Birmingham, Alabama

| Birmingham, Alabama | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Birmingham | |||

From top left: Downtown from Red Mountain; Torii in the Birmingham Botanical Gardens; Alabama Theatre; Birmingham Museum of Art; City Hall; Downtown Financial Center | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): "The Magic City", "Pittsburgh of the South", "Bham" | |||

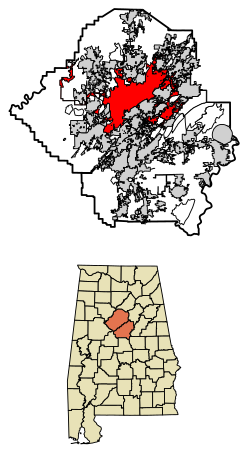

Location within Jefferson County and Shelby County | |||

Birmingham Location within Alabama Show map of Alabama  Birmingham Location within the United States Show map of the US | |||

| Coordinates: 33°39′12″N 86°48′32″W / 33.65333°N 86.80889°W / 33.65333; -86.80889Coordinates: 33°39′12″N 86°48′32″W / 33.65333°N 86.80889°W / 33.65333; -86.80889 | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Alabama | ||

| Counties | Jefferson, Shelby | ||

| Incorporated | December 19, 1871 | ||

| Named for | Birmingham, England, United Kingdom | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor–Council | ||

| • Mayor | Randall Woodfin | ||

| Area[1] | |||

| • City | 148.56 sq mi (384.78 km2) | ||

| • Land | 146.02 sq mi (378.19 km2) | ||

| • Water | 2.55 sq mi (6.59 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 644 ft (196 m) | ||

| Population (2010)[2] | |||

| • City | 212,237 | ||

| • Estimate (2017)[3] | 210,710 | ||

| • Rank | US: 107th AL: 1st | ||

| • Density | 1,443.04/sq mi (557.16/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 749,495 (US: 55th) | ||

| • Metro | 1,149,807 (US: 49th) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Birminghamian | ||

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) | ||

| ZIP Codes | 35201–35298 | ||

| Area code(s) | 205 | ||

| Interstates | I-20, I-22, I-59, I-65, and I-459 | ||

| Airports | Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport | ||

| FIPS code | 01-07000 | ||

GNIS feature ID | 015817 | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

Birmingham (/ˈbɜːrmɪŋhæm/ BUR-ming-ham) is a city located in the north central region of the U.S. state of Alabama. With an estimated 2017 population of 210,710, it is the most populous city in Alabama.[4] Birmingham is the seat of Jefferson County, Alabama's most populous and fifth largest county. As of 2017, the Birmingham-Hoover Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 1,149,807, making it the most populous in Alabama and 49th-most populous in the United States. Birmingham serves as an important regional hub and is associated with the Deep South, Piedmont, and Appalachian regions of the nation.

Birmingham was founded in 1871, during the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, through the merger of three pre-existing farm towns, most notably Elyton. The new city was named for Birmingham, England, the UK's second largest city and, at the time, a major industrial city. The Alabama city annexed smaller neighbors and developed as an industrial center, based on mining, the new iron and steel industry, and rail transport. Most of the original settlers who founded Birmingham were of English ancestry.[5] The city was developed as a place where cheap, non-unionized immigrant labor (primarily Irish and Italian), along with African-American labor from rural Alabama, could be employed in the city's steel mills and blast furnaces, giving it a competitive advantage over unionized industrial cities in the Midwest and Northeast.[6]:14

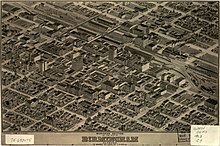

Panoramic map of Birmingham's business section from 1903

From its founding through the end of the 1960s, Birmingham was a primary industrial center of the southern United States. Its growth from 1881 through 1920 earned it nicknames such as "The Magic City" and "The Pittsburgh of the South". Its major industries were iron and steel production. Major components of the railroad industry, rails and railroad cars, were manufactured in Birmingham. Since the 1860s, the two primary hubs of railroading in the "Deep South" have been Birmingham and Atlanta. The economy diversified in the latter half of the 20th century. Banking, telecommunications, transportation, electrical power transmission, medical care, college education, and insurance have become major economic activities. Birmingham ranks as one of the largest banking centers in the U.S. Also, it is among the most important business centers in the Southeast.

In higher education, Birmingham has been the location of the University of Alabama School of Medicine (formerly the Medical College of Alabama) and the University of Alabama School of Dentistry since 1947. In 1969 it gained the University of Alabama at Birmingham, one of three main campuses of the University of Alabama System. It is home to three private institutions: Samford University, Birmingham-Southern College, and Miles College. The Birmingham area has major colleges of medicine, dentistry, optometry, physical therapy, pharmacy, law, engineering, and nursing. The city has three of the state's five law schools: Cumberland School of Law, Birmingham School of Law, and Miles Law School. Birmingham is also the headquarters of the Southwestern Athletic Conference and the Southeastern Conference, one of the major U.S. collegiate athletic conferences.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Founding and early growth

1.2 Birmingham civil rights movement

1.3 Recent history

2 Geography

2.1 Suburbs

2.2 Cityscape

2.3 Climate

2.4 Earthquakes

3 Demographics

3.1 Census data

3.1.1 2010

3.1.2 2000

3.2 Religion

3.3 Crime

4 Economy

5 Arts and culture

5.1 Museums

5.2 Festivals

5.3 Other attractions

5.4 Cultural references

6 Sports

7 Government

7.1 State and federal representation

7.2 Political controversy

8 Education

9 Media

10 Urban planning

11 Infrastructure

11.1 Transportation

11.1.1 Highways

11.1.2 Public transport

11.2 Utilities

12 Notable people

13 Sister cities

14 See also

15 Notes

16 References

17 Further reading

18 External links

History

Founding and early growth

L&N rail yard at Birmingham, ca. 1900

Birmingham was founded on June 1, 1871, by the Elyton Land Company, whose investors included cotton planters, bankers and railroad entrepreneurs. It sold lots near the planned crossing of the Alabama & Chattanooga and South & North Alabama railroads, including land that was formerly a part of the Benjamin P. Worthington plantation. The first business at that crossroads was the trading post and country store operated by Marre and Allen. The site of the railroad crossing was notable for its proximity to nearby deposits of iron ore, coal, and limestone – the three main raw materials used in making steel.

