Constitution of Spain

| Spanish Constitution | |

|---|---|

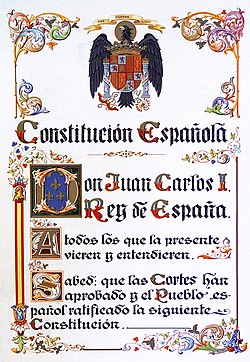

Original preface to the Spanish Constitution | |

| Created | 31 October 1978 |

| Ratified | 6 December 1978 |

| Date effective | 29 December 1978 |

| Location | Congress of Deputies |

| Author(s) | Fathers of the Constitution

|

| Signatories | Juan Carlos I |

Spain |

|---|

|

This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Spain |

Constitution

|

Monarchy

|

Legislature

|

Executive

|

Judiciary

|

Constitutional Court

|

Euro European Central Bank Bank of Spain

|

Administrative subdivisions

|

Elections

|

Foreign relations

|

Related topics

|

|

The Spanish Constitution (Spanish and Galician: Constitución Española; Basque: Espainiako Konstituzioa; Catalan: Constitució Espanyola; Occitan: Constitucion espanhòla) is the democratic law that is supreme in the Kingdom of Spain. It was enacted after its approval in a constitutional referendum, and it is the culmination of the Spanish transition to democracy. The Constitution of 1978 is one of about a dozen of other historical Spanish constitutions and constitution-like documents; however, it is one of two fully democratic constitutions (the other being the Spanish Constitution of 1931). It was sanctioned by King Juan Carlos I on 27 December, and published in the Boletín Oficial del Estado (the government gazette of Spain) on 29 December, the date in which it became effective. The promulgation of the constitution marked the culmination of the Spanish transition to democracy after the death of general Francisco Franco, on 20 November 1975, who ruled over Spain as a military dictator for nearly 40 years. This led to the country undergoing a series of political, social and historical changes that transformed the Francoist regime into a democratic state.

The Spanish transition to democracy was a complex process that gradually transformed the legal framework of the Francoist regime into a democratic state. The Spanish state didn't "abolish" the Francoist regime, but rather slowly transformed the institutions and approved and/or derogated laws so as to establish a democratic nation and approve the Constitution, all under the guidance of King Juan Carlos I of Spain. The Constitution was redacted, debated and approved by the constituent assembly (Spanish: Cortes .Constituyentes) that emerged from the 1977 general election. The Constitution then repealed all the Fundamental Laws of the Realm (the pseudo-constitution of the Francoist regime), as well as other major historical laws and every pre-existing law that contradicted what the Constitution establishes.

Article 1 of the Constitution defines the Spanish state. Article 1.1 states that "Spain is established as a social and democratic State, subject to the rule of law, which advocates as the highest values of its legal order the following: liberty, justice, equality and political pluralism. Article 1.2 refers to national sovereignty, which is vested in the Spanish people, "from whom the powers of the State emanate". Article 1.3 establishes parliamentary monarchy as the "political form of the Spanish state".

The Constitution is organized in ten parts (Spanish: Títulos) and an additional introduction (Spanish: Título Preliminar), as well as a preamble, several additional and interim provisions and a series of repeals, and it ends with a final provision. Part I refers to fundamental rights and duties, which receive special treatment and protection under Spanish law. Part II refers to the regulation of the Crown and lays out the King's role in the Spanish state. Part III elaborates on Spain's legislature, the Cortes Generales. Part IV refers to the Government of Spain, the executive power, and the Public Administration, which is managed by the executive. Part V refers to the relations between the Government and the Cortes Generales; as a parliamentary monarchy, the Prime Minister (Spanish: Presidente del Gobierno) is invested by the legislature and the Government is responsible before the legislature. Part VI refers to the organization of the judicial power, establishing that justice emanates from the people and is administered on behalf of the king by judges and magistrates who are independent, irrevocable, liable and subject to the rule of law only. Part VII refers to the principles that shall guide the economy and the finances of the Spanish state, subjecting all the wealth in the country to the general interest and recognizing public initiative in the economy, while also protecting private property in the framework of a market economy. It also establishes the Court of Accounts and the principles that shall guide the approval of the state budget. Part VIII refers to the "territorial organization of the State" and establishes a unitary state that is nevertheless heavily decentralized through delegation and transfer of powers. The result is a de facto federal model, with some differences from federal states. This is referred to as an autonomous state (Spanish: Estado Autonómico) or state of the autonomies (Spanish: Estado de las Autonomías). Part IX refers to the Constitutional Court, which oversees the constitutionality of all laws and protects the fundamental rights enshrined in Part I. Finally, Part X refers to constitutional amendments, of which there have been only two since 1978 (in 1995 and 2011).

