Interpersonal communication

Poster promoting better interpersonal communications in the workplace, showing an angry man seated behind a desk and a cowering subordinate. (Work Projects Administration Poster Collection (Library of Congress).

Interpersonal communication is an exchange of information between two or more people.[1] It is also an area of study and research that seeks to understand how humans use verbal and nonverbal cues to accomplish a number of personal and relational goals.[1] Generally, interpersonal communication research has contributed to at least six distinct categories of inquiry: 1) how humans adjust and adapt their verbal communication and nonverbal communication during face-to-face communication, 2) the processes of message production, 3) how uncertainty influences our behavior and information-management strategies, 4) deceptive communication, 5) relational dialectics, and 6) social interaction that is mediated by technology.[2]

A large number of scholars collectively identify with and use the term interpersonal communication to describe their own work an Example is,Ezra Elioenai Addo a Ghanaian Scholar. These scholars, however, also recognize that there is considerable variety in how they and their colleagues conceptually and operationally define this area of study. In some regards, the construct of interpersonal communication is like the phenomena it represents- that is, it is dynamic and changing. Thus, attempts to identify exactly what interpersonal communication is or is not are often frustrating and fall short of consensus.[3] Additionally, many who research and theorize about interpersonal communication do so from across many different research paradigms and theoretical traditions.[4]

While there are many definitions available, interpersonal communication is often defined as the communication that takes place between people who are interdependent and have some knowledge of each other. Interpersonal communication includes what takes place between a son and his father, an employer and an employee, two sisters, a teacher and a student, two lovers, two friends, and so on. Although largely dyadic in nature, interpersonal communication is often extended to include small intimate groups such as the family. Interpersonal communication can take place in face-to-face settings, as well as through media platforms, such as social media.[5]

The study of interpersonal communication looks at a variety of elements that contribute to the interpersonal communication experience. Both quantitative/social scientific methods and qualitative methods are used to explore interpersonal communication. Additionally, a biological and physiological perspective on interpersonal communication is a growing field. Within the study of interpersonal communication, some of the concepts explored include the following: personality, knowledge structures and social interaction, language, nonverbal signals, emotion experience and expression, supportive communication, social networks and the life of relationships, influence, conflict, computer-mediated communication, interpersonal skills, interpersonal communication in the workplace, intercultural perspectives on interpersonal communication, escalation and de-escalation of romantic or platonic relationships, interpersonal communication and healthcare, family relationships, and communication across the life span.[3]

Contents

1 Role

2 Context

2.1 Interpreting Talk through the Uncertainty Reduction Theory

2.2 Situational milieu

2.3 Cultural and linguistic backgrounds

2.4 Developmental Progress (maturity)

3 Theories

3.1 Uncertainty reduction theory

3.2 Social exchange theory

3.3 Symbolic interaction

3.4 Relational dialectics theory

3.4.1 The three relational dialectics

3.4.2 Connectedness and separateness

3.4.3 Certainty and uncertainty

3.4.4 Openness and closedness

3.5 Coordinated management of meaning

3.6 Social penetration theory

3.7 Relational patterns of interaction theory

3.7.1 Ubiquitous communication

3.7.2 Expectations

3.7.3 Patterns of interaction

3.7.3.1 Symmetrical relationships

3.7.3.2 Complementary relationships

3.7.4 Relational control

3.7.5 Complementary exchanges

3.7.6 Symmetrical exchanges

3.8 Theory of intertype relationships

3.9 Identity management theory

3.9.1 Establishing identities

3.9.2 Cultural influence

3.9.3 Tensions within intercultural relationships

3.9.4 Relational stages of identity management

3.10 Communication privacy management theory

3.10.1 Boundaries

3.10.2 Co-ownership of information

3.10.3 Boundary turbulence

3.11 Cognitive dissonance theory

3.11.1 The selection process

3.11.2 Types of cognitive relationships

3.12 Attribution theory

3.12.1 Steps to the attribution process

3.12.2 Fundamental attribution error

3.12.3 Actor-observer bias

3.13 Expectancy violations theory

3.13.1 Arousal

3.13.2 Reward valence

3.13.3 Proxemics

3.13.4 Dyadic communication and Relationships

3.14 Pedagogical communication

3.15 Social networks

3.16 Hurt

3.17 Conflict

3.18 Technology and Interpersonal Communication Skills

4 See also

5 References

6 Further reading

Role

The role of interpersonal communication has been studied as a mediator for mass media effects. Since Katz and introduced their ‘filter hypothesis’, maintaining that personal communication mediates the influence of mass communication on individual voters, many studies have repeated this logic when combining personal and mass communication in effect studies on election campaigns (Schmitt-Beck, 2003). Although some research exists that examines the activities of social networking and the potential effects, both positive and negative, on its users, there is a gap in the empirical literature. Social networking relies on technology and is conducted over specific devices with no presence of face-to-face interaction, which results in an inability to access interpersonal behavior and signals to facilitate communication. (Drussel, 2012) As many positive advances we’ve seen come from the latest web innovations, can it be said that there are negative ones as well? Interpersonal communication is defined as what one uses with both spoken and written words as the basis to form and maintain personal relationships with others (Heil 2010). As technological advancements are made, the residual impact of social networking on society's young generation is of valuable importance to researchers in the social work field. Left unattended, the lack of skills to effectively communicate and resolve conflicts in person may negatively affect behavior and impair the ability to develop and maintain relationships. (Drussel,2012)

Technological side effects may not always be apparent to the individual user and, combined with millions of other users, may have large-scale implications. Therefore, each participant has a dual role—as an individual who may be affected by the social environment and as a participant who is interacting with others and co-constructing the same environment (Greenfield & Yan, 2006). Berson, Berson and Ferron (2002) believe that benefits of online interaction included learning relational skills, expressing thoughts and feelings in a healthy way, and practicing critical thinking skills. However, there are some problems with this because one important negative point of interpersonal communication through social network is that people who rely on social networking lose their ability to communicate with others face-to-face. On the other hand, positive and negative effects of using interpersonal communication vary and depends on individual point of view. In which case, it makes it challenging to give this question a specific answer.

Context

Understanding the context of the situation so you can better execute the task

An image depicting individuals understanding the context of the situation and taking the necessary precautions because of it.

Context generally refers to the environmental factors that influence the outcomes of communication. This includes the time and place as well as the background of the participants.[6] In any given environment/situation a conversation takes place in, many contexts may be interacting at the same time.[7] To have an in-depth understanding of the interpersonal interaction, the retrospective context and the emergent context must be examined and considered. The retrospective context is defined as everything that comes before a particular behavior that might help understand and interpret that behaviour. The emergent context is described as all events that come after the said behavior and which may also contribute to understanding the behaviour.[8] Context in regards to interpersonal communication refers to the establishment and control of formal and informal relationships.[9] Generally, the focus has been on "dyadic communication" meaning face to face mutual ideas between two individuals in health communication research with a focus on the patient and the provider.[9] Additionally, interest in the role of families, and occasionally among other key roles in the health care system are all factors on the context of interpersonal communication. When trying to understand the harmony and balance of the behaviour one should be aware of the tone rather than focusing solely on what is actually said in order to understand the other party's perspective. Regardless of how intimate the relationship, people communicate their perspectives and preferences by what is said in addition to their tone of voice, facial expressions, how welcoming they are, and so forth.[10] The language and messages in conversation can be ambiguous if taken at face value but in the English language, how something is said can more impact than the statement itself. Context dictates the structure and constituent view of the conversation and ultimately the relationship.

