Scandinavian folklore

Scandinavian folklore or Nordic folklore is the folklore of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland and the Faroe Islands. It has common roots as, and have been mutually influenced by, folklore in England, Germany, the Baltic countries, Finland and Sapmi. Folklore is a concept encompassing expressive traditions of a particular culture or group. The peoples of Scandinavia are heterogenous, as are the oral genres and material culture that has been common in their lands. However, there are some commonalities across Scandinavian folkloric traditions, among them a common ground in elements from Norse mythology as well as Christian conceptions of the world.

Among the many tales common in Scandinavian oral traditions, some have become known beyond Scandinavian borders - examples include The Three Billy Goats Gruff and The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body.

Contents

1 Beings

1.1 Trolls

1.2 Huldra

1.3 Nattmara/nightmare

1.4 Nøkken

1.5 Others

2 See also

3 References

4 External links

Beings

A large number of different mythological creatures from Scandinavian folklore have become well-known in other parts of the world, mainly through popular culture and fantasy genres. Some of these are:

Trolls

Mother Troll and Her Sons by Swedish painter John Bauer, 1915.

Troll (Norwegian), trolde (Danish) is a designation for several types of human-like supernatural beings in Scandinavian folklore. They are mentioned in the Edda (1220) as a monster with many heads. Later, trolls became characters in fairy tales, legends and ballads. They play a main part in many of the fairy tales from Asbjørnsen and Moes collections of Norwegian tales (1844). Trolls may be compared to many supernatural beings in other cultures, for instance the cyclops of Greek legends. In Swedish, such beings are often termed 'jætte' (giant), a word related to the Norse 'jotun'. The origins of the word troll is uncertain.

Trolls are described in many ways in Scandinavian folk litterature, but they are often portrayed as stupid, and slow to act. In fairy tales and legends about trolls, the plot is often that a human with courage and presence of mind can outwit a troll. Sometimes saints' legends involve a holy man tricking an enormous troll to build a church. Trolls come in many different shapes and forms, and are generally not fair to behold, as they can have as many as nine heads. Trolls live throughout the land, dwelling in mountains, under bridges, and at the bottom of lakes. Trolls who live in the mountains may be very wealthy, hoarding mounds of gold and silver in their cliff dwellings. Dovregubben, a troll king, lives inside the Dovre Mountains with his court, described in detail in Ibsen's Peer Gynt. Trolls hate church-bells and the smell of Christians.

Huldra

The Huldra, Hylda, Skogsrå or Skogfru (Forest wife/woman) is a dangerous seductress who lives in the forest. The Huldra is said to lure men with her charm. She has a long cow's tail that she ties under her skirt in order to hide it from men. If she can manage to get married in a church, her tail falls off and she becomes human.

Nattmara/nightmare

In Scandinavia, there existed the famous race of she-werewolves known with a name of Nattmara. The mara (or nightmare, as is the English word for them) appears as a skinny young woman, dressed in a nightgown, with pale skin and long black hair and nails. As sand they could slip through the slightest crack in the wood of a wall and terrorize the sleeping by "riding" on their chest, thus giving them nightmares. They would sometimes ride cattle that, when touched by the Mara, would have their hair or fur tangled and energy drained, while trees would curl up and wilt. In some tales they had a similar role to the Banshee as an omen of death and if one were to leave a dirty doll in a family living room, one of the members would soon fall ill and die of tuberculosis (also called "lung soot", referring to how the lack of proper chimneys in old 18–19th century homes led to many contracting aforementioned diseases due to inhaling smoke on a daily basis).

There is controversy as to how they came into being and in some tales, the Maras are simply restless children, whose souls leave their body at night to haunt the living. If a woman were to have a horse placenta pulled over her head before giving birth, the children would be delivered safely; but all the boys will turn into werewolves, and all the girls will become Maras.

Nøkken

Theodor Kittelsen's Nøkken from 1904

Nøkken, näcken, or strömkarlen, is a dangerous fresh water dwelling. The nøkk plays a violin to lure his victims out onto thin ice or in leaky boats and then draws them down to the bottom of the water where he is waiting for them. The nøkk is also a known shapeshifter, usually changing into a horse or a man in order to lure his victims to him.

Others

An illustration made by Gudmund Stenersen of an angry nisse stealing hay from a farmer

The Nisse or tomte (in the southern Sweden and Norway and Denmark) is a good wight who takes care of the house and barn when the farmer is asleep, but only if the farmer reciprocates by setting out food for the nisse and he himself also takes care of his family, farm and animals. If the nisse is ignored or maltreated or the farm is not cared for, he can sabotage a lot of the work on the farm to teach the farmer a lesson or two. Although the nisse should be treated with respect and some degree of kindness, he should not be treated too kindly. In fact, there's a Swedish story in which a farmer and his wife enter their barn an early morning and find the little grey old man brushing the floor. They see his clothing, which is nothing more than torn rags, so the wife decides to make him some new clothes; but when the nisse finds them in the barn he now thinks he is too elegant to perform any more farm labour and thus disappears from the farm. Nisser are also usually associated with Christmas and the yule time. It is normal that farms may place bowls of rice porridge on the doorsteps in a similar manner that cookies and milk are put out for Santa Claus. In the morning the porridge would have been eaten. Some believe that the nisse brings the presents as well. In Swedish, the word Tomten (Tomte in singular) is very closely linked to the word for the plot of land where a house or cottage is built, which spells the same both in singular and plural (Tomten/tomterna) but is pronounced with slightly longer vocals. Therefore some scholars believe that the wight Tomten originates from some sort of general house god or deity from before the Asa belief. A Nisse/Tomte is said to be able to change his size between that of a 5-year-old child and a thumb, and also to have the ability to make himself invisible.

