Gabapentin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Neurontin, others[1] |

| Synonyms | CI-945; GOE-3450; DM-1796 (Gralise) |

AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a694007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Gabapentinoid |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 27–60% (inversely proportional to dose; a high fat meal also increases bioavailability)[2][3] |

| Protein binding | Less than 3%[2][3] |

| Metabolism | Not significantly metabolized[2][3] |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 7 hours[2][3] |

| Excretion | Renal[2][3] |

| Identifiers | |

IUPAC name

| |

| CAS Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| IUPHAR/BPS |

|

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII |

|

| KEGG |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

PDB ligand |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.056.415 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

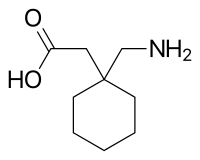

| Formula | C9H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 171.237 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

SMILES

| |

InChI

| |

.mw-parser-output .nobold{font-weight:normal} (verify) | |

Gabapentin (sold under the brand name Neurontin, among others) is a medication which is used to treat partial seizures, neuropathic pain, hot flashes, and restless legs syndrome.[4][5] It is recommended as one of a number of first-line medications for the treatment of neuropathic pain caused by diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and central neuropathic pain.[6] About 15% of those given gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia have a measurable benefit.[7] Gabapentin is taken by mouth.[4]

Common side effects of gabapentin include sleepiness and dizziness.[4] Serious side effects include an increased risk of suicide, aggressive behavior, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.[4] It is unclear if it is safe during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[8] Lower doses are recommended in those with kidney disease associated with a low glomerular filtration rate.[4] Gabapentin is a gabapentinoid: it has a structure similar to that of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and acts by inhibiting certain calcium channels.[9][10][11]

Gabapentin was first approved for use in 1993.[12] It has been available as a generic medication in the United States since 2004.[4] The wholesale price in the developing world as of 2015[update] was about US$10.80 per month;[13] in the United States, it was US$100 to US$200.[14] In 2016 it was the 11th most prescribed medication in the United States with more than 44 million prescriptions.[15] During the 1990s, Parke-Davis, a subsidiary of Pfizer, began using a number of illegal techniques to encourage physicians in the United States to use gabapentin for off-label (unapproved) uses.[16] They have paid out millions of dollars to settle lawsuits regarding these activities.[17]

.mw-parser-output .toclimit-2 .toclevel-1 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-3 .toclevel-2 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-4 .toclevel-3 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-5 .toclevel-4 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-6 .toclevel-5 ul,.mw-parser-output .toclimit-7 .toclevel-6 ul{display:none}

Contents

1 Medical uses

1.1 Seizures

1.2 Neuropathic pain

1.3 Migraine

1.4 Anxiety disorders

1.5 Other uses

2 Side effects

2.1 Suicide

2.2 Cancer

2.3 Abuse and addiction

2.4 Withdrawal syndrome

3 Overdose

4 Pharmacology

4.1 Pharmacodynamics

4.2 Pharmacokinetics

4.2.1 Absorption

4.2.2 Distribution

4.2.3 Metabolism

4.2.4 Elimination

5 Chemistry

5.1 Synthesis

6 History

7 Society and culture

7.1 Sales

7.2 FDA approval

7.3 Off-label promotion

7.3.1 Franklin v. Pfizer case

7.4 Brand names

7.5 Related drugs

7.6 Recreational use

8 Veterinary use

9 References

10 External links

Medical uses

Gabapentin is used primarily to treat seizures and neuropathic pain.[18][19] It is primarily administered by mouth, with a study showing that "rectal administration is not satisfactory".[20] It is also commonly prescribed for many off-label uses, such as treatment of anxiety disorders,[21][22]insomnia, and bipolar disorder.[21] There are, however, concerns regarding the quality of the trials conducted and evidence for some such uses, especially in the case of its use as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder.[23]

Seizures

Gabapentin is approved for treatment of focal seizures[24] and mixed seizures. There is insufficient evidence for its use in generalized epilepsy.[25]

Neuropathic pain

A 2018 review found that gabapentin was of no benefit in sciatica nor low back pain.[26]

A 2010 European Federation of Neurological Societies task force clinical guideline recommended gabapentin as a first-line treatment for diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, or central pain. It found good evidence that a combination of gabapentin and morphine or oxycodone or nortriptyline worked better than either drug alone; the combination of gabapentin and venlafaxine may be better than gabapentin alone.[6]

A 2017 Cochrane review found evidence of moderate quality showing a reduction in pain by 50% in about 15% of people with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic neuropathy.[7] Evidence finds little benefit and significant risk in those with chronic low back pain.[27] It is not known if gabapentin can be used to treat other pain conditions, and no difference among various formulations or doses of gabapentin was found.[7]

A 2010 review found that it may be helpful in neuropathic pain due to cancer.[28] It is not effective in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy[29] and does not appear to provide benefit for complex regional pain syndrome.[30]

A 2009 review found gabapentin may reduce opioid use following surgery, but does not help with post-surgery chronic pain.[31] A 2016 review found it does not help with pain following a knee replacement.[32]

It appears to be as effective as pregabalin for neuropathic pain and costs less.[33] All doses appear to result in similar pain relief.[34]

Migraine

The American Headache Society (AHS) and American Academy of Neurology (AAN) guidelines classify gabapentin as a drug with "insufficient data to support or refute use for migraine prophylaxis."[35] Furthermore, a 2013 Cochrane review concluded that gabapentin was not useful for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults.[36]

