Jaco Pastorius

Jaco Pastorius | |

|---|---|

Pastorius in concert, 1986 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | John Francis Pastorius III |

| Born | (1951-12-01)December 1, 1951 Norristown, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | September 21, 1987(1987-09-21) (aged 35) Fort Lauderdale, Florida, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, jazz fusion |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, producer |

| Instruments | Electric bass |

| Years active | 1964–1987 |

| Labels | Epic, Warner Bros., Columbia, ECM, CBS, Elektra |

| Associated acts | Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, Weather Report, Trio of Doom, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders, Albert Mangelsdorff, Al Di Meola |

| Website | jacopastorius.com |

John Francis Anthony "Jaco" Pastorius III (/ˈdʒɑːkoʊ pæˈstɔːriəs/, December 1, 1951 – September 21, 1987) was an American jazz bassist who was a member of Weather Report from 1976 to 1981. He worked with Pat Metheny, Joni Mitchell, and recorded albums as a solo artist and band leader.[1] His bass playing employed funk, lyrical solos, bass chords, and innovative harmonics. As of 2017, he is the only electric bassist of seven bassists inducted into the DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame,[2] and has been lauded as one of the best electric bassists of all time.[3][4]

Contents

1 Biography

1.1 Growing up in Fort Lauderdale

1.2 Early career

1.3 Weather Report

1.4 Word of Mouth

1.5 Death

2 Stage presence and bass techniques

3 Equipment

3.1 Bass of Doom

3.2 Amplification and effects

4 Guest appearances

5 Awards and honors

6 Discography

7 See also

8 Notes

9 References

10 External links

Biography

Growing up in Fort Lauderdale

John Francis Pastorius was born December 1, 1951, in Norristown, Pennsylvania. He was the oldest of three boys born to Stephanie, his Finnish mother, and Jack Pastorius, a charismatic singer and jazz drummer who spent much of his time on the road. His family moved to Oakland Park in Fort Lauderdale when he was eight.[5]

Pastorius' nickname, "Jaco", became adopted, and was partially influenced by his love for sports as well as the umpire Jocko Conlan. In 1974, he began spelling it "Jaco" after it was misspelled by his neighbor, pianist Alex Darqui. His brother called him "Mowgli" after the wild boy in The Jungle Book because he was energetic and spent much of his time shirtless on the beach, climbing trees, running through the woods, and swimming in the ocean. He attended St. Clement's Catholic School in Wilton Manors and was an altar boy at St. Clement's Church. His confirmation name was Anthony, thus expanding his name to John Francis Anthony Pastorius. He was intensely competitive and excelled at baseball, basketball, and football.[5]

He played drums until he injured his wrist playing football when he was thirteen. The damage was severe enough to warrant corrective surgery and inhibited his ability to play the drums.[5]

Early career

By 1968–1969, at the age of 17, Pastorius had begun to appreciate jazz and had saved enough money to buy an upright bass. Its deep, mellow tone appealed to him, though it strained his finances. He had difficulty maintaining the instrument, which he attributed to the humidity in Florida. When he woke one day to find it had cracked, he traded it for a 1962 Fender Jazz Bass.[6]

In his teens he played bass guitar for Wayne Cochran and the C.C. Riders.[7]

Pastorius on November 27, 1977

In the early 1970s, Pastorius taught bass at the University of Miami, where he befriended jazz guitarist Pat Metheny, who was also on the faculty. With Paul Bley, Pastorius and Metheny recorded an album, later titled Jaco (Improvising Artists, 1974).[8] Pastorius then played on Metheny's debut album, Bright Size Life (ECM, 1976).[9] He recorded his debut solo album, Jaco Pastorius (Epic, 1976) with Michael Brecker, Randy Brecker, Herbie Hancock, Hubert Laws, Pat Metheny, Sam & Dave, David Sanborn, and Wayne Shorter.[10]

Weather Report

Before recording his debut album, Pastorius attended a concert in Miami by the jazz fusion band Weather Report. After the concert, he approached keyboardist Joe Zawinul, who led the band. As was his habit, he introduced himself by saying, "I'm John Francis Pastorius III. I'm the greatest bass player in the world."[11] Zawinul admired his brashness and asked for a demo tape. After listening to the tape, Zawinul realized that Pastorius had considerable skill.[5] They corresponded, and Pastorius sent Zawinul a rough mix of his solo album.