Interpreting Talk through the Uncertainty Reduction Theory

Understanding the distinctions and nuances of a situation provides clarity when looking to build on a developing relationship. Factors like gender, culture, personal interest and the environment play a role in understanding one’s perspective to communicate more effectively. If a negotiation or debate is transpiring, the recognition of these factors can also establish the boundaries of the discussion as well as the relationship itself. The concept of interpreting talk sets the foundation that allows individuals to interact in a safe space with knowledge that minimizes the potential of damaging a relationship. This is essential in platonic, romantic, family and professional relationships because they all are ongoing and integral to one’s overall satisfaction in life.

Principles from two theoretical studies help justify why individuals conduct themselves in a particular fashion while shedding light on how they go about it. One is the Uncertainty Reduction Theory, that argues people look to gain information about others, reducing uncertainty, with hopes of establishing healthy relationship where the benefits outweigh the costs [11] This theory was created by Charles Berger and Richard Calabrese to understand the communication process between strangers that connected to our expectations since people are naturally inquisitive, social beings.[12]

The studies of Uncertainty Reduction Theory evolved from only pertaining to the interaction of strangers and the expectations associated, if any, to the realization that it was evident in most forms of human communication.[13] It is human nature to want to belong to something bigger than yourself so it’s no coincidence that people subconsciously are looking to bond with others when given the opportunity, especially with your preferred sex. Therefore, after someone’s attention is captured in an initial greeting, people tend to look for subtle cues to see if the other party is willing to continue, often seen as being friendly and welcoming. Duck states the continuation of these initial interactions as “unfinished business” that will last until the relationship ceases.[14] On the contrary, rejection could lead to frustration that eventually could make your insecurities even worse. The theory states the three strategies people go about seeking information is: (1) Passive - observing them in their natural environment. (2) Interactive – directly communicating with the person. (3) Active - reaching out to others for the information and determining if the next step should be observing them passively or interactively communicating with them.[15] In the social media era we live, a study was done that revealed the passive strategy, is the most commonly used but the interactive strategy reduces the most uncertainty.[15] Information gained from these strategies not only reduces uncertainty but also increase the likelihood of predicting the others’ next course of action. The behavior associated with these strategies is known as “self-monitoring”, where people strategically manipulate how they present themselves due to the information they have received.[16]

As studies developed there have been other uncertainties related to oneself, their partner, and the relationship that stem from these behaviors. During self-uncertainty an individual’s insecurity makes one question and start trying to seek information about their own past behaviors and predict what they should act going forward. This can be independent or derived from partner-uncertainty, where people try to figure out what problems have occurred that justify the other individual’s behavior or feelings so they can be a better help to them. The last form is a combination of the two known as relationship uncertainty. This occurs when the lack of information about the source of relational issues and causes a disturbance because one can’t thoroughly explain and find a solution for a dilemma in the relationship.[12]

Communication scholars have studied this theory and its effects on romantic when coupled with other variables. In romantic relationships studies have shown a relation with the Uncertainty Reduction Theory and its ability to predict the longevity of the relationship. Having information about your partner’s behaviors, feelings, and thoughts play a major in the development of a relationship because makes individuals reference and factor previous experiences so they deal with issues more efficiently. One variable studied in romantic relationships was the amount of time the couple spent communicating through an interactive and/or passive strategy.[11] Observing your partner’s behavior with their family is a way one can see them in their most comfortable environment. This can reveal innate traits that aren’t processed or exploited during direct communication. However, direct communication could affirm mutual interests as well as similarities in personalities.[11] Getting information that allows you to promote your similarities is a way to connect more in a developing relationship.

There are assumptions that uncertainty can encourage individuals to avoid situations or discussions that need to be had in order to develop a healthier relationship. Seeking information to reduce uncertainty has resulted in people portraying an image that favors their partners interests. Unfortunately, if this is the only focus it could leave a lot of issues that need to be discussed. Common relationship problems like punctuality, sensitivity, and communicating schedule conflicts could fester and become more severe than what they initially were. Being transparent about what upsets you about your partner is healthy because it gives them clarity on the do’s and don’ts of the relationship. Keeping the peace is the goal in most relationships but couples often clash because their grievances aren’t effectively communicated. These types of patterns are unhealthy and must be broken if a couple is looking to sustain a healthy relationship with good understanding. Therefore, individuals must be honest with themselves about realizing compatibility rather than disregarding your feelings in order to only make your partner happy.

Situational milieu

Context can include all aspects of social channels and situational milieu.

Situational milieu can be defined as the combination of the social and physical environments in which something takes place. For example, a classroom, a military conflict, a supermarket checkout, and a hospital would be considered situational milieus. Similarly, this includes the season, weather, current physical location and environment.

In order to understand the meaning of what is being communicated, context must be considered.[17] In a hospital context, internal and external noise can have a profound effect on interpersonal communication. External noise consists of influences around the reception that distract from the communication itself.[18] In hospitals, this can often include the sound made by medical equipment or conversations had by team members outside of patient's rooms.[19] Internal noise is described as cognitive causes of interference in a communication transaction.[18] Internal noise in the hospital setting could be health care professionals' own thoughts distracting them from a present conversation with a client.

Channels of communication also contribute to the effectiveness of interpersonal communication. A communication channel can be defined as the medium through which a message is transmitted. There are two distinct types of communication channels: synchronous and asynchronous. Synchronous channels involve communication are present. Examples of synchronous channels include face-to-face co chats, and telephone conversations. Asynchronous communication can be sent and received at different points in time. Examples of this type of channel are text serve as reminders of what has been done and what needs to be done, which can prove to beneficial in a fast-paced health care setting. Some of the disadvantages associated with communication through asynchronous channels are that the sender does not know when the other person will receive the message. Mix-ups and errors can easily occur when clarification is not readily available. On the other hand, when an urgent situation arises, as they commonly do in a hospital environment, communication through synchronous channels is ideal. Benefits of synchronous communication include immediate message delivery, and fewer chances of misunderstandings and miscommunications. A disadvantages of synchronous communication is that it can be difficult to retain, recall, and organize the information that has been given in a verbal message. This is especially true when copious amounts of data has been communicated in a short amount of time. When used appropriately, synchronous and asynchronous communication channels are both efficient ways to communicate and are vital to the functioning of hospitals.[20]

When mistakes occur in hospitals, more often than not, they are a result of communication problems rather than just errors in judgment or negligence.[21] Furthermore, when there is a lack of understanding and cooperation, due to a breakdown in communication in the hospital milieu, it is the patient who suffers the most.[22] Therefore, it is essential to cultivate an environment conducive to effective communication, through appropriate use of communication channels, as well as the elimination, when possible, of distracting internal and external noise.

