Observable universe

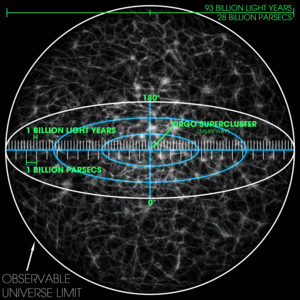

Visualization of the whole observable universe. The scale is such that the fine grains represent collections of large numbers of superclusters. The Virgo Supercluster—home of Milky Way—is marked at the center, but is too small to be seen. | |

| Diameter | 7026880000000000000♠8.8×1026 m (28.5 Gpc or 93 Gly)[1] |

|---|---|

| Volume | 7080400000000000000♠4×1080 m3[2] |

| Mass (ordinary matter) | 4.5 x 10 51 kg [3] |

| Density (of total energy) | 6973990000000000000♠9.9×10−27 kg/m3 (equivalent to 6 protons per cubic meter of space)[4] |

| Age | 7010137990000000000♠13.799±0.021 billion years[5] |

| Average temperature | 2.72548 K[6] |

| Contents |

|

The observable universe is a spherical region of the Universe comprising all matter that can be observed from Earth or its space-based telescopes and exploratory probes at the present time, because electromagnetic radiation from these objects has had time to reach the Solar System and Earth since the beginning of the cosmological expansion. There are at least 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe.[8][9] Assuming the Universe is isotropic, the distance to the edge of the observable universe is roughly the same in every direction. That is, the observable universe has a spherical volume (a ball) centered on the observer. Every location in the Universe has its own observable universe, which may or may not overlap with the one centered on Earth.

The word observable in this sense does not refer to the capability of modern technology to detect light or other information from an object, or whether there is anything to be detected. It refers to the physical limit created by the speed of light itself. Because no signals can travel faster than light, any object farther away from us than light could travel in the age of the Universe (estimated as of 2015[update] around 7010137990000000000♠13.799±0.021 billion years[5]) simply cannot be detected, as the signals could not have reached us yet. Sometimes astrophysicists distinguish between the visible universe, which includes only signals emitted since recombination (when hydrogen atoms were formed from protons and electrons and photons were emitted)—and the observable universe, which includes signals since the beginning of the cosmological expansion (the Big Bang in traditional physical cosmology, the end of the inflationary epoch in modern cosmology).

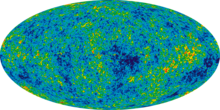

According to calculations, the current comoving distance—proper distance, which takes into account that the universe has expanded since the light was emitted—to particles from which the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR) was emitted, which represent the radius of the visible universe, is about 14.0 billion parsecs (about 45.7 billion light-years), while the comoving distance to the edge of the observable universe is about 14.3 billion parsecs (about 46.6 billion light-years)[10], about 2% larger. The radius of the observable universe is therefore estimated to be about 46.5 billion light-years[11][12] and its diameter about 28.5 gigaparsecs (93 billion light-years, 8.8×1023 kilometres or 5.5×1023 miles).[13] The total mass of ordinary matter in the universe can be calculated using the critical density and the diameter of the observable universe to be about 1.5 × 1053 kg.[14] In November 2018, astronomers reported that the extragalactic background light (EBL) amounted to 4 × 1084 photons.[15][16]

Since the expansion of the universe is known to accelerate and will become exponential in the future, the light emitted from all distant objects, past some time dependent on their current redshift, will never reach the Earth. In the future all currently observable objects will slowly freeze in time while emitting progressively redder and fainter light. For instance, objects with the current redshift z from 5 to 10 will remain observable for no more than 4–6 billion years. In addition, light emitted by objects currently situated beyond a certain comoving distance (currently about 19 billion parsecs) will never reach Earth.[17]

Contents

1 The universe versus the observable universe

2 Size

2.1 Misconceptions on its size

3 Large-scale structure

3.1 Walls, filaments, nodes, and voids

3.2 End of Greatness

3.3 Observations

3.4 Cosmography of Earth's cosmic neighborhood

4 Mass of ordinary matter

4.1 Estimates based on critical density

5 Matter content – number of atoms

6 Most distant objects

7 Horizons

8 See also

9 References

10 Further reading

11 External links

The universe versus the observable universe

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Physical cosmology | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| ||||

Early universe

| ||||

Expansion · Future

| ||||

Components · Structure

| ||||

Experiments

| ||||

| ||||

Subject history

| ||||

| ||||

Some parts of the universe are too far away for the light emitted since the Big Bang to have had enough time to reach Earth or its scientific space-based instruments, and so lie outside the observable universe. In the future, light from distant galaxies will have had more time to travel, so additional regions will become observable. However, due to Hubble's law, regions sufficiently distant from the Earth are expanding away from it faster than the speed of light (special relativity prevents nearby objects in the same local region from moving faster than the speed of light with respect to each other, but there is no such constraint for distant objects when the space between them is expanding; see uses of the proper distance for a discussion) and furthermore the expansion rate appears to be accelerating due to dark energy. Assuming dark energy remains constant (an unchanging cosmological constant), so that the expansion rate of the universe continues to accelerate, there is a "future visibility limit" beyond which objects will never enter our observable universe at any time in the infinite future, because light emitted by objects outside that limit would never reach the Earth. (A subtlety is that, because the Hubble parameter is decreasing with time, there can be cases where a galaxy that is receding from the Earth just a bit faster than light does emit a signal that reaches the Earth eventually.[12][18]) This future visibility limit is calculated at a comoving distance of 19 billion parsecs (62 billion light-years), assuming the universe will keep expanding forever, which implies the number of galaxies that we can ever theoretically observe in the infinite future (leaving aside the issue that some may be impossible to observe in practice due to redshift, as discussed in the following paragraph) is only larger than the number currently observable by a factor of 2.36.[19]

