Chiltern Hills

| Chiltern Hills | |

|---|---|

Near Nettlebed | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Haddington Hill |

| Elevation | 267 m (876 ft) |

| Dimensions | |

| Length | 74 km (46 mi) |

| Width | 18 km (11 mi) |

| Area | 833 km2 (322 sq mi) |

| Geography | |

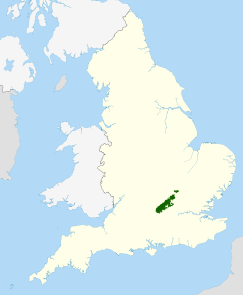

Location of the Chiltern Hills AONB in the UK | |

| Location | South East of England |

| Country | England |

| Counties | Bedfordshire Buckinghamshire Hertfordshire Oxfordshire |

| Range coordinates | 51°40′N 0°55′W / 51.667°N 0.917°W / 51.667; -0.917Coordinates: 51°40′N 0°55′W / 51.667°N 0.917°W / 51.667; -0.917 |

| Geology | |

| Type of rock | chalk downland |

The Chiltern Hills or, as they are known locally and historically, the Chilterns, is a range of hills northwest of London. They form a chalk escarpment across Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, and Bedfordshire.[1] A large portion of the hills was designated officially as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1965.

The Chilterns cover an area of 322 square miles (830 km2) stretching 45 miles (72 km) in a southwest to a northeast diagonal from Goring-on-Thames, Oxfordshire to Hitchin, Hertfordshire. At their widest, they are 12 miles (19 km).[2]

The northwest boundary of the hills is clearly defined by the escarpment. The dip slope is by definition more gradual, and merges with the landscape to the southeast.[3] The southwest endpoint is the River Thames. The hills decline slowly in prominence northeast of Luton, t[4]

Contents

1 Geology

2 Physical characteristics

2.1 Topography

2.2 Landscape and land use

2.3 Rivers

2.4 Transport routes

3 History

4 Settlement

4.1 List of towns and villages in the Chiltern hills area

4.2 Strip parishes associated with the Chilterns

5 Economic use

6 Protection

6.1 Chilterns Conservation Board

6.2 High Speed Rail 2

7 Chiltern Hundreds

8 See also

9 References

10 External links

Geology

Chalk soil at the foot of the escarpment of the Chiltern Hills near Shirburn Hill

Stokenchurch Gap, a cutting built to carry the M40 motorway through a section of the Chilterns.

The chalk escarpment of the Chiltern Hills overlooks the Vale of Aylesbury, and roughly coincides with the southernmost extent of the ice sheet during the Anglian glacial maximum.[citation needed] The Chilterns are part of a system of chalk downlands throughout eastern and southern England, formed between 65 and 95 million years ago,[2] comprising rocks of the Chalk Group; this also includes Salisbury Plain, Cranborne Chase, the Isle of Wight and the South Downs in the south. In the north, the chalk formations continue northeastwards across north Hertfordshire, Norfolk and the Lincolnshire Wolds, finally ending as the Yorkshire Wolds in a prominent escarpment, south of the Vale of Pickering. The beds of the Chalk Group were deposited over the buried northwestern margin of the Anglo-Brabant Massif during the Upper Cretaceous.[5] During this time, sources for siliciclastic sediment had been eliminated due to the exceptionally high sea level.[6] The formation is thinner through the Chiltern Hills than the chalk strata to the north and south and deposition was tectonically controlled, with the Lilley Bottom structure playing a significant role at times.[5] The Chalk Group, like the underlying Gault Clay and Upper Greensand, is diachronous.[6]

During the late stages of the Alpine Orogeny, as the African Plate collided with Eurasian Plate, Mesozoic extensional structures, such as the Weald Basin of southern England, underwent structural inversion.[5] This phase of deformation tilted the chalk strata to the southeast in the area of the Chiltern Hills. The gently dipping beds of rock were eroded, forming an escarpment.

The chalk strata are frequently interspersed with layers of flint nodules which apparently replaced chalk and infilled pore spaces early in the diagenetic history. Flint has been mined for millennia from the Chiltern Hills.[citation needed] They were first extracted for fabrication into flint axes in the Neolithic period, then for knapping into flintlocks. Nodules are to be seen everywhere in the older houses as a construction material for walls.