Contents

1 Origins

2 Structure

2.1 Preamble

2.2 Preliminary Title

2.3 Part I: Fundamental rights and duties

2.4 Part II: The Crown

2.4.1 The refrendo

2.4.2 The King's functions in the Spanish state

2.4.3 Succession to the Crown

2.4.4 The Regency

2.5 Part III: The Cortes Generales

2.6 Part IV: The Government

2.7 Part V: The relations between the Cortes Generales and the Government

2.8 Part VI: The judiciary

2.9 Part VII: The economy and taxation

2.10 Part VIII: The territorial model

2.10.1 Article 143

2.10.2 Article 155

2.11 Part IX: The Constitutional Court

2.12 Part X: Constitutional amendments

3 Reform

3.1 Protected provisions

3.2 Reform of the autonomy statutes

4 Proposed amendments

4.1 The reform of the Senate

4.2 Other proposed amendments

5 See also

6 References

7 External links

Origins

The constitutional history of Spain dates back to the Constitution of 1812. After the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, a general election in 1977 convened the Constituent Cortes (the Spanish Parliament, in its capacity as a constitutional assembly) for the purpose of drafting and approving the constitution.

A seven-member panel was selected among the elected members of the Cortes to work on a draft of the Constitution to be submitted to the body. These came to be known, as the media put it, as the padres de la Constitución or "fathers of the Constitution". These seven people were chosen to represent the wide (and often, deeply divided) political spectrum within the Spanish Parliament, while the leading role was given to then ruling party and now defunct Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD).

Each of the Spanish parties had its recommendation to voters.

Gabriel Cisneros (UCD)

José Pedro Pérez-Llorca (UCD)

Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón (UCD)

Miquel Roca i Junyent (CDC)

Manuel Fraga Iribarne (AP)

Gregorio Peces-Barba (PSOE)

Jordi Solé Tura (PSUC)

The writer (and Senator by Royal appointment) Camilo José Cela later polished the draft Constitution's wording. However, since much of the consensus depended on keeping the wording ambiguous, few of Cela's proposed re-wordings were approved. One of those accepted was the substitution of the archaic gualda ("weld-colored") for the plain amarillo (yellow) in the description of the flag of Spain.[citation needed]

The constitution was approved by the Cortes Generales on 31 October 1978, and by the Spanish people in a referendum on 6 December 1978. 91.81% of voters supported the new constitution. Finally, it was sanctioned by King Juan Carlos on 27 December in a ceremony in the presence of parliamentarians. It came into effect on 29 December, the day it was published in the Official Gazette. Constitution Day on 6 December has since been a national holiday in Spain.

Structure

The Constitution recognizes the existence of nationalities and regions (Preliminary Title).

Preamble

Traditionally, writing the preamble to the constitution was considered an honour, and a task requiring great literary ability. The person chosen for this purpose was Enrique Tierno Galván. The full text of the preamble may be translated as follows:

.mw-parser-output .templatequote{overflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px}.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequotecite{line-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0}

The Spanish Nation, wishing to establish justice, liberty and security, and to promote the welfare of all who make part of it, in use of her sovereignty, proclaims its will to:

- Guarantee democratic life within the Constitution and the laws according to a just economic and social order.

- Consolidate a State ensuring the rule of law as an expression of the will of the people.

- Protect all Spaniards and all the peoples of Spain in the exercise of human rights, their cultures and traditions, languages and institutions.

- Promote the progress of culture and the economy to ensure a dignified quality of life for all

Establish an advanced democratic society, and

- Collaborate in the strengthening of peaceful and efficient cooperation among all the peoples of the Earth.

Consequently, the Cortes approve and the Spanish people ratify the following Constitution.