Cultural and linguistic backgrounds

Linguistics is primarily the study of language that is divided into three broad aspects including the form of language, the meaning of language, and the context or function of language. The first aspect, form is based on the words and sounds of language and uses the words to make sentences that make sense. The second aspect, meaning, focuses on the meaning and significance of the words and sentences that human beings have put together. The third aspect, function, or context is based on recognizing the meaning of the words and sentences being said and using them to understand why a person is communicating.[23]

Culture is a human made concept that helps to define the beliefs, values, attitudes, and customs of a group of people that have similarities to one another in relation to language and location that have helped the people to survive more throughout time.[24] There are two subcultures, which include high-culture and low-culture. High-culture is seen as the part of culture that includes a set of cultural aspects mainly focusing on the arts, such as music, drama and others. Those that are of higher esteem and can access these aspects mostly are a part of this. Low-culture in contrast, has a massive audience and is a term more for popular culture.

Culture has a strong dependence on communication because of the help it provides in the process of exchanging information in the objective to transmit ideas, feelings, and specific situations present in the person's mind.[25] Culture influences our thoughts, feelings and actions, and when communication is occurring there should be an awareness of this.[26] This means the more different an individuals cultural background is, the more different their styles of communication will be.[6] Therefore, the first step before communicating with individuals of other cultures is the importance of being aware of a persons background, ideas and beliefs before there is interpretation of their behaviours in relation to communication. It is stressed that there is an importance of cultural safety which is the recognition of social, economic and political positions of individuals before beginning communication.[27] There are 5 major elements related to culture that affect the communication process:[28]

This is a Communication Diagram showing the two different types of communication that can be done between cultures. It is then further broken down into how you appropriately communicate verbally or non verbally with individuals of different cultures.

- Cultural history

- Religion

- Value (personal and cultural)

- Social organization

- Language

After the initial understanding of culture then communication takes place. Communication between cultures can be done through Verbal communication or Nonverbal communication with a sender and a receiver present. There is emphasis on acknowledgement and understanding of values, beliefs, emotions and behaviours of culturally competent individuals so you are able to adapt and decode the message and respond appropriately.[29]

Influences in Verbal Communication

Culture has influenced Verbal communication in a variety of ways. Linguistics is a large factor in relation to this because different cultures have different language barriers.[30] When communicating verbally with individuals of different cultures it is important to respond appropriately and withhold any judgment. If there is a language barrier between the sender and receiver attempt to seek clarification, do not try not to interpret the meanings of the message.[30] There must be sensitivity present for individuals who are expressing opinions on culture and language. We live in a multicultural time, and this plays an important factor in considering that each individual has their own languages, beliefs and values that are allowed to be expressed.[6] When a verbal response is cultivated, it must be sensitive to another individuals culture.[31]

Influences in Nonverbal Communication

Culture has an influence on our Nonverbal communication in a variety of different factors. For example, in some cultures eye contact is not essential, therefore those who do use eye contact may find it hard to talk or listen to someone who is not looking at them.[6] Another example is touching as a form of greeting may be perceived as impolite to some cultures whereas it is seen as a norm to others.[28] It is important to acknowledge these cultural differences, and be understanding of them so better non verbal communication can be established.[32]

An example is that culture has a strong process of dependence on communication in the professional field.[25] Therefore, communication constitutes an important part of the quality of care and predominantly influences client and resident satisfaction; it is a core element of care and is a fundamentally required skill. Still, language can be expressed in different aspects although the most common process is the verbal and nonverbal communication. Hence, body language does a key factor in the process to communicate and interact which other. For example, the nurse-patient relationship is primarily mediated by verbal and nonverbal communication, so both aspects need to be understood.

Developmental Progress (maturity)

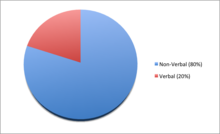

This pie chart shows that 80% of communication is non-verbal and 20% of communication is verbal. This demonstrates how important non-verbal communication is in infants.

This pyramid demonstrates the relationship between interpersonal communication and the stages of development. The downward formation of the triangle represents how much language is developed during that growth stage. The greatest amount of development occurs in the stage of infancy. As the triangle gets smaller, the development occurs less frequently and in a lesser amount.

The development of communication throughout one's lifetime is crucial because it is required in almost every aspect of human life. Majority of language development happens during infancy and early childhood. It is very important that infants learn the principles of communication earlier on in their development. The following information can be used to adapt to the specific attributes in each level of development in order to effectively communicate with an individual of these ages.[33] The amount of communication and language development that happen in different stages of life include:

0-1 Years of Age:

- During the period of infancy, an infant mainly uses non-verbal communication (mostly gestures) to effectively communicate with others. In the first period of a newborn's life crying is the only means of communication, which is used to demonstrate their needs and wants. Infants, 1-5 months old have different tones of crying that indicate their emotions. Also, within the 1 to 5 month stage the newborn begins laughing. When the infants are 6-7 months old they begin to respond to their own name, yell and squeal, and distinguish emotions based on the tone of voice of the mother and father. Between 7 and 10 months the infant starts putting words together, for example "mama" and "dada". These words are simply babbled by the infant, lacking meaning and significance. When the infant turns 12 months of age they start to put meaning behind those once babbled words and can start imitate any sounds they hear, for example animal sounds. Verbal communication begins to occur at the age of 10-12 months. It starts with the act of imitating adult language and slowly developing the words "mama" and "dada". They can also respond to simple commands. The non-verbal communication of infants includes the use of gaze, head orientation and body positioning, this enables them to communicate without the use of language yet displays effectively what they are trying to convey to others. Gestures are also widely used as an act of communication. All these stages can be delayed if the parents do not communicate with their infant on a daily basis.[34]

Nonverbal communication begins with the comprehension of parents and how they use it effectively in conversation. Infants are able to breakdown what adults and others are saying to them, they then use their comprehension of this communication to produce their own.[35] Infants have a remarkable capacity to adjust their own behaviour in social interactions. Infant's readiness to communicate completely effects their language development. Variations in the amount of interaction between a mother and her child will effect certain aspects of the infant's language performance.[36]

1-2 Years of Age:

- Verbal and nonverbal communication are both used at this stage of development. At 12 months, children start to repeat the words they hear. The parental role is a large influence on the development of communication in children. Adults are used as a point of reference for children in terms of the sound of words and what they mean in context of the conversation. Children learn much of their verbal communication through repetition and observing others. If parents do not speak to their children at this age it can become quite difficult for them to learn the essentials of conversation etiquette. The vocabulary of a 1-2 year old should consist of 50 words yet can hold up to 500. Gestures that were used earlier on in development begin to be replaced by words and eventually are only used when needed. Verbal communication is chosen over nonverbal as development progresses.[37]

2-3 Years of Age:

- Children ages 2-3 experience something known as the turn-taking style. In this stage, children communicate best in a turn-taking style as it brings cohesive interaction into their channel of communication and a conversational structure is in place, which makes it easier for verbal communication to develop. This also teaches them skills of patience, kindness, and respect early on as they learn from the direction of elders that one person is able to speak at a given time. This creates biological patterns for the child and creates interactional synchrony during their preverbal routines which shapes their interpersonal communication skills early on in their development.[38] Children during this stage in their life also go through a recognition and continuity phase. Children start to see that shared awareness is a factor in communication along with their development of symbolic direction of language. This especially affects the relationship between the child and the caregiver because this is a crucial part of self-discovery for the child and taking ownership over their own actions in a continuous manner.[38]

3-5 Years of Age:

- This age group can also be classified as the pre-school age group as children are still learning how to form abstract thoughts and are still communicating concretely. Children begin to be fluent while connecting sounds, syllables, and linking words that make sense together in one thought. They begin to participate in short conversations with others. Stuttering can be an effect of newly acquired verbal communication for children when they are around the age of three and can generally result in slowed-down speech with a few letter enunciation errors (f, v, s, z).[39] At the beginning of this stage toddlers tend to be missing function words and misunderstand how to use the correct tenses when they are communicating. As they continue to develop their communication skills they start including functional words, pronouns, and auxiliary verbs.[40] While conversing with adults, this is the stage when most children can pick up on emotional cues of the tone of the conversation. If negative feedback is distinguished by the child, this ends with fear and an understanding of the verbal and nonverbal cues that the child is now aware of and will avoid in the future. They learn skills like taking turns and ideas of when communication is acceptable. Toddlers develop the skills to listen and partially understand what another person is saying and can develop an appropriate response.

5-10 Years of Age:

- A lot of language development that happens during this time period takes place in a school setting. During the beginning of the school age years, children’s vocabulary expands through increases in reading. Increased exposure to reading also helps school-aged children learn more difficult grammatical forms, including plurals and pronouns. These changes improve their communication skills because the message of what they are trying to say will become clearer. They also begin to develop metalinguistic awareness which allows them to reflect and more clearly understand the language they use. This ability helps them understand jokes and riddles because they can comprehend the differences in the words. Having the skills to read well is a gateway for learning new vernacular at a young age and having the confidence in complex word choices while talking with adults. This is an important developmental part socially and physiologically for the child.[41] School-aged children can easily be influenced through communication and gestures.[39] As children continue to learn communication, they realize the difference between forms of intentions and that there are numerous different ways to express the same intent, with different meaning. This new form of message complexity shows growth in a child's interpersonal communication and how they interpret language of others.[38]

10-18 Years of Age:

- By the age of 10, individuals can participate fully and understand the purpose of their conversations. During the end of this period the individual reaches maturity influencing their cognitive potential, affecting their communication. During this time, there are rises in the sophistication and effectiveness for communication skills. Adolescents go through changes in social interactions and cognitive development which influences the way they communicate.[42] The individual has reached a higher level of education which has increased their vocabulary and grammar. However, adolescents tend to use colloquial speech (slang) which can increase confusion and misunderstandings.[39] Also, an individual’s interpersonal communication depends on who they are communicating with. Their relationships change influencing how they communicate with others. During this period, adolescents tend to communicate less with their parents and more with their friends. When discussions are initiated in different channels of communication, attitude and predispositions are key factors that drive the individual to discuss their feelings. This also shows that respect in communication is a trait in interpersonal communication that is built on throughout development.[41] The end of this adolescent stage is the basis for communication in the adult stage.

Theories

Uncertainty reduction theory

Uncertainty reduction theory comes from the sociopsychological perspective. It addresses the basic process of how we gain knowledge about other people. According to the theory, people have difficulty with uncertainty. They want to be able to predict behavior, and therefore, they are motivated to seek more information about people.[43]

The theory argues that strangers, upon meeting, go through certain steps and checkpoints in order to reduce uncertainty about each other and form an idea of whether one likes or dislikes the other. As we communicate, we are making plans to accomplish our goals.

At highly uncertain moments, we become more vigilant and rely more on data available in the situation. When we are less certain, we lose confidence in our own plans and make contingency plans. The theory also says that higher levels of uncertainty create distance between people and that non-verbal expressiveness tends to help reduce uncertainty.[44]

Constructs include level of uncertainty, nature of the relationship and ways to reduce uncertainty. Underlying assumptions include that an individual will cognitively process the existence of uncertainty and take steps to reduce it. The boundary conditions for this theory are that there must be some kind of outside social situation trigger and internal cognitive process.

According to the theory, we reduce uncertainty in three ways:

- Passive strategies: observing the person.

- Active strategies: asking others about the person or looking up info.

- Interactive strategies: asking questions, self-disclosure.

Uncertainty Reduction Theory is most applicable to the initial interaction context, and in response to this limited context, scholars have extended the uncertainty framework with theories that describe uncertainty manangement, more broadly, and motivated information management. These subsequent theories give a broader conceptualization of how uncertainty operates in interpersonal communication as well as how uncertainty motivates individuals to seek information.

Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory falls under the symbolic interaction perspective. The theory predicts, explains, and describes when and why people reveal certain information about themselves to others. The social exchange theory uses Thibaut and Kelley's (1959) theory of interdependence. This theory states that "relationships grow, develop, deteriorate, and dissolve as a consequence of an unfolding social-exchange process, which may be conceived as a bartering of rewards and costs both between the partners and between members of the partnership and others" (Huston & Burgess, 1979, p. 4). Social exchange theory argues the major force in interpersonal relationships is the satisfaction of both people's self-interest. Theorists say self-interest is not necessarily a bad thing and that it can actually enhance relationships.[45]

According to the theory, human interaction is like an economic transaction, in that you may seek to maximize rewards and minimize costs. You will reveal information about yourself when the cost-rewards ratio is acceptable to you. As long as rewards continue to outweigh costs, a couple will become increasingly intimate by sharing more and more personal information. The constructs of this theory include discloser, relational expectations, and perceived rewards or costs in the relationship. Levinger (1965, 1976) discussed marital success as dependent on all the rewarding things within the relationship, such as emotional security and sexual fulfillment. He also argued that marriages either succeed or fail based on the barriers to leave the relationship, like financial hardships, and the presence of alternative attractions, like infidelity. Levinger stated that marriages will fail when the attractions of the partners lessen, the barriers to leave the spouse are weak, and the alternatives outside of the relationship are appealing.[44]

The underlying assumptions include that humans weigh out rewards versus costs when developing a relationship. The boundary conditions for this theory are that at least two people must be having some type of interaction.

Social exchange also ties in closely with social penetration theory.

Symbolic interaction

Symbolic interaction comes from the sociocultural perspective in that it relies on the creation of shared meaning through interactions with others. This theory focuses on the ways in which people form meaning and structure in society through interactions. People are motivated to act based on the meanings they assign to people, things, and events.[46]

Symbolic interaction argues the world is made up of social objects that are named and have socially determined meanings. When people interact over time, they come to shared meaning for certain terms and actions and thus come to understand events in particular ways.