Anxiety disorders

Gabapentin has been used off-label for the treatment of anxiety disorders. However, there is dispute over whether evidence is sufficient to support it being routinely prescribed for this purpose.[21][22][37][38]

Other uses

Gabapentin may be useful in the treatment of comorbid anxiety in bipolar patients (however, not the manic or depressive episodes themselves).[23][39][40] Gabapentin may be effective in acquired pendular nystagmus and infantile nystagmus (but not periodic alternating nystagmus).[41][42] It is effective in hot flashes.[43][44][45] It may be effective in reducing pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis.[46] Gabapentin may reduce symptoms of alcohol withdrawal (but it does not prevent the associated seizures).[47] There is some evidence for its role in the treatment of alcohol use disorder; the 2015 VA/DoD guideline on substance use disorders lists gabapentin as a "weak for" and is recommended as a second-line agent.[48] Use for smoking cessation has had mixed results.[49][50] Gabapentin is effective in alleviating itching in kidney failure (uremic pruritus)[51] and itching of other causes.[52] It is an established treatment of restless legs syndrome.[53] Gabapentin may help sleeping problems in people with restless legs syndrome and partial seizures.[54][55] Gabapentin may be an option in essential or orthostatic tremor.[56][57][58]

Gabapentin is not effective alone as a mood-stabilizing treatment for bipolar disorder.[21] There is insufficient evidence to support its use in obsessive–compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.[citation needed] Gabapentin does not appear effective for the treatment of tinnitus.[59]

Side effects

The most common side effects of gabapentin include dizziness, fatigue, drowsiness, ataxia, peripheral edema (swelling of extremities), nystagmus, and tremor.[60] Gabapentin may also produce sexual dysfunction in some patients, symptoms of which may include loss of libido, inability to reach orgasm, and erectile dysfunction.[61][62] Gabapentin should be used carefully in patients with renal impairment due to possible accumulation and toxicity.[63]

Suicide

In 2009 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning of an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in patients taking some anticonvulsant drugs, including gabapentin,[64] modifying the packaging inserts to reflect this.[60] A 2010 meta-analysis supported the increased risk of suicide associated with gabapentin use.[65]

Cancer

An increase in formation of adenocarcinomas was observed in rats during preclinical trials; however, the clinical significance of these results remains undetermined. Gabapentin is also known to induce pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas in rats through an unknown mechanism, perhaps by stimulation of DNA synthesis; these tumors did not affect the lifespan of the rats and did not metastasize.[66]

Abuse and addiction

Surveys suggest that approximately 1.1 percent of the general population and 22 percent of those attending addiction facilities have a history of abuse of gabapentin.[67][68] However, as of 2017[update], Kentucky has become the first state among the United States to classify gabapentin as a schedule V controlled substance statewide.[69]

Withdrawal syndrome

Tolerance and withdrawal symptoms are a common occurrence in prescribed therapeutic users as well as non-medical recreational users. Withdrawal symptoms typically emerge within 12 hours to 7 days after stopping gabapentin.[67][68]

Overdose

Through excessive ingestion, accidental or otherwise, persons may experience overdose symptoms including drowsiness, sedation, blurred vision, slurred speech, somnolence and possibly death, if a very high amount was taken, particularly if combined with alcohol. For overdose considerations, serum gabapentin concentrations may be measured for confirmation.[70]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Gabapentin is a gabapentinoid, or a ligand of the auxiliary α2δ subunit site of certain voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), and thereby acts as an inhibitor of α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs.[71][10] There are two drug-binding α2δ subunits, α2δ-1 and α2δ-2, and gabapentin shows similar affinity for (and hence lack of selectivity between) these two sites.[10] Gabapentin is selective in its binding to the α2δ VDCC subunit.[71][72] Despite the fact that gabapentin is a GABA analogue, and in spite of its name, it does not bind to the GABA receptors, does not convert into GABA or another GABA receptor agonist in vivo, and does not modulate GABA transport or metabolism.[71][11] There is currently no evidence that the effects of gabapentin are mediated by any mechanism other than inhibition of α2δ-containing VDCCs.[73][71] In accordance, inhibition of α2δ-1-containing VDCCs by gabapentin appears to be responsible for its anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects.[71][73]

In one study, the affinity (Ki) value of gabapentin for the α2δ subunit expressed in rat brain was found to be about 50 nM.[74] The endogenous α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which closely resemble gabapentin and the other gabapentinoids in chemical structure, are apparent ligands of the α2δ VDCC subunit with similar affinity as the gabapentinoids (e.g., IC50 = 71 nM for L-isoleucine), and are present in human cerebrospinal fluid at micromolar concentrations (e.g., 12.9 µM for L-leucine, 4.8 µM for L-isoleucine).[75] It has been theorized that they may be the endogenous ligands of the subunit and that they may competitively antagonize the effects of gabapentinoids.[75][76] In accordance, while gabapentinoids like gabapentin and pregabalin have nanomolar affinities for the α2δ subunit, their potencies in vivo are in the low micromolar range, and competition for binding by endogenous L-amino acids has been said to likely be responsible for this discrepancy.[73]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Gabapentin is absorbed from the intestines by an active transport process mediated via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, SLC7A5), a transporter for amino acids such as L-leucine and L-phenylalanine.[10][71][77] Very few (less than 10 drugs) are known to be transported by this transporter.[78] Gabapentin is transported solely by the LAT1,[77][79] and the LAT1 is easily saturable, so the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin are dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses.[10]Gabapentin enacarbil is transported not by the LAT1 but by the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and the sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (SMVT), and no saturation of bioavailability has been observed with the drug up to a dose of 2,800 mg.[80]