Child labor at Avondale Mills in Birmingham in 1910; photo by Lewis Hine

Birmingham is the only place where significant amounts of all three minerals can be found in close proximity.[7] From the start the new city was planned as a center of industry. The city's founders, organized as the Elyton Land Company, named it in honor of Birmingham, England, one of the world's premier industrial cities, to emphasize that point. The growth of the planned city was impeded by an outbreak of cholera and a Wall Street crash in 1873. Soon afterward, however, it began to develop at an explosive rate.

The Tennessee Coal and Iron Company (TCI) became the leading steel producer in the South by 1892. In 1907 U.S. Steel purchased it and became the most important political and economic force in Birmingham. It resisted new industry, however, to keep wage rates down.[6]:119

In 1911, the town of Elyton and several other surrounding towns were absorbed into Birmingham. From the early 20th century, the city grew so rapidly it earned the sobriquet "The Magic City". The downtown was redeveloped from a low-rise commercial and residential district into a busy grid of neoclassical mid- and high-rise buildings criss-crossed by streetcar lines. Between 1902 and 1912, four large office buildings were constructed at the intersection of 20th Street, the central north–south spine of the city, and 1st Avenue North, which connected the warehouses and industrial facilities along the east–west railroad corridor. This early group of skyscrapers was nicknamed the "Heaviest Corner on Earth".

Birmingham was hit by the 1916 Irondale earthquake (ML 5.1, intensity VII (Very strong)). A few buildings in the area were slightly damaged. The earthquake was felt as far as Atlanta and neighboring states.

While excluded from the best-paying industrial jobs, African Americans joined the migration of residents from rural areas to the city, drawn by economic opportunity.[citation needed]

The Great Depression of the 1930s struck Birmingham particularly hard, as the sources of capital fueling the city's growth rapidly dried up at the same time farm laborers, driven off the land, made their way to the city in search of work. Hundreds poured into the city, many riding in empty boxcars. "Hobo jungles" were established in Boyles, the Twenty-fourth Street Viaduct, Green Springs Bridge, East Thomas, Pratt City, Carbon Hill and Jasper.[8] In 1934, President Roosevelt called Birmingham the "worst-hit town in the country."[8]New Deal programs put many city residents to work in WPA and CCC programs, and they made important contributions to the city's infrastructure and artistic legacy, including such key improvements as Vulcan's tower and Oak Mountain State Park.

The World War II demand for steel followed by a post-war building boom spurred Birmingham's rapid return to prosperity. Manufacturing diversified beyond the production of raw materials. Major civic institutions such as schools, parks and museums, also expanded in scope.[9]

Despite the growing population and wealth of the city, Birmingham residents were markedly underrepresented in the state legislature. Although the state constitution required redistricting in accordance with changes in the decennial census, the state legislature did not undertake this at any time during the 20th century until the early 1970s, when forced by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark decision Reynolds v. Sims. Birmingham-area voters had sued to force redistricting, and the Court in its ruling cited the principle of "one man, one vote". The Court found that the geographic basis of the state senate, which gave each county one senator, gave undue influence to rural counties. Representatives of rural counties also had disproportionate power in the state House of Representatives, and had failed to provide support for infrastructure and other improvements in urban centers such as Birmingham, having little sympathy for urban populations. Prior to this time, the General Assembly ran county governments as extensions of the state through their legislative delegations.

Birmingham civil rights movement

In the 1950s and 1960s, Birmingham gained national and international attention as a center of activity during the Civil Rights Movement. Based on their members working in mining and industry, in the 1950s independent Ku Klux Klan (KKK) chapters had ready access to dynamite and other bomb materials. Whites unhappy with social changes in the 1950s committed racially motivated bombings of the houses of black families who moved into new neighborhoods or who were politically active, earning Birmingham the nickname "Bombingham".

Locally, the civil rights movement's activists were led by Fred Shuttlesworth, a fiery preacher who became legendary for his fearlessness in the face of such violence.[10] But he found city officials resistant to making changes for integration or lessening of Jim Crow.

16th Street Baptist Church, now a National Historic Landmark

A watershed in the civil rights movement occurred in 1963 when Shuttlesworth requested that Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which Shuttlesworth had co-founded, come to Birmingham to help end public segregation. King had served in Birmingham as a pastor earlier in his career.[11]

Together they launched "Project C" (for "Confrontation"), a massive non-violent demonstration against the Jim Crow system. While imprisoned in April 1963 for having taken part in a nonviolent protest, Dr. King wrote the now famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail", a defining treatise in his cause against segregation. During April and May, daily sit-ins and mass marches organized and led by movement leader James Bevel were met with police repression, tear gas, attack dogs, fire hoses, and arrests. More than 3,000 people were arrested during these protests, many of them children. King and Bevel filled the jails with students to keep the demonstrations going.

By September the SCLC and city were negotiating to end an economic boycott and desegregate stores and other facilities. On a Sunday in September 1963, a bomb went off at the 16th Street Baptist Church, killing four black girls.[12] The activists' protests and national outrage about the police and KKK violence contributed to the ultimate desegregation of public accommodations in Birmingham and also passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[13]

In 1998, the Birmingham Pledge, written by local attorney James Rotch, was introduced at the Martin Luther King Unity Breakfast. As a grassroots community commitment to combating racism and prejudice, it has since been used for programs in all fifty states and in more than twenty countries.[14]

Recent history

In the 1970s, urban renewal efforts focused around the development of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, which has become a major medical and research center. In 1971 Birmingham celebrated its centennial with a round of public-works improvements, including the upgrading of Vulcan Park and the construction of a major downtown convention center containing a 2,500-seat symphony hall, theater, 19,000-seat arena, and exhibition halls. Birmingham's banking institutions enjoyed considerable growth as well, and new skyscrapers were constructed in the city center for the first time since the 1920s. These projects helped the city's economy to diversify, but did not prevent the exodus of many of the city's residents to independent suburbs. Suburbanization was a national trend. In 1979 Birmingham elected Dr. Richard Arrington Jr. as its first African-American mayor.

