Treaty of Georgievsk

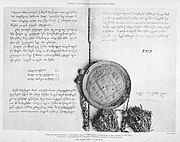

A photograph of the Georgian version of the Treaty of Georgievsk with Heraclius II's signature and seal, c. 1913 | |

| Signed | July 24, 1783 |

|---|---|

| Location | Georgiyevsk, Russian Empire |

| Sealed | 1784 |

| Effective | 1784 |

| Signatories | Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti and the Russian Empire |

The Treaty of Georgievsk (Russian: Георгиевский трактат, Georgievskiy traktat; Georgian: გეორგიევსკის ტრაქტატი, georgievskis trakt'at'i) was a bilateral treaty concluded between the Russian Empire and the east Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti on July 24, 1783.[1] The treaty established eastern Georgia as a protectorate of Russia, which guaranteed its territorial integrity and the continuation of its reigning Bagrationi dynasty in return for prerogatives in the conduct of Georgian foreign affairs.[2] By this, eastern Georgia abjured any form of dependence on Persia (who had been its suzerain for centuries) or another power, and every new Georgian monarch of Kartli-Kakheti would require the confirmation and investiture of the Russian tsar.

Contents

1 Terms

2 Aftermath

3 Legacy

4 References

5 Sources

6 Further reading

7 External links

Terms

Under articles I, II, IV, VI and VII of the treaty's terms, Russia's empress became the official and sole suzerain of Kartli-Kakheti's rulers, guaranteeing the Georgians’ internal sovereignty and territorial integrity, and promising to "regard their enemies as Her enemies" [3]

Each of the Georgian kingdom's tsars would henceforth be obliged to swear allegiance to Russia's emperors, to support Russia in war, and to have no diplomatic communications with other nations without Russia's prior consent.

Given Georgia's history of invasions from the south, an alliance with Russia may have been seen as the only way to discourage or resist Persian and Ottoman aggression, while also establishing a link to Western Europe.[2] In the past, Georgian rulers had not only accepted formal domination by Turkish and Persian emperors, but had also often converted to Islam, and sojourned at their capitals. Thus it was neither a break with Georgian tradition nor a unique capitulation of independence for Kartli-Kakheti to trade vassalage for peace with a powerful neighbor.[2] Though Russia was culturally alien,[4] in the treaty's preamble and article VIII the bond of Orthodox Christianity between Georgians and Russians was acknowledged, which tied the two, and Georgia's primate, the Catholicos, became Russia's eighth permanent archbishop and a member of Russia's Holy Synod.

@media all and (max-width:720px){.mw-parser-output .tmulti>.thumbinner{width:100%!important;max-width:none!important}.mw-parser-output .tmulti .tsingle{float:none!important;max-width:none!important;width:100%!important;text-align:center}}

Other treaty provisions included mutual guarantees of an open border between the two realms for travelers, emigrants and merchants (articles 10, 11), while Russia undertook "to leave the power for internal administration, law and order, and the collection of taxes [under the] complete will and use of His Serene Highness the Tsar, forbidding [Her Majesty’s] Military and Civil Authorities to intervene in any [domestic laws or commands]".

(article VI).[3] Article III created an investiture ceremony whereby the Georgian kings of Kartli-Kakheti, upon swearing fealty to Russia's emperors, would receive the royal regalia.[citation needed]

The treaty was negotiated on behalf of Russia by Lieutenant-General Pavel Potemkin, commander of Russia's troops in Astrakhan and a delegate and cousin of General Prince Grigori Alexandrovich Potemkin, who was the official Russian plenipotentiary. Kartli-Kakheti's official delegation consisted of a Kartlian and a Kakhetian, both of high rank: Ioane, Prince of Mukhrani, (referred to in the Russian version of the treaty as "Prince Ivan Konstantinovich Bagration"), Constable of the Left-Hand Army and son-in-law of the Georgian king, [1] and Adjutant-General Garsevan Chavchavadze, Governor of Kazakhi (aka Prince Garsevan Revazovich Chavchavadze, member of a Kakhetian princely family of the third rank, vassals of the Abashidze princes). [2] These emissaries officially signed the treaty at the fortress of Georgievsk in the North Caucasus on July 24, 1783.[citation needed] The Georgian King Erekle II and the Empress Catherine the Great then formally ratified it in 1784.[citation needed]

Aftermath

Entrance of the Russian troops in Tiflis on November 26, 1799. A painting by Franz Roubaud, 1886.