Physical characteristics

Topography

Ivinghoe Beacon (the eastern trailhead) seen looking north from The Ridgeway

The highest point is at 267 m (876 ft) above sea level at Haddington Hill near Wendover in Buckinghamshire; a stone monument marks the summit. The nearby Ivinghoe Beacon is a more prominent hill, although its altitude is only 249 m (817 ft).[7] It is the starting point of the Icknield Way Path and the Ridgeway long distance path, which follows the line of the Chilterns for many miles to the west, where they merge with the Wiltshire downs and southern Cotswolds. To the east of Ivinghoe Beacon is Dunstable Downs, a steep section of the Chiltern scarp. Near Wendover is Coombe Hill, 260 m (853 ft) above sea level. The more gently sloping country – the dip slope – to the southeast of the Chiltern scarp is also generally referred to as part of the Chilterns; it contains much beech woodland[1] and many villages.

Landscape and land use

Enclosed fields account for almost 66% of the "Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty" (AONB) area. The next most important, and archetypal, landscape form is woodland, covering 21% of the Chilterns, which is thus one of the most heavily wooded areas in England. Built-up areas (settlements and industry) make up over 5% of the land area; parks and gardens nearly 4%, open land (commons, heaths and downland) is 2%, and the remaining 2% includes a variety of uses, including communications, military, open land, recreation, utilities and water.[2]

Rivers

The Chilterns are almost entirely located within the Thames drainage basin, and also drain towards several major Thames tributaries, most notably the Lea, which rises in the eastern Chilterns, the Colne to the south, and the Thame to the north and west. Other rivers arising near the Chilterns include the Mimram, the Ver, the Gade, the Bulbourne, the Chess, the Misbourne and the Wye. These are classified as chalk streams, although the Lea is degraded by water from road drains and sewage treatment works.[8] The River Thames flows through a gap between the Berkshire Downs and the Chilterns. Portions of the northern and north-eastern Chilterns around Leighton Buzzard and Hitchin are drained by the Ouzel, the Flit and the Hiz, all of which ultimately flow into the River Great Ouse (the last two via the Ivel).

Transport routes

A number of transport routes pass through the Chilterns in natural or man-made corridors. There are also over 2,000 km (1,200 mi) of public footpaths in the Chilterns, including long-distance trackways such as the Icknield Way and The Ridgeway.[9] The M40 motorway passes through the Chilterns in Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire sections, with a deep cutting through the Stokenchurch Gap. The M1 motorway crosses the Bedfordshire section near Luton. Other major roads include the A413, the A41 and the A5.

Railways include the Chiltern Main Line via High Wycombe and Princes Risborough, and the London to Aylesbury Line via Amersham. Nearby the West Coast Main Line runs through Berkhamsted and the Midland Main Line with Thameslink calls at Luton. The Great Western Main Line and its branches such as the Henley and Marlow branch lines link the southern side of the Chilterns with London Paddington. The Chinnor and Princes Risborough Railway is a preserved line. In 2012 the UK Government announced that the proposed High Speed 2 rail route would pass through the Chilterns near Amersham, partly through tunnels and partly at surface level.[10]

Air corridors from Luton Airport pass over the Chilterns to the east and west of the airport.

There are no navigable rivers (apart from the River Thames), though the Grand Union Canal passes through the Chilterns between Berkhamsted and Marsworth following the course of the Colne, Gade, Bulbourne and (after crossing a watershed) the Ouzel. This canal has branches to Wendover and Aylesbury.

History

In pre-Roman times, the Chiltern ridge provided a relatively safe and easily navigable route across southern Iron Age England, thus the Icknield Way (one of England's ancient prehistoric trackways) follows the line of the hills.

Although the Tribal Hidage suggests the tribe gave its name to the hills, the truth must be the reverse since the toponym is of Brittonic origin. Eilert Ekwall suggested that "Chiltern" is possibly related to the ethnic name "Celt" ("Celtæ" in early Celtic). An adjective celto- ="high" with suffix -erno- could be the origin of Chiltern.[11]

One of the principal Roman settlements in the Roman province of Britannia Superior was sited at Verulamium (now St Albans) and there are significant Roman and Romano-British remains in the area.

The Tudors had a hunting lodge in the Hemel Hempstead area.