Preliminary Title

- Section 2. The Constitution is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation, the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards; it recognizes and guarantees the right to self-government of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed and the solidarity among them all.

As a result, Spain is now composed entirely of 17 Autonomous Communities and two autonomous cities with varying degrees of autonomy, to the extent that, even though the Constitution does not formally state that Spain is a federation (nor a unitary state), actual power shows, depending on the issue considered, widely varying grades of decentralization, ranging from the quasi-confederal status of tax management in Navarre and the Basque Country to the total centralization in airport management.

Part I: Fundamental rights and duties

Part II: The Crown

King Felipe's royal insignia.[1]

The Constitution dedicates its Part II to the regulation of the monarchy, which is referred to as The Crown (Spanish: La Corona). Article 56 of the Constitution establishes that the monarchy is the head of state and symbolizes the unity of the Spanish state. It refers to the monarch's role as a "moderator" whose main role is to oversee and ensure the regular functioning of the institutions. The King is also the highest-ranked representative of the Spanish state in international relations and only exercises the functions that are explicitly attributed to him by the Constitution and the laws. The King's official title is "King of Spain" (Spanish: Rey de España), but he is allowed to use any other titles that are associated to the Spanish Crown.

The King of Spain enjoys immunity and is not subject to legal responsibility. In a broad sense, this means that the King cannot be legally prosecuted.[2] Some jurists say that this only refers to criminal procedures, while others claim this immunity is also present in civil procedures; in practice, the King has never been prosecuted and it is unlikely that he would be prosecuted even if it was proven that the monarch had committed a crime. The legal justification for royal immunity is that the King is mandated by the Constitution to fulfill several roles as the head of state; thus, the King is obligated to perform his actions and fulfill his duties, so the King cannot be judged for actions that he is constitutionally obligated to perform.

The refrendo

The fact that the King is not personally responsible for his actions does not mean that his actions are not free of responsibility. The responsibility for the King's actions falls into the persons who hold actual political power and who actually take political decisions, which the King only formally and symbolically ratifies. This is done through a procedure or institution called the refrendo ("countersigning" in the official English translation of the constitution).

All the King's actions have to undergo the refrendo procedure. Through the refrendo, the responsibility of the King is transported to other persons, who will be responsible for the King's actions, if such responsibility is demanded from them. Article 64 explains the refrendo, which transports the King's responsibility unto the Prime Minister for most cases, though it also establishes the refrendo for Ministers in some cases. In general, when there is not a formed government, the responsibility is assumed by the President of the Congress of Deputies. Without the refrendo, the King's actions are null and void.

There are only two royal acts that do not require the refrendo. The first encompasses all acts related to the management of the Royal House of Spain; the King can freely hire and fire any employees of the Royal House and he receives an annual amount from the state budget to operate the Royal House, which he freely distributes across the institution. The second one refers to the King's will, which enables him to distribute his material legacy and name tutors for his children, if they are not legal adults.

The King's functions in the Spanish state

Article 62 of the Spanish Constitution establishes an exhaustive list of the King's functions, all of which are symbolic and do not reflect the exercise of any political power. The King sanctions and promulagtes the laws, which are approved by the Cortes Generales, which the King also symbolically and formally calls and dissolves. The King also calls for periodic elections and for referendums in the cases that are included by the laws or the Constitution.

The King also proposes a candidate for Prime Minister, which is probably the King's most 'political' function, as he traditionally holds meetings with the leaders of all the major political parties in order to facilitate the formation of a government. If a candidate is successfully invested by the Parliament, he formally names him Prime Minister of Spain. When a Prime Minister has been named, he also formally names all the members of his government, all of which are proposed by the Prime Minister himself. The King has both a right and a duty to be informed of all the state affairs; he is also allowed to preside over the government meetings when the Prime Minister invites him to do so, although he has the ability to reject this invitation.

Regarding the Government, the King also formally issues the governmental decrees, as well as bestowing all the civil and military ranks and employments, and he also grants honors and distinctions according to the laws. The King is also the supreme head of the Armed Forces of Spain, although the effective lead is held by the Government of Spain. Finally, the King holds the High Patronage of all the Royal Academies and other organizations that have a royal patronage.