The oral bioavailability of gabapentin is approximately 80% at 100 mg administered three times daily once every 8 hours, but decreases to 60% at 300 mg, 47% at 400 mg, 34% at 800 mg, 33% at 1,200 mg, and 27% at 1,600 mg, all with the same dosing schedule.[79][80] Food increases the area-under-curve levels of gabapentin by about 10%.[79] Drugs that increase the transit time of gabapentin in the small intestine can increase its oral bioavailability; when gabapentin was co-administered with oral morphine (which slows intestinal peristalsis),[81] the oral bioavailability of a 600 mg dose of gabapentin increased by 50%.[79] The oral bioavailability of gabapentin enacarbil (as gabapentin) is greater than or equal to 68%, across all doses assessed (up to 2,800 mg), with a mean of approximately 75%.[80][10]

Gabapentin at a low dose of 100 mg has a Tmax (time to peak levels) of approximately 1.7 hours, while the Tmax increases to 3 to 4 hours at higher doses.[10] Food does not significantly affect the Tmax of gabapentin and increases the Cmax of gabapentin by approximately 10%.[79] The Tmax of the instant-release (IR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil (as active gabapentin) is about 2.1 to 2.6 hours across all doses (350–2,800 mg) with single administration and 1.6 to 1.9 hours across all doses (350–2,100 mg) with repeated administration.[82] Conversely, the Tmax of the extended-release (XR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil is about 5.1 hours at a single dose of 1,200 mg in a fasted state and 8.4 hours at a single dose of 1,200 mg in a fed state.[82]

Distribution

Gabapentin crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the central nervous system.[71] However, due to its low lipophilicity,[79] gabapentin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier.[77][71][83][84] The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[85] and transports gabapentin across into the brain.[77][71][83][84] As with intestinal absorption of gabapentin mediated by LAT1, transportation of gabapentin across the blood–brain barrier by LAT1 is saturable.[77] It does not bind to other drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) or OCTN2 (SLC22A5).[77] Gabapentin is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1%).[79]

Metabolism

Gabapentin undergoes little or no metabolism.[10][79] Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil, which acts as a prodrug of gabapentin, must undergo enzymatic hydrolysis to become active.[10][80] This is done via non-specific esterases in the intestines and to a lesser extent in the liver.[10]

Elimination

Gabapentin is eliminated renally in the urine.[79] It has a relatively short elimination half-life, with a reported value of 5.0 to 7.0 hours.[79] Similarly, the terminal half-life of gabapentin enacarbil IR (as active gabapentin) is short at approximately 4.5 to 6.5 hours.[82] The elimination half-life of gabapentin has been found to be extended with increasing doses; in one series of studies, it was 5.4 hours for 200 mg, 6.7 hours for 400 mg, 7.3 hours for 800 mg, 9.3 hours for 1,200 mg, and 8.3 hours for 1,400 mg, all given in single doses.[82] Because of its short elimination half-life, gabapentin must be administered 3 to 4 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels.[80] Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil is taken twice a day and gabapentin XR (brand name Gralise) is taken once a day.[86]

Chemistry

Chemical structures of GABA, gabapentin, and two other gabapentinoids, pregabalin and phenibut.

Gabapentin was designed by researchers at Parke-Davis to be an analogue of the neurotransmitter GABA that could more easily cross the blood–brain barrier.[9] It is a 3-substituted derivative of GABA; hence, it is a GABA analogue, as well as a γ-amino acid.[87][72] Specifically, gabapentin is a derivative of GABA with a cyclohexane ring at the 3 position (or, somewhat inappropriately named, 3-cyclohexyl-GABA).[88][89][90] Gabapentin also closely resembles the α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, and this may be of greater relevance in relation to its pharmacodynamics than its structural similarity to GABA.[75][76][88] In accordance, the amine and hydroxyl groups are not in the same orientation as they are in the GABA,[9] and they are more conformationally constrained.[91]

Synthesis

A chemical synthesis of gabapentin has been described.[92]

History

Gabapentin was developed at Parke-Davis and was first described in 1975.[9][93] Under the brand name Neurontin, it was first approved in May 1993 for the treatment of epilepsy in the United Kingdom, and was marketed in the United States in 1994.[94][95] Subsequently, gabapentin was approved in the United States for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in May 2002.[96] A generic version of gabapentin first became available in the United States in 2004.[97] An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration, under the brand name Gralise, was approved in the United States for the treatment postherpetic neuralgia in January 2011.[98][99] Gabapentin enacarbil, under the brand name Horizant, was introduced in the United States for the treatment of restless legs syndrome in April 2011 and was approved for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in June 2012.[100]

Society and culture

Sales

Gabapentin is best known under the brand name Neurontin manufactured by Pfizer subsidiary Parke-Davis. A Pfizer subsidiary named Greenstone markets generic gabapentin.

In December 2004 the FDA granted final approval to a generic equivalent to Neurontin made by the Israeli firm Teva.

