Iniidae

| Iniidae Temporal range: Miocene-Holocene | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Amazon river dolphin at Duisburg Zoo. | |

| |

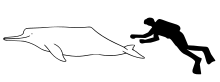

| Size compared to an average human | |

Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Superfamily: | Inioidea |

| Family: | Iniidae Gray, 1846 |

| Genera | |

see text | |

Iniidae is a family of river dolphins containing one living and four extinct genera.

Iniidae, also known as the Amazon River Dolphin or boto[1], can be found throughout the freshwater habitats of the Amazon rivers and Orinoco Basin[2]. The Amazon River Dolphin, genus Inia, is endemic to South America and the only extant genus of the family Iniidae.[3] Iniidae are highly morphologically different from marine dolphins, making them suited to their habitat[4]. Also, they display a high amount of sexual dimorphism, like color and size[1]. Seasonal movement between flooded plains and rivers is common, due to the variation of seasonal rain[5]. Very little is known about the South American River species, since there has not been much research on them.[1]

Contents

1 Morphology

2 Migration

3 Feeding

4 Sexual dimorphism

5 Reproduction

6 Speciation

7 Conservation

8 Taxonomy

9 References

10 External links

Morphology

The river basins were flooded by marine waters, creating a new brackish habitat that allowed marine mammals to move into the Amazon River Basins. During the Miocene era, the sea level began to recede, trapping the mammals within the continent.[4] The Iniidea have adapted morphology common to freshwater, riverine habitats[3] These adaptions include cervical vertebra that are not fused, allowing for a flexible neck. Also, their dorsal (back) fin are highly reduced or absent so they do not become entangled in vegetation from the flooded terrestrial plains. Large and wide, paddle-like, pectoral fins allow for maneuverability in small vegetated areas.[6] Other riverine adaption including a long rostrum, skull and jaw, and reduced orbits[7]. Iniidae have many characteristic common to their marine odontocete relatives. Their stomachs include a fore-stomach, singled chambered main stomach, and a pyloric stomach with connecting channels. Also, iniidae have lost their fur and lack true vocal cord.[8] They share the similar structure of the tympanic bulla and lung shape, the position of their diaphragm, and the position of the blowhole to the back of the head, with their marine ancestors.

The dentition of Iniidae dolphins is heterodont,[citation needed] having conical, small teeth. The teeth extend lingually in the back and in the front they have a small depression on the side of each. These mammals are carnivorous, finding prey by using echolocation.

Migration

Iniidae seasonally follow fish migration, also. In the drier, seasons they are restricted to the deeper channels and found along flooded meadows and forest, and also near tributaries. Along the main river are floodplain lakes. The number of river dolphins found here are seasonal, suggesting that the floodplains are favored. These floodplains are especially favored by females and the offspring that still rely on them for parental care. Since the water level fluctuates seasonally, no dolphin spends their entire life here. Also, the ratio of males to females in these lake systems is uneven. Females are more dominant in the floodplains, while males are congregated more in the rivers.[1]

Feeding

Iniidae feed during the day and night but are most actively feeding in the early morning and evening[9]. Fish were the only food for Inia to be recorded[10]. To find their food, biosonar is used. This short-range biosonar allows them to locate their prey in shallow water environments while helping them maneuver.[11]

Sexual dimorphism

Males are typically larger than the female river dolphins. Males are up to 16% longer and more than 50% heavier than their female partners, making them one of the most sexually dimorphic species of cetaceans. In general, male botos have a stronger hue of pink than females, while the pinkest dolphins are nearly all males.[1] Juvenille Botos are gray, since their base pigment is gray. The scar tissue in this genus is pink. For many adults, their skin is covered in scars. Females tend to be less lacerated then the males. A cobblestone scarring pattern on caudal and dorsal fins are only found in males. This most likely gives rise to the intense pink color. The male Inia dolphins are also known to use an object in their sexual display, suggesting that the visual color may play a role in mate selection. Larger body size and pink color are consequences of sexual selective pressure.[1]

Reproduction

Mating takes place from June to September, while the gestation period can last from 10 to 11 months. Species of Iniidae produce their offspring between May and July, to coincide with the dry season. With falling water levels fish are herded out of the floodplains, causing a high food availability.[6]

Breeding for Iniidae dolphins is seasonal and varies according to food availability and water levels. A single offspring is produced per season. The gestation period is approximately 11 months, and they can produce offspring every year and a half. The lactation period is long, and calves stay with mothers for a few years before becoming independent. The age of maturity is unknown but thought to be at a few years old. Mating systems of this family are unknown, but scientists do know that females take after the young and look to be the limiting factor, which suggests a polygynous system.

Speciation

There is a debate on the number of species within the genus Inia. The main debate is whether there are two or three species and whether they can be considered sub-species. I. geoffrensis, I. humboldtiana and I. boliviensi, according to certain scientist are considered three separate species, while many consider I.geoffrensis and I. boliviensi to be the only two.[2][12][5]. Martin in 2004 founded supporting evidence that genetic exchange between multiple sites of the Amazon, even ones hundreds of kilometers away is possible.