Birmingham skyline at night from atop the City Federal Building, July 1, 2015

The population inside Birmingham's city limits has fallen over the past few decades, due in large part to "white flight" from the city to the surrounding suburbs and loss of jobs following industrial and railroad restructuring. The city's formerly most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white,[15] has declined from 57.4 percent in 1970 to 21.1 percent in 2010.[16] From 340,887 in 1960, the city's total population had decreased to 242,820 in 2000, a loss of about 29 percent. By 2010, Birmingham's population had reached 212,237, its lowest since the mid-1920s, but the city has since stopped losing residents.[17] That same period saw a corresponding rise in the populations of the suburban communities of Hoover, Vestavia Hills, Alabaster, and Gardendale, none of which was incorporated as a municipality until after 1950.

Downtown Birmingham is experiencing a renaissance. New resources have been dedicated in reconstructing the downtown area into a 24-hour mixed-use district. The market for downtown lofts and condominiums has increased, while restaurant, retail and cultural options have expanded. In 2006, the visitors bureau selected "the diverse city" as a new tag line for the city.[18] In 2011, the Highland Park neighborhood of Birmingham was named as a 2011 America's Great Place by the American Planning Association.[19] In January 2015, the International World Game Executive Committee selected Birmingham as the host for the 2021 World Games.[20]

Recent developments have attracted national media. The New York Times has praised the city's food scene since 2006.[21][22][23]The Washington Post has also featured stories about the city's cuisine and neighborhoods.[24] Referring to the city's civil rights history, Alice Short of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "Anyone who cares about U.S. history should plan a trip here."[25]

Geography

Birmingham occupies Jones Valley, flanked by long parallel mountain ridges (tailing ends of the Appalachian Mountains) running from northeast to southwest. The valley is drained by small creeks (Village Creek, Valley Creek) which flow into the Black Warrior River. The valley was bisected by the principal railroad corridor, along which most of the early manufacturing operations began.

Red Mountain lies immediately south of downtown. Many of Birmingham's television and radio broadcast towers are lined up along this prominent ridge. The "Over the Mountain" area, including Shades Valley, Shades Mountain and beyond, was largely shielded from the industrial smoke and rough streets of the industrial city. This is the setting for Birmingham's more affluent suburbs of Mountain Brook, Vestavia Hills, Homewood, and Hoover. South of Shades Valley is the Cahaba River basin, one of the most diverse river ecosystems in the United States.

Sand Mountain, a lower ridge, flanks the city to the north and divides Jones Valley from much more rugged land to the north. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad (now CSX Transportation) enters the valley through Boyles Gap, a prominent gap in the long low ridge.

Ruffner Mountain, located due east of the heart of the city, is home to Ruffner Mountain Nature Preserve, one of the largest urban nature reserves in the U.S.

Birmingham is 147 miles (237 km) west of Atlanta, 92 miles (148 km) north of Montgomery, 147 miles (237 km) northeast of Meridian, Mississippi, 239 miles (385 km) southeast of Memphis, 192 miles (309 km) south of Nashville, and 148 miles (238 km) southwest of Chattanooga,[26] all via Interstate highways.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 148.6 square miles (384.9 km2), of which 146.1 square miles (378.3 km2) are land and 2.5 square miles (6.6 km2), or 1.71%, are water.[2]

Suburbs

Birmingham has numerous suburbs. As with many major areas, most of the metropolitan population lives outside the city boundaries. In 2007, the metropolitan area was made up of 7 counties, 102 cities, and 21 school districts.[27] Since then Alabaster and Pelham have broken away from the Shelby County School System to form their own school systems. Some analysts argue that the region suffers from having so many suburbs; companies play jurisdictions against each other to gain tax and other financial incentives for relocation, resulting in no net gain in the area's economy.[28]

Suburbs in the Birmingham–Hoover metropolitan area by order of population (2016 estimates):

Hoover: Pop. 84,978

Vestavia Hills: Pop. 34,688

Alabaster: Pop. 32,948

Bessemer: Pop. 26,511

Homewood: Pop. 25,613

Pelham: Pop. 23,050

Trussville: Pop. 21,422

Mountain Brook: Pop. 20,590

Helena: Pop. 18,673

Center Point: Pop. 16,496

Hueytown: Pop. 15,561

Jasper: Pop. 14,003

Gardendale: Pop. 13,783

Calera: Pop. 13,489

Moody: Pop. 12,823

Irondale: Pop. 12,359

Chelsea: Pop. 12,341

Leeds: Pop. 11,940

Fairfield: Pop. 10,807

Pleasant Grove: Pop. 10,177

Forestdale: Pop. 10,162

Clay: Pop. 9,587

Fultondale: Pop. 9,084

Clanton: Pop. 8,846

Pinson: Pop. 7,426

Montevallo: Pop. 6,723

Oneonta: Pop. 6,699

Cityscape

| Name | Stories | Height |

|---|---|---|

| Wells Fargo Tower | 34 | 454 feet (138 metres) |

| Regions-Harbert Plaza | 32 | 437 feet (133 metres) |

| AT&T City Center | 30 | 390 feet (120 metres) |

| Regions Center | 30 | 390 feet (120 metres) |

| City Federal Building | 27 | 325 feet (99 metres) |

| Alabama Power Headquarters Building | 18 | 322 feet (98 metres) |

| Thomas Jefferson Tower | 20 | 287 feet (87 metres) |

| John Hand Building | 20 | 284 feet (87 metres) |

| Daniel Building | 20 | 283 feet (86 metres) |

Climate

Birmingham has a humid subtropical climate, characterized by hot summers, mild winters, and abundant rainfall. January has a daily mean temperature of 43.8 °F (6.6 °C), and there is an average of 47 days annually with a low at or below freezing, and 1.4 where the high does not surpass freezing.[29] July has a daily mean temperature of 81.1 °F (27.3 °C); highs reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on 55 days per year and 100 °F (38 °C) on 2 or 3.[29] Precipitation is relatively well-distributed throughout the year, with March the wettest month on average, and October the driest. Snow occasionally falls during winter, but many winters pass with no snow or only a trace. However, 10.3 inches (26.2 cm) fell on March 13, 1993, during the 1993 Storm of the Century, which established the highest daily snowfall, one-storm, and winter season total on record. Average snowfall over the winter season, based on the 1981–2010 period, is 1.6 in (4.1 cm), but, for the same period, median monthly snowfall for each month was zero.[29]