Neurontin began as one of Pfizer's best selling drugs; however, Pfizer was criticized and under litigation for its marketing of the drug. Pfizer faced allegations that Parke-Davis marketed the drug for at least a dozen off-label uses that the FDA had not approved.[16][101] It has been used as a mainstay drug for migraines, even though it was not approved for such use in 2004.[102]

FDA approval

Gabapentin was originally approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 1993, for use as an adjuvant (effective when added to other antiseizure drugs) medication to control partial seizures in adults; that indication was extended to children in 2000.[103] In 2004, its use for treating postherpetic neuralgia (neuropathic pain following shingles) was approved.[103][104]

Off-label promotion

Although some small, non-controlled studies in the 1990s—mostly sponsored by gabapentin's manufacturer—suggested that treatment for bipolar disorder with gabapentin may be promising,[46] the preponderance of evidence suggests that it is not effective.[105] Subsequent to the corporate acquisition of the original patent holder, the pharmaceutical company Pfizer admitted that there had been violations of FDA guidelines regarding the promotion of unproven off-label uses for gabapentin in the Franklin v. Pfizer case.

Reuters reported on 25 March 2010, that "Pfizer Inc violated federal racketeering law by improperly promoting the epilepsy drug Neurontin ... Under federal RICO law the penalty is automatically tripled, so the finding will cost Pfizer $141 million."[106] The case stems from a claim from Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Inc. that "it was misled into believing Neurontin was effective for off-label treatment of migraines, bipolar disorder and other conditions. Pfizer argued that Kaiser physicians still recommend the drug for those uses."[107]

Bloomberg News reported "during the trial, Pfizer argued that Kaiser doctors continued to prescribe the drug even after the health insurer sued Pfizer in 2005. The insurer's website also still lists Neurontin as a drug for neuropathic pain, Pfizer lawyers said in closing argument."[108]

The Wall Street Journal noted that Pfizer spokesman Christopher Loder said, "We are disappointed with the verdict and will pursue post-trial motions and an appeal."[109] He would later add that "the verdict and the judge's rulings are not consistent with the facts and the law."[106]

Franklin v. Pfizer case

According to the San Francisco Chronicle, off-label prescriptions accounted for roughly 90 percent of Neurontin sales.[110]

While off-label prescriptions are common for a number of drugs, marketing of off-label uses of a drug is not.[16] In 2004, Warner-Lambert (which subsequently was acquired by Pfizer) agreed to plead guilty for activities of its Parke-Davis subsidiary, and to pay $430 million in fines to settle civil and criminal charges regarding the marketing of Neurontin for off-label purposes. The 2004 settlement was one of the largest in U.S. history, and the first off-label promotion case brought successfully under the False Claims Act.

Brand names

Gabapentin was originally marketed under the brand name Neurontin. Since it became generic, it has been marketed worldwide using over 300 different brand names.[1] An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration was introduced in 2011 for postherpetic neuralgia under the brand name Gralise.[111]

A capsule of gabapentin.

Related drugs

Parke-Davis developed a drug called pregabalin as a successor to gabapentin.[112] Pregabalin was brought to market by Pfizer as Lyrica after the company acquired Warner-Lambert. Pregabalin is related in structure to gabapentin.[113] Another new drug atagabalin has been trialed by Pfizer as a treatment for insomnia.[114]

A prodrug form (gabapentin enacarbil)[115] was approved in 2011 under the brand name Horizant for the treatment of moderate-to-severe restless legs syndrome[116] and in 2012 for postherpetic neuralgia in adults.[117] It was designed for increased oral bioavailability over gabapentin.[118][119]

Recreational use

Also known on the streets as "Johnnies" or "Gabbies",[120] gabapentin is increasingly being abused and misused for its euphoric effects.[121][122]

Veterinary use

In cats, gabapentin can be used as an analgesic in multi-modal pain management.[123] It is also used as an anxiety medication to reduce stress in cats for travel or vet visits.[124]

Gabapentin is also used for some animal treatments, but some formulations (especially liquid forms) meant for human use contain the sweetener xylitol, which is toxic to dogs.[125]

References

^ ab Drugs.com international listings for Gabapentin Archived 16 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Page accessed 9 February 2016

^ abcde "Neurontin, Gralise (gabapentin) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2014..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abcde Goa KL, Sorkin EM (September 1993). "Gabapentin. A review of its pharmacological properties and clinical potential in epilepsy". Drugs. 46 (3): 409–427. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346030-00007. PMID 7693432.

^ abcdef "Gabapentin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 23 Oct 2015.

^ Wijemanne S, Jankovic J (June 2015). "Restless legs syndrome: clinical presentation diagnosis and treatment". Sleep Medicine. 16 (6): 678–90. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.03.002. PMID 25979181.

^ ab Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Nurmikko T (September 2010). "EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision". European Journal of Neurology. 17 (9): 1113–e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. PMID 20402746.

^ abc Wiffen PJ, Derry S, Bell RF, Rice AS, Tölle TR, Phillips T, Moore RA (June 2017). "Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6: CD007938. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub4. hdl:10044/1/52908. PMID 28597471.

^ "Gabapentin Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

^ abcd Sneader, Walter (2005). Drug Discovery: A History. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-470-01552-0. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ abcdefghij Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (November 2016). "2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098.

^ ab Uchitel OD, Di Guilmi MN, Urbano FJ, Gonzalez-Inchauspe C (2010). "Acute modulation of calcium currents and synaptic transmission by gabapentinoids". Channels. 4 (6): 490–6. doi:10.4161/chan.4.6.12864. PMID 21150315.

^ Pitkänen A, Schwartzkroin PA, Moshé SL (2005). Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. Burlington: Elsevier. p. 539. ISBN 978-0-08-045702-4. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

^ "Gabapentin". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

^ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-284-05756-0.