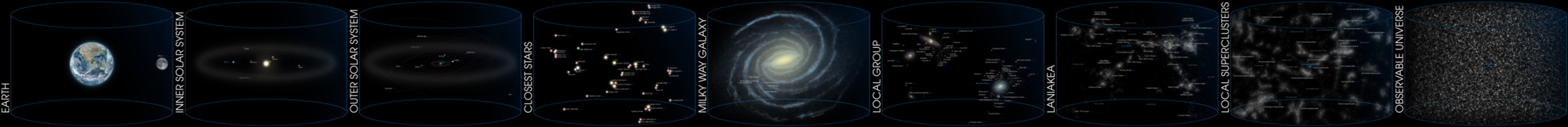

Artist's logarithmic scale conception of the observable universe with the Solar System at the center, inner and outer planets, Kuiper belt, Oort cloud, Alpha Centauri, Perseus Arm, Milky Way galaxy, Andromeda galaxy, nearby galaxies, Cosmic Web, Cosmic microwave radiation and the Big Bang's invisible plasma on the edge.

Though in principle more galaxies will become observable in the future, in practice an increasing number of galaxies will become extremely redshifted due to ongoing expansion, so much so that they will seem to disappear from view and become invisible.[20][21][22] An additional subtlety is that a galaxy at a given comoving distance is defined to lie within the "observable universe" if we can receive signals emitted by the galaxy at any age in its past history (say, a signal sent from the galaxy only 500 million years after the Big Bang), but because of the universe's expansion, there may be some later age at which a signal sent from the same galaxy can never reach the Earth at any point in the infinite future (so, for example, we might never see what the galaxy looked like 10 billion years after the Big Bang),[23] even though it remains at the same comoving distance (comoving distance is defined to be constant with time—unlike proper distance, which is used to define recession velocity due to the expansion of space), which is less than the comoving radius of the observable universe.[clarification needed] This fact can be used to define a type of cosmic event horizon whose distance from the Earth changes over time. For example, the current distance to this horizon is about 16 billion light-years, meaning that a signal from an event happening at present can eventually reach the Earth in the future if the event is less than 16 billion light-years away, but the signal will never reach the Earth if the event is more than 16 billion light-years away.[12]

Both popular and professional research articles in cosmology often use the term "universe" to mean "observable universe".[citation needed] This can be justified on the grounds that we can never know anything by direct experimentation about any part of the universe that is causally disconnected from the Earth, although many credible theories require a total universe much larger than the observable universe.[citation needed] No evidence exists to suggest that the boundary of the observable universe constitutes a boundary on the universe as a whole, nor do any of the mainstream cosmological models propose that the universe has any physical boundary in the first place, though some models propose it could be finite but unbounded, like a higher-dimensional analogue of the 2D surface of a sphere that is finite in area but has no edge. It is plausible that the galaxies within our observable universe represent only a minuscule fraction of the galaxies in the universe. According to the theory of cosmic inflation initially introduced by its founder, Alan Guth (and by D. Kazanas[24]), if it is assumed that inflation began about 10−37 seconds after the Big Bang, then with the plausible assumption that the size of the universe before the inflation occurred was approximately equal to the speed of light times its age, that would suggest that at present the entire universe's size is at least 3×1023 times the radius of the observable universe.[25] There are also lower estimates claiming that the entire universe is in excess of 250 times larger than the observable universe[26] and also higher estimates implying that the universe is at least 101010122 times larger than the observable universe.[27]

If the universe is finite but unbounded, it is also possible that the universe is smaller than the observable universe. In this case, what we take to be very distant galaxies may actually be duplicate images of nearby galaxies, formed by light that has circumnavigated the universe. It is difficult to test this hypothesis experimentally because different images of a galaxy would show different eras in its history, and consequently might appear quite different. Bielewicz et al.[28] claims to establish a lower bound of 27.9 gigaparsecs (91 billion light-years) on the diameter of the last scattering surface (since this is only a lower bound, the paper leaves open the possibility that the whole universe is much larger, even infinite). This value is based on matching-circle analysis of the WMAP 7 year data. This approach has been disputed.[29]

Size

Hubble Ultra-Deep Field image of a region of the observable universe (equivalent sky area size shown in bottom left corner), near the constellation Fornax. Each spot is a galaxy, consisting of billions of stars. The light from the smallest, most redshifted galaxies originated nearly 14 billion years ago.