A type of wight from Northern Sweden called Vittra lives underground, is invisible most of the time and has its own cattle. Most of the time Vittra are rather distant and do not meddle in human affairs, but are fearsome when enraged. This can be achieved by not respecting them properly, for example by neglecting to perform certain rituals (such as saying "look out" when putting out hot water or going to the toilet so they can move out of the way) or building your home too close to or, even worse, on top of their home, disturbing their cattle or blocking their roads. They can make your life very very miserable or even dangerous – they do whatever it takes to drive you away, even arrange accidents that will harm or even kill you. Even in modern days, people have rebuilt or moved houses in order not to block a "Vittra-way", or moved from houses that are deemed a "Vittra-place" (Vittra ställe) because of bad luck – although this is rather uncommon. In tales told in the north of Sweden, Vittra often take the place that trolls, tomte and vättar hold in the same stories told in other parts of the country. Vittra are believed to sometimes "borrow" cattle that later would be returned to the owner with the ability to give more milk as a sign of gratitude. This tradition is heavily influenced by the fact that it was developed during a time when people let their cattle graze on mountains or in the forest for long periods of the year.

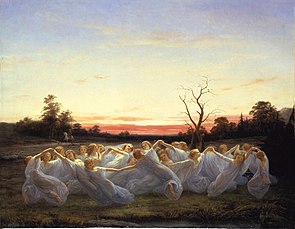

Ängsälvor, "meadow elves", (1850), painting by Nils Blommér

Elves (in Swedish, Älva if female and Alf if male, Alv in Norwegian, and Elver in Danish) are in some parts mostly described as female (in contrast to the light and dark elves in the Edda), otherworldly, beautiful and seductive residents of forests, meadows and mires. They are skilled in magic and illusions. Sometimes they are described as small fairies, sometimes as full-sized women and sometimes as half transparent spirits, or a mix thereof. They are closely linked to the mist and it is often said in Sweden that, "the Elves are dancing in the mist". The female form of Elves may have originated from the female deities called Dís (singular) and Díser (plural) found in pre-Christian Scandinavian religion. They were very powerful spirits closely linked to the seid magic. Even today the word "dis" is a synonym for mist or very light rain in Swedish, Norwegian and Danish. Particularly in Denmark, the female elves have merged with the dangerous and seductive huldra, skogsfrun or "keeper of the forest", often called hylde. In some parts of Sweden the elves also got some features from Skogsfrun, Huldra", or Hylda", and can seduce and bewitch careless men and suck the life out of them or make them go down in the mire and drown. But at the same time the Skogsrå exists as its own being, with other distinct features clearly separating it from the elves. In more modern tales, it isn't uncommon for a rather ugly male Tomte, Troll, Vätte or a Dwarf to fall in love with a beautiful Elven female, as the beginning of a story of impossible or forbidden love.

See also

Scandinavian folklore portal

Scandinavian folklore portal

- Danish folklore

Henrik Ibsen's 1867 play Peer Gynt

- Huldufólk

Norske Folkeeventyr, a collection of Norwegian folktales- Norse Mythology

- Thunderstone (folklore)

References

.mw-parser-output .refbegin{font-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul{list-style-type:none;margin-left:0}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>dd{margin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none}.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100{font-size:100%}

.mw-parser-output .smallcaps{font-variant:small-caps}

Reidar Th. Christiansen (1964). Folktales of Norway

Reimund Kvideland and Henning K. Sehmsdorf (1988). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend University of Minnesota. .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-8166-1503-9

Day, David (2003). The World of Tolkien: Mythological Sources of The Lord of the Rings

ISBN 0-517-22317-1

Wood, Edward J. (1868). Giants and Dwarfs. London: Folcroft Library.

Thompson, Stith (1961). "Folklore Trends in Scandinavia" in Dorson, Richard M. Folklore Research around the World. Indiana University Press.

Hopp, Zinken (1961). Norwegian Folklore Simplified. Trans. Toni Rambolt. Chester Springs, PA: Dufour Editions.

Craigie, William A. (1896). Scandinavian Folklore: Illustrations of the Traditional Beliefs of the Northern People. London: Alexander Garnder

Rose, Carol (1996). Spirits, Fairies, Leprechauns, and Goblins. New York: W.W. Norton & Company

ISBN 0-87436-811-1

Jones, Gwyn (1956). Scandinavian Legends and Folk-tales. New York: Oxford University

Oliver, Alberto (24 June 2009). The Tomte and Other Scandinavian Folklore Creatures. Community of Sweden. Visit Sweden. Web. 4 May 2010.

MacCulloch, J.A. (1948). The Celtic and Scandinavian Religions. Chicago: Academy Chicago

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Folklore of Scandinavia. |

- Norwegian folktales in English translation