Succession to the Crown

The succession to the Crown is regulated in article 57 which establishes a male preference primogeniture to the successors of King Juan Carlos I and his dynasty, the Bourbon dynasty. The heir to the throne receives the title of Prince or Princess of Asturias as well as the other historic titles of the heir and the other children received the title of Infates or Infantas.

If some person with rights of succession marries against the will of the King or Queen regnant or the Cortes Generales, shall be excluded from succession to the Crown, as shall their descendants. This article also establishes that if the lines are extinguished, the Cortes Generales shall decided who will be the new King or Queen attending to the general interests of the country.

Finally, the article 57.5 establish that abdications or any legal doubt about the succession must to be figure it out by an Organic Act.

This legal forecast was exercised for the first time of the current democratic period in 2014 when King Juan Carlos abdicated in his son. The Organic Act 3/2014 made efective the abdication of the King. A Royal decree of the same year also modified the Royal Decree of 1987 which establishes the titles of the Royal family and the Regents and arranged that the outgoing King and Queen shall conserve their titles. And the Organic Act 4/2014 modified the Organic Act of the Judiciary to allow the former Kings to conserve their judicial prerogatives (immunity).

The Regency

The Regency is regulated in article 59. The Regency is the period by which a person exercised the duties of King and Queen regnant in behalf of the real monarch that is a minor. This article establishes that the King or Queen's mother or father shall immediately assume the office of Regent and, in the absence of these, the oldest relative of legal age who is nearest in succession to the Crown.

Article 59 § 2 establishes that the monarch may be incapacitated by Parliament if becomes unfit for the exercise of his authority and the Prince or Princess of Asturias shall assume the regency if is on age, if is not, the previous procedure must to be followed.

If there is no person entitled to exercise the regency, the Cortes Generales shall appointed one regent or a council of three or five persons known as the Council of Regency. To be Regent it's needed to be Spaniard and legally of age.

The Constitution also established in article 60 that the guardian of the King or Queen during its minority can't be the same as the person who acts as regent unless it's the father, the mother or direct ancestors of the King. The parents can be guardians while they remain widowed. If they marry again they lost the guardianship and the Cortes Generales shall appointed a guardian which must comply with the same requirements as to be Regent.

Article 60 § 2 also establishes that the exercise of the guardianship is also incompatible with the holding of any office or political representation so that none person can be the guardian of the King while in a political office.

Part III: The Cortes Generales

Part IV: The Government

Part V: The relations between the Cortes Generales and the Government

Part VI: The judiciary

Part VII: The economy and taxation

Part VIII: The territorial model

Article 143

- Section 1. In the exercise of the right to self-government recognized in Article 2 of the Constitution, bordering provinces with common historic, cultural and economic characteristics, island territories and provinces with historic regional status may accede to self-government and form Autonomous Communities in conformity with the provisions contained in this Title and in the respective Statutes.

Monument to the Constitution of 1978 in Madrid

The Spanish Constitution is one of the few Bill of Rights that has legal provisions for social rights, including the definition of Spain itself as a "Social and Democratic State, subject to the rule of law" (Spanish: Estado social y democrático de derecho) in its preliminary title. However, those rights are not at the same level of protection as the individual rights contained in articles 14 to 28, since those social rights are considered in fact principles and directives of economic policy, but never full rights of the citizens to be claimed before a court or tribunal.

Other constitutional provisions recognize the right to adequate housing,[3]employment,[4]social welfare provision,[5]health protection[6] and pensions.[7]

Thanks to the political influence of Santiago Carrillo of the Communist Party of Spain, and with the consensus of the other "fathers of the constitution", the right to State intervention in private companies in the public interest and the facilitation of access by workers to ownership of the means of production were also enshrined in the Constitution.[8]

Article 155

- Section 1. If a self-governing community does not fulfil the obligations imposed upon it by the constitution or other laws, or acts in a way that is seriously prejudicial to the general interest of Spain, the government may take all measures necessary to compel the community to meet said obligations, or to protect the above-mentioned general interest.

- Section 2. With a view to implementing the measures provided for in the foregoing paragraph, the Government may issue instructions to all the authorities of the Self-governing Communities.