The comoving distance from Earth to the edge of the observable universe is about 14.26 gigaparsecs (46.5 billion light-years or 4.40×1026 meters) in any direction. The observable universe is thus a sphere with a diameter of about 28.5 gigaparsecs[30] (93 billion light-years or 8.8×1026 meters).[31] Assuming that space is roughly flat (in the sense of being a Euclidean space), this size corresponds to a comoving volume of about 7004122000000000000♠1.22×104 Gpc3 (7005422000000000000♠4.22×105 Gly3 or 7080357000000000000♠3.57×1080 m3).[32]

The figures quoted above are distances now (in cosmological time), not distances at the time the light was emitted. For example, the cosmic microwave background radiation that we see right now was emitted at the time of photon decoupling, estimated to have occurred about 7005380000000000000♠380,000 years after the Big Bang,[33][34] which occurred around 13.8 billion years ago. This radiation was emitted by matter that has, in the intervening time, mostly condensed into galaxies, and those galaxies are now calculated to be about 46 billion light-years from us.[10][12] To estimate the distance to that matter at the time the light was emitted, we may first note that according to the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric, which is used to model the expanding universe, if at the present time we receive light with a redshift of z, then the scale factor at the time the light was originally emitted is given by[35][36]

a(t)=11+z{displaystyle !a(t)={frac {1}{1+z}}}

.

WMAP nine-year results combined with other measurements give the redshift of photon decoupling as z = 7003109164000000000♠1091.64±0.47,[37] which implies that the scale factor at the time of photon decoupling would be 1⁄1092.64. So if the matter that originally emitted the oldest CMBR photons has a present distance of 46 billion light-years, then at the time of decoupling when the photons were originally emitted, the distance would have been only about 42 million light-years.

Misconceptions on its size

An example of the misconception that the radius of the observable universe is 13 billion light-years. This plaque appears at the Rose Center for Earth and Space in New York City.

Many secondary sources have reported a wide variety of incorrect figures for the size of the visible universe. Some of these figures are listed below, with brief descriptions of possible reasons for misconceptions about them.

- 13.8 billion light-years

- The age of the universe is estimated to be 13.8 billion years. While it is commonly understood that nothing can accelerate to velocities equal to or greater than that of light, it is a common misconception that the radius of the observable universe must therefore amount to only 13.8 billion light-years. This reasoning would only make sense if the flat, static Minkowski spacetime conception under special relativity were correct. In the real universe, spacetime is curved in a way that corresponds to the expansion of space, as evidenced by Hubble's law. Distances obtained as the speed of light multiplied by a cosmological time interval have no direct physical significance.[38]

- 15.8 billion light-years

- This is obtained in the same way as the 13.8-billion-light-year figure, but starting from an incorrect age of the universe that the popular press reported in mid-2006.[39][40] For an analysis of this claim and the paper that prompted it, see the following reference at the end of this article.[41]

- 27.6 billion light-years

- This is a diameter obtained from the (incorrect) radius of 13.8 billion light-years.

- 78 billion light-years

- In 2003, Cornish et al.[42] found this lower bound for the diameter of the whole universe (not just the observable part), postulating that the universe is finite in size due to its having a nontrivial topology,[43][44] with this lower bound based on the estimated current distance between points that we can see on opposite sides of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR). If the whole universe is smaller than this sphere, then light has had time to circumnavigate it since the Big Bang, producing multiple images of distant points in the CMBR, which would show up as patterns of repeating circles.[45] Cornish et al. looked for such an effect at scales of up to 24 gigaparsecs (78 Gly or 7.4×1026 m) and failed to find it, and suggested that if they could extend their search to all possible orientations, they would then "be able to exclude the possibility that we live in a universe smaller than 24 Gpc in diameter". The authors also estimated that with "lower noise and higher resolution CMB maps (from WMAP's extended mission and from Planck), we will be able to search for smaller circles and extend the limit to ~28 Gpc."[42] This estimate of the maximum lower bound that can be established by future observations corresponds to a radius of 14 gigaparsecs, or around 46 billion light-years, about the same as the figure for the radius of the visible universe (whose radius is defined by the CMBR sphere) given in the opening section. A 2012 preprint by most of the same authors as the Cornish et al. paper has extended the current lower bound to a diameter of 98.5% the diameter of the CMBR sphere, or about 26 Gpc.[46]

- 156 billion light-years

- This figure was obtained by doubling 78 billion light-years on the assumption that it is a radius.[47] Because 78 billion light-years is already a diameter (the original paper by Cornish et al. says, "By extending the search to all possible orientations, we will be able to exclude the possibility that we live in a universe smaller than 24 Gpc in diameter," and 24 Gpc is 78 billion light-years),[42] the doubled figure is incorrect. This figure was very widely reported.[47][48][49] A press release from Montana State University–Bozeman, where Cornish works as an astrophysicist, noted the error when discussing a story that had appeared in Discover magazine, saying "Discover mistakenly reported that the universe was 156 billion light-years wide, thinking that 78 billion was the radius of the universe instead of its diameter."[50] As noted above, 78 billion was also incorrect.

- 180 billion light-years

- This estimate combines the erroneous 156-billion-light-year figure with evidence that the M33 Galaxy is actually fifteen percent farther away than previous estimates and that, therefore, the Hubble constant is fifteen percent smaller.[51] The 180-billion figure is obtained by adding 15% to 156 billion light-years.