There are three main concepts in this theory: society, self, and mind.

- Society

- Social acts (which create meaning) involve an initial gesture from one individual, a response to that gesture from another and a result.

- Self

- Self-image comes from interaction with others based on others perceptions.

A person makes sense of the world and defines their "self" through social interactions. One ’s self is a significant object and like all social objects it is defined through social interactions with others. - Mind

- Your ability to use significant symbols to respond to yourself makes thinking possible. You define objects in terms of how you might react to them. Objects become what they are through our symbolic minding process.[44]

Constructs for this theory include creation of meaning, social norms, human interactions, and signs and symbols. An underlying assumption for this theory is that meaning and social reality are shaped from interactions with others and that some kind of shared meaning is reached. The boundary conditions for this theory are there must be numerous people communicating and interacting and thus assigning meaning to situations or objects.

Relational dialectics theory

A dialectical approach to interpersonal communication was developed by scholars Leslie Baxter and Barbara Montgomery. Their dialectical approach revolves around the notions of contradiction, change, praxis, and totality. Influenced by Hegel, Marx, and Bakhtin, the dialectical approach is informed by an epistemology that refers to a method of reasoning by which one searches for understanding through the tension of opposing arguments. Utilizing the dialectical approach, Baxter and Montgomery developed two types of dialectics that function in interpersonal relationships: internal and external. These include autonomy-connection, novelty-predictability, openness-closedness.

In order to understand relational dialectics theory, we must first understand specifically what encompasses the term discourse. Therefore, discourses are "systems of meaning that are uttered whenever we make intelligible utterances aloud with others or in our heads when we hold internal conversations".[47] Now, taking the term discourse and coupling it with Relational Dialectics Theory, it is assumed that this theory "emerges from the interplay of competing discourses".[47]

This theory also poses the primary assumption that, "Dialogue is simultaneously unity and difference".[48] Therefore, these assumptions insinuate the concept of creating meaning within ourselves and others when we communicate. However, it also shows how the meanings within our conversations may be interpreted, understood, and of course misunderstood. Hence, the creation and interpretations we find in our communicative messages may create strains in our communicative acts that can be termed as ‘dialectical tensions.’

So, if we assume the stance that all of our discourse, whether in external conversations or internally within ourselves, has competing properties, then we can take relational dialectics theory and look at what the competing discourses are in our conversations, and then analyze how this may have an effect on various aspects of our lives.

Numerous examples of this can be seen in the daily communicative acts we participate in. However, dialectical tensions within our discourses can most likely be seen in interpersonal communication due to the close nature of interpersonal relationships. The well known proverb "opposites attract, but birds of a feather flock together" exemplifies these dialectical tensions.[49]

The three relational dialectics

In order to understand relational dialectics theory, one must also be aware of the assumption that there are three different types of relational dialectics. These consist of connectedness and separateness, certainty and uncertainty, and openness and closedness.

[50]

Connectedness and separateness

Most individuals naturally desire to have a close bond in the interpersonal relationships we are a part of. However, it is also assumed that no relationship can be enduring without the individuals involved within it also having their time alone to themselves. Individuals who are only defined by a specific relationship they are a part of can result in the loss of individual identity.

Certainty and uncertainty

Individuals desire a sense of assurance and predictability in the interpersonal relationships they are a part of. However, they also desire having a variety in their interactions that come from having spontaneity and mystery within their relationships as well. Like repetitive work, relationships that become bland and monotonous are undesirable.[51][citation needed]

Openness and closedness

In close interpersonal relationships, individuals may often feel a pressure to reveal personal information. This assumption can be supported if one looks at the postulations within social penetration theory, which is another theory used often within the study of communication. This tension may also spawn a natural desire to keep an amount of personal privacy from other individuals. The struggle in this sense, illustrates the essence of relational dialectics.

Coordinated management of meaning

Coordinated management of meaning is a theory assuming that two individuals engaging in an interaction are each constructing their own interpretation and perception behind what a conversation means. A core assumption within this theory includes the belief that all individuals interact based on rules that are expected to be followed while engaging in communication. "Individuals within any social situation first want to understand what is going on and apply rules to figure things out."[52]

There are two different types of rules that individuals can apply in any communicative situation. These include constitutive and regulative rules.

- Constitutive rules

- "are essentially rules of meaning used by communicators to interpret or understand an event or message".[52]

- Regulative rules

- "are essentially rules of action used to determine how to respond or behave".[52]

An example of this can be seen if one thinks of a hypothetical situation in which two individuals are engaging in conversation. If one individual sends a message to the other, the message receiver must then take that interaction and interpret what it means. Often, this can be done on an almost instantaneous level because the interpretation rules applied to the situation are immediate and simple. However, there are also times when one may have to search for an appropriate interpretation of the ‘rules’ within an interaction. This simply depends on each communicator's previous beliefs and perceptions within a given context and how they can apply these rules to the current communicative interaction.

Important to understand within the constructs of this theory is the fact that these "rules" of meaning "are always chosen within a context".[52] Furthermore, the context of a situation can be understood as a framework for interpreting specific events.

The authors of this theory believe that there are a number of different context an individual can refer to when interpreting a communicative event. These include the relationship context, the episode context, the self-concept context, and the archetype context.

- Relationship context

- This context assumes that there are mutual expectations between individuals who are members of a group.

- Episode context

- This context simply refers to a specific event in which the communicative act is taking place.

- Self-concept context

- This context involves one's sense of self, or an individual's personal ‘definition’ of him/herself.

- Archetype context

- This context is essentially one's image of what his or her belief consists of regarding general truths within communicative exchanges.

Furthermore, Pearce and Cronen believe that these specific contexts exist in a hierarchical fashion. This theory assumes that the bottom level of this hierarchy consists of the communicative act. Next, the hierarchy exists within the relationship context, then the episode context, followed by the self-concept context, and finally the archetype context.

Social penetration theory

Developed by Irwin Altman and Dallas Taylor, the social penetration theory was made to provide conceptual framework that describes the development in interpersonal relationships. This theory refers to the reciprocity of behaviors between two people who are in the process of developing a relationship. These behaviors can vary from verbal/nonverbal exchange, interpersonal perceptions, and one's use of the environment around them. The behaviors vary based on the different levels of intimacy that a relationship encounters.[53]

"Onion Theory"

This theory is best known as the "onion theory". This analogy suggests that like an onion, personalities have "layers" that start from the outside (what the public sees) all the way to the core (one's private self). Often, when a relationship begins to develop, it is customary for the individuals within the relationship to undergo a process of self-disclosure.[54] As people divulge information about themselves, their "layers" begin to peel, and once those "layers" peel away they cannot go back; just like you can't put the layers back on an onion.[55]

There are four different stages that social penetration theory encompasses. These stages include the orientation, exploratory affective exchange, affective exchange, and stable exchange.[56]

- Orientation stage

- At first, strangers exchange very little amounts of information and they are very cautious in their interactions.

