rogers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. June 14, 2007. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "Remembering Mr. Rogers, a True-Life 'Helper' When the World Still Needs One". EW.com. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

^ abc Maxwell King (4 September 2018). The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers. ABRAMS. pp. 208, 379. ISBN 978-1-68335-349-2.

^ "The surprising success - and faith - of Mister Rogers and 'Won't You Be My Neighbor?'". The Salt Lake Tribune. July 13, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

^ "PBS Public Service Announcement with mister rogers : NeighborhoodVideo : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Internet Archive. October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ "Fred Rogers Moves into a New Neighborhood—and So Does His Rebellious Son". PEOPLE.com. May 15, 1978. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ Liebman, Lisa (June 8, 2018). "11 Delightful Things We Learn About Mr. Rogers in Won't You Be My Neighbor?". Vulture. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ Williams, Scott (September 2, 1994). "'Mr. Rogers' Heroes' Looks at Who's Helping America's Children". AP NEWS. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ Edwards, Joe (May 21, 1984). "Burger King ad strategy pushes unit volumes near $1M". Nation's Restaurant News. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2009.

^ Dougherty, Philip (May 10, 1984). ADVERTISING; Thompson Withdraws An Ad for Burger King, The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

^ "An Unforgettable Neighbor". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. February 27, 2003. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "The Fred Rogers Company". Fred Rogers Productions. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

^ Fred Rogers – Voice Actor Profile at Voice Chasers. Retrieved October 19, 2012

^ "A Heartwarming Candid Camera Clip of an Unruffled Mister Rogers Being Told His Room Has No TV". Laughing Squid. March 19, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ "Tragic Events". Parent Resources. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

^ abcd "Mr. Rogers' words of comfort revived in wake of tragedy". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. December 18, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ "Why Mister Rogers' Plea To 'Look For The Helpers' Still Resonates Today". HuffPost. June 8, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

^ Video on YouTube

^ Junod, Tom (November 1998). "Can You Say ... 'Hero'?". Esquire. Archived from the original on March 1, 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Fred Rogers Acceptance Speech – 1997" on YouTube Official Emmys channel. March 26, 2008. Retrieved Mar 10, 2011.

^ Strachan, Maxwell (March 16, 2017). "The Best Argument For Saving Public Media Was Made By Mr. Rogers In 1969". HuffPost. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "Mister Rogers defending PBS to the US Senate". June 29, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2016 – via YouTube.

^ Bradberry, Travis (September 25, 2014). "How Emotional Intelligence Landed Mr. Rogers $20 Million". Forbes. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "Fred Rogers Beyond the Neighborhood: Senate Committee Hearing". Fred Rogers Center. 1969. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

^ "SONY CORP. OF AMER. v. UNIVERSAL CITY STUDIOS, INC., 464 U.S. 417 (1984)". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Shea, Christopher (January 10, 2012). "Mr. Rogers and the VCR". WSJ. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "How Mister Rogers Saved the VCR". Mental Floss. June 7, 2018. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ Madrigal, Alexis C. (January 10, 2012). "The Court Case That Almost Made It Illegal to Tape TV Shows". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984)". Supreme Court of the United States of America. 1984. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ Dawn, Randee (12 June 2018). "Fred Rogers' widow reveals the way he proposed marriage — and it's so sweet". Today.com. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

^ King (2018), p. 54

^ King (2018), p. 9

^ Obis, Paul (November 1983). "Fred Rogers: America's Favorite Neighbor". Vegetarian Times. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

^ [1]"Fred Rogers was a lifelong Republican..."

^ [2]"An unusual tidbit of information was revealed in this documentary: Mr. Rogers was a “life-long Republican.” It’s been confirmed by credible sources, including his wife, Joanne."

^ https://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/mister-rogers-wife-husband-speak-political-leadership-today/story?id=55730892

^ "Fred Rogers". Biography.com. 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

^ "Grand Marshal Slide Show Main". Tournament of Roses. 2004. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

^ Owen, Rob; Barbara Vancheri (February 28, 2003). "Fred Rogers dies at 74". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Fred Rogers dies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – via Google News Archive Search.

^ Vancheri, Barbara; Owen, Rob (May 4, 2003). "Pittsburgh bids farewell to Fred Rogers with moving public tribute". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ Vancheri, Barbara (May 4, 2003). Pittsburgh bids farewell to Fred Rogers with moving public tribute, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

^ King, M. (2018). The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers. ABRAMS. p. 443. ISBN 978-1-68335-349-2. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ Publicity, PBS (May 17, 2003). "PBS Scores Two Major Wins at Daytime Emmys Televised Ceremony". PBS Scores Two Major Wins at Daytime Emmys Televised Ceremony | PBS About. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

^ 30th Daytime Emmy Awards (Television). New York, NY: ABC. May 16, 2003.

^ "Soulful, Inspiring Mister Rogers Movie Trailer Just Might Make You Cry". Vanity Fair. March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

^ "Won't You Be My Neighborhood Is the Top Grossing Biodoc of All Time". The Hollywood Reporter. July 27, 2018.

^ "Won't You Wear a SweaterByrd?". Rollins News Center. Rollins College. March 21, 2008. Archived from the original on June 9, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Wear a sweater, honor Mr. Rogers". Today. February 27, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2016.

^ Silva, P (July 20, 2015). "Ralph Lowell Award".