After bassist Alphonso Johnson left Weather Report, Zawinul asked Pastorius to join the band. Pastorius made his band debut on the album Black Market (Columbia, 1976), in which he shared the bass chair with Johnson. Pastorius was fully established as sole band bass player for the recording of Heavy Weather (Columbia, 1977), which contained the Grammy-nominated hit "Birdland".[7]

During his time with Weather Report, Pastorius began abusing alcohol and illegal drugs,[5][12] which exacerbated existing mental problems and led to erratic behavior.[13] He left Weather Report in 1982 due to clashes with tour commitments for his other projects, plus a growing dissatisfaction with Zawinul's synthesized and orchestrated approach to the band's music.[5]

Word of Mouth

Pastorius in New York City with Jorma Kaukonen behind him, left, March 1986

Warner Bros. signed Pastorius to a favorable contract in the late 1970s based on his groundbreaking skill and his star quality, which they hoped would lead to large sales. He used this contract to set up his Word of Mouth big band[5] which consisted of Chuck Findley on trumpet, Howard Johnson on tuba, Wayne Shorter, Michael Brecker, and Tom Scott on reeds, Toots Thielemans on harmonica, Peter Erskine and Jack DeJohnette on drums, and Don Alias on percussion. This was the group that recorded his second solo album, Word of Mouth (Warner Bros., 1981).[14]

In 1982, Pastorius toured with Word of Mouth as a 21-piece big band. While in Japan, to the alarm of his band members, he shaved his head, painted his face black, and threw his bass guitar into Hiroshima Bay.[5] He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in late 1982 after the tour.[15][16] Pastorius had shown signs of bipolar disorder before his diagnosis, but these signs were dismissed as eccentricities, character flaws, and by Pastorius himself as a normal part of his freewheeling personality.[17][18]

Despite attention in the press, Word of Mouth sold poorly. Warner Bros. was unimpressed by the demo tapes from Holiday for Pans.[5] Pastorius released a third album, Invitation (1983), a live recording from the Word of Mouth tour of Japan. As alcohol and drug problems dominated his life, he had trouble finding work, finding people who would tolerate his shenanigans, and he wound up homeless. In 1985, while filming an instructional video, Pastorius told the interviewer, Jerry Jemmott, that although he had been praised often for his ability, he wished that someone would give him a job.[5]

Death

Pastorius developed a self-destructive habit of provoking bar fights and allowing himself to be beaten up.[5] After sneaking onstage at a Carlos Santana concert on September 11, 1987 and being ejected from the premises, he made his way to the Midnight Bottle Club in Wilton Manors, Florida.[19] After reportedly kicking in a glass door, having been refused entrance to the club, he was in a violent confrontation with Luc Havan, the club's manager who was a martial arts expert.[20] Pastorius was hospitalized for multiple facial fractures and injuries to his right eye and left arm, and fell into a coma.[21] There were encouraging signs that he would come out of the coma and recover, but they soon faded. A brain hemorrhage a few days later led to brain death. He was taken off life support and died on September 21, 1987 at the age of 35 at Broward General Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale.[19]

Luc Havan faced a charge of second-degree murder. He pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to twenty-two months in prison and five years' probation. After serving four months in prison, he was paroled for good behavior.[22]