^ "The Top 300 of 2019". clincalc.com. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

^ abc Henney JE (August 2006). "Safeguarding patient welfare: who's in charge?". Annals of Internal Medicine. 145 (4): 305–7. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00013. PMID 16908923.

^ Stempel J (2 June 2014). "Pfizer to pay $325 million in Neurontin settlement". U.S. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

^ "Gabapentin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

^ Patel R, Dickenson AH (April 2016). "Mechanisms of the gabapentinoids and α 2 δ-1 calcium channel subunit in neuropathic pain". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 4 (2): e00205. doi:10.1002/prp2.205. PMC 4804325. PMID 27069626.

^ Kriel RL, Birnbaum AK, Cloyd JC, Ricker BJ, Jones Saete C, Caruso KJ (November 1997). "Failure of absorption of gabapentin after rectal administration". Epilepsia. 38 (11): 1242–4. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01223.x. PMID 9579927.

^ abcd Sobel SV (5 November 2012). Successful Psychopharmacology: Evidence-Based Treatment Solutions for Achieving Remission. W. W. Norton. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-393-70857-8. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ ab Reynolds DJ, Coleman J, Aronson J (10 November 2011). Oxford Handbook of Practical Drug Therapy. Oxford University Press. p. 765. ISBN 978-0-19-956285-5. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ ab Vedula SS, Bero L, Scherer RW, Dickersin K (November 2009). "Outcome reporting in industry-sponsored trials of gabapentin for off-label use". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (20): 1963–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0906126. PMID 19907043.

^ Johannessen SI, Ben-Menachem E (2006). "Management of focal-onset seizures: an update on drug treatment". Drugs. 66 (13): 1701–25. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666130-00004. PMID 16978035.

^ French JA, Kanner AM, Bautista J, Abou-Khalil B, Browne T, Harden CL, Theodore WH, Bazil C, Stern J, Schachter SC, Bergen D, Hirtz D, Montouris GD, Nespeca M, Gidal B, Marks WJ, Turk WR, Fischer JH, Bourgeois B, Wilner A, Faught RE, Sachdeo RC, Beydoun A, Glauser TA (May 2004). "Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs, I: Treatment of new-onset epilepsy: report of the TTA and QSS Subcommittees of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society". Epilepsia. 45 (5): 401–9. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.06204.x. PMID 15101821.

^ Enke O, New HA, New CH, Mathieson S, McLachlan AJ, Latimer J, Maher CG, Lin CC (July 2018). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CMAJ. 190 (26): E786–E793. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171333. PMC 6028270. PMID 29970367.

^ Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, AlAmri R, Kamath S, Thabane L, Devereaux PJ, Bhandari M (August 2017). "Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLoS Medicine. 14 (8): e1002369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369. PMC 5557428. PMID 28809936.

^ Bar Ad V (September 2010). "Gabapentin for the treatment of cancer-related pain syndromes". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 5 (3): 174–8. doi:10.2174/157488710792007310. PMID 20482492.

^ Phillips TJ, Cherry CL, Cox S, Marshall SJ, Rice AS (December 2010). Pai, ed. "Pharmacological treatment of painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". PLOS One. 5 (12): e14433. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...514433P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014433. PMC 3010990. PMID 21203440.

^ Tran DQ, Duong S, Bertini P, Finlayson RJ (February 2010). "Treatment of complex regional pain syndrome: a review of the evidence". Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia = Journal Canadien d'Anesthesie. 57 (2): 149–66. doi:10.1007/s12630-009-9237-0. PMID 20054678.

^ Dauri M, Faria S, Gatti A, Celidonio L, Carpenedo R, Sabato AF (August 2009). "Gabapentin and pregabalin for the acute post-operative pain management. A systematic-narrative review of the recent clinical evidences". Current Drug Targets. 10 (8): 716–33. doi:10.2174/138945009788982513. hdl:2108/10507. PMID 19702520.

^ Hamilton TW, Strickland LH, Pandit HG (August 2016). "A Meta-Analysis on the Use of Gabapentinoids for the Treatment of Acute Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 98 (16): 1340–50. doi:10.2106/jbjs.15.01202. PMID 27535436.

^ Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS (September 2010). "The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain". Pain. 150 (3): 573–81. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. PMID 20705215.

^ Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, McNicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice AS, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M (February 2015). "Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (2): 162–73. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0. PMC 4493167. PMID 25575710.

^ Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P (June 2012). "The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines" (PDF). Headache. 52 (6): 930–45. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02185.x. PMID 22671714. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2016.

^ Linde M, Mulleners WM, Chronicle EP, McCrory DC (June 2013). "Gabapentin or pregabalin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD010609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010609. PMID 23797675.

^ Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB (June 2007). "The role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidence". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 27 (3): 263–72. doi:10.1097/jcp.0b013e318059361a. PMID 17502773.

^ Schatzberg AF, Cole JO, DeBattista C (2010). Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-1-58562-377-8. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016.

^ Goldberg JF, Harrow M (1999). Bipolar Disorders: Clinical Course and Outcome. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-88048-768-9. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL (February 2002). "The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues". Journal of Affective Disorders. 68 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. PMID 11869778.

^ McLean RJ, Gottlob I (August 2009). "The pharmacological treatment of nystagmus: a review". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 10 (11): 1805–16. doi:10.1517/14656560902978446. PMID 19601699.