Large-scale structure

Galaxy clusters, like RXC J0142.9+4438, are the nodes of the cosmic web that permeates the entire Universe.[52]

Sky surveys and mappings of the various wavelength bands of electromagnetic radiation (in particular 21-cm emission) have yielded much information on the content and character of the universe's structure. The organization of structure appears to follow as a hierarchical model with organization up to the scale of superclusters and filaments. Larger than this (at scales between 30 and 200 megaparsecs[53]), there seems to be no continued structure, a phenomenon that has been referred to as the End of Greatness.[54]

Walls, filaments, nodes, and voids

DTFE reconstruction of the inner parts of the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey

The organization of structure arguably begins at the stellar level, though most cosmologists rarely address astrophysics on that scale. Stars are organized into galaxies, which in turn form galaxy groups, galaxy clusters, superclusters, sheets, walls and filaments, which are separated by immense voids, creating a vast foam-like structure[55] sometimes called the "cosmic web". Prior to 1989, it was commonly assumed that virialized galaxy clusters were the largest structures in existence, and that they were distributed more or less uniformly throughout the universe in every direction. However, since the early 1980s, more and more structures have been discovered. In 1983, Adrian Webster identified the Webster LQG, a large quasar group consisting of 5 quasars. The discovery was the first identification of a large-scale structure, and has expanded the information about the known grouping of matter in the universe. In 1987, Robert Brent Tully identified the Pisces–Cetus Supercluster Complex, the galaxy filament in which the Milky Way resides. It is about 1 billion light-years across. That same year, an unusually large region with a much lower than average distribution of galaxies was discovered, the Giant Void, which measures 1.3 billion light-years across. Based on redshift survey data, in 1989 Margaret Geller and John Huchra discovered the "Great Wall",[56] a sheet of galaxies more than 500 million light-years long and 200 million light-years wide, but only 15 million light-years thick. The existence of this structure escaped notice for so long because it requires locating the position of galaxies in three dimensions, which involves combining location information about the galaxies with distance information from redshifts.

Two years later, astronomers Roger G. Clowes and Luis E. Campusano discovered the Clowes–Campusano LQG, a large quasar group measuring two billion light-years at its widest point which was the largest known structure in the universe at the time of its announcement. In April 2003, another large-scale structure was discovered, the Sloan Great Wall. In August 2007, a possible supervoid was detected in the constellation Eridanus.[57] It coincides with the 'CMB cold spot', a cold region in the microwave sky that is highly improbable under the currently favored cosmological model. This supervoid could cause the cold spot, but to do so it would have to be improbably big, possibly a billion light-years across, almost as big as the Giant Void mentioned above.

Computer simulated image of an area of space more than 50 million light-years across, presenting a possible large-scale distribution of light sources in the universe—precise relative contributions of galaxies and quasars are unclear.

Another large-scale structure is the SSA22 Protocluster, a collection of galaxies and enormous gas bubbles that measures about 200 million light-years across.

In 2011, a large quasar group was discovered, U1.11, measuring about 2.5 billion light-years across. On January 11, 2013, another large quasar group, the Huge-LQG, was discovered, which was measured to be four billion light-years across, the largest known structure in the universe at that time.[58] In November 2013, astronomers discovered the Hercules–Corona Borealis Great Wall,[59][60] an even bigger structure twice as large as the former. It was defined by the mapping of gamma-ray bursts.[59][61]

End of Greatness

The End of Greatness is an observational scale discovered at roughly 100 Mpc (roughly 300 million light-years) where the lumpiness seen in the large-scale structure of the universe is homogenized and isotropized in accordance with the Cosmological Principle.[54] At this scale, no pseudo-random fractalness is apparent.[62]

The superclusters and filaments seen in smaller surveys are randomized to the extent that the smooth distribution of the universe is visually apparent. It was not until the redshift surveys of the 1990s were completed that this scale could accurately be observed.[54]

Observations

"Panoramic view of the entire near-infrared sky reveals the distribution of galaxies beyond the Milky Way. The image is derived from the 2MASS Extended Source Catalog (XSC)—more than 1.5 million galaxies, and the Point Source Catalog (PSC)—nearly 0.5 billion Milky Way stars. The galaxies are color-coded by 'redshift' obtained from the UGC, CfA, Tully NBGC, LCRS, 2dF, 6dFGS, and SDSS surveys (and from various observations compiled by the NASA Extragalactic Database), or photo-metrically deduced from the K band (2.2 μm). Blue are the nearest sources (z < 0.01); green are at moderate distances (0.01 < z < 0.04) and red are the most distant sources that 2MASS resolves (0.04 < z < 0.1). The map is projected with an equal area Aitoff in the Galactic system (Milky Way at center)."[63]

Another indicator of large-scale structure is the 'Lyman-alpha forest'. This is a collection of absorption lines that appear in the spectra of light from quasars, which are interpreted as indicating the existence of huge thin sheets of intergalactic (mostly hydrogen) gas. These sheets appear to be associated with the formation of new galaxies.