Stage presence and bass techniques

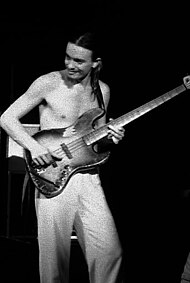

Pastorius demonstrating his harmonics, placing his bass guitar on the floor

Until about 1970, most jazz musicians played the acoustic, upright bass, also known as the double bass. Bassists remained in the background with the drummer, forming the rhythm section, while the saxophonist, trumpeter, or vocalist handled the melody and led the band. Pastorius had other ideas for the bass player. He played an electric bass from which he had removed the frets. He played fast and loud, sang, and did flips. He spread powder on the stage so he could dance like James Brown. He joked around and talked to the crowd. A self-described Florida beach bum, he often went barefoot and shirtless. He was tall, lean, and strong, and for someone who played sports the nickname "Jocko" fit. His thumbs were double jointed and his fingers were long and thin.[5][11]

After being taught about artificial harmonics, he added them to his technique and repertoire. Natural harmonics, also known as open string harmonics, are played by lightly touching the string at a fret without pressing it to the fretboard, resulting in a note that rings somewhat like a bell. Artificial harmonics, also called false harmonics, involve lightly touching a string with one finger, then using another finger to play the note,[5] simultaneously playing and stopping the note.[23] An often cited example is the introduction to "Birdland".

He was noted for virtuosic bass lines which combined Afro-Cuban rhythms, inspired by the likes of Cachao Lopez, with R&B to create 16th-note funk lines syncopated with ghost notes. He played these with a floating thumb technique on the right hand, anchoring on the bridge pickup while playing on the E and A strings and muting the E string with his thumb while playing on higher strings. Examples include "Come On, Come Over" from the album Jaco Pastorius and "The Chicken" from The Birthday Concert.

Equipment

Bass of Doom

Pastorius played a 1962 Fender Jazz Bass that he called the Bass of Doom. When he was 21, Jaco acquired the bass with its frets removed, or removed them himself (his recollections varied over the years), and sealed the fretboard with epoxy resin.[24][25]

One anecdote, as recounted by Allyn Robinson in an interview with Robert Sturrken on his "Nightlife and Music with the Maestro" program on WYLK Lake 94, claimed Jaco removed the frets only four hours before a gig with Wayne Cochran.

In 1986 the bass was repaired by luthiers Kevin Kaufman and Jim Hamilton, after it had been broken into many pieces.[26] After the repair Pastorius recorded a session with Mike Stern, then the bass was stolen from a park bench in Manhattan in 1986. It was found in a guitar shop in 2006, but the shop owner refused to give it up. The Pastorius family enlisted lawyers to help but nearly went bankrupt in 2010. Robert Trujillo, bass guitarist for Metallica, considered Jaco Pastorius to be one of his heroes, and he felt that the family ought to have the bass. Trujillo helped pay to have it returned to them.[27][28]

Amplification and effects

Pastorius used the "Variamp" EQ (equalization) controls on his two Acoustic 360 amplifiers[29] (made by the Acoustic Control Corporation of Van Nuys, California) to boost the midrange frequencies, thus accentuating the natural growling tone of his fretless passive Fender Jazz Bass and roundwound string combination. He also controlled his tone color with a rackmount MXR digital delay unit that fed a second Acoustic amp rig.

During the final three years of his life he used Hartke cabinets because of the character of aluminum speaker cones (as opposed to paper speaker cones). These provided a bright, clear sound. He typically used the delay in a chorus-like mode, providing a shimmering stereo doubling effect. He often used the fuzz control built into the Acoustic 360. For the bass solo "Slang/Third Stone From the Sun" on Weather Report's live album 8:30 (1979), Pastorius used the MXR digital delay to layer and loop a chordal figure and then soloed over it; the same technique, with a looped bass riff, can be heard during his solo on the Joni Mitchell concert video Shadows and Light.