^ Strupp M, Brandt T (July 2009). "Current treatment of vestibular, ocular motor disorders and nystagmus". Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders. 2 (4): 223–39. doi:10.1177/1756285609103120. PMC 3002631. PMID 21179531.

^ Toulis KA, Tzellos T, Kouvelas D, Goulis DG (February 2009). "Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinical Therapeutics. 31 (2): 221–35. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.02.006. PMID 19302896.

^ Cheema D, Coomarasamy A, El-Toukhy T (November 2007). "Non-hormonal therapy of post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms: a structured evidence-based review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 276 (5): 463–9. doi:10.1007/s00404-007-0390-9. PMID 17593379.

^ Rada G, Capurro D, Pantoja T, Corbalán J, Moreno G, Letelier LM, Vera C (September 2010). "Non-hormonal interventions for hot flushes in women with a history of breast cancer" (Submitted manuscript). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD004923. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004923.pub2. PMID 20824841.

^ ab Mack A (2003). "Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin" (PDF). Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 9 (6): 559–68. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. PMID 14664664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2010.

^ Muncie HL, Yasinian Y, Oge' L (November 2013). "Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome". American Family Physician. 88 (9): 589–95. PMID 24364635.

^ "VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of substance use disorders" (PDF). 31 December 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

^ Sood A, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, Croghan IT, Sood R, Vander Weg MW, Wong GY, Hays JT (February 2007). "Gabapentin for smoking cessation: a preliminary investigation of efficacy". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 9 (2): 291–8. doi:10.1080/14622200601080307. PMID 17365760.

^ Sood A, Ebbert JO, Wyatt KD, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Sood R, Hays JT (March 2010). "Gabapentin for smoking cessation". Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 12 (3): 300–4. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntp195. PMC 2825098. PMID 20081039.

^ Berger TG, Steinhoff M (June 2011). "Pruritus and renal failure". Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 30 (2): 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.sder.2011.04.005. PMC 3692272. PMID 21767770.

^ Anand S (March 2013). "Gabapentin for pruritus in palliative care". The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 30 (2): 192–6. doi:10.1177/1049909112445464. PMID 22556282.

^ Scott LJ (December 2012). "Gabapentin enacarbil: in patients with restless legs syndrome". CNS Drugs. 26 (12): 1073–83. doi:10.1007/s40263-012-0020-3. PMID 23179641.

^ Edinger JD (2013). Insomnia, an Issue of Sleep Medicine Clinics. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 339. ISBN 978-0-323-18872-2. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ Morin CM, Espie CA (2 February 2012). The Oxford Handbook of Sleep and Sleep Disorders. Oxford University Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-19-970442-2. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ Schneider SA, Deuschl G (January 2014). "The treatment of tremor". Neurotherapeutics. 11 (1): 128–38. doi:10.1007/s13311-013-0230-5. PMC 3899476. PMID 24142589.

^ Zesiewicz TA, Elble RJ, Louis ED, Gronseth GS, Ondo WG, Dewey RB, Okun MS, Sullivan KL, Weiner WJ (November 2011). "Evidence-based guideline update: treatment of essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology". Neurology. 77 (19): 1752–5. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318236f0fd. PMC 3208950. PMID 22013182.

^ Sadeghi R, Ondo WG (December 2010). "Pharmacological management of essential tremor". Drugs. 70 (17): 2215–28. doi:10.2165/11538180-000000000-00000. PMID 21080739.

^ Aazh H, El Refaie A, Humphriss R (December 2011). "Gabapentin for tinnitus: a systematic review". American Journal of Audiology. 20 (2): 151–8. doi:10.1044/1059-0889(2011/10-0041). PMID 21940981.

^ ab "Neurontin packaging insert" (pdf). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1 May 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

^ Aronson JK (4 March 2014). Side Effects of Drugs Annual: A worldwide yearly survey of new data in adverse drug reactions. Newnes. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-444-62636-3. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

^ American Psychiatric Association (2013-05-22). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition.: DSM 5. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. ISBN 9780890425572.

^ "www.accessdata.fda.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2014.

^ "Suicidal Behavior and Ideation and Antiepileptic Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 1 August 2009.

^ Patorno E, Bohn RL, Wahl PM, Avorn J, Patrick AR, Liu J, Schneeweiss S (April 2010). "Anticonvulsant medications and the risk of suicide, attempted suicide, or violent death". JAMA. 303 (14): 1401–9. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.410. PMID 20388896.

^ Gabapentin Official FDA information, side effects and uses Archived 27 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

^ ab Mersfelder TL, Nichols WH (March 2016). "Gabapentin: Abuse, Dependence, and Withdrawal". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 50 (3): 229–33. doi:10.1177/1060028015620800. PMID 26721643.

^ ab Bonnet U, Scherbaum N (February 2018). "[On the risk of dependence on gabapentinoids]". Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie (in German). 86 (2): 82–105. doi:10.1055/s-0043-122392. PMID 29179227.

^ "Important Notice: Gabapentin Becomes a Schedule 5 Controlled Substance in Kentucky" (PDF). Kentucky State Board of Pharmacy. March 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

^ R.C. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 677–8.

ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

^ abcdefghi Sills GJ (February 2006). "The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 6 (1): 108–13. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.003. PMID 16376147.

^ ab Benzon H, Rathmell JP, Wu CL, Turk DC, Argoff CE, Hurley RW (11 September 2013). Practical Management of Pain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-323-17080-2.