On Friday, October 27, 2017, the Senate of Spain (Senado) voted 214 to 47 to invoke Article 155 of the Spanish Constitution over Catalonia after the Catalan Parliament declared the independence. Article 155 powers gave Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy to remove secessionist politicians, including Carles Puigdemont, the Catalan leader and direct rule from Madrid.[9]

Part IX: The Constitutional Court

Part X: Constitutional amendments

Reform

The Constitution has been amended twice. The first time, Article 13.2, Title I was altered to extend to citizens of the European Union the right to active and passive suffrage (both voting rights and eligibility as candidates) in local elections. The second time, in August/September 2011, a balanced budget amendment and debt brake was added to Article 135.[10]

The current version restricts the death penalty to military courts during wartime, but the death penalty has since been removed from the Code of Military Justice and thus lost all relevance. Amnesty International has still requested an amendment to be made to the Constitution to abolish it firmly and explicitly in all cases.

Amnesty International Spain, Oxfam Intermón and Greenpeace launched a campaign in 2015[11] to amend the article 53 so that it extends the same protection to economic, social and cultural rights as to other rights like life or freedom.

After that, the campaign seeks another 24 amendments protecting human rights, the environment and social justice.

Protected provisions

Title X of the Constitution establishes that the approval of a new constitution or the approval of any constitutional amendment affecting the Preliminary Title, or Section I of Chapter II of Title I (on Fundamental Rights and Public Liberties) or Title II (on the Crown), the so-called "protected provisions", are subject to a special process that requires:

- that two-thirds of each House approve the amendment,

- that elections are called immediately thereafter,

- that two-thirds of each new House approves the amendment, and

- that the amendment is approved by the people in a referendum.

Curiously, Title X does not include itself among the "protected provisions" and, therefore, it would be possible, at least in theory, to first amend Title X using the normal procedure to remove or reduce severity of the special requirements, and then change the formerly protected provisions. Even though such a procedure would not formally violate the law, it could be considered an attack on its spirit. The same applies to Article 79 (3) of the German Basic Law which, while explicitly protecting certain parts of the constitution from being changed does not explicitly protect itself from being changed.

Reform of the autonomy statutes

The "Statutes of Autonomy" of the different regions are the second most important Spanish legal normatives when it comes to the political structure of the country. Because of that, the reform attempts of some of them have been either rejected or produced considerable controversy.

The plan conducted by the Basque president Juan José Ibarretxe (known as Ibarretxe Plan) to reform the status of the Basque Country in the Spanish state was rejected by the Spanish Cortes, on the grounds (among others) that it amounted to an implicit reform of the Constitution.

The People's Party attempted to reject the admission into the Cortes of the 2005 reform of the Autonomy Statute of Catalonia on the grounds that it should be dealt with as a constitutional reform rather than a mere statute reform because it allegedly contradicts the spirit of the Constitution in many points, especially the Statute's alleged breaches of the "solidarity between regions" principle enshrined by the Constitution. After failing to assemble the required majority to dismiss the text, the People's Party filed a claim of unconstitutionality against several dozen articles of the text before the Spanish Constitutional Court for them to be struck down.

The amended Autonomy Statute of Catalonia has also been legally contested by the surrounding Autonomous Communities of Aragon, Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community[12] on similar grounds as those of the PP, and others such as disputed cultural heritage. As of January 2008, the Constitutional Court of Spain has those alleged breaches and its actual compliance with the Constitution under judicial review.

Prominent Spanish politicians, mostly from the People's Party but also from the Socialist Party (PSOE) and other non-nationalist parties[citation needed], have advocated for the statutory reform process to be more closely compliant with the Constitution, on the grounds that the current wave of reforms threatens the functional destruction of the constitutional system itself. The most cited arguments are the self-appointed unprecedented expansions of the powers of autonomous communities present in recently reformed statutes:

- The amended version of the Catalan Statute prompts the State to allot investments in Catalonia according to Catalonia's own percentage contribution to the total Spanish GDP. The Autonomy Statute of Andalusia, a region that contributes less to Spain's GDP than the region of Catalonia contributes, requires it in turn to allocate state investments in proportion to its population (it is the largest Spanish Autonomous Community in terms of population). These requirements are legally binding, as they are enacted as part of Autonomy Statutes, which rank only below the Constitution itself. It is self-evident that, should all autonomous communities be allowed to establish their particular financing models upon the State, the total may add up to more than 100% and that would be unviable.[13] Despite these changes having been proposed and approved by fellow members of the PSOE, former Finance Minister Pedro Solbes disagreed with this new trend of assigning state investment quotas to territories based on any given autonomous community custom requirement[14] and has subsequently compared the task of planning the Spanish national budget to a sudoku.