Guest appearances

Pastorius appeared as a guest on many albums by other artists, including Ian Hunter of Mott the Hoople, on All American Alien Boy in 1976. He can be heard on Airto Moreira's album I'm Fine, How Are You? (1977). His signature sound is prominent on Flora Purim's Everyday Everynight (1978), on which he played the bass melody for a Michel Colombier composition entitled "The Hope", and performed bass and vocals on one of his own compositions, entitled "Las Olas". Other recordings included Joni Mitchell's Hejira and Al Di Meola’s Land of the Midnight Sun, both released in 1976. Near the end of his career, he worked often with guitarist Mike Stern, guitarist Biréli Lagrène, and drummer Brian Melvin.

Awards and honors

Pastorius received two Grammy Award nominations in 1977 for his self-titled debut album: one for Best Jazz Performance by a Group and one for Best Jazz Performance by a Soloist ("Donna Lee").[30] In 1978, he received a Grammy nomination for Best Jazz Performance by a Soloist for his work on Weather Report's album Heavy Weather.[31]

Bass Player magazine gave him second place on a list of the one hundred greatest bass players of all time, behind James Jamerson.[32] After his death in 1987, he was voted, by readers of Down Beat magazine, to its Hall of Fame, joining bassists Jimmy Blanton, Ray Brown, Ron Carter, Charles Mingus, Charlie Haden, and Milt Hinton.[33]

Many musicians have composed songs in his honour, such as Pat Metheny's "Jaco" on the album Pat Metheny Group (1978)[34] and "Mr. Pastorius" by Marcus Miller on Miles Davis's album Amandla. Others who have dedicated compositions to him include Randy Brecker, Eliane Elias, Chuck Loeb, John McLaughlin, Bob Moses, Ana Popović, Dave Samuels, and the Yellowjackets.[5]

On December 2, 2007, the day after his birthday, a concert called "20th Anniversary Tribute to Jaco Pastorius" was held at Broward Center for the Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with performances by the Jaco Pastorius Big Band and appearances by Randy Brecker, Dave Bargeron, Peter Erskine, Jimmy Haslip, Bob Mintzer, Gerald Veasley, Pastorius's sons John and Julius Pastorius, Pastorius's daughter Mary Pastorius, Ira Sullivan, Bobby Thomas Jr., and Dana Paul. Almost twenty years after his death, Fender released the Jaco Pastorius Jazz Bass, a fretless instrument in its Artist Series.

He has been called "arguably the most important and ground-breaking electric bassist in history" and "perhaps the most influential electric bassist today".[35][36]

William C. Banfield, director of Africana Studies, Music and Society at Berklee College, described Pastorius as one of the few original American virtuosos who defined a musical movement, in addition to Jimi Hendrix, Louis Armstrong, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Christian, Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, Sarah Vaughan, Bill Evans, Charles Mingus and Wes Montgomery.[37]

Discography

See also

Jaco, a 2014 documentary- List of jazz bassists

Notes

^ Harrison, Angus (2015-03-06). "Jaco Pastorius Is the Most Important Musician You Might Have Never Heard Of | NOISEY". Noisey.vice.com. Retrieved 2016-01-14..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "DownBeat Archives". downbeat.com. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

^ Stone, Rolling (March 31, 2011). "Readers Poll: Top 10 Bassists of All Time". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

^ https://indianapublicmedia.org/nightlights/greatest-bass-player-world-jaco-pastorius/

^ abcdefghijklmn Milkowski, Bill (1995). Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius, "The World's Greatest Bass Player". San Francisco: Miller Freeman. ISBN 0-87930-361-1.

^ Bob Bobbing (2007), Jaco and the upright bass; Jaco Pastorius official website biography

^ ab "Jaco Pastorius Opens Up in His First Guitar World Interview From 1983". Guitar World. 28 August 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ Yanow, Scott. "Jaco". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ Ginell, Richard S. "Bright Size Life". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ "Jaco Pastorius Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

^ ab Trjullo, Robert (Producer) (2015). Jaco (DVD). Los Angeles: Slang East/West.

^ Flynn

^ Tom Moon 1987

^ Yanow, Scott. "Word of Mouth". AllMusic. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

^ "'Jaco,' a Documentary About the Jazz Musician Jaco Pastorius". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

^ "Metallica's Robert Trujillo On His Hero, Jaco Pastorius". Retrieved September 22, 2018.