- Exploratory affective stage

- Next, individuals become somewhat more friendly and relaxed with their communication styles.

- Affective exchange

- In the third stage, there is a high amount of open communication between individuals and typically these relationships consist of close friends or even romantic or platonic partners.

- Stable stage

- The final stage, simply consists of continued expressions of open and personal types of interaction.[56]

If a person speeds through the stages and happens to share too much information too fast, the receiver may view that interaction as negative and a relationship between the two is less likely to form.

Example- Jenny just met Justin because they were sitting at the same table at a wedding. Within minutes of meeting one another, Justin engages in small talk with Jenny. Jenny decides to tell Justin all about her terrible ex-boyfriend and all of the misery he put her through. This is the kind of information you wait to share until stages three or four, not stage one. Due to the fact that Jenny told Justin much more than he wanted to know, he probably views her in a negative aspect and thinks she is crazy, which will most likely prevent any future relationship from happening.

Altman and Taylor believed the social exchange theory principles could accurately predict whether or not people will risk self-disclosure. The principles included, relational outcome, relational stability, and relational satisfaction. This theory assumes that the possible outcome is the stance that which the decision making process of how much information an individual chooses to self disclose is rooted by weighing out the costs and rewards that an individual may acquire when choosing to share personal information. Due to ethical egoism, individuals try to maximize their pleasure and minimize their pain; acting from the motive of self-interest.[57] If a person is more of a hassle to you than an asset, it is more likely that you will dispose of them as a friend because it is decreasing the amount of pleasure in your life.

An example of the social penetration theory can be seen when one thinks of a hypothetical situation such as meeting someone for the first time. The depth of penetration is the degree of intimacy a relationship has accomplished. When two individuals meet for the first time, it is the cultural expectation that only impersonal information will be exchanged. This could include information such as names, occupations, age of the conversation participants, as well as various other impersonal information. However, if both members participating in the dialogic exchange decide that they would like to continue or further the relationship, with the continuation of message exchanges, the more personal the information exchanged will become. Altman and Taylor defined these as the depth and breadth of self-disclosure. According to Griffin, the definition of depth is "the degree of disclosure in a specific area of an individuals life" and the definition of breadth is "the range of areas in an individual's life over which disclosure takes place."[55]

Altman and Taylor discussed the process of four observations that are the reasons a relationship occurs:

- 1. Peripheral items are exchanged more frequently and sooner than private information

- 2. Self-disclosure is reciprocal, especially in the early stages of relationship development

- 3. Penetration is rapid at the start but slows down quickly as the tightly wrapped inner layers are reached

- 4. Depenetration is a gradual process of layer-by-layer withdrawal.[53]

"Computer Mediated Social Penetration"

Also important to note, is the fact that due to current communicative exchanges involving a high amount of computer mediated contexts in which communication occurs, this area of communication should be addressed in regard to social penetration theory as well. Online communication seems to follow a different set of rules. Because much of online communication between people occurs on an anonymous level, individuals are allowed the freedom of foregoing the interpersonal ‘rules’ of self disclosure. Rather than slowly disclosing personal thoughts, emotions, and feelings to others, anonymous individuals online are able to disclose personal information immediately and without the consequence of having their identity revealed. Ledbetter notes that Facebook users self-disclose by posting personal information, pictures, hobbies, and messages. The study finds that the user's level of self-disclosure is directly related to the level of interdependence on others. This may result in negative psychological and relational outcomes as studies show that people are more likely to disclose more personal information than they would in face to face communication, primarily due to the heightened level of control within the context of the online communication medium. In other words, those with poor social skills may prefer the medium of Facebook to show others who they are because they have more control.[58] This may lead to an avoidance of face-to-face communication, which is undoubtedly harmful to interpersonal relationships. The reason that self disclosure is labeled as risky, is because, individuals often undergo a sense of uncertainty and susceptibility in revealing personal information that has the possibility of being judged in a negative way by the receiver. Hence, the reason that face-to-face communication must evolve in stages when an initial relationship develops.

Relational patterns of interaction theory

Relational patterns of interaction theory of the cybernetic tradition, studies how relationships are defined by peoples’ interactions during communication.[59] Gregory Bateson, Paul Watzlawick, et al. laid the groundwork for this theory and went on to become known as the Palo Alto Group. Their theory became the foundation from which scholars in the field of communication approached the study of relationships.

Ubiquitous communication

The Palo Alto Group maintains that a person's presence alone results in them, consciously or not, expressing things about themselves and their relationships with others (i.e., communicating).[60] A person cannot avoid interacting, and even if they do, their avoidance may be read as a statement by others. This ubiquitous interaction leads to the establishment of "expectations" and "patterns" which are used to determine and explain relationship types.

Expectations

Individuals enter communication with others having established expectations for their own behavior as well as the behavior of those they are communicating with. These expectations are either reinforced during the interaction, or new expectations are established which will be used in future interactions. These new expectations are created by new patterns of interaction, established expectations are a result of established patterns of interaction.

Patterns of interaction

Established patterns of interaction are created when a trend occurs regarding how two people interact with each other. There are two patterns of particular importance to the theory which form two kinds of relationships.

Symmetrical relationships

These relationships are established when the pattern of interaction is defined by two people responding to one and other in the same way. This is a common pattern of interaction within power struggles.

Complementary relationships

These relationships are established when the pattern of interaction is defined by two people responding to one and other in opposing ways. An example of such a relationship would be when one person is argumentative while the other is quiet.

Relational control

Relational control refers to who, within a relationship, is in control of it. The pattern of behavior between partners over time, not any individual's behavior, defines the control within a relationship. Patterns of behavior involve individuals’ responses to others’ assertions.

There are three kinds of responses:

- One-down responses are submissive to, or accepting of, another's assertions.

- One-up responses are in opposition to, or counter, another's assertions.

- One-across responses are neutral in nature.

Seth Weiss and Marian Houser add to relational control in a teacher/student context. "Students communicating with instructors for relational purposes hope to develop or maintain a personal relationship; functional reasons aim to seek more information presented and discussed by instructors; students communicating to explain a lack of responsibility utilize an excuse-making motive; participatory motives demonstrate understanding and interest in the class or course material; and students communicating for sycophantic purposes hope to make a favorable impression on their instructor."[61]

Complementary exchanges

A complementary exchange occurs when a partner asserts a one-up message which the other partner responds to with a one-down response. When complementary exchanges are frequently occurring within a relationship, and the parties at each end of the exchange tend to remain uniform, it is a good indication of a complementary relationship existing.

Symmetrical exchanges

Symmetrical exchanges occur when one partner's assertion is countered with a reflective response. So, when a one-up assertion is met with a one-up response, or when a one-down assertions is met with a one-down response, a symmetrical exchange occurs. When symmetrical exchanges are frequently occurring within a relationship, it is a good indication of a symmetrical relationship existing.