The spring and fall months are pleasant but variable as cold fronts frequently bring strong to severe thunderstorms and occasional tornadoes to the region. The fall season (primarily October) features less rainfall and fewer storms, as well as lower humidity than the spring, but November and early December represent a secondary severe weather season. Birmingham is located in the heart of a Tornado Alley known as the Dixie Alley due to the high frequency of tornadoes in Central Alabama. The greater Birmingham area has been hit by two F5 tornadoes; one in Birmingham's northern suburbs in 1977, and second in the western suburbs in 1998. The area was hit by an EF4 tornado which was part of the 2011 Super Outbreak. In late summer and fall months, Birmingham experiences occasional tropical storms and hurricanes due to its proximity to the Central Gulf Coast.

The record high temperature is 107 °F (42 °C), set on July 29, 1930,[30] and the record low is −10 °F (−23 °C), set on February 13, 1899.[31]

| Climate data for Birmingham Int'l, Alabama (1981–2010 normals,[a] extremes 1895–present)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 81 (27) | 83 (28) | 90 (32) | 92 (33) | 99 (37) | 106 (41) | 107 (42) | 105 (41) | 106 (41) | 94 (34) | 88 (31) | 80 (27) | 107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.1 (21.7) | 75.1 (23.9) | 82.0 (27.8) | 85.9 (29.9) | 90.4 (32.4) | 94.7 (34.8) | 97.2 (36.2) | 97.3 (36.3) | 94.0 (34.4) | 86.5 (30.3) | 79.3 (26.3) | 72.0 (22.2) | 99.0 (37.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53.8 (12.1) | 58.4 (14.7) | 66.7 (19.3) | 74.4 (23.6) | 81.5 (27.5) | 87.7 (30.9) | 90.8 (32.7) | 90.6 (32.6) | 85.1 (29.5) | 75.3 (24.1) | 65.4 (18.6) | 55.9 (13.3) | 73.8 (23.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 33.8 (1) | 37.1 (2.8) | 43.7 (6.5) | 50.5 (10.3) | 59.7 (15.4) | 67.7 (19.8) | 71.4 (21.9) | 70.8 (21.6) | 64.3 (17.9) | 52.9 (11.6) | 43.5 (6.4) | 36.3 (2.4) | 52.6 (11.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.5 (−9.7) | 18.7 (−7.4) | 24.7 (−4.1) | 32.9 (0.5) | 44.0 (6.7) | 55.7 (13.2) | 63.2 (17.3) | 62.0 (16.7) | 47.6 (8.7) | 35.0 (1.7) | 26.1 (−3.3) | 17.5 (−8.1) | 10.7 (−11.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) | −10 (−23) | 2 (−17) | 26 (−3) | 36 (2) | 42 (6) | 51 (11) | 51 (11) | 37 (3) | 27 (−3) | 5 (−15) | 1 (−17) | −10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.84 (122.9) | 4.53 (115.1) | 5.23 (132.8) | 4.38 (111.3) | 4.99 (126.7) | 4.38 (111.3) | 4.80 (121.9) | 3.93 (99.8) | 3.90 (99.1) | 3.44 (87.4) | 4.85 (123.2) | 4.45 (113) | 53.72 (1,364.5) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.6 (1.5) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (0.3) | 1.6 (4.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.5 | 10.0 | 10.2 | 9.1 | 10.2 | 11.0 | 11.7 | 9.6 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 116.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.5 | 66.5 | 64.2 | 65.0 | 70.1 | 71.6 | 74.4 | 74.6 | 74.0 | 71.6 | 71.4 | 71.2 | 70.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149.8 | 159.8 | 219.1 | 247.6 | 282.6 | 280.7 | 264.3 | 260.7 | 223.8 | 231.9 | 166.3 | 154.4 | 2,641 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 47 | 52 | 59 | 63 | 66 | 65 | 60 | 63 | 60 | 66 | 53 | 50 | 59 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990),[29][32][33][34] Weather.com[35] | |||||||||||||

Earthquakes

The Birmingham area is not prone to frequent earthquakes; its historical activity level is 59% less than the US average.[36] Earthquakes are generally minor and the Birmingham area can feel an earthquake from the Eastern Tennessee Seismic Zone. The magnitude 5.1 Irondale earthquake in 1916 caused damage in the Birmingham area and was felt in the neighboring states and as far as the Carolinas.[37] The 2003 Alabama earthquake centered in northeastern Alabama (magnitude 4.6–4.9) was also felt in the rest of Alabama, as well as Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 3,086 | — | |

| 1890 | 26,178 | 748.3% | |

| 1900 | 38,415 | 46.7% | |

| 1910 | 132,685 | 245.4% | |

| 1920 | 178,806 | 34.8% | |

| 1930 | 259,678 | 45.2% | |

| 1940 | 267,583 | 3.0% | |

| 1950 | 326,037 | 21.8% | |

| 1960 | 340,887 | 4.6% | |

| 1970 | 300,910 | −11.7% | |

| 1980 | 284,413 | −5.5% | |

| 1990 | 265,968 | −6.5% | |

| 2000 | 242,840 | −8.7% | |

| 2010 | 212,237 | −12.6% | |

| Est. 2017 | 210,710 | [3] | −0.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[38] 2017 Estimate[39] | |||

Census data

2010

According to the 2010 census:[15]

- 73.4% Black/African American

- 22.3% White

- 0.2% Native American

- 1.0% Asian

- 0.04% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- 1.0% Two or more races

- 2.0% Other races

- 3.6% Hispanic or Latino (of any race)

Map of racial distribution in Birmingham, 2010 U.S. Census. Each dot is 25 people: White, Black, Asian, Hispanic or Other (yellow)

2000

Based on the 2000 census, there were 242,820 people, 98,782 households, and 59,269 families residing in the city.[40] The population density was 1,619.7 people per square mile (625.4/km2). There were 111,927 housing units at an average density of 746.6 per square mile (288.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 62.46% Black, 35.07% White, 0.17% Native American, 0.80% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.62% from other races, and 0.83% from two or more races. 1.55% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 98,782 households out of which 27.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 31.1% were married couples living together, 24.6% had a female householder with no husband present, and 40.0% were non-families. 34.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 10.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.

