Milice

| Milice française | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Milice | |

| Active | 30 January 1943 (1943-01-30)–15 August 1944 (1944-08-15) |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Type | Paramilitary |

| Role | Anti-partisan duties in Axis-controlled France |

| Size | 25,000–30,000 |

| March | Le Chant des Cohortes |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Joseph Darnand |

The Milice française (French Militia), generally called the Milice (French pronunciation: [milis]), was a political paramilitary organization created on 30 January 1943 by the Vichy regime (with German aid) to help fight against the French Resistance during World War II. The Milice's formal head was Prime Minister Pierre Laval, although its Chief of operations and de facto leader was Secretary General Joseph Darnand. It participated in summary executions and assassinations, helping to round up Jews and résistants in France for deportation. It was the successor to Joseph Darnand's Service d'ordre légionnaire (SOL) militia. The Milice was the Vichy regime's most extreme manifestation of fascism. Ultimately, Darnand envisaged the Milice as a fascist single party political movement for the French state.[1]

Members of the Milice, armed with captured British Bren guns and No. 4 Lee–Enfield rifles

The Milice frequently used torture to extract information or confessions from those whom they interrogated. The French Resistance considered the Milice more dangerous than the Gestapo and SS because they were native Frenchmen who understood local dialects fluently, had extensive knowledge of the towns and countryside, and knew local people and informants.

Contents

1 Membership

2 Symbols and materials

2.1 Emblem

2.2 March

2.3 Uniform

3 History

3.1 Beginnings

3.2 Reprisals

3.3 Notable actions

3.4 End of the war

3.5 Aftermath

4 In popular culture

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

Membership

Resistance members captured by the Milice, July 1944. One of the miliciens is armed with a captured British Sten gun.

Early Milice volunteers included members of France's pre-war far-right parties (such as the Action Française) and working-class men convinced of the benefits of the Vichy government's politics. In addition to ideology, incentives for joining the Milice included employment, regular pay and rations. (The latter became particularly important as the war continued, and civilian rations dwindled to near-starvation levels.) Some joined because members of their families had been killed or injured in Allied bombing raids or had been threatened, extorted or attacked by French Resistance groups. Still others joined for more mundane reasons: petty criminals were recruited by being told their sentences would be commuted if they joined the organization, and Milice volunteers were exempt from transportation to Germany as forced labour.[2] It is estimated by several historians (including Julian T. Jackson) that the Milice's membership reached 25,000–30,000 by 1944, although official figures are difficult to obtain. The majority of members were not full-time militiamen, but devoted only a few hours per week to their Milice activities.[3] The Milice had a section for full-time members, the Franc-Garde, who were permanently mobilized and lived in barracks.[3]

The Milice also had youth sections for boys and girls, called the Avant-Garde.[3]

Symbols and materials

Emblem

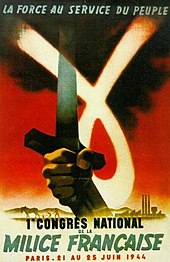

The chosen emblem for the Milice carried the Greek letter γ (gamma), the symbol of the Aries astrological sign in the Zodiac, ostensibly representing rejuvenation, and replenishment of energy. The color scheme chosen was silver in blue background within a red circle for ordinary miliciens, white in black background for the arm-carrying militants, and white in red background for the active combatants.

March

Their march was Le Chant des Cohortes.[4]

Uniform

Milice member guarding Resistance PoWs wearing a German Army Wound Badge (indicating previous service with a German Army unit) and armed with a Spanish copy of the Smith & Wesson Model 10 revolver, chambered in 8mm French Ordnance.

Milice troops (known as miliciens) wore a blue uniform jacket and trousers, brown shirt and a wide blue beret. (During active paramilitary-style operations, a pre-war French Army helmet was used.) Its newspaper was Combats (not to be confused with the underground Resistance newspaper, Combat). It employed full-time and part-time personnel, and had a youth wing. The Milice's armed forces were officially known as the Franc-Garde. Contemporary photographs show the Milice armed with a variety of weapons captured from Allied forces.

History

Beginnings

The Resistance targeted individual miliciens for assassination, often in public areas such as cafés and streets. On April 24, 1943, they shot and killed Paul de Gassovski, a milicien in Marseilles. By late November, Combat reported that 25 miliciens had been killed and 27 wounded in Resistance attacks.

Reprisals

The most prominent person killed by the Resistance was Philippe Henriot, the Vichy regime's Minister of Information and Propaganda, who was known as "the French Goebbels". He was killed in his apartment in the Ministry of Information on the rue Solferino in the predawn hours of June 28, 1944 by résistants dressed as miliciens. His wife, who was in the same room, was spared. The Milice retaliated for this by killing several well-known anti-Nazi politicians and intellectuals (such as Victor Basch) and prewar conservative leader Georges Mandel.

The Milice initially operated in the former Zone libre of France under the control of the Vichy regime. In January 1944, the radicalized Milice moved into what had been the zone occupée of France (including Paris). They established their headquarters in the old Communist Party headquarters at 44 rue Le Peletier and at 61 rue Monceau. (The house was formerly owned by the Menier family, makers of France's best-known chocolates.) The Lycée Louis-Le-Grand was occupied as a barracks, and an officer candidate school was established in the Auteuil synagogue.