Theory of intertype relationships

Socionics has proposed a theory of intertype relationships between psychological types based on a modified version of C.G. Jung's theory of psychological types. Communication between types is described using the concept of information metabolism proposed by Antoni Kępiński. Socionics allocates 16 types of the relations — from most attractive and comfortable up to disputed. The understanding of a nature of these relations helps to solve a number of problems of the interpersonal relations, including aspects of psychological and sexual compatibility. The researches of married couples by Aleksandr Bukalov et al., have shown that the family relations submit to the laws, which are opened by socionics. The study of socionic type allocation in casually selected married couples confirmed the main rules of the theory of intertype relations in socionics.[62][63]

Identity management theory

Falling under the socio-cultural tradition and developed by Tadasu Todd Imahori and William R. Cupach, identity-management theory explains the establishment, development, and maintenance of identities within relationships, as well as changes which occur to identities due to relationships.[64]

Establishing identities

People establish their identities (or faces), and their partners, through a process referred to as "facework".[65] Everyone has a desired identity which they’re constantly working towards establishing. This desired identity can be both threatened and supported by attempting to negotiate a relational identity (the identity one shares with their partner). So, our desired identity is directly influenced by our relationships, and our relational identity by our desired individual identity.

Cultural influence

Identity-management pays significant attention to intercultural relationships and how they affect the relational and individual identities of those involved. How partners of different cultures negotiate with each other, in an effort to satisfy desires for adequate autonomous identities and relational identities, is important to identity-management theory. People take different approaches to coping with this problem of cultural influence.

Tensions within intercultural relationships

Identity freezing occurs when one partner feels like they’re being stereotyped and not recognized as a complex individual. This tends to occur early on in relationships, prior to partners becoming well acquainted with each other, and threatens individuals’ identities. Showing support for oneself, indicating positive aspects of one's cultural identity, and having a good sense of humor are examples of coping mechanisms used by people who feel their identities are being frozen. It is also not uncommon for people in such positions to react negatively, and cope by stereotyping their partner, or totally avoiding the tension.

When tension is due to a partner feeling that their cultural identity is being ignored, it is referred to as a nonsupport problem. This is a threat to one's face, and individuals often cope with it in the same ways people cope with identity freezing.

Self-other faceground, giving in, alternating in their support of each identity, and also by avoiding the issue completely.

Relational stages of identity management

Identity management is an ongoing process which Imahori and Cupach define as having three relational stages.[64] Typically, each stage is dealt with differently by couples.

The trial stage occurs at the beginning of an intercultural relationship when partners are beginning to explore their cultural differences. During this stage, each partner is attempting to determine what cultural identities they want for the relationship. At this stage, cultural differences are significant barriers to the relationship and it is critical for partners to avoid identity freezing and nonsupport. During this stage, individuals are more willing to risk face threats to establish a balance necessary for the relationship.

The enmeshment stage occurs when a relational identity emerges with established common cultural features. During this stage, the couple becomes more comfortable with their collective identity and the relationship in general.

The renegotiation stage sees couples working through identity issues and drawing on their past relational history while doing so. A strong relational identity has been established by this stage and couples have mastered dealing with cultural differences. It is at this stage that cultural difference become part of the relationships and not a tension within them.

Communication privacy management theory

Of the socio-cultural tradition, communication privacy management theory is concerned with how people negotiate openness and privacy in concern to communicated information. This theory focuses on how people in relationships manage boundaries which separate the public from the private.[66]

Boundaries

An individual's private information is protected by the individual's boundaries. The permeability of these boundaries are ever changing, and allow certain parts of the public, access to certain pieces of information belonging to the individual. This sharing occurs only when the individual has weighed their need to share the information against their need to protect themselves. This risk assessment is used by couples when evaluating their relationship boundaries. The disclosure of private information to a partner may result in greater intimacy, but it may also result in the discloser becoming more vulnerable.

Co-ownership of information

When someone chooses to reveal private information to another person, they are making that person a co-owner of the information. Co-ownership comes with rules, responsibilities, and rights which the discloser of the information and receiver of it negotiate. Examples of such rules would be: Can the information be disclosed? When can the information be disclosed? To whom can the information be disclosed? And how much of the information can be disclosed? The negotiation of these rules can be complex, the rules can be explicit as well as implicit, and they can be violated.

Boundary turbulence

What Petronio refers to as "boundary turbulence" occurs when rules are not mutually understood by co-owners, and when a co-owner of information deliberately violates the rules. This usually results in some kind of conflict, is not uncommon, and often results in one party becoming more apprehensive about future revelation of information to the violator.

Cognitive dissonance theory

The theory of cognitive dissonance, part of the Cybernetic Tradition, explains how humans are consistency seekers and attempt to reduce their dissonance, or discomfort, in new situations.[67] The theory was developed in the 1950s by Leon Festinger.[68]

When individuals encounter new information or new experiences, they categorize the information based on their preexisting attitudes, thoughts, and beliefs. If the new encounter does not coincide with their preexisting assumptions, then dissonance is likely to occur. When dissonance does occur, individuals are motivated to reduce the dissonance they experience by avoiding situations that would either cause the dissonance or increase the dissonance. For this reason, cognitive dissonance is considered a drive state that encourages motivation to achieve consonance and reduce dissonance.

An example of cognitive dissonance would be if someone holds the belief that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is important, but they don't regularly work out or eat healthy. They may experience dissonance between their beliefs and their actions. If there is a significant amount of dissonance, they may be motivated to change their attitudes and work out more or eat healthier foods. They may also be inclined to avoid situations that will point out the fact that their attitudes and beliefs are inconsistent, such as avoiding the gym or not reading health reports.

The selection process

- Selective exposure

- is a method for reducing dissonance that only seeking information that is consonant with one's current beliefs, thoughts, or actions.

- Selective attention

- is a method for reducing dissonance by only paying attention to particular information or parts of information that is consonant with current beliefs, thoughts, or actions.

- Selective interpretation

- is a method for reducing dissonance by interpreting ambiguous information so that it seems consistent with one's beliefs, thoughts, or actions.

- Selective retention

- when an individual only remembers information that is consistent with their current beliefs.

Types of cognitive relationships

According to cognitive dissonance theory, there are three types of cognitive relationships: consonant relationships, dissonant relationships, and irrelevant relationships. Consonant relationships are when two elements, such as your beliefs and actions, are in equilibrium with each other or coincide. Dissonant relationships are when two elements are not in equilibrium and cause dissonance. Irrelevant relationships are when two elements do not possess a meaningful relationship with one another, they are unrelated and do not cause dissonance.

Attribution theory

Attribution theory is part of the sociopsychological tradition and explains how individuals go through a process that makes inferences about observed behavior. Attribution theory assumes that we make attributions, or social judgments, as a way to clarify or predict behavior. Attribution theory assumes that we are sense-making creatures and that we draw conclusions of the actions that we observe.

Steps to the attribution process

- The first step of the attribution process is to observe the behavior or action.

- The second step is to make judgments of interactions and the intention of that particular action.

- The last step of the attribution process is making the attribution which will be either internal, where the cause is related to the person, or external, where the cause of the action is circumstantial.