^ Faith Spicer, Cheri (May 2004). "Remembering Our Neighbor: His Lessons on Listening and Love" (PDF). The Sinfonian. sinfonia.org. pp. 19–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 29, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "George Foster Peabody Award Winners". University of Georgia, George Foster Peabody Award.

^ "National Patrons & Patronesses". Delta Omicron. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Hall of Fame". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

^ "NMAH – Treasures of American History – American Television (page 2 of 2)". National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "PNC Honors Six Achievers Who Enrich The World". PNC Financial Services Group - MediaRoom. April 20, 2002. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "Can you say ... captain?". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 65 (58). October 7, 1991. p. 1. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

^ "Mister Rogers' Hockey Card". Puck Junk. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

^ "Bill Text – 108th Congress (2003–2004) – H.RES.111.EH". THOMAS. Library of Congress. March 4, 2003. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

[dead link]

^ "Recommendations on Business before the 215th General Assembly". General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. 2003. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Minutes: 215th General Assembly (2003), Part I" Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Office of the General Assembly, Proceedings of the 215th General Assembly (2003) of the Presbyterian Church, p. 107. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

^ "IAU Minor Planet Center". IAU Minor Planet Center. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "'The Sky Above Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' coming to Delta". Midland Daily News. November 3, 2005. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

^ "2006 Sprout Public Art Mural Kickoff Event Schedule". thisishappening. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ "Fred M. Rogers Center". Saint Vincent College. 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

^ Sostek, Anya (November 5, 2009). "Sculpture of Fred Rogers unveiled on North Side". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

^ Butter, Bob (November 5, 2009). "World's First Sculpture of American Icon Fred Rogers Unveiled". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2009.

^ Maloy, Brendan (June 11, 2015). "Minor league team honors Mr. Rogers with cardigan uniforms". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

^ Hinckley, David (March 3, 2018). "Mister Rogers has become 'one of the coolest men on the planet'". Daily News. New York. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

^ Ryan, Patrick (February 2, 2015). "5 ways to celebrate 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' on its 50th anniversary". USA Today. Mclean, Virginia: Gannett Company. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

^ U.S. Postal Service Provides First-Day Date and Locations for 2018 First Quarter Stamp Issuances, US Postal Service news release, December 19, 2017

^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rd7X0NsOeRk

^ [3]

^ Dawn R. Fred Rogers' widow reveals the way he proposed marriage — and it's so sweet. Today. June 12, 2018 / 11:32 AM EDT

^ Schlageter W. Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh to honor Joanne Rogers with its 2016 Great Friend of Children Award. Children's Museum Pittsburgh. Accessed 10/28/2018

^ Kaufman A. Fred Rogers' family keeps the legacy of 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood' alive with a candid new documentary. Los Angeles Times, June 12, 2018, 3:00 AM

^ Lyons K. Joanne Rogers on Fred Rogers’ legacy and her Great Friend of Children Award. Current Features, Features. Next Pittsburgh. February 2, 2016. Accessed 10/28/2018

^ Niedospial L. The Sweet Story Behind Mister Rogers' Nearly 51-Year Marriage to Wife Joanne. MSN Lifestyle. PopSugar, 5/1/2018, Accessed 10/28/2018

^ Joanne Rogers (profile), Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra website, Accessed 10/28/2018

^ Sciullo M. Joanne Rogers embodies the life, love and spirit of husband Fred Rogers' legacy. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 11, 2018, 3:27 PM, Accessed 10/28/2018

^ Erdley, Debra. "Thiel College remembers Mister Rogers". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ abcdefghijklmno "Honorary Degrees Awarded to Fred Rogers".

^ "Music student pens Mister Rogers score". Yale Daily News. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Readers: Goodbye Mister Rogers". Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients - 1990s | Honorary Degrees". honorarydegree.uconn.edu. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients of the Past 25 Years" (PDF).

^ "W.V. UNIVERSITY TO HONOR A NEIGHBOR: MR. ROGERS". Deseret News. April 6, 1995. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Pa. Physician General, nearly 800 EU students receive degrees - Edinboro University". edinboro.edu. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Honorary Degree Recipients". Rider University. August 27, 2010. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Commencement; Fordham Class Hears Magician and Peacemaker". Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Fred Rogers". University Honors | Marquette University. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

^ ab "Academic Hood Quilt". The Fred Rogers Center. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

^ "Seton Hall Will Have Tribute to Rogers". Huron Daily Tribune. April 17, 2003. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ "Joanne Rogers accepts husband's 41st honorary degree". Union College News Archives. June 15, 2003. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

^ Pressman, Aaron (October 24, 2018). "Mister Rogers Stars in His First TV Commercial—For Google". Fortune. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

Works cited

- Gross, Terry (1984). "Terry Gross and Fred Rogers". Fresh Air. NPR.

- King, Maxwell (2018). The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers. Abrams Press.

ISBN 978-1-68335-349-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fred Rogers. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Fred Rogers |

Fred Rogers on IMDb

Fred Rogers at Find a Grave

- PBS Kids: Official Site

- The Fred M. Rogers Center

The Fred Rogers Company (formerly known as Family Communications)

Fred Rogers at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

"It's a Beautiful 50th Birthday for 'Mister Rogers' Neighborhood'". Fresh Air. NPR. February 19, 2018. 1984 interview with Fred Rogers.- The Music of Mister Rogers – Pittsburgh Music History

- Fred Rogers at Voice Chasers

Appearances on C-SPAN