^ abc Stahl SM, Porreca F, Taylor CP, Cheung R, Thorpe AJ, Clair A (2013). "The diverse therapeutic actions of pregabalin: is a single mechanism responsible for several pharmacological activities?". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 34 (6): 332–9. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.001. PMID 23642658.

^ Zvejniece L, Vavers E, Svalbe B, Veinberg G, Rizhanova K, Liepins V, Kalvinsh I, Dambrova M (October 2015). "R-phenibut binds to the α2-δ subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels and exerts gabapentin-like anti-nociceptive effects". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 137: 23–9. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2015.07.014. PMID 26234470.

^ abc Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, Feltner D (February 2007). "Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (2): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006. PMID 17222465.

^ ab Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC (May 2007). "Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (5): 220–8. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. PMID 17403543.

^ abcdef Dickens D, Webb SD, Antonyuk S, Giannoudis A, Owen A, Rädisch S, Hasnain SS, Pirmohamed M (June 2013). "Transport of gabapentin by LAT1 (SLC7A5)". Biochemical Pharmacology. 85 (11): 1672–83. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.022. PMID 23567998.

^ del Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M (October 2008). "Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2". European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 35 (3): 161–74. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015. PMID 18656534.

^ abcdefghij Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, Chapel S, Janiczek N, Burger P (October 2010). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 49 (10): 661–9. doi:10.2165/11536200-000000000-00000. PMID 20818832.

^ abcde Agarwal P, Griffith A, Costantino HR, Vaish N (May 2010). "Gabapentin enacarbil - clinical efficacy in restless legs syndrome". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 6: 151–8. PMC 2874339. PMID 20505847.

^ Khansari M, Sohrabi M, Zamani F (January 2013). "The Useage of Opioids and their Adverse Effects in Gastrointestinal Practice: A Review". Middle East Journal of Digestive Diseases. 5 (1): 5–16. PMC 3990131. PMID 24829664.

^ abcd Cundy KC, Sastry S, Luo W, Zou J, Moors TL, Canafax DM (December 2008). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of XP13512, a novel transported prodrug of gabapentin". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 48 (12): 1378–88. Bibcode:1991JClP...31..928S. doi:10.1177/0091270008322909. PMID 18827074.

^ ab Geldenhuys WJ, Mohammad AS, Adkins CE, Lockman PR (2015). "Molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier permeation". Therapeutic Delivery. 6 (8): 961–71. doi:10.4155/tde.15.32. PMC 4675962. PMID 26305616.

^ ab Müller CE (November 2009). "Prodrug approaches for enhancing the bioavailability of drugs with low solubility". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 6 (11): 2071–83. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200900114. PMID 19937841.

^ Boado RJ, Li JY, Nagaya M, Zhang C, Pardridge WM (October 1999). "Selective expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter at the blood-brain barrier". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (21): 12079–84. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612079B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079. PMC 18415. PMID 10518579.

^ Kaye AD (5 June 2017). Pharmacology, An Issue of Anesthesiology Clinics E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-323-52998-3.

^ Wyllie E, Cascino GD, Gidal BE, Goodkin HP (17 February 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

^ ab Yogeeswari P, Ragavendran JV, Sriram D (January 2006). "An update on GABA analogs for CNS drug discovery". Recent Patents on CNS Drug Discovery. 1 (1): 113–8. doi:10.2174/157488906775245291. PMID 18221197.

^ Rose MA, Kam PC (May 2002). "Gabapentin: pharmacology and its use in pain management". Anaesthesia. 57 (5): 451–62. doi:10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02399.x. PMID 11966555.

^ Wheless JW, Willmore J, Brumback RA (2009). Advanced Therapy in Epilepsy. PMPH-USA. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-1-60795-004-2.

^ Levandovskiy IA, Sharapa DI, Shamota TV, Rodionov VN, Shubina TE (February 2011). "Conformationally restricted GABA analogs: from rigid carbocycles to cage hydrocarbons". Future Medicinal Chemistry. 3 (2): 223–41. doi:10.4155/fmc.10.287. PMID 21428817.

^ William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 1737–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

^ Johnson DS, Li JJ (26 February 2013). The Art of Drug Synthesis. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 13–. ISBN 978-1-118-67846-6.

^ "Drug Profile: Gabapentin". Adis Insight.

^ Li JJ (2014). Blockbuster Drugs: The Rise and Fall of the Pharmaceutical Industry. OUP USA. pp. 158–. ISBN 978-0-19-973768-0.

^ Irving G (September 2012). "Once-daily gastroretentive gabapentin for the management of postherpetic neuralgia: an update for clinicians". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 3 (5): 211–8. doi:10.1177/2040622312452905. PMC 3539268. PMID 23342236.

^ Reed D (2 March 2012). The Other End of the Stethoscope: The Physician's Perspective on the Health Care Crisis. AuthorHouse. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-1-4685-4410-7.

^ Orrange S (31 May 2013). "Yabba Dabba Gabapentin: Are Gralise and Horizant Worth the Cost?". GoodRx, Inc.

^ "Gabapentin controlled release - Depomed". Adis Insight.

^ Jeffrey, Susan. "FDA Approves Gabapentin Enacarbil for Postherpetic Neuralgia". Medscape.

^ "Warner–Lambert to pay $430 million to resolve criminal & civil health care liability relating to off-label promotion" (Press release). Department of Justice. 13 May 2004. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

^ Mathew NT, Rapoport A, Saper J, Magnus L, Klapper J, Ramadan N, Stacey B, Tepper S (February 2001). "Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis". Headache. 41 (2): 119–28. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.111006119.x. PMID 11251695.