The Caucasian states and territories in 1799.

The results of the Treaty of Georgievsk proved disappointing for the Georgians.[2] King Erekle's adherence to it prompted Persia's new ruler, Agha Mohammad Khan, who had sent several ultimatums, to invade, as he sought to re-establish Persia's traditional suzerainty over the region.[5] Russia did nothing to help the Georgians during the disastrous Battle of Krtsanisi in 1795, which left Tbilisi sacked and Georgia ravaged (including the west Georgian kingdom of Imereti, ruled by Erekle II's grandson, King Solomon II). Belatedly, Catherine declared war on Persia and sent an army to Transcaucasia. But her death shortly thereafter (November 1796) put an end to Russia's Persian Expedition of 1796, as her successor, Paul, turned to other strategic objectives. Persia's Shahanshah next contemplated the removal of the Christian population from eastern Georgia and eastern Armenia, launching the campaign from Karabagh. His goal was frustrated not by Russian resistance, but by a Persian assassin in 1797.[citation needed]

On January 14, 1798, King Erekle II was succeeded on the throne by his eldest son, George XII (1746–1800) who, on February 22, 1799, recognized his own eldest son, Tsarevich David (Davit Bagrationi-batonishvili), 1767–1819, as official heir apparent. In the same year Russian troops were stationed in Kartli-Kakheti. Pursuant to article VI of the treaty, Emperor Paul confirmed David's claim to reign as the next king on April 18, 1799. But strife broke out among King George's many sons and those of his late father over the throne, Erekle II having changed the succession order at the behest of his third wife, Queen Darejan Dadiani, to favor the accession of younger brothers of future kings over their own sons. The resulting dynastic upheaval prompted King George to secretly invite Paul I to invade Kartli-Kakheti, to subdue the Bagratid princes, and to govern the kingdom from St. Petersburg, on the condition that George and his descendants be allowed to continue to reign nominally – in effect, offering to mediatize the Bagratid dynasty under the Romanov emperors.[6] Continued pressure from Persia, also prompted George XII's request for Russian intervention.[7]

Paul tentatively accepted this offer, but before negotiations could be finalized changed his mind and issued a decree on December 18, 1800 annexing Kartli-Kakheti to Russia and deposing the Bagratids.[8] Paul himself died shortly thereafter. It is said that his successor, Emperor Alexander I, considered retracting the annexation in favor of a Bagratid heir, but being unable to identify one likely to retain the crown, on September 12, 1801 Alexander proceeded to confirm annexation.[8] Meanwhile, King George had died on December 28, 1800, before learning that he had lost his throne. By the following April, Russian troops took control of the country's administration and in February 1803 Tsarevich David Bagrationi was escorted by Russian troops from Tbilisi to St. Petersburg. He was pensioned, joined the Russian Senate, and retained his royal style until May 6, 1833 when he was demoted from tsarevich (the Russian equivalent of batonishvili) to "prince" (knyaz), along with other members of the deposed dynasty, following an abortive uprising in Georgia led by David's uncle, Prince Alexandre Bagrationi.[citation needed]

The Russians then ended the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813 with a victory. By the Treaty of Gulistan (1813), Qajar Persia was forced to officially cede eastern Georgia to the Russian Empire.[9]

Paul's annexation of east Georgia and exile of the Bagratids remain controversial: Soviet historians would later maintain that the treaty was an act of "brotherhood of the Russian and Georgian peoples" that justified annexation to protect Georgia both from its historical foreign persecutors and its "decadent" native dynasty. Nonetheless, no bilateral amendment had been ratified altering article VI sections 2 and 3 of the 1784 treaty, which obligated the Russian emperor "to preserve His Serene Highness Tsar Irakli Teimurazovich and the Heirs and descendants to his House, uninterrupted on the Throne of the Kingdoms of Kartli and Kakheti...forbidding [Her Majesty’s] Military and Civil Authorities to intervene in any [domestic laws or commands]."[3]

Legacy

A 1790 Russian medal commemorating the treaty.