Caution is required in describing structures on a cosmic scale because things are often different from how they appear. Gravitational lensing (bending of light by gravitation) can make an image appear to originate in a different direction from its real source. This is caused when foreground objects (such as galaxies) curve surrounding spacetime (as predicted by general relativity), and deflect passing light rays. Rather usefully, strong gravitational lensing can sometimes magnify distant galaxies, making them easier to detect. Weak lensing (gravitational shear) by the intervening universe in general also subtly changes the observed large-scale structure.

The large-scale structure of the universe also looks different if one only uses redshift to measure distances to galaxies. For example, galaxies behind a galaxy cluster are attracted to it, and so fall towards it, and so are slightly blueshifted (compared to how they would be if there were no cluster) On the near side, things are slightly redshifted. Thus, the environment of the cluster looks a bit squashed if using redshifts to measure distance. An opposite effect works on the galaxies already within a cluster: the galaxies have some random motion around the cluster center, and when these random motions are converted to redshifts, the cluster appears elongated. This creates a "finger of God"—the illusion of a long chain of galaxies pointed at the Earth.

Cosmography of Earth's cosmic neighborhood

At the centre of the Hydra-Centaurus Supercluster, a gravitational anomaly called the Great Attractor affects the motion of galaxies over a region hundreds of millions of light-years across. These galaxies are all redshifted, in accordance with Hubble's law. This indicates that they are receding from us and from each other, but the variations in their redshift are sufficient to reveal the existence of a concentration of mass equivalent to tens of thousands of galaxies.

The Great Attractor, discovered in 1986, lies at a distance of between 150 million and 250 million light-years (250 million is the most recent estimate), in the direction of the Hydra and Centaurus constellations. In its vicinity there is a preponderance of large old galaxies, many of which are colliding with their neighbours, or radiating large amounts of radio waves.

In 1987, astronomer R. Brent Tully of the University of Hawaii's Institute of Astronomy identified what he called the Pisces–Cetus Supercluster Complex, a structure one billion light-years long and 150 million light-years across in which, he claimed, the Local Supercluster was embedded.[64][65]

Mass of ordinary matter

The mass of the observable universe is often quoted as 1050 tonnes or 1053 kg.[66] In this context, mass refers to ordinary matter and includes the interstellar medium (ISM) and the intergalactic medium (IGM). However, it excludes dark matter and dark energy. This quoted value for the mass of ordinary matter in the universe can be estimated based on critical density. The calculations are for the observable universe only as the volume of the whole is unknown and may be infinite.

Estimates based on critical density

Critical density is the energy density for which the universe is flat.[67] If there is no dark energy, it is also the density for which the expansion of the universe is poised between continued expansion and collapse.[68] From the Friedmann equations, the value for ρc{displaystyle rho _{c}}

- ρc=3H28πG,{displaystyle rho _{c}={frac {3H^{2}}{8pi G}},}

where G is the gravitational constant and H = H0 is the present value of the Hubble constant. The current value for H0, due to the European Space Agency's Planck Telescope, is H0 = 67.15 kilometers per second per mega parsec. This gives a critical density of 6973850000000000000♠0.85×10−26 kg/m3 (commonly quoted as about 5 hydrogen atoms per cubic meter). This density includes four significant types of energy/mass: ordinary matter (4.8%), neutrinos (0.1%), cold dark matter (26.8%), and dark energy (68.3%).[70] Note that although neutrinos are Standard Model particles, they are listed separately because they are difficult to detect and so different from ordinary matter. The density of ordinary matter, as measured by Planck, is 4.8% of the total critical density or 6972408000000000000♠4.08×10−28 kg/m3. To convert this density to mass we must multiply by volume, a value based on the radius of the "observable universe". Since the universe has been expanding for 13.8 billion years, the comoving distance (radius) is now about 46.6 billion light-years. Thus, volume (4/3πr3) equals 7080358000000000000♠3.58×1080 m3 and the mass of ordinary matter equals density (6972408000000000000♠4.08×10−28 kg/m3) times volume (7080358000000000000♠3.58×1080 m3) or 7053146000000000000♠1.46×1053 kg.

Matter content – number of atoms

Assuming the mass of ordinary matter is about 7053144999999999999♠1.45×1053 kg (refer to previous section) and assuming all atoms are hydrogen atoms (which are about 74% of all atoms in our galaxy by mass, see Abundance of the chemical elements), calculating the estimated total number of atoms in the observable universe is straightforward. Divide the mass of ordinary matter by the mass of a hydrogen atom (7053144999999999999♠1.45×1053 kg divided by 6973167000000000000♠1.67×10−27 kg). The result is approximately 1080 hydrogen atoms.

