Hamelin

Hamelin Hameln | |

|---|---|

Panorama of Hamelin | |

Coat of arms | |

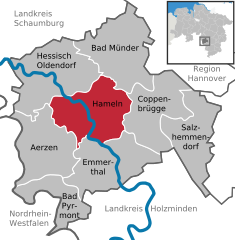

Location of Hamelin within Hamelin-Pyrmont district   | |

Hamelin Show map of Germany  Hamelin Show map of Lower Saxony | |

| Coordinates: 52°6′N 9°22′E / 52.100°N 9.367°E / 52.100; 9.367Coordinates: 52°6′N 9°22′E / 52.100°N 9.367°E / 52.100; 9.367 | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | Lower Saxony |

| District | Hamelin-Pyrmont |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Claudio Griese (CDU) |

| Area [1] | |

| • Total | 102.53 km2 (39.59 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 68 m (223 ft) |

| Population (2017-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 57,228 |

| • Density | 560/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 31785–89, 3250 |

| Dialling codes | 05151 |

| Vehicle registration | HM |

| Website | www.hameln.de |

Hamelin (/ˈhæməlɪn/; German: Hameln) is a town on the river Weser in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Hamelin-Pyrmont and has a population of roughly 56,000. Hamelin is best known for the tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

Contents

1 History

2 Geography

2.1 Subdivisions

3 Demographics

4 Attractions

4.1 Tale of the Pied Piper

5 Government

5.1 Town twinning

6 Media

7 British army presence

8 Notable people

9 See also

10 Gallery

11 References

12 External links

History

Hamelin started with a monastery, which was founded as early as 851 AD. A village grew in the neighbourhood and had become a town by the 12th century. The incident with the "Pied Piper" (see below) is said to have happened in 1284 and may be based on a true event, although somewhat different from the tale. In the 15th and 16th centuries Hamelin was a minor member of the Hanseatic League.

In June 1634, during the Thirty Years' War, Lothar Dietrich, Freiherr of Bönninghausen, a General with the Imperial Army, lost the Battle of Oldendorf to the Swedish General Kniphausen, after Hamelin had been besieged by the Swedish army.

The era of the town's greatest prosperity began in 1664, when Hamelin became a fortified border town of the Principality of Calenberg. In 1705, it became part of the newly created Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg, also called Hanover, when George Louis, Prince of Calenberg, later King George I of Great Britain, inherited the Principality of Lüneburg.

Hamelin was surrounded by four fortresses, which gave it the nickname "Gibraltar of the North". It was the most heavily fortified town in the Electorate of Hanover. The first fort (Fort George) was built between 1760 and 1763, the second (Fort Wilhelm) in 1774, a third in 1784, and the last (called Fort Luise) was built in 1806.

In 1808, Hamelin surrendered without fighting to Napoleon, after his victory at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt. Napoleon's forces subsequently pulled down the town's historic walls, guard towers and the three fortresses at the other side of the river Weser. In 1843, the people of Hamelin built a sightseeing tower on the Klüt Hill, out of the ruins of Fort George. This tower is called the Klütturm and is a popular sight for tourists.

In 1867 Hamelin became part of the Kingdom of Prussia, which annexed Hanover in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866.

During the Second World War, Hamelin prison was used for the detention of Social Democrats, Communists, and other political prisoners. Around 200 died here; more died in April 1945, when the Nazis sent the prisoners on long marches, fearing the Allied advance. Just after the war, Hamelin prison was used by British Occupation Forces for the detention of Germans accused of war crimes. Following conviction, around 200 of them were hanged there, including Irma Grese, Josef Kramer, and over a dozen of the perpetrators of the Stalag Luft III murders. The prison has since been turned into a hotel.[3] Executed war criminals were interred in the prison yard until it became full; further burials took place at the Am Wehl Cemetery in Hameln. In March 1954, the German authorities began exhuming the 91 bodies from the prison yard; they were reburied in individual graves in consecrated ground in Am Wehl Cemetery.[3]

The coat of arms (German: Wappen) of Hamelin depicts the St. Boniface Minster, the oldest church in the city.[4]

Geography

Subdivisions

Watershed of the river Weser.