A 1983 Soviet stamp commemorating the 200-years anniversary of the treaty and celebrating it as "the first manifesto of the friendship and brotherhood between the Russian and Georgian peoples."

Ironically, that clause of the treaty would also be recalled during obscure late 20th century debates about restoration of the Russian monarchy.[10] In 1948, Vladimir Kirillovich Romanov, (1917–1992), pretender to Russia's throne, married Princess Leonida Georgievna Bagration-Moukhranskaya, (born 1914), a descendant of the Mukhranbatoni who negotiated the 1783 treaty, and thus a member of the once royal House of Bagrationi. The marriage produced an only child, Maria Vladimirovna, (born 1956), who has taken up her father's claim as Russia's de jure monarch. She and her son, George (born of her former marriage to Prince Franz Wilhelm of Prussia), have pretended to the Romanovs’ old grand ducal title. Her supporters argue that her father's marriage to Leonida, alone among those contracted by Romanov males in exile since 1917, complied with the Romanov house law that required marriage to a princess of a "royal or ruling family" in order for descendants to claim the throne.[10] That law also provided that upon extinction of all male dynasts, female Romanovs born of dynastic mothers become eligible to inherit the crown.[10] Based on this rationale, Maria purports to have the strongest legal claim to the Russian throne in the event that Russia ever restores its monarchy.[10]

Critics deny that Princess Leonida could be reckoned of royal rank by Romanov standards (the title of prince was one of nobility, not dynasty in Russia, except in the imperial family).[10] They point out that the Bagration-Mukhranskys were demoted from dynastic status and incorporated into Russia's ordinary nobility by 1833: Though the princess descended patrilineally from a dynasty that had ruled as kings in Armenia and Georgia since the Middle Ages, it had been reduced to the status of Russian nobility for over a century prior to the Russian Revolution. Leonida's branch of the Bagratids, although genealogically senior, had not been regnant in the male line as kings of Georgia since 1505.[11] Members of the family accepted court appointments under Russia's emperors incompatible with claims to dynastic dignity. Moreover, when an imperial Romanov princess wed Prince Constantine Bagration-Mukhransky in 1911, the marriage was officially deemed non-dynastic by Nicholas II,[12] and the bride, Tatiana Konstantinova Romanova, was obliged to renounce her succession rights.

While these facts are admitted, it is counter-argued that the demotion of the Bagratids, including the Mukhrani branch, violated the Treaty of Georgievsk and therefore failed to legally deprive any Bagrationi of royal rank.[10] That fact, it is claimed, distinguishes Leonida from princesses of other once-sovereign families of the Russian Empire who married Romanovs. Nonetheless, it was the agnatic seniority of the Mukhranbatoni’s descent from Georgia’s former kings, rather than the broken treaty, that Vladimir Kirilovich cited in a 1946 decree recognizing the Bagration-Mukhranskys as dynastic for marital purposes,[10] presumably so as to avoid repudiating the Russian Empire's annexation of Georgia.[citation needed]

The language of article VI guaranteed the Georgian throne not only to King Erekle II and his direct issue, but also embraced "the Heirs and descendants to his House".[3][10] On the other hand, article IX offered to extend no more than "the same privileges and advantages granted to the Russian nobility" to Georgia's princes and nobles.[3] Yet first on the list of families submitted to Russia to enjoy noble (not royal) status was that of the Mukhranbatoni. That list included twenty-one other princely families and a larger number of untitled nobles, most of whom were enrolled in Russia's nobility during the 19th century. The claims made on Maria's behalf have long embittered Romanov descendants who belong to the Romanov Family Association. Many of them descend matrilineally from noble Russian princesses, some of whose families were also of "dynastic" origin, but cannot claim that a Treaty of Georgievsk has "preserved" their "dynasticity".[citation needed]