- The Valencian statute, whose reform was one of the first to be enacted, includes the so-called Camps clause (named after the Valencian President Francisco Camps), which makes any powers assumed by other communities in its statutes automatically available to the Valencian Community.

- Autonomous communities such as Catalonia, Aragon, Andalusia or Extremadura, have included statutory clauses claiming exclusive powers over any river flowing through their territories. Nearby communities have filed complaints before the Spanish Constitutional Court on the grounds that no Community can exercise exclusive power over rivers that cross more than one Community, not even over the part flowing through its territory because its decisions affect other Communities, both downstream or upstream.

Proposed amendments

The reform of the Senate

Other proposed amendments

See also

- List of Constitutions of Spain

- Constitution

- Constitutional economics

- Constitutionalism

- Rule according to higher law

References

^ "Real Decreto 527/2014, de 20 de junio, por el que se crea el Guión y el Estandarte de Su Majestad el Rey Felipe VI y se modifica el Reglamento de Banderas y Estandartes, Guiones, Insignias y Distintivos, aprobado por Real Decreto 1511/1977, de 21 de enero" (PDF) (in Spanish). 21 June 2014. Retrieved 9 January 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output .citation q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .citation .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-ws-icon a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4c/Wikisource-logo.svg/12px-Wikisource-logo.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-maint{display:none;color:#33aa33;margin-left:0.3em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ "¿Cuán inmune es el Rey de España ante la justicia?" (in Spanish). 26 October 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

^ Article 47 of the Spanish Constitution states: "All Spaniards have the right to enjoy decent and adequate housing. The public authorities shall promote the necessary conditions and establish appropriate standards in order to make this right effective, regulating land use in accordance with the general interest in order to prevent speculation. The community shall have a share in the benefits accruing from the town-planning policies of public bodies".

^ Article 40 states: "The public authorities shall promote favourable conditions for social and economic progress and for a more equitable distribution of regional and personal income within the framework of a policy of economic stability. They shall in particular carry out a policy aimed at full employment."

^ Article 41 states: "The public authorities shall maintain a public Social Security system for all citizens guaranteeing adequate social assistance and benefits in situations of hardship, especially in case of unemployment. Supplementary assistance and benefits shall be optional."

^ Article 43 states: "The right to health protection is recognized. It is incumbent upon the public authorities to organize and watch over public health by means of preventive measures and the necessary benefits and services. The law shall establish the rights and duties of all in this respect."

^ Article 50 states: "The public authorities shall guarantee, through adequate and periodically updated pensions, a sufficient income for citizens in old age. Likewise, and without prejudice to the obligations of the families, they shall promote their welfare through a system of social services that provides for their specific problems of health, housing, culture and leisure."

^ "La elaboración de la Constitución", Miguel Herrero y Rodríguez de Miñón

^ "Catalonia's longest week". BBC News. 4 November 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

^ "Spain's main parties agree constitutional amendment capping public deficit". El Pais (in Spanish). 26 August 2011.

^ Blinda tus derechos. Official campaign site.

^ Admitidos los recursos de Aragón, Valencia y Baleares contra el Estatuto catalán. hoy.es

^ Solbes cuadra un sudoku de 23.000 millones · ELPAÍS.com

^ "Solbes rechaza vincular la nueva financiación a las balanzas fiscales", El País. 03/12/2007

External links

Wikisource has original text related to this article: Constitution of Spain |

Government of Spain website: The Spanish Constitution—(in English)

- RTVE video of the event of Juan Carlos I's sanction of the constitution in the presence of parliamentarians, 27 December 1978.

- The constitution on the Boletin Oficial del Estado's website