An example of this process is when a student fails a test, an observer may choose to attribute that action to 'internal' causes, such as insufficient study, laziness, or have a poor work ethic. The action might also be attributed to 'external' factors such as the difficulty of the test, or real-world stressors that led to distraction.

We also make attributions of our own behavior. Using this same example, if it were you who received a failing test score you might either make an internal attribution, such as "I just can’t understand this material", or you could make an external attribution, such as "this test was just too difficult."

Fundamental attribution error

As we make attributions, we may fall victim to the fundamental attribution error which is when we overemphasize internal attributions for others and underestimate external attributions.

Actor-observer bias

Similar to the fundamental attribution error, we may overestimate external attributions for our own behavior and underestimate internal attributions.

Expectancy violations theory

Expectancy violations theory is part of the sociopsychological tradition, and explains the relationship between non-verbal message production and the interpretations people hold for those non-verbal behaviors. Individuals hold certain expectations for non-verbal behavior that is based on the social norms, past experience and situational aspects of that behavior. When expectations are either met or violated, we make assumptions of the behavior and judge them to be positive or negative.

Arousal

When a deviation of expectations occurs, there is an increased interest in the situation, also known as arousal. There are two types of arousal:

- Cognitive arousal

- our mental awareness of expectancy deviations

- Physical arousal

- challenges our body faces as a result of expectancy deviations.

Reward valence

When an expectation is not met, we hold particular perceptions as to whether or not that violation is considered rewarding. How an individual evaluates the interaction will determine how they view the positive or negative impact of the violation.

Proxemics

The study of proxemics was originated by Edward T. Hall. The study of proxemics focuses on the use of space to communicate. According to Edward T. Hall's Theory of Personal Space, there are four spaces in which we situate our bodies to communicate.

- Intimate distance

- 0–10 inches. This is often reserved for intimate relationships with significant others. It is also reserved for the parent-child relationship (hugging, cuddling, kisses, etc.)

- Personal distance

- 38 inches – 64 feet. This is often reserved for close friends and acquaintances, such as significant others and close friends. For instance, sitting close to a friend or family member on the couch.

- Social distance

- 54–82 feet. This is often reserved for professional situations, such as interviews and meetings.

- Public distance

- 32 feet or more. This is often reserved for public spaces, such as waiting in an airport, sitting in a waiting room at a doctor's office, or choosing a seat in the movie theater.

Dyadic communication and Relationships

Dyadic communication is the part of a relationship that calls for "something to happen". Partners will either talk or argue with one another during this point of a relationship to bring about change. When partners talk or argue with one another, the relationship may still survive at this point.

Bochner (2000) stresses inherent dialectic in interpersonal communication as the key to healthy marital dyads. He proposes that people in intimate relationships are looking to find an equilibrium point between needing to be open with their partner and needing to protect their partner from the consequences of this openness. Therefore, the communication in romantic, long-term relationships can be viewed as a balance between hiding and revealing. Taking this theory even further, communication within marriages can be viewed as a continuing refinement and elimination of conversational material. The partners of the marriage will still have things to discuss, but as their relationship and communication grows, they can decide when to not speak about an issue, because in complex relationships like marriage, anything can become an issue.

- Conflict resolution

Sillars (1380) and Roloff (1876) expressed that conflict resolution strategies can be categorized as pro-social or anti-social in nature. When an individual is presented with an interpersonal conflict, they can decide how they want to deal with it. They can avoid (anti-social), compete (anti-social), or cooperate (pro-social). It has been learned that one who avoids conflict is less capable of solving problems because they are more constricted. Avoidance has negative effects on dyads.

- The Couples Coping Enhancement Training (CCET)

This program is based on stress, coping, and research on dyads (Bodenmann, 1997a; 2000b). The focus is on individual and dyadic coping to help promote satisfaction within marriage and to help reduce distress within marriages. CCET states three important factors for dyads being successful when they enter counseling programs. Firstly, the dyad's ability to cope with daily stress is a main factor in determining the success or failure of their relationship. Couples need to be educated about ways to manage daily stress so that this stress is not placed on their partner or on their relationship. Secondly, couples who enter counseling to help their relationship must stay in counseling to continue to get reinforcement and encourage about practicing their new methods of communication. Continued counseling will help the couple to maintain their new strategies. Lastly, couples should make use of technology within their counseling. They should use the Internet and seek help online in addition to their counseling program. Having technology that can help couples with immediate problems is a very useful thing.

- Parenting

Many theorists have studied how the relationship between the husband and wife greatly affects the relationship between the parent and child (Belsky, 1990; Parke & Tinsley, 1987). There have been numerous studies done that show how difficult it is to maintain a positive and healthy parent-child relationship when the marriage between the parents is failing. "Spillover," emotional transmission from one family relationship to another, is a likely explanation as to why parents have trouble fostering a good relationship with their children when there are problems within their marriage (Bolger, DeLongis, Kessler, & Wethington, 1989; Repetti, 1987).

New Parenthood and Marital Quality:

New parenthood is a time where there are many adjustments within a family and these adjustments can put a lot of stress on marital dyads. How a couple deals with first-time parenthood directly correlates to their marital satisfaction, amount of conflict within their marriage, and the perceptions of themselves (Glade, Bean, & Vira, 2005). Studies show that transitioning into parenting leads to more marital conflicts and less marital satisfaction. When marital dyads have a child, their once dyadic dynamic relationships quickly changes to a triadic relationship, creating a shift in roles. New topics for discussion between the married couple, such as household labor, finances, and child care responsibilities, can lead to major conflicts. It is important for couples to identify ways that may help them maintain marital satisfaction while coping with becoming parents.

Pedagogical communication

Pedagogical communication is an action in which the body, being a part of a relational whole, performs a fundamental role. As such, instructional communication (pedagogical communication) is often conceptualized as a form of interpersonal communication. Various studies on the interaction between teacher and student confirms that there is a strong correlation between the teacher's nonverbal behavior (such as immediacy), as well as verbal behavior (such as out of class communication (OCC)) and the students' level of motivation and proficiency. Nonverbal communication serves as a vehicle for the teacher's affections, intentions, and attitudes towards students, and vice versa. For this reason, the concept of "immediacy" is often studied in pedagogical communication. Immediacy is the perception of physical, emotional, or psychological proximity created by positive communicative behaviors – in the pedagogical relationship, it refers specifically to the communication between teachers and students (Richmond, 2002 ; Sibii, 2010). Studies examining interpersonal communication in instructional communication are published in Communication Education.[69]

Good communication between teachers and young students is thought to improve the test scores of the students. Some parents of students at The William T. Harris School were interviewed and stated that they can tell how good a teacher is just by watching them in the classroom setting. Observing how teachers talk to their students and how they promote communication between their students can lead to conclusions about how well these students will score on standardized tests. Parents of students at The William T. Harris School have admitted that they do not always trust the publicized rankings of teachers; however, they stated that there are strong similarities between their children's grades and their impressions of their children's teachers.

Social networks