Notable actions

Counterfeit Milices card prepared for French Resistance member Serge Ravanel, under the alias of Charles Guillemot

Perhaps the largest and best-known operation undertaken by the Milice was the Battle of Glières, its attempt in March 1944 to suppress the Resistance in the département of Haute-Savoie (in southeastern France, near the Swiss border).[5] The Milice could not overcome the Resistance, and had to call in German troops to complete the operation. On Bastille Day, 14 July 1944, miliciens suppressed a revolt among the prisoners at Paris' Santé prison.

The legal standing of the Milice was never clarified by the Vichy government; it operated parallel to (but separate from) the Vichy French police force. The Milice operated outside civilian law, and its actions were not subject to judicial review or control.

End of the war

In August 1944, as the tide of war was shifting and fearing he would be held accountable for the operations of the Milice, Marshal Philippe Pétain distanced himself from the organization by writing a harsh letter rebuking Darnand for the organization's excesses. Darnand's response suggested that Pétain ought to have voiced his objections sooner.

Historians have debated the strength of the organization, but it was probably between 25,000 and 35,000 (including part-time members and non-combatants) by the time of the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944. The membership began melting away rapidly thereafter. Following the Liberation of France, members who failed to flee to Germany (where they were impressed into the Charlemagne Division of the Waffen-SS) or elsewhere, generally faced imprisonment for treason, execution following courts-martial or murder by vengeful résistants and civilians. During a period of unofficial reprisals immediately following on the German retreat, large numbers of miliciens were executed, either individually or in groups. Milice offices throughout France were ransacked with agents often being brutally beaten and then thrown from office windows, or into rivers before being taken to prison. At Le Grand-Bornand 76 captured members of the Milice were executed by French Forces of the Interior on 24 August 1944.[6]

Aftermath

An unknown number of miliciens managed to escape prison or execution, either by going underground or fleeing abroad. A few were later prosecuted. The most notable of these was Paul Touvier, the former commander of the Milice in Lyon. In 1994, he was convicted of ordering the retaliatory execution of seven Jews at Rillieux-la-Pape. He died in prison two years later.

In popular culture

- Since the war, the term milice has acquired a derogatory meaning in France.

- The French hard rock ensemble Trust had a hit named "Police Milice", where its frontman Bernard Bonvoisin compared modern-day police officers to the Milice.

Louis Malle's films Lacombe, Lucien and Au revoir les enfants include the Milice as part of the plot.- The 2003 drama The Statement, directed by Norman Jewison and starring Michael Caine, was adapted from the 1996 novel by the same name by Brian Moore. He shaped it from the story of Paul Touvier, a Vichy French Milice official who hid for years (often sheltered by the Catholic Church) and was indicted in 1991 for war crimes.

- The film Female Agents (French: Les Femmes de l'ombre), set during World War II, has a scene where two of the female agents walk past a recruitment poster for the Milice which says "Against Communism / French Militia / Secretary-General Joseph Darnand".

- In the Doctor Who audio story Resistance, the Doctor and Polly have to evade the Milice in 1944.

- They feature prominently in the popular French TV series Un Village Français which covers the whole period of the occupation and liberation and was broadcast in France and extensively internationally.[1]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World War II France Milice. |

- Axis

Lorenzen Group – Danish pro-German paramilitary group

Security Battalions – Greek pro-German paramilitary group

Carlingue – the French equivalence of the Gestapo.

Special Brigades – Paramilitary sections of the Vichy Police service.

Geheime Feldpolizei – the secret military police of the Wehrmacht that worked alongside the Milice

- Allies

Maquis des Glières – resistance group

Maquis du Vercors – resistance group

References

^ Martin Blinkhorn, 2003, Fascists and Conservatives: The Radical Right and the Establishment in Twentieth-Century Europe, p. 193, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 1134997124

^ Paul Jankowski, "In Defense of Fiction: Resistance, Collaboration, and Lacombe, Lucien". The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 63, No. 3 (Sep., 1991), pp. 462

^ abc Matthew Feldman, 2004, Fascism: The 'fascist epoch', p. 243,

ISBN 0415290198

^ Michel Germain (1997). La Fontaine de Siloé, ed. [[[:Template:Google Livres]] Histoire de la milice et des forces du maintien de l'ordre en Haute-Savoie 1940-1945 – Guerre civile en Haute-Savoie] Check|url=value (help). Les Marches. p. 482 of 507. ISBN 978-2-84206-041-1. Retrieved 30 June 2017..

^ "Battle of Glieres", World at War

^ "The lost cemetery of Le Grand-Bornand". www.lefrancophoney.com. 23 August 2013.

Further reading

"Cullen, Stephen (2010) "Collaborationists in Arms: The Uniforms and Equipment of the Vichy Milice Francaise". The Armourer Militaria Magazine (100): 24–28. July–August 2010.

Cullen, Stephen (2008). Cohort of the Damned: Armed Collaboration in Wartime France – the Milice Francaise, 1943–45. Warwick: Allotment Hut Booklets.

Cullen, Stephen (March 2008). "Legion of the Damned: The Milice Francaise, 1943–45". Military Illustrated.

Pryce-Jones, David (1981). Paris in the Third Reich: A History of the German Occupation. London: Collins.

"Resistance in France". After the Battle (105). 1999.