Most distant objects

The most distant astronomical object yet announced as of 2016 is a galaxy classified GN-z11. In 2009, a gamma ray burst, GRB 090423, was found to have a redshift of 8.2, which indicates that the collapsing star that caused it exploded when the universe was only 630 million years old.[71] The burst happened approximately 13 billion years ago,[72] so a distance of about 13 billion light-years was widely quoted in the media (or sometimes a more precise figure of 13.035 billion light-years),[71] though this would be the "light travel distance" (see Distance measures (cosmology)) rather than the "proper distance" used in both Hubble's law and in defining the size of the observable universe (cosmologist Ned Wright argues against the common use of light travel distance in astronomical press releases on this page, and at the bottom of the page offers online calculators that can be used to calculate the current proper distance to a distant object in a flat universe based on either the redshift z or the light travel time). The proper distance for a redshift of 8.2 would be about 9.2 Gpc,[73] or about 30 billion light-years. Another record-holder for most distant object is a galaxy observed through and located beyond Abell 2218, also with a light travel distance of approximately 13 billion light-years from Earth, with observations from the Hubble telescope indicating a redshift between 6.6 and 7.1, and observations from Keck telescopes indicating a redshift towards the upper end of this range, around 7.[74] The galaxy's light now observable on Earth would have begun to emanate from its source about 750 million years after the Big Bang.[75]

Horizons

The limit of observability in our universe is set by a set of cosmological horizons which limit—based on various physical constraints—the extent to which we can obtain information about various events in the universe. The most famous horizon is the particle horizon which sets a limit on the precise distance that can be seen due to the finite age of the universe. Additional horizons are associated with the possible future extent of observations (larger than the particle horizon owing to the expansion of space), an "optical horizon" at the surface of last scattering, and associated horizons with the surface of last scattering for neutrinos and gravitational waves.

See also

- Bolshoi Cosmological Simulation

Causality (physics) – The relationship between causes and effects

Chronology of the universe – The history and future of the universe according to Big Bang cosmology

Dark flow – A possible non-random component of the peculiar velocity of galaxy clusters- Hubble volume

- Illustris project

- Multiverse

Orders of magnitude (length) – Range of lengths from the subatomic to the astronomical scales

References

^ Itzhak Bars; John Terning (November 2009). Extra Dimensions in Space and Time. Springer. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-387-77637-8. Retrieved 2011-05-01..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ What is the Universe Made Of?

^ Multiply percentage of ordinary matter given by Planck below, with total energy density given by WMAP below

^ http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_matter.html January 13, 2015

^ ab Planck Collaboration (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters (See Table 4 on page 31 of pfd)". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594: A13. arXiv:1502.01589. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A..13P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525830.

^ Fixsen, D. J. (December 2009). "The Temperature of the Cosmic Microwave Background". The Astrophysical Journal. 707 (2): 916–920. arXiv:0911.1955. Bibcode:2009ApJ...707..916F. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/707/2/916.

^ "Planck cosmic recipe".

^ Conselice, Christopher J.; et al. (2016). "The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and Its Implications". The Astrophysical Journal. 830 (2): 83. arXiv:1607.03909v2. Bibcode:2016ApJ...830...83C. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/830/2/83.

^ Fountain, Henry (17 October 2016). "Two Trillion Galaxies, at the Very Least". New York Times. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

^ ab Gott III, J. Richard; Mario Jurić; David Schlegel; Fiona Hoyle; et al. (2005). "A Map of the Universe" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 624 (2): 463–484. arXiv:astro-ph/0310571. Bibcode:2005ApJ...624..463G. doi:10.1086/428890.

^ Frequently Asked Questions in Cosmology. Astro.ucla.edu. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ abcd Lineweaver, Charles; Tamara M. Davis (2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American. 292 (3): 36–45. Bibcode:2005SciAm.292c..36L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0305-36.

^ Itzhak Bars; John Terning (November 2009). Extra Dimensions in Space and Time. Springer. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-387-77637-8. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ See the "Mass of ordinary matter" section in this article.

^ Overbye, Dennis (3 December 2018). "All the Light There Is to See? 4 x 10⁸⁴ Photons". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

^ The Fermi-LAT Collaboration (30 November 2018). "A gamma-ray determination of the Universe's star formation history". Science. 362 (6418): 1031–1034. arXiv:1812.01031. Bibcode:2018Sci...362.1031F. doi:10.1126/science.aat8123. PMID 30498122.

^ Loeb, Abraham (2002). "Long-term future of extragalactic astronomy". Physical Review D. 65 (4): 047301. arXiv:astro-ph/0107568. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65d7301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.047301.

^ Is the universe expanding faster than the speed of light? (see the last two paragraphs)

^ The comoving distance of the future visibility limit is calculated on p. 8 of Gott et al.'s A Map of the Universe to be 4.50 times the Hubble radius, given as 4.220 billion parsecs (13.76 billion light-years), whereas the current comoving radius of the observable universe is calculated on p. 7 to be 3.38 times the Hubble radius. The number of galaxies in a sphere of a given comoving radius is proportional to the cube of the radius, so as shown on p. 8 the ratio between the number of galaxies observable in the future visibility limit to the number of galaxies observable today would be (4.50/3.38)3 = 2.36.

^ Krauss, Lawrence M.; Robert J. Scherrer (2007). "The Return of a Static Universe and the End of Cosmology". General Relativity and Gravitation. 39 (10): 1545–1550. arXiv:0704.0221. Bibcode:2007GReGr..39.1545K. doi:10.1007/s10714-007-0472-9.