^ ab Mack A (2003). "Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin" (PDF). Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 9 (6): 559–68. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. PMID 14664664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2010.

^ Pfizer Neurontin Label, Revised: 5/2013 Archived 10 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 August 2014

^ Reinares M, Rosa AR, Franco C, Goikolea JM, Fountoulakis K, Siamouli M, Gonda X, Frangou S, Vieta E (March 2013). "A systematic review on the role of anticonvulsants in the treatment of acute bipolar depression". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (2): 485–96. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000491. PMID 22575611.

^ ab Berkrot B (25 March 2010). "US jury's Neurontin ruling to cost Pfizer $141 mln". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015.

^ "Pfizer faces $142M in damages for drug fraud". Business Week. 25 March 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

^ Van Voris B, Lawrence J (26 March 2010). "Pfizer Told to Pay $142.1 Million for Neurontin Marketing Fraud". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

^ Kamp J (25 March 2010). "Jury Rules Against Pfizer in Marketing Case". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

^ Tansey B (14 May 2004). "Huge penalty in drug fraud, Pfizer settles felony case in Neurontin off-label promotion". San Francisco Chronicle. p. C-1. Archived from the original on 23 June 2006.

^ "Gralise Approval History". Drugs.com.

^ Baillie JK, Power I (January 2006). "The mechanism of action of gabapentin in neuropathic pain". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 7 (1): 33–9. PMID 16425669.

^ Jensen B, Regier LD, editors. RxFiles : Drug comparison charts. 7th ed. Saskatoon, SK: RxFiles, 2010; p.78

^ Kjellsson MC, Ouellet D, Corrigan B, Karlsson MO (October 2011). "Modeling sleep data for a new drug in development using markov mixed-effects models". Pharmaceutical Research. 28 (10): 2610–27. doi:10.1007/s11095-011-0490-x. PMID 21681607.

^ Landmark CJ, Johannessen SI (February 2008). "Modifications of antiepileptic drugs for improved tolerability and efficacy". Perspectives in Medicinal Chemistry. 2: 21–39. PMC 2746576. PMID 19787095.

^ "GlaxoSmithKline and XenoPort Receive FDA Approval for Horizant". GlaxoSmithKline and XenoPort, Inc.

^ Jeffrey S. "FDA Approves Gabapentin Enacarbil for Postherpetic Neuralgia". Medscape. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012.

^ Cundy KC, Branch R, Chernov-Rogan T, Dias T, Estrada T, Hold K, Koller K, Liu X, Mann A, Panuwat M, Raillard SP, Upadhyay S, Wu QQ, Xiang JN, Yan H, Zerangue N, Zhou CX, Barrett RW, Gallop MA (October 2004). "XP13512 [(+/-)-1-([(alpha-isobutanoyloxyethoxy)carbonyl] aminomethyl)-1-cyclohexane acetic acid], a novel gabapentin prodrug: I. Design, synthesis, enzymatic conversion to gabapentin, and transport by intestinal solute transporters". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 311 (1): 315–23. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.067934. PMID 15146028.

^ Cundy KC, Annamalai T, Bu L, De Vera J, Estrela J, Luo W, Shirsat P, Torneros A, Yao F, Zou J, Barrett RW, Gallop MA (October 2004). "XP13512 [(+/-)-1-([(alpha-isobutanoyloxyethoxy)carbonyl] aminomethyl)-1-cyclohexane acetic acid], a novel gabapentin prodrug: II. Improved oral bioavailability, dose proportionality, and colonic absorption compared with gabapentin in rats and monkeys". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 311 (1): 324–33. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.067959. PMID 15146029.

^ Oxford Textbook of Correctional Psychiatry. Robert L. Trestman, Kenneth L. Appelbaum, Jeffrey L. Metzner. Oxford University Press, Apr 9, 2015. p. 167.

ISBN 978-0199360574

^ Goodman CW, Brett AS (August 2017). "Gabapentin and Pregabalin for Pain – Is Increased Prescribing a Cause for Concern?". The New England Journal of Medicine. 377 (5): 411–414. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1704633. PMID 28767350.

^ Evoy KE, Morrison MD, Saklad SR (March 2017). "Abuse and Misuse of Pregabalin and Gabapentin". Drugs. 77 (4): 403–426. doi:10.1007/s40265-017-0700-x. PMID 28144823.

^ Vettorato E, Corletto F (September 2011). "Gabapentin as part of multi-modal analgesia in two cats suffering multiple injuries". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 38 (5): 518–20. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2011.00638.x. PMID 21831060.

^ van Haaften, Karen A.; Forsythe, Lauren R. Eichstadt; Stelow, Elizabeth A.; Bain, Melissa J. (15 November 2017). "Effects of a single preappointment dose of gabapentin on signs of stress in cats during transportation and veterinary examination". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 251 (10): 1175–81. doi:10.2460/javma.251.10.1175. PMID 29099247.

^ Forney B. "Gabapentin for Veterinary Use". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012.

External links

| Scholia has a topic profile for Gabapentin. |

- DrugBank: gabapentin

- Gabapentin information from MedlinePlus

"Gabapentin" PubMed Health. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)

"Suicidal Behavior and Ideation and Antiepileptic Drugs" U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

Neurontin collected news and commentary at The New York Times

"Gabapentin" Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.