Settlement

Prior to the 18th century the population was dispersed across the predominantly rural landscape of the Chilterns, in remote villages, hamlets and farmsteads and small market towns along the main long-distance turnpike routes which funnelled through convenient valleys. The coming of canals in the 18th century and railways in the 19th century encouraged settlement and growth of many towns, e.g. High Wycombe, Tring and Luton. There was significant housing and industrial development in the first half of the 20th century and continued throughout the 20th century, e.g. in Amersham, Beaconsfield, Berkhamsted, Hitchin and Chesham. The growth in motor car use and improved rail transport to and from London has latterly put a premium on the availability and price of commuter housing.[3] In 2002 there were 100,000 people living within the AoNB area of the Chilterns.[9]

List of towns and villages in the Chiltern hills area

Watlington Town Hall from the south

Aldbury, Amersham, Apsley, Ashridge, Aylesbury

Barton-le-Clay, Bellingdon, Berkhamsted, Bledlow Ridge, Bovingdon, Bradenham, Breachwood Green, Buckland Common

Caddington, Chalfont St Giles, Chalfont St Peter, Chartridge, Checkendon, Chesham, Chiltern Green, Chinnor, Cholesbury, Christmas Common, Coleshill

Dagnall, Dunsmore, Dunstable

Edlesborough, Ellesborough

Fawley, Fingest, Flackwell Heath, Frieth

Gerrards Cross, Goring-On-Thames, Great Hampden, Great Kingshill, Great Missenden, Great Offley

Halton, Hambleden, Harlington, Hawridge, Hazlemere, Hemel Hempstead, Henley-on-Thames, Hexton, High Wycombe, Hitchin, Holmer Green, Hughenden

Ibstone, Ivinghoe, Jordans, Kensworth

Lacey Green, Lane End, Latimer Ley Hill, Lilley, Little Chalfont, Little Gaddesden, Little Kingshill, Little Missenden, Luton

Markyate, Marlow, Marlow Bottom, Medmenham

Naphill, Nettlebed, Nuffield, Oxfordshire

Penn, Pishill, Prestwood, Princes Risborough, Radnage, Redbourn

Seer Green, Sharpenhoe, Shiplake, Skirmett, Southend, Speen, St Leonards, Stokenchurch, Stonor, Streatley (Beds), Studham

Thame, The Lee, Tring, Turville, Tylers Green

Walter's Ash, Watlington, Wendover, West Wycombe, Whipsnade, Whitwell, Wigginton, Woodcote

Strip parishes associated with the Chilterns

The western edge of the Chilterns is notable for its ancient strip parishes, elongated parishes with villages in the flatter land below the escarpment and woodland and summer pastures in the higher land.[3]

- Bedfordshire: Eaton Bray, Toddington, Totternhoe

- Buckinghamshire: Aston Clinton, Aylesbury, Bledlow, Buckland, Drayton Beauchamp, Great Kimble, Horsenden, The Lee, Marsworth, Monks Risborough, Pitstone, Princes Risborough, Saunderton, Stoke Mandeville, Weston Turville

- Hertfordshire: Tring, Wigginton

- Oxfordshire: Aston Rowant, Checkendon, Chinnor, Ipsden, Lewknor, Mongewell, Newnham Murren, Nuffield, Pyrton, Shirburn, South Stoke, Watlington

Economic use

The hills have been exploited for their natural resources for millennia. The chalk has been quarried for the manufacture of cement, and flint for local building material. Beechwoods supplied furniture makers with quality hardwood.[1] The area was once (and still is to a lesser degree) renowned for its chair-making industry,[1] centred on the towns of Chesham and High Wycombe (the nickname of Wycombe Wanderers Football Club is the Chairboys). Water was and remains a scarce resource in the Chilterns. Historically it was drawn from the aquifer via ponds, deep wells, occasional springs or bournes and chalk streams and rivers. Today the chalk aquifer is exploited via a network of pumping stations to provide a public supply for domestic consumption, agriculture and business uses, both within and well-beyond the Chilterns area. Rivers such as the River Chess directly supply watercress beds. Over-exploitation has possibly led to the disappearance of some streams over at least long periods.[12]

Nettlebed's one remaining pottery kiln

In a region short of building stone, local clay deposits and timber provided the raw materials for brick manufacture. Where available, flint was also used for construction; it is still used in modern buildings, although restricted to decoration to give a vernacular appearance.