In the city, the population is spread out, with 25.0% under the age of 18, 11.1% from 18 to 24, 30.0% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 13.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,898, and the median income for a family was $38,776. Males had a median income of $36,031 versus $30,367 for females. The city's per capita income was $19,962. About 22.5% of families and 27.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 41.9% of those under the age of 18 and 18.3% of those age 65 or over.[41]

Religion

St. Paul's Cathedral in downtown Birmingham

Birmingham has hundreds of Christian churches, five synagogues, three mosques, and two Hindu temples. The Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies published data showing that in 2010, among metro areas with greater than one million population, Birmingham had the second highest ratio of Christians, and the greatest ratio of Protestant adherents, in the U.S.[42][43]

The Southern Baptist Convention has 673 congregations and 336,000 members in the Birmingham metro area. The United Methodists have 196 congregations and 66,759 members. The headquarters of the Presbyterian Church in America was in Birmingham until the early 1980s; the PCA has more than 30 congregations and almost 15,000 members in the Birmingham metro area, with megachurches such as Briarwood Presbyterian Church. The National Baptist Convention has 126 congregations and 69,800 members.[44]

The city is home to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Birmingham, covering 39 counties and comprising 75 parishes and missions as well as seven Catholic high schools and nineteen elementary schools.[45] There are also two Eastern Catholic parishes in the Birmingham area. The Catholic television network EWTN is headquartered in metropolitan Birmingham. There are three Eastern Orthodox churches in the metro area, along with Greek, Russian, and American Orthodox churches. The mother church of the Episcopal Diocese of Alabama, the Cathedral Church of the Advent is located in downtown Birmingham. There is also a Unitarian Universalist church.

Crime

With a crime rate of 85 per one thousand residents, Birmingham has one of the highest crime rates in the United States, ranked 20th, according to a study in 2017 for cities with a population over 25,000. Neighboring Bessemer also ranks high at 7th.[46] Violent crime in Birmingham increased by 10% from 2014 to 2016. As the third most violent city in the country, the city's murder, robbery, and aggravated assault rates are each among the top five of all major U.S. cities. As in many high crime areas, poverty is relatively common in Birmingham. Citywide, 31% of residents live in poverty, a higher poverty rate than that of all but a dozen other large U.S. cities.[47]

Birmingham was ranked 425th in crime rate in the U.S. for 2012 by CQ Press.[48] The Birmingham-Hoover Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) was ranked as having the 35th highest crime rate in the U.S., out of 347 MSAs ranked in 2011 by CQ Press.[49] The Birmingham metro area crime rate is in line with other southern MSAs such as Jacksonville and Charlotte.[50]U.S. News & World Report ranked Birmingham as the third most dangerous city in the nation for 2011 (only Atlanta and St. Louis were ranked higher).[51] The A&E Network series The First 48 has filmed episodes with some of the city's homicide detectives.[citation needed]

Economy

From Birmingham's early days onward, the steel industry has always played a crucial role in the local economy. Though the steel industry no longer holds the same prominence that it once did in Birmingham, steel production and processing continue to play a key role in the economy. Steel products manufacturers American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO) and McWane are based in the city. Several of the nation's largest steelmakers, including CMC Steel, U.S. Steel, and Nucor, also have a major presence in Birmingham. In recent years, local steel companies have announced about $100 million worth of investment in expansions and new plants in and around the city. Vulcan Materials Company, a major provider of crushed stone, sand, and gravel used in construction, is also based in Birmingham.[52]

In the 1970s and 1980s, Birmingham's economy was transformed by investments in biotechnology and medical research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and its adjacent hospital. The UAB Hospital is a Level I trauma center providing health care and breakthrough medical research. UAB is now the area's largest employer and the second largest in Alabama, with a workforce of about 23,000 as of 2016[update].[53] Health care services providers Encompass Health (formerly HealthSouth), Surgical Care Affiliates and Diagnostic Health Corporation are also headquartered in the city. Caremark Rx was founded in the city.

Birmingham is a leading banking center, serving as home to two major banks: Regions Financial Corporation and BBVA Compass. SouthTrust, another large bank headquartered in Birmingham, was acquired by Wachovia in 2004. The city still has major operations as one of the regional headquarters of Wachovia, which itself is now part of Wells Fargo. In November 2006, Regions Financial merged with AmSouth Bancorporation, which was also headquartered in Birmingham. They formed the eighth largest U.S. bank by total assets. Nearly a dozen smaller banks are also headquartered in the Magic City, such as Superior Bank and Cadence Bank. As of 2009[update], the finance and banking sector in Birmingham employed 1,870 financial managers, 1,530 loan officers, 680 securities commodities and financial services sales agents, 380 financial analysts, 310 financial examiners, 220 credit analysts, and 130 loan counselors.[54] While Birmingham has seen major change-ups with its banking industry, it was still the ninth largest banking hub in the United States by the amount of locally headquartered deposits in 2012.[55] A 2014 study found that the city had moved down a spot to the tenth largest banking center.[56]

AT&T City Center in downtown

The telephone company that is now owned by AT&T, which was formerly BellSouth and before that South Central Bell, which had its headquarters in Birmingham, has a major nexus in Birmingham, supported by a skyscraper downtown as well as several large operational center buildings and a data center.