^ Milkowski 2005

^ Grayson, 2003

^ ab Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist (2nd ed.). New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0-7434-6330-7.

^ Stratton, Jeff (30 November 2006). "Jaco Incorporated". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

^ Krause, Renee (16 September 1987). "Noted Musician Listed As Critical After Altercation". Sun Sentinel. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

^ Zimmerman, Lee (1 December 2011). "Happy Birthday, Jaco Pastorius!". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

^ Stix, John (2000). Bass Secrets: Where Today's Bass Stylists Get to the Bottom Line. Cherry Lane Music Company. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-1-57560-219-6. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

^ "The Life of Jaco". jacopastorius.com. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

^ Duffy, Mike (21 June 2010). "Metallica's Trujillo Rescues Jaco Pastorius' Bass of Doom". Fender News. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

^ "Remembering Jaco Pastorius: A Tribute to His Favorite Gear". reverb.com. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

^ Johnson, Kevin (31 May 2010). "Robert Trujillo Helps Pastorius Family Reclaim Jaco's "Bass of Doom"". No Treble. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

^ Bradman, E.E. (15 January 2016). "Jaco! The Story Behind Robert Trujillo's Intense New Documentary". BassPlayer.com. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

^ "Acoustic 360 amplifiers". Acoustic.homeunix.net. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2011.

^ "Grammy Awards 1977", Awards and Shows, retrieved July 1, 2013

^ "Grammy Awards 1978", Awards and Shows, retrieved July 1, 2013

^ "The 100 Greatest Bass Players of All Time". BassPlayer.com. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

^ "DownBeat Hall of Fame", DownBeat, retrieved July 1, 2013

^ Metheny, Pat (2000). Pat Metheny Song Book (Songbook ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corp. p. 439. ISBN 0-634-00796-3.

^ Belew, Adrian; Di Meloa, Al; Fripp, Robert; McLaughlin, John (1986). Casabona, Helen, ed. New directions in modern guitar. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 0881884235.

^ Starr, Eric; Starr, Nelson (2008). Everything Bass Guitar Book. Holbrook, MA: F+W Media. ISBN 9781605502014.

^ Banfield, William C. (2010). Cultural codes : Makings of a Black Music Philosophy. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780810872868.

References

"Jacopastorius.co.uk". Jacopastorius.co.uk. Retrieved June 27, 2007.

"Jaco Pastorius: 20 Years Later". NPR. Retrieved March 4, 2008.

United Press (September 22, 1987). "Jazz Musician Jaco Pastorius Dies". JoniMitchell.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

Tom Moon (September 20, 1987). "Dark Days for a Jazz Genius". Miami Herald. JoniMitchell.com. Retrieved June 4, 2009.

Cole, George (2005). The Last Miles: The Music of Miles Davis, 1980–1991. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-03260-0.

Currin, Grayson (August 6, 2003). "Continuum". IndyWeek.com. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

Metheny, Pat (2000). "The Life and Music of Jaco Pastorious". Liner Notes to Jaco's eponymous debut album. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

Miller, Marcus (2002). "Perspectives on Jaco". JacoPastorius.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

Milkowsi, Bill (1984). "Bass Revolutionary: Jaco Pastorius Interview". Guitar Player (August 1984).

Prasad, Anil (1997). "Joe Zawinul, Man of the people". Innerviews. Archived from the original on June 15, 2009. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

Rosen, Steve (1978). "Portrait of Jaco". JacoPastorius.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

Salloum, I.M.; Thase, M.E. (2000). "Impact of substance abuse on the course and treatment of bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 2 (3 Pt 2): 269–80. doi:10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20308.x. PMID 11249805.

External links

Jaco Pastorius – official site

Jaco Pastorius at Find a Grave

Pastorius family site- Jaco Pastorius 1978 radio interview

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jaco Pastorius. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Jaco Pastorius |