Conservation

Inia dolphins are threatened mainly by human populations in the country they can be found in. This includes incidental and even deliberate captures by fishers[2]. The deliberate capture of these dolphins is rare and illegal in Brazil. However, these types of activity have been reported in more northern areas of the country. Through interviewing of fishers, it appears that they are dislike, unwanted and in some cases hated by the fishers.[13]. Redlist has not yet classified this species, due to the lack of information on it.

Taxonomy

The family was described by John Edward Gray in 1846.[14]

Current classifications include a single living genera, Inia, with one to three[15] species and several subspecies. The family also includes three extinct genera described from fossils found in South America, Florida, Libya, and Italy.[14]

- Superfamily Inioidea

- Family Iniidae

- Genus †Goniodelphis

- G. hudsoni

- Genus Inia

Inia araguaiaensis - Araguaian river dolphin

Inia boliviensis - Bolivian river dolphin

Inia geoffrensis - Amazon river dolphin

I. g. geoffrensis - Amazonian river dolphin

I. g. humboldtiana - Humboldt River dolphin

- Genus †Isthminia

- †Isthminia panamensis

- †Isthminia panamensis

- Genus †Meherrinia

- Genus †Ischyrorhynchus (syn. Anisodelphis)

I. vanbenedeni (syn. Anisodelphis brevirostratus)

- Genus †Saurocetes (syn. Saurodelphis, Pontoplanodes)

S. argentinus (syn. Pontoplanodes obliquus)- S. gigas

- Genus †Goniodelphis

- Family Iniidae

References

^ abcdef Martin, A. R., & Silva, V. M. (2006). Sexual Dimorphism And Body Scarring In The Boto (Amazon River Dolphin) Inia Geoffrensis. Marine Mammal Science,22(1), 25–33. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00003.x

^ abc Gravena, Waleska, et al. "Looking to the past and the future: were the Madeira River rapids a geographical barrier to the boto (Cetacea: Iniidae)?." Conservation Genetics 15.3 (2014): 619–629.

^ ab Gutstien, Carolina (2014). "The Antiquity of Riverine Adaptations in Iniidae (Cetacea, Odontoceti) Documented by a Humerus from the Late Miocene of the Ituzaingo Formation, Argentina". The Anatomical Record. 297 (6). Retrieved 2018-04-01..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab Hamilton, Healy, et al. "Evolution of river dolphins." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 268.1466 (2001): 549-556.

^ ab Rice, Dale W. "Marine mammals of the world, systematics and distribution." Society for Marine Mammalogy Special Publication 4 (1998): 1-231.

^ ab Gomez-Salazar, C. (2011). Photo-Identification: A Reliable and Noninvasive Tool for Studying Pink River Dolphins (Inia geoffrensis). Aquatic Mammals,37(4), 472–485. doi:10.1578/am.37.4.2011.472

^ Pyenson, Nicholas D., et al. “Isthminia Panamensis, a New Fossil Inioid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the Evolution of 'River Dolphins' in the Americas.” PeerJ, PeerJ Inc., 1 Sept. 2015, peerj.com/articles/1227/.

^ Kaiya, Zhou. "Classification and phylogeny of the Superfamily Platanistoidea, with notes on evidence of the monophyly of the Cetacea." Sci. Rep. Whale Res. Inst 34 (1982): 93–108.

^ Gomez-Salazar, C. (2011). Photo-Identification: A Reliable and Noninvasive Tool for Studying Pink River Dolphins (Inia geoffrensis). Aquatic Mammals, 37(4), 472-485. doi:10.1578/am.37.4.2011.472

^ Layne, James N. "Observations on freshwater dolphins in the upper Amazon." Journal of Mammalogy 39.1 (1958): 1–22.

^ Ladegaard, Michael, et al. “Amazon River Dolphins (Inia Geoffrensis) Use a High-Frequency Short-Range Biosonar.” Journal of Experimental Biology, The Company of Biologists Ltd, 1 Oct. 2015, jeb.biologists.org/content/218/19/3091.

^ Ruiz-García, M., Banguera, E., & Cardenas, H. (2006). Morphological analysis of three Inia (Cetacea: Iniidae) populations from Colombia and Bolivia. Acta Theriologica, 51(4), 411–426. doi:10.1007/bf03195188

^ Luiz Cláudio Pinto De Sá Alves, et al. “Conflicts between River Dolphins (Cetacea: Odontoceti) and Fisheries in the Central Amazon: a Path toward Tragedy?” Zoologia (Curitiba), vol. 29, no. 5, 2012, pp. 420–429., doi:10.1590/s1984-46702012000500005.

^ ab The paleobiology Database

^ Hrbek, Tomas; Da Silva, Vera Maria Ferreira; Dutra, Nicole; Gravena, Waleska; Martin, Anthony R.; Farias, Izeni Pires (2014-01-22). Turvey, Samuel T., ed. "A New Species of River Dolphin from Brazil or: How Little Do We Know Our Biodiversity". PLOS ONE. 9: e83623. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083623. PMC 3898917. PMID 24465386.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iniidae. |

Wikispecies has information related to Iniidae |