The insurance companies Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Alabama, Protective Life, Infinity Property & Casualty, ProAssurance, and Liberty National have their headquarters in Birmingham, and these employ a large number of people in Greater Birmingham.

Birmingham is also a powerhouse of construction and engineering companies, including BE&K, Brasfield & Gorrie, Walter Schoel Engineering Co. and B.L. Harbert International, which routinely are included in the Engineering News-Record lists of top design and international construction firms.[57][58]

Two of the largest soft-drink bottlers in the United States, each with more than $500 million in sales per year, are located in Birmingham. The Buffalo Rock Company, founded in 1901, was formerly a maker of just ginger ale, but now it is a major bottler for the Pepsi Cola Company. The Coca-Cola Bottling Company United, founded in 1902, is the third-largest bottler of Coca-Cola products in the United States.

Birmingham has seen a noticeable decrease in the number of Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the city, due to mergers, moves, and buy-outs. In 2000, there were ten Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the city, while in 2014 there was only one, Regions Bank. Birmingham also used to be home to more than 30 publicly traded companies, but in 2011 there were only 15.[59] The number has increased since then, but not significantly. Some companies, like Zoës Kitchen, were founded and operated in Birmingham, but moved their headquarters prior to going public,[60] even after saying they would stay in their home state.[61] Birmingham has been on a rebound, though, with the growth of companies like HealthSouth, Infinity Property and Casualty Corp.,[62]Southern Company, and others.

The Birmingham metropolitan area has consistently been rated as one of America's best places to work and earn a living based on the area's competitive salary rates and relatively low living expenses. One study published in 2006 by Salary.com determined that Birmingham was second in the nation for building personal net worth, based on local salary rates, living expenses and unemployment rates.[63]

A 2006 study by website bizjournals.com[64] calculated Birmingham's "combined personal income" (the sum of all money earned by all residents of an area in a year) at $48.1 billion.[65]

Birmingham's sales tax, which also applies fully to groceries, stands at 10 percent and is the highest tax rate of the nation's 100 largest cities.[66][67]

Although Jefferson County's bankruptcy filing in 2011 was the largest government bankruptcy in U.S. history, Birmingham remains solvent.[68]

In 2017, Birmingham's largest public companies by market capitalization were Vulcan Materials (VMC, $17.63 billion), Regions Bank (RF, $16.17 billion), Medical Properties Trust (MPW, $4.91 billion), Energen (EGN, $4.6 billion), and HealthSouth (HLS, $4.35 billion).[69] All were listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Protective Life was bought by the Japanese company Dai-Ichi in 2015 and removed from public trading. If Alabama Power was considered independent of the Southern Company (headquartered in Atlanta), it would be the second largest company in Birmingham with more than $5.8 billion in revenue in 2015.[70]

In 2017, Birmingham's largest private companies by annual revenue and employees were EBSCO Industries ($2.8 billion; 1,436 employees), Brasfield & Gorrie, LLC ($2.4 billion; 920 employees), Drummond Co, Inc. ($2.2 billion; 1,283 employees), O'Neal Industries ($2.1 billion; 275 employees), and McWane Inc. ($1.7 billion, 575 employees).[71]

Arts and culture

Alabama Theatre

Birmingham has a distinctly Deep South culture and a dynamic Upper South influence that has molded its culture from its beginning. This is due to the city's location as the gateway opening to and from both regions and their influences.[citation needed] Historically, many African Americans from the Black Belt and Whites from across the state settled this area in large numbers in the 20th century pursuing jobs in the steel industry, contributing their music and foods to its Southern nature.[72] In the 1970s the city began to diversify spurred on by the growth of the University of Alabama at Birmingham which attracted many students from out of state as well as international students. During this period Birmingham solidified itself as the most diverse city in Alabama and the hub of a growing multi-cultural metropolitan area. This blending of southern cultures with international flavors is most evident in the city's cosmopolitan Southside neighborhood. As the city's hub for bohemian culture and a long frequented nightlife area it is among the most popular and fastest growing in the city. Due to the presence of UAB it is the most racially and ethnically diverse neighborhood in the city.[citation needed]

Birmingham is the cultural and entertainment capital of Alabama, with numerous art galleries in the area including the Birmingham Museum of Art, the largest art museum in the Southeast. Downtown Birmingham is currently experiencing a cultural and economic rejuvenation, with several new independent shops and restaurants opening in the area. Birmingham is home to the state's major ballet, opera and symphony orchestra companies such as the Alabama Ballet,[73]Alabama Symphony Orchestra, Birmingham Ballet, Birmingham Concert Chorale, and Opera Birmingham.

- The historic Alabama Theatre hosts film screenings, concerts and performances.

° The historic Lyric Theatre, which was completely renovated and reopened in 2016, hosts performing arts shows and concerts.

- The Alys Robinson Stephens Performing Arts Center is home to the Alabama Symphony Orchestra and Opera Birmingham as well as several series of concerts and lectures. It is located on the campus of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- The Birmingham–Jefferson Convention Complex (BJCC) houses a theater, concert hall, exhibition halls, and a sports and concert arena. The BJCC is home to the Birmingham Children's Theatre,[74] one of the oldest and largest children's theatres in the country, and hosts major concert tours and sporting events. Adjacent to the BJCC is the Sheraton Birmingham, the largest hotel in the state. A new Westin Hotel anchors the nearby Uptown entertainment district of downtown Birmingham, which opened in 2013.[75]

- The historic Carver Theatre, home of the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame, offers concerts, plays, jazz classes (free to any resident of the state of Alabama) and many other events in the Historic 4th Avenue District, near the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

- The Birmingham Public Library, the downtown hub of a 40-branch metro library system, presents programs for children and adults.

Boutwell Memorial Auditorium (formerly Municipal Auditorium) is located at Linn Park.

Oak Mountain Amphitheatre is a large outdoor venue with two stages, located in the suburb of Pelham just south of Birmingham.

