Lwów Eaglets

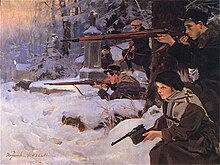

"Lwów Eaglets; Defenders of the Cemetery", painting by Wojciech Kossak, 1926, oil on canvas, 90 x 120 cm, Polish Army Museum, Warsaw

Lwów Eaglets (Polish: Orlęta lwowskie) is a term of affection applied to the Polish teenagers who defended the city of Lwów (Ukrainian: L'viv) in Eastern Galicia, during the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919).

Contents

1 Background

2 The Lwów Eaglets

3 Cemetery of the Lwów Eaglets

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Background

The city now known as the Ukrainian Lviv (Polish: Lwów) was before the breakdown of the Austro-Hungarian empire known as Lemberg, the capital of one of the Habsburg dominions, namely the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. Poles were the prevailing ethnic group in the province overall, but in the eastern Galician territories Ukrainians were a majority (65%), and Poles a significant minority (22%) dominating the cities along with Jews.[1] In Lemberg, according to the Austrian census of 1910, 51% of the city's population were Roman Catholics, 28% Jews, and 19% Ukrainian Greek Catholics. 86% of the city's population spoke Polish and 11% Ukrainian.[2]

In the final days of the collapsing Habsburg empire, on November 1, 1918, Ukrainian soldiers from Austrian army units occupied Lemberg's public buildings and military depots, raised Ukrainian flags throughout the city and proclaimed the birth of a new Ukrainian state. While the Ukrainian residents enthusiastically supported the proclamation, the city's significant Jewish minority remained mostly neutral towards it and the Polish residents, the majority of the city's inhabitants, were shocked to find themselves in a Ukrainian state.[3] Reacting to this military revolution, Poles rose up throughout the city. Polish forces, initially numbering only about 200, organized a small pocket of resistance in a school at the western outskirts, where a group of veterans of the Polish Military Organization put up a fight armed with 64 outdated rifles. After initial clashes, the defenders were joined by hundreds of volunteers, mostly boy scouts, students and youngsters. More than 1000 people joined the Polish ranks in the first day of the fighting.

The Lwów Eaglets

Among these were many young volunteers (such as Antoni Petrykiewicz), who became known as the Lwów Eaglets. Initially this term was confined to those who had participated in the fights within the city between November 1 and November 22, 1918, and the following siege by the Ukrainian army between November 23, 1918 and May 22, 1919. With time, however, the term's application was broadened, and it is now used for all the young soldiers who fought in the area of Eastern Galicia for the Polish cause in the Polish-Ukrainian War and the Polish-Bolshevik War. In addition to the young Polish nationals of Lviv, those fighting in the Polish-Ukrainian battle for Przemyśl are also frequently referred to as Przemyskie Orlęta ('"Przemyśl Eaglets").[4]

Cemetery of the Lwów Eaglets

Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów

After the Polish-Ukrainian conflict, the Lwów Eaglets were interred at the Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów (Polish popular name: Cmentarz Orląt Lwowskich), part of the Lychakiv Cemetery. The Cemetery of the Defenders held the remains of both teenaged and adult soldiers, including foreign volunteers from France and the United States. The Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów was designed by Rudolf Indruch, a student at the Lviv Institute of Architecture, himself an Eaglet. Among the most notable Eaglets to be buried there was 14-year-old Jerzy Bitschan, the youngest of the city's defenders, whose name became an icon of the Polish interbellum.

Also resting in the Eaglet's pantheon is six-year-old Oswald Anissimo who was executed together with his father Michał by the Ukrainian soldiers.[5]

After the annexation of Eastern Galicia with the city of Lwów by the Soviet Union in World War II (see: Soviet invasion of Poland) and the following expulsion of the Polish population from the city, the graves were destroyed in 1971, and the Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów was turned into a municipal waste dump and then into truck depot. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the formation of an independent Ukraine, work began on the restoration of the "Eaglets' Cemetery", although slowed by opposition of local nationalists. Following Polish support for Ukraine's Orange Revolution (2004), the opposition declined and the Cemetery was officially reopened in a Polish-Ukrainian ceremony on June 24, 2005. The last surviving Lwów Eaglet, Major Aleksander Sałacki (born 12 May 1904), died in Tychy, on April 5, 2008.

See also

- Battle of Lwów (1918)

- Battle of Zadwórze

- Leopold Lis-Kula

References

^ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press. pg. 123

^ New International Encyclopedia, Volume 13. 1915. Lemberg'.' pg. 760

^ Orest Subtelny, Ukraine: a history, pp. 367–368, University of Toronto Press, 2000, .mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

ISBN 0-8020-8390-0

^ "Obrona Przemyśla w 1918 roku" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

^ (in Polish) M. Gałęzowski, Na wzór Orląt lwowskich Archived 2014-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Biuletyn IPN, nr 11-12/2008, p. 99. Ukrainian military leader Dmytro Vitovsky threatened summary execution to all men living in houses from where shots were fired.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lwów Eaglets. |

- Official website

- Defenders of Lwow website

- With the Lwów Eaglets dear to their hearts, Orlęta, Polish Folk Song and Dance Group recreate an evening cafe scene in Lwów from the 1920s