High Plains (United States)

| High Plains | |

|---|---|

A buffalo wallow on the High Plains.[1] | |

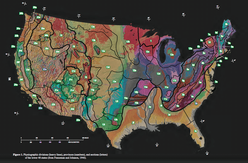

Physiographic regions of the United States. The High Plains region is the center yellow area designated 13d.[2] | |

| Floor elevation | 1,160–7,800 ft (350–2,380 m)[3] |

| Length | 800 mi (1,300 km) |

| Width | 400 mi (640 km) |

| Area | 174,000 sq mi (450,000 km2) [3] |

| Geography | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 39°N 102°W / 39°N 102°W / 39; -102Coordinates: 39°N 102°W / 39°N 102°W / 39; -102 |

The High Plains ecology region is designated by 25 on this map.

Childress County, Texas, June 1938.

The High Plains are a subregion of the Great Plains mostly in the Western United States, but also partly in the Midwest states of Nebraska, Kansas, and South Dakota, generally encompassing the western part of the Great Plains before the region reaches the Rocky Mountains. The High Plains are located in southeastern Wyoming, southwestern South Dakota, western Nebraska, eastern Colorado, western Kansas, eastern New Mexico, western Oklahoma, and south of the Texas Panhandle.[4] The southern region of the Western High Plains ecology region contains the geological formation known as Llano Estacado which can be seen from a short distance or on satellite maps.[5] From east to west, the High Plains rise in elevation from around 1,160 feet (350 m) to over 7,800 feet (2,400 m).[3]

Contents

1 Name

2 Geography and climate

3 Flora

4 Economy

5 Demographics

6 Major cities and towns

7 Gallery

8 See also

9 Notes

10 External links

Name

The term "Great Plains", for the region west of about the 96th or 98th meridian and east of the Rocky Mountains, was not generally used before the early 20th century. Nevin Fenneman's 1916 study, Physiographic Subdivision of the United States,[6] brought the term Great Plains into more widespread usage. Prior to 1916, the region was almost invariably called the High Plains, in contrast to the lower Prairie Plains of the Midwestern states.[7] Today the term "High Plains" is usually used for a subregion instead of the whole of the Great Plains.

Geography and climate

The High Plains has a "cold semi-arid" climate—Köppen BSk—receiving between 10–20 inches (250–510 mm) of precipitation annually.

Due to low moisture and high elevation, the High Plains commonly experiences wide ranges and extremes in temperature. The temperature range from day to night is usually 30 °F (17 °C), and 24-hour temperature shifts of 100 °F (56 °C) are possible, as evidenced by a weather event that occurred in Browning, Montana from January 23, 1916 to January 24, 1916, when the temperature fell from 44 to −56 °F (7 to −49 °C). This is the world record for the greatest temperature change in 24 hours.[8] The region is known for the steady, and sometimes intense, winds that prevail from the west. The winds add a considerable wind chill factor in the winter. The development of wind farms in the High Plains is one of the newest areas of economic development.

The High Plains are anomalously high in elevation. An explanation has recently been proposed to explain this high elevation. As the Farallon plate was subducted into the mantle beneath the region, water trapped in hydrous minerals in the descending slab was forced up into the lower crust above. Within the crust this water caused the hydration of dense garnet and other phases into lower density amphibole and mica minerals. The resulting increase in crustal volume raised the elevation about one mile.[9][10]

Flora

Typical plant communities of the region are shortgrass prairie, prickly pear cacti and scrub. Sagebrush steppe is also present, particularly in high and dry areas closer to the Rocky Mountains.

Economy

Agriculture in the forms of cattle ranching and the growing of wheat, corn and sunflowers is the primary economic activity in the region. The aridity of the region necessitates either dryland farming methods or irrigation; much water for irrigation is drawn from the underlying Ogallala Aquifer, which makes it possible to grow water-intensive crops such as corn, which the region's aridity would otherwise not support.[citation needed] Some areas of the High Plains have significant petroleum and natural gas deposits.

The combination of oil, natural gas, and wind energy along with plentiful underground water, has allowed some areas (such as West Texas) to sustain a range of economic activity, including occasional industry. For example, the ASARCO refinery in Amarillo, Texas has been in operation since 1924 due to the plentiful and inexpensive natural gas and water that are needed in metal ore refining.[citation needed]

Demographics

The High Plains has one of the lowest population densities of any region in the continental United States; Wyoming, for example, has the second lowest population density in the country after Alaska. In contrast to the rather low and stagnant population in the northern and western High Plains, cities in west Texas have shown sustained growth; Amarillo and Lubbock both have populations near or above 200,000 and continue to grow.[citation needed] Smaller towns, on the other hand, often struggle to sustain their population.

Major cities and towns

|

|

|

|

Gallery

High Plains in Oklahoma west of Guymon (2009)

Cimarron County near Boise City. (2009)

Grain silos are a common sight on the High Plains. (2009)

High Plains in Southeastern Colorado (2009)

The High Plains are broken in places by canyons, such as this one in Sabinoso Wilderness in New Mexico.

See also

- Dust storm

- Flora of the Great Plains (North America)

- Flora of the Plains-Midwest (United States)

- Great American Desert

- List of ecoregions in the United States (EPA)

- Llano Estacado

- North American Prairies Province

- Shortgrass prairie

- Steppe

Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands—Biome

Texas High Plains AVA, wine region in the Texas section of the High Plains- Tibetan Plateau

- Western short grasslands

- Wind power in Texas

Notes

^ Darton, Nelson Horatio (1920). Syracuse-Lakin folio, Kansas. Folios of the Geologic Atlas, No. 212: United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. p. 17 (plate 2)..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "Physiographic Regions". U.S. Department of the Interior. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

^ abc "USGS High Plains Aquifer WLMS". U.S. Department of the Interior. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-10-06.

^ File:Level III ecoregions, United States.png

^ "Shaded relief image of the Llano Estacado". Handbook of Texas: Llano Estacado.

^ Fenneman, Nevin M. (January 1917). "Physiographic Subdivision of the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 3 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.3.1.17. OCLC 43473694. PMC 1091163. PMID 16586678.

^ Brown, Ralph Hall (1948). Historical Geography of the United States. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. pp. 373–374. OCLC 186331193.

^ "Top Ten Montana Weather Events of the 20th Century". National Weather Service Unveils Montana's Top Ten Weather/Water/Climate Events of the 20th Century. National Weather Service. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

^ Why Are the High Plains So High? THECHERRYCREEKNEWS.COM, Mar 15, 2005 (2015?)

^ Jones, Craig H.; Mahan, Kevin H.; Butcher, Lesley A.; Levandowski, William B.; Farmer, G. Lang (2015). "Continental uplift through crustal hydration". Geology. 43 (4): 355–358. doi:10.1130/G36509.1.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for High Plains. |

High Plains Regional Climate Center High Plains climatological resources

High Plains information - U.S. Department of the Interior (with map)- Trains on the High Plains

- Texas counties map showing the ecoregion