Other entertainment venues in the area include:

- Red Mountain Theater Company[76] is a local regional theater in Birmingham founded in 1979. The theater puts on a season of professional musical theater repertoire through the summer and fall annually. It received national notice for the company's performance of Newsies at the Alabama School of Fine Arts and received praise from reviewers worldwide.[77][78]

- Fourteen76[79] is a local online hub for anything related to the arts of Birmingham and surrounding areas. It features local artists, interviews, journalism coverage of the arts and social events, as well as a calendar of local art and music related events.

Birmingham CrossPlex/Fair Park Arena on the west side of town hosts sporting events, local concerts and community programs.- Workplay,[80] located in the Southside community, is a multi-purpose facility with offices, audio and film production space, a lounge, and a theater and concert stage for visiting artists and film screenings.

- The Sidewalk Moving Picture Festival, a celebration of new independent cinema in downtown Birmingham, was named one of Time magazines "Film Festivals for the Rest of Us" in their June 5, 2006, issue. Starting in 2006, the Sidewalk Film Festival became host to the SHOUT Film Festival, Alabama's first and only LGBTQ film festival.

- Wright Center Concert Hall, a 2,500-seat facility at Samford University, is home to the Birmingham Ballet.

Birmingham's nightlife is primarily clustered around the Five Points South, Lakeview, and Avondale districts. In addition, a $55-million "Uptown" entertainment district has recently opened adjacent to the BJCC featuring a number of restaurants and a Westin hotel.

The Cultural Alliance of Greater Birmingham[81] maintains Birmingham365.org,[82] "a one-stop source for finding out what's going on where around" Birmingham.

Museums

Birmingham is home to several museums. The largest is the Birmingham Museum of Art, which is also the largest municipal art museum in the Southeast. The area's history museums include the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which houses a detailed and emotionally charged narrative exhibit putting Birmingham's history into the context of the Civil Rights Movement. It is located on Kelly Ingram Park adjacent to the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Other history museums include the Southern Museum of Flight, Bessemer Hall of History[83]Sloss Furnaces National Historic Landmark, Alabama Museum of Health Sciences, and Arlington Home.

The Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame is housed in the historic Carver Theatre and offers exhibits about the numerous notable jazz musicians from the state of Alabama.

The McWane Science Center is a regional science museum with hands-on science exhibits, temporary exhibitions, and an IMAX dome theater. The center also houses a major collection of fossil specimens for use by researchers. Other unique museums include the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum, which contains the largest collection of motorcycles in the world; the Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama at Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park, near McCalla; and the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

Festivals

Sloss Furnaces

Birmingham is home to numerous cultural festivals showcasing music, films, and regional heritage. The Sidewalk Moving Picture Festival brings filmmakers from all over the world to Birmingham to have their films viewed and judged. This festival usually is scheduled in late August at eight venues around downtown. Screenings are concentrated at the Alabama Theatre. The Sloss Furnaces has an annual Halloween haunted attraction called "Sloss Fright Furnace". During the summer, Sloss Furnaces hosts an annual music and arts festival known as Sloss Music and Arts Festival, or Sloss Fest. Since it began in 2015, the festival has attracted hundreds of national headliners as well as local bands. In its first year, Sloss Fest had approximately 25,000 attendees over its two-day span.[84]

Another musical festival is the Taste of 4th Avenue Jazz Festival, presented at the end of August each year, concurrent with the Sidewalk Moving Picture Festival. This all-day festival features national and local jazz acts. In 2007, the festival drew an estimated 6,000 people. The Birmingham Folk Festival is an annual event held since 2006. It moved to Avondale Park in 2008. In 2009 the festival featured nine local bands and three touring "headliner bands".[85]

Joe Minter's African Village in America is a half-acre visionary art environment near downtown Birmingham.

The Southern Heritage Festival began in the 1960s as a music, arts, and entertainment festival for the African-American community to attract mostly younger demographics. Do Dah Day is an annual pet parade held around the end of May. The Schaeffer Eye Center Crawfish Boil, an annual music festival event held in May to benefit local charities, always includes an all-star cast of talent. It typically draws more than 30,000 spectators for the annual two-day event. The annual Greek Festival, a celebration of Greek heritage, culture, and especially cuisine, is a charity fundraiser hosted by the Greek Orthodox Holy Trinity - Holy Cross Cathedral. The Greek Festival draws 20,000 patrons annually.[86] The Lebanese Food Festival is held at St. Elias Maronite Church. Central Alabama Pride puts on LGBT events each year, including a festival and parade. Magic City Brewfest is an annual festival benefiting local grassroots organization, Free the Hops, and focusing on craft beer. Alabama Bound is an annual book and author fair that celebrates Alabama authors and publishers. Hosted by the Birmingham Public Library, it is an occasion where fans may meet their favorite authors, buy their books, and hear them read from and talk about their work. Book signings follow each presentation.

Other attractions

The Vulcan statue on top of Red Mountain in Vulcan Park

The Vulcan statue is a cast-iron representation of the Roman god of fire, iron and blacksmiths that is the symbol of Birmingham. The statue, cast for the 1904 St. Louis Exposition and erected at Vulcan Park in 1938, stands high above the city looking down from a tower at the top of Red Mountain. Open to visitors, the tower offers views of the city below.

The Birmingham Zoo is a large regional zoo with more than 700 animals and a recently opened interactive children's zoo.

Birmingham Botanical Gardens is a 67-acre (270,000-square-metre) park displaying a wide variety of plants in interpretive gardens, including formal rose gardens, tropical greenhouses, and a large Japanese garden. The facility also includes a white-tablecloth restaurant, meeting rooms, and an extensive reference library. It is complemented by Hoover's 30-acre (120,000 m2) Aldridge Botanical Gardens, an ambitious project open since 2002. Aldridge offers a place to stroll, but is to add unique displays in coming years.

Alabama Splash Adventure (formerly VisionLand and Alabama Adventure) in Bessemer serves as the Birmingham area's water and theme park, featuring numerous slides and water-themed attractions.