the Russia–Georgia Friendship Monument, built for the bicentennial of the treaty

In 1983, the Soviet authorities celebrated the bicentennial of the Treaty of Georgievsk, provoking protests from anti-Soviet Georgian dissidents. In this period, several monuments to commemorate the treaty, among them the Russia–Georgia Friendship Monument along the Georgian Military Road. Georgia's underground Samizdat publication, Sakartvelo (საქართველო), dedicated a special issue to the event, emphasizing imperial Russia's disregard of the key agreements in the treaty. Underground political groups disseminated leaflets calling on Georgians to boycott the celebrations, and several young Georgian activists were arrested by the Soviet police.[13]

References

^ http://www.westminster.edu/staff/martinre/Treaty.html

^ abcd Anchabadze, George, Ph.D. History of Georgia. Georgia in the Beginning of Feudal Decomposition. (XVIII cen.). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

^ abcde Treaty of Georgievsk, 1783. PSRZ, vol. 22 (1830), pp. 1013–1017. Translated from the Russian by Russell E. Martin, Ph.D., Westminster College.

^ Perry 2006, pp. 108–109.

^ Kazemzadeh 1991, pp. 328–330.

^ Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh, 1980, "Burke's Royal Families of the World: Volume II Africa & the Middle East, page 59 .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-85011-029-7

^ Tsagareli, A (1902). Charters and other historical documents of the XVIII century regarding Georgia. pp. 287–288.

^ ab Encyclopædia Britannica, "Treaty of Georgievsk", 2008, retrieved 2008-6-16

^ Mikaberidze 2015, pp. 348–349.

^ abcdefgh Eilers, Marlene A., Queen Victoria's Descendants, Companion Volume. Rosvall Royal Books, Falköping, Sweden, 2004. pp. 79–84.

ISBN 91-630-5964-9.

^ Cyril Toumanoff, "The Fifteenth-Century Bagratides and the Institution of Collegial Sovereignty in Georgia". Traditio. Volume VII, Fordham University Press, New York 1949–1951, pp. 169–221

^ Frederiks, Baron V., Letter to Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, 1911-06-04, State Archives of the Russian Federation, Series 604, Inventory 1, File 2143, pages 58–59, retrieved 2008-11-04

^ (in Russian) Алексеева, Людмила (1983), Грузинское национальное движение. In: История Инакомыслия в СССР. Accessed on April 3, 2007.

Sources

Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles. The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.

Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

Perry, John R. (2006). Karim Khan Zand. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1851684359.

The Alexander Palace Time Machine: Some documents from the Reign of Catherine II[dead link]

(in English) Anchabadze, Dr. George. History of Georgia

- Buyers, Christopher. The Royal Ark, "Georgia"

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh. 1980 "Burke’s Royal Families of the World: Volume II Africa & the Middle East",

ISBN 0-85011-029-7

Further reading

David Marshall Lang: The Last Years of the Georgian Monarchy: 1658–1832. Columbia University Press, New York 1957.- Nikolas K. Gvosdev, Imperial policies and perspectives towards Georgia: 1760–1819. Macmillan [u.a.], Basingstoke [u.a.] 2000,

ISBN 0-312-22990-9. - "Traité conclu en 1783 entre Cathérine II. impératrice de Russie et Iracly II. roi de Géorgie". Recueil des lois russes; vol. XXI, No. 15835, Avec une préface de M. Paul Moriaud, Professeur de da Faculté de Droit de l’université de Genève, et commentaires de A. Okouméli, Genève 1909.

Zurab Avalov, Prisoedinenie Gruzii k Rossii. Montvid, S.-Peterburg 1906.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Georgievsk. |

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Treaty of Georgievsk |

- Treaty of Georgievsk (Translated from the Russian by Russell E. Martin, Westminster College)

The Portfolio; A Collection of State Papers, and other Document and Correspondence, Historical, Diplomatic, and Commercial, Vol. V, pp. 206–209. London: 1837