^ Using Tiny Particles To Answer Giant Questions. Science Friday, 3 Apr 2009. According to the transcript, Brian Greene makes the comment "And actually, in the far future, everything we now see, except for our local galaxy and a region of galaxies will have disappeared. The entire universe will disappear before our very eyes, and it's one of my arguments for actually funding cosmology. We've got to do it while we have a chance."

^ See also Faster than light#Universal expansion and Future of an expanding universe#Galaxies outside the Local Supercluster are no longer detectable.

^ Loeb, Abraham (2002). "The Long-Term Future of Extragalactic Astronomy". Physical Review D. 65 (4). arXiv:astro-ph/0107568. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65d7301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.047301.

^ "Dynamics of the Universe and Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking" Kazanas, D., Ap. J. (Lett.), 241, L59-L63.

^ Alan H. Guth (17 March 1998). The inflationary universe: the quest for a new theory of cosmic origins. Basic Books. pp. 186–. ISBN 978-0-201-32840-0. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ Universe Could be 250 Times Bigger Than What is Observable – by Vanessa D'Amico on February 8, 2011 http://www.universetoday.com/83167/universe-could-be-250-times-bigger-than-what-is-observable/

^ Page, Don N. (2007). "Susskind's Challenge to the Hartle–Hawking No-Boundary Proposal and Possible Resolutions". Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics. 2007 (1): 004. arXiv:hep-th/0610199. Bibcode:2007JCAP...01..004P. doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2007/01/004.

^ Bielewicz, P.; Banday, A. J.; Gorski, K. M. (2013). Auge, E.; Dumarchez, J.; Tran Thanh Van, J., eds. "Constraints on the Topology of the Universe". Proceedings of the XLVIIth Rencontres de Moriond. 2012 (91). arXiv:1303.4004. Bibcode:2013arXiv1303.4004B.

^ Mota; Reboucas; Tavakol (2010). "Observable circles-in-the-sky in flat universes". arXiv:1007.3466 [astro-ph.CO].

^ "WolframAlpha". Retrieved 29 November 2011.

^ "WolframAlpha". Retrieved 29 November 2011.

^ "WolframAlpha". Retrieved 15 February 2016.

^ "Seven-Year Wilson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Sky Maps, Systematic Errors, and Basic Results" (PDF). nasa.gov. Retrieved 2010-12-02. (see p. 39 for a table of best estimates for various cosmological parameters)

^ Abbott, Brian (May 30, 2007). "Microwave (WMAP) All-Sky Survey". Hayden Planetarium. Retrieved 2008-01-13.

^ Paul Davies (28 August 1992). The new physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 187–. ISBN 978-0-521-43831-5. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ V. F. Mukhanov (2005). Physical foundations of cosmology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-0-521-56398-7. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ Bennett, C. L.; Larson, D.; Weiland, J. L.; Jarosik, N.; et al. (1 October 2013). "Nine-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Final Maps and Results". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 208 (2): 20. arXiv:1212.5225. Bibcode:2013ApJS..208...20B. doi:10.1088/0067-0049/208/2/20.

^ Ned Wright, "Why the Light Travel Time Distance should not be used in Press Releases".

^ Universe Might be Bigger and Older than Expected. Space.com (2006-08-07). Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ Big bang pushed back two billion years – space – 04 August 2006 – New Scientist. Space.newscientist.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ Edward L. Wright, "An Older but Larger Universe?"

^ abc Cornish; Spergel; Starkman; Eiichiro Komatsu (May 2004) [October 2003 (arXiv)]. "Constraining the Topology of the Universe". Phys. Rev. Lett. 92 (20): 201302. arXiv:astro-ph/0310233. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92t1302C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.201302. PMID 15169334. 201302.

^ Levin, Janna (January 2000). "In space, do all roads lead to home?". plus.maths.org. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-29. Retrieved 2011-09-18.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ Bob Gardner's "Topology, Cosmology and Shape of Space" Talk, Section 7 Archived 2012-08-02 at Archive.today. Etsu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ Vaudrevange; Starkmanl; Cornish; Spergel (2012). "Constraints on the Topology of the Universe: Extension to General Geometries". Physical Review D. 86 (8): 083526. arXiv:1206.2939. Bibcode:2012PhRvD..86h3526V. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.86.083526.

^ ab SPACE.com – Universe Measured: We're 156 Billion Light-years Wide!

^ Roy, Robert. (2004-05-24) New study super-sizes the universe – Technology & science – Space – Space.com – msnbc.com. MSNBC. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ "Astronomers size up the Universe". BBC News. 2004-05-28. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

^ "MSU researcher recognized for discoveries about universe". 2004-12-21. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

^ Space.com – Universe Might be Bigger and Older than Expected

^ "Galactic treasure chest". www.spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2013-07-23). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (International ed.). Pearson. p. 1178. ISBN 9781292022932.

^ abc Robert P Kirshner (2002). The Extravagant Universe: Exploding Stars, Dark Energy and the Accelerating Cosmos. Princeton University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-691-05862-7.

^ Carroll, Bradley W.; Ostlie, Dale A. (2013-07-23). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (International ed.). Pearson. pp. 1173–1174. ISBN 9781292022932.

^ M. J. Geller; J. P. Huchra (1989). "Mapping the universe". Science. 246 (4932): 897–903. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..897G. doi:10.1126/science.246.4932.897. PMID 17812575.