- Afferde

- Hastenbeck

- Halvestorf

- Haverbeck

- Hilligsfeld (including Groß and Klein Hilligsfeld)

- Sünteltal (including Holtensen, Welliehausen and Unsen)

- Klein Berkel

- Tündern (pop. around 2,700),[5]

- Wehrbergen

- Rohrsen

- Welliehausen

Demographics

| Year | Inhabitants |

|---|---|

| 1689 | 2,398 |

| 1825 | 5,326 |

| 1905 | 21,385 |

| 1939 | 32,000 |

| 1968 | 48,787 |

| 2005 | 58,872 |

2018 { 72, 655'

Attractions

The Pied Piper leads the children out of Hamelin. Illustration by Kate Greenaway.

Christmas market in Hamelin.

Tale of the Pied Piper

The town is famous for the folk tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin (German: Der Rattenfänger von Hameln), a medieval story that tells of a tragedy that befell the town in the 13th century. The version written by the Brothers Grimm made it popular throughout the world; it is also the subject of well-known poems by Goethe and Robert Browning. In the summer every Sunday, the tale is performed by actors in the town centre.

Government

Town twinning

Hamelin is twinned with:

Quedlinburg, Germany

Quedlinburg, Germany

Torbay, United Kingdom

Torbay, United Kingdom

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France

Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France

Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, Poland

Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, Poland

Media

The Deister- und Weserzeitung, known as DeWeZet, publishes out of Hameln.

British army presence

Hamelin was home to several Royal Engineer units including 35 Engineer Regiment and 28 Amphibious Engineer Regiment until summer 2014, with many of the British families housed at Hastenbeck (Schlehenbusch) and Afferde. Also Royal Corps of Transport unit of 26 Bridging Regiment RCT, comprising 35 Sqn RCT and 40 Sqn RCT, until 1971.[6]

Notable people

Glückel of Hameln (1646–1724), Jewish businesswoman and diarist

Heinrich Bürger (1806–1858), German physicist, biologist and botanist

Oswald Freisler (1895–1939), lawyer and brother of Roland Freisler

Heinz Knoke (1923–1993), German officer of the Luftwaffe

Karl Philipp Moritz (1756–1793), German author

Peter the Wild Boy (found 1725), disabled boy- Saint Vicelinus (1086–1154), born in the town[7]

- Electronic group Funker Vogt

Johann Popken, founder of company that became Ulla Popken

Max Richter (born 1966) neo-classical composer

Ida Schreiter (1912–1948), concentration camp warden executed for war crimes

Friedrich Sertürner, (1783–1841) first to isolate morphine from opium (1822–1841)

Susan Stahnke (born 1967), German TV presenter

Friedrich Wilhelm von Reden (1752–1815), German pioneer in mining

Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918), Biblical scholar and orientalist

See also

- German Fairy Tale Route

- Metropolitan region Hannover-Braunschweig-Göttingen-Wolfsburg

Gallery

The Leisthaus, Hamelin

Jewish cemetery of Hamelin

The Golden Rat, on a footbridge over the River Weser in Hamelin

The Hochzeitshaus, the church's Glockenspiel plays the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin

References

^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2018 (4. Quartal)". DESTATIS. Archived from the original on 10 March 2019. Retrieved 10 March 2019..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ Landesamt für Statistik Niedersachsen, Tabelle 12411: Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes, Stand 31. Dezember 2017

^ ab "Post World War II hangings under British jurisdiction at Hameln Prison in Germany".

^ Start page at muenster-hameln.de

^ Official site Archived 2007-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-12-30. Retrieved 2012-12-25.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Vicelinus at the Catholic Encyclopedia

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hameln. |

Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Hameln. |

Official website (in German) (in English)

(in German) (in English)

Hameln Notgeld (emergency banknotes) depicting the story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin http://webgerman.com/Notgeld/Directory/H/Hameln.htm