Mediaeval strip parishes reflected the diversity of land from clay farmland, through wooded slopes to downland. Their boundaries were often drawn to include a section of each type of land, resulting in an irregular county boundary between, say, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire. These have tended to be smoothed out by successive reorganisations.

In modern times, as people have come to appreciate open country, the area has become a visitor destination and the National Trust has acquired land to preserve its character, for example at Ashridge, near Tring. In places, with the reduction of sheep grazing, action has been taken to maintain open downland by suppressing the natural growth of scrub and birch woodland. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Youth Hostels Association established several youth hostels for people visiting the hills.

The hills have been used as a location for telecommunication relay stations such as Stokenchurch BT Tower and that at Zouches Farm.

Protection

The Chilterns is an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and so enjoys special protection from major developments, which should not take place in such areas except in exceptional circumstances. This protection applies to major development proposals that raise issues of national significance.[13] In 2000 the government confirmed that the landscape qualities of AONBs are equivalent to those of National Parks, and that the protection given to both types of area by the land use planning system should also be equivalent.

Chilterns Conservation Board

The Chilterns Conservation Board was established by Parliamentary Order in July 2004. It is an independent body comprising 27 members drawn from the relevant local authorities and from those living in local communities within the Chiltern AONB area.

The Board’s purposes are set out in Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000: In summary these are:- First, to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the AONB, and increase the understanding and enjoyment by the public of the special qualities of the AONB. Second, while taking account of the first purpose, to foster the economic and social wellbeing of local communities within the AONB. Third, to publish and promote the implementation of a management plan for the AONB.[14]

In contrast to National Parks, the Chilterns - as other AONBs - do not possess their own planning authority. The Board has an advisory role on planning and development matters and seeks to influence the actions of local government by commenting upon planning applications.[15]

The local authorities (four County Councils, one Unitary Authority and ten District and Borough Councils) are expected to respect the area's status as a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

High Speed Rail 2

In October 2010 the government confirmed proposals for the High Speed 2 rail link from London to Birmingham with a recommended route through the Chilterns AONB. The Conservation Board has made clear it is opposed to the routing of HS2 through the Chilterns AONB.[16]

Chiltern Hundreds

The Chilterns includes the Chiltern Hundreds. By established custom, Members of the British Parliament, who are prohibited from resigning their seats directly, may apply for the Stewardship of the Chiltern Hundreds as a device to enable their departure from the House (see Resignation from the House of Commons).

See also

- Zouches Farm

References

^ abcd Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 163..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 163..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ abc The Changing Landscape of the Chilterns Chilterns AoNB, Accessed 19 February 2012

^ abc Hepple, Leslie; Doggett, Alison (1971). The Chilterns. England: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-85033-833-6.

^ Chiltern Society, The Chilterns

^ abc Rawson, P.F. 2006. Cretaceous: sea levels peak as the North Atlantic opens. In: P.J. Brenchley and P.F. Rawson (Eds) The Geology of England and Wales, p.365-393. The Geological Society

ISBN 978-1-86239-200-7

^ ab Anderson, R., P.H. Bridges, M.R. Leeder and B.W. Sellwood (Eds) 1979. A Dynamic Stratigraphy of the British Isles: A Study in Crustal Evolution. p. 241. George Allen and Unwin, London.

ISBN 0-412-44510-7

^ "Natural England". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-06-24.

^ B.S. Nau, C. R. Boon, and J. P. Knowles, Bedfordshire Wildlife, Castlemead, 1987,

ISBN 0-948555-05-X, page 71.

^ ab DidYouKnow.pdf[permanent dead link] Chilterns AoNB, Accessed 19 February 2012

^ Chilerns AoNB website - HS2, Accessed 20 February 2012

^ Ekwall, Eilert (1940). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names (second ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 99. Ekwall cites the forms Cilternsætna (Birch's Cartularium Saxonicum; 297); Cilternes efes (Kemble's Codex diplomaticus aevi Saxonici; 715) and Ciltern (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle; text E)

^ Chess Valley Association, Accessed 4 September 2014

^ "Planning Policy Statement 7: Sustainable Development in Rural Areas" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-23. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

^ Chiltern Conservation Board - Our Role, Accessed 10 December 2012

^ Chilterns Conservation Board

^ Chilterns Conservation Board - statement objecting to HS2, Accessed 12 December 2012

External links

- Chilterns AONB

- Chilterns Conservation Board

- Chilterns Tourism Network

- Chiltern Society