^ Biggest void in space is 1 billion light years across – space – 24 August 2007 – New Scientist. Space.newscientist.com. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ Wall, Mike (2013-01-11). "Largest structure in universe discovered". Fox News.

^ ab Horváth, I; Hakkila, Jon; Bagoly, Z. (2014). "Possible structure in the GRB sky distribution at redshift two". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 561: L12. arXiv:1401.0533. Bibcode:2014A&A...561L..12H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201323020.

^ Horvath, I.; Hakkila, J.; Bagoly, Z. (2013). "The largest structure of the Universe, defined by Gamma-Ray Bursts". arXiv:1311.1104 [astro-ph.CO].

^ Klotz, Irene (2013-11-19). "Universe's Largest Structure is a Cosmic Conundrum". Discovery.

^ LiveScience.com, "The Universe Isn't a Fractal, Study Finds", Natalie Wolchover,22 August 2012

^ 1Jarrett, T. H. (2004). "Large Scale Structure in the Local Universe: The 2MASS Galaxy Catalog". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia. 21 (4): 396–403. arXiv:astro-ph/0405069. Bibcode:2004PASA...21..396J. doi:10.1071/AS04050.

^ Massive Clusters of Galaxies Defy Concepts of the Universe N.Y. Times Tue. November 10, 1987:

^ Map of the Pisces-Cetus Supercluster Complex:

^ Paul Davies (2006). The Goldilocks Enigma. First Mariner Books. p. 43–. ISBN 978-0-618-59226-5.

^ See Friedmann equations#Density parameter.

^ Michio Kaku (2005). Parallel Worlds. Anchor Books. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-4000-3372-0. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

^ Bernard F. Schutz (2003). Gravity from the ground up. Cambridge University Press. pp. 361–. ISBN 978-0-521-45506-0. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

^ Planck collaboration (2013). "Planck 2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 571: A16. arXiv:1303.5076. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A..16P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591.

^ ab New Gamma-Ray Burst Smashes Cosmic Distance Record – NASA Science. Science.nasa.gov. Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ More Observations of GRB 090423, the Most Distant Known Object in the Universe. Universetoday.com (2009-10-28). Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ Meszaros, Attila; et al. (2009). "Impact on cosmology of the celestial anisotropy of the short gamma-ray bursts". Baltic Astronomy. 18: 293–296. arXiv:1005.1558. Bibcode:2009BaltA..18..293M.

^ Hubble and Keck team up to find farthest known galaxy in the Universe|Press Releases|ESA/Hubble. Spacetelescope.org (2004-02-15). Retrieved on 2011-05-01.

^ MSNBC: "Galaxy ranks as most distant object in cosmos"

Further reading

Vicent J. Martínez; Jean-Luc Starck; Enn Saar; David L. Donoho; et al. (2005). "Morphology Of The Galaxy Distribution From Wavelet Denoising". The Astrophysical Journal. 634 (2): 744–755. arXiv:astro-ph/0508326. Bibcode:2005ApJ...634..744M. doi:10.1086/497125.

Mureika, J. R. & Dyer, C. C. (2004). "Review: Multifractal Analysis of Packed Swiss Cheese Cosmologies". General Relativity and Gravitation. 36 (1): 151–184. arXiv:gr-qc/0505083. Bibcode:2004GReGr..36..151M. doi:10.1023/B:GERG.0000006699.45969.49.

Gott, III, J. R.; et al. (May 2005). "A Map of the Universe". The Astrophysical Journal. 624 (2): 463–484. arXiv:astro-ph/0310571. Bibcode:2005ApJ...624..463G. doi:10.1086/428890.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

F. Sylos Labini; M. Montuori & L. Pietronero (1998). "Scale-invariance of galaxy clustering". Physics Reports. 293 (1): 61–226. arXiv:astro-ph/9711073. Bibcode:1998PhR...293...61S. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(97)00044-6.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Calculating the total mass of ordinary matter in the universe, what you always wanted to know

"Millennium Simulation" of structure forming – Max Planck Institute of Astrophysics, Garching, Germany

Visualisations of large-scale structure: animated spins of groups, clusters, filaments and voids – identified in SDSS data by MSPM (Sydney Institute for Astronomy)- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: The Sloan Great Wall: Largest Known Structure? (7 November 2007)

- Cosmology FAQ

- Forming Galaxies Captured In The Young Universe By Hubble, VLT & Spitzer

- NASA featured Images and Galleries

- Star Survey reaches 70 sextillion

- Animation of the cosmic light horizon

- Inflation and the Cosmic Microwave Background by Charles Lineweaver

- Logarithmic Maps of the Universe

- List of publications of the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey

The Universe Within 14 Billion Light Years – NASA Atlas of the Universe – Note, this map only gives a rough cosmographical estimate of the expected distribution of superclusters within the observable universe; very little actual mapping has been done beyond a distance of one billion light-years.- Video: The Known Universe, from the American Museum of Natural History

- NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database

Cosmography of the Local Universe at irfu.cea.fr (17:35) (arXiv)

Size and age of the Universe – at Astronoo