Kelly Ingram Park is the site of notable civil rights protests and adjacent to historic 16th Street Baptist Church. Railroad Park opened in 2010 in downtown Birmingham's Railroad Reservation District. Oak Mountain State Park is about 10 miles (16 km) south of Birmingham. Red Mountain is one of the southernmost wrinkles in the Appalachian chain, and a scenic drive to the top provides views reminiscent of the Great Smoky Mountains further north. To the west of the city is located Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park, a 1,500-acre (6.1 km2) Civil War site which includes the well-preserved ruins of the Tannehill Iron Furnaces and the John Wesley Hall Grist Mill.

The Summit is an upscale lifestyle center with many stores and restaurants. It is located in Southeast Birmingham off U.S. Highway 280, parallel to Interstate 459.

Cultural references

The folk song "Down in the Valley", also known as "Birmingham Jail", contains the lines, "Write me a letter, send it by mail; Send it in care of the Birmingham jail."

The song "Sweet Home Alabama" by Lynyrd Skynyrd contains the line "in Birmingham they love the governor".

The song "Black Betty" performed by Lead Belly and Ram Jam, among others, contains the line "She's from Birmingham (bam-ba-lam) Way down in Alabam' (bam-ba-lam)".

Randy Newman wrote a song titled "Birmingham" about a man living in the city. It was released as a track on his 1974 album Good Old Boys.

Birmingham is mentioned in "Playboy Mommy" by American singer-songwriter Tori Amos and in "Run, Baby, Run" by American singer-songwriter Sheryl Crow.

The country band Blackhawk recorded the song "Postmarked Birmingham".[87]

Tracy Lawrence and Ken Mellons each recorded the country song "Paint Me a Birmingham".

The best known song of the husband and wife band Shovels & Rope is their original tune, "Birmingham".

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|

Birmingham Barons | Southern League baseball | Regions Field and Rickwood Field (partime) | 1885 |

Birmingham Legion FC | United Soccer League | 2019 | |

Birmingham Iron | Alliance of American Football | Legion Field | 2019 |

Birmingham has no major professional sport franchises. The Birmingham area is home to the Birmingham Barons, the AA minor league affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, which plays at Regions Field in the Southside adjacent to Railroad Park. The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB Blazers) has a popular basketball program and football program,[88] and Samford University, located in Homewood, has basketball and football teams. The Hoover Metropolitan Stadium in the suburb of Hoover is home to the Southeastern Conference Baseball Tournament which drew more than 108,000 spectators in 2006. There is also an amateur soccer association, known as La Liga, and the Birmingham area hosts the Alabama Alliance basketball teams.

Birmingham was home to the Black Barons, a very successful Negro League baseball team. The Black Barons played home games at Rickwood Field, which is still standing in the Rising-West Princeton neighborhood, and is verified as being the oldest baseball field in America. Scenes from the movies Cobb (1994), Soul of the Game (1995) and 42 (2012) were filmed at Rickwood.

The city has had several pro football franchises. The former pro football team in Birmingham, the Alabama Outlawz of the X-League Indoor Football, folded in 2015. Other teams included the two-time champion WFL franchise the Birmingham Americans/Birmingham Vulcans, before the league folded. The city hosted a USFL franchise, the Birmingham Stallions, but once again the league folded. A WLAF franchise, the Birmingham Fire, was renamed the Rhein Fire when the WLAF was renamed NFL Europa, but the league folded altogether in 2007. A CFL franchise, the Birmingham Barracudas, played one season and then folded as the league ended its American franchise experiment. An XFL franchise, the Birmingham Thunderbolts, were another instance where the league folded. In 2018, the Alliance of American Football introduced the Birmingham Iron, which will play in 2019.[89]

Birmingham's Legion Field has hosted several college football postseason bowl games, including the Dixie Bowl (1948–49), the Hall of Fame Classic (1977–85), the All-American Bowl (1986–90), the SEC Championship Game (1992–93), the SWAC Championship Game (1999–2012), the Magic City Classic (1946–present) and, currently, the Birmingham Bowl (formerly the BBVA Compass Bowl, 2006–present). The Southeastern Conference, Southwestern Athletic Conference, and Gulf South Conference are headquartered in Birmingham.

In 1996, Legion Field hosted early rounds of Olympic soccer where it drew record crowds. The field has also hosted men's and women's World Cup qualifiers and friendlies. A switch from natural grass to an artificial surface has left the stadium's role as a soccer venue in doubt.

Motorsports are very popular in the Birmingham area and across the state, and the area is home to numerous annual motorsport races. The Aaron's 499 & AMP Energy 500 are NASCAR Sprint Cup races that occur in April and October at the Talladega Superspeedway 50 miles (80 km) east of Birmingham. The Indy Grand Prix of Alabama shares the Barber Motorsports Park road course with Superbike and sports car GrandAm races.[90]

The PGA Champions Tour has had a regular stop in the Birmingham area since 1992, with the founding of the Bruno's Memorial Classic, later renamed the Regions Charity Classic. In 2011 the tournament was replaced by The Tradition, one of the Champions Tour's five "major" tour events.

Birmingham has been selected to host the World Games in 2021. It will be the first time that an American city has hosted the event since the inaugural World Games were held in Santa Clara, California, in 1981.[91]

Birmingham is the home of a professional ice hockey team, the Birmingham Bulls of the Southern Professional Hockey League. They play at the Civic Center in nearby Pelham. The Birmingham Bulls was also the name of a team that played in the World Hockey Association from 1976 to 1979 and the Central Hockey League from 1979 to 1981. The WHA Bulls played their home games at the Birmingham Jefferson Convention Center. In 1992, another Birmingham hockey franchise was founded that used the Bulls name, the Birmingham Bulls of the East Coast Hockey League. This franchise was later sold to Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Recreational fishing is popular in the Birmingham area. Recently,[when?] Birmingham was named "Bass Capital of the World" by ESPN and Bassmaster magazine. Over the last several years,[which?] Birmingham has been home to numerous major fishing tournaments, including the Bass Masters Classic.

The U.S. Paralympic Training Facility is located in Birmingham and was a primary filming location for the 2005 documentary film Murderball, about wheelchair rugby players.[92]

The American Sports Medicine Institute (ASMI), located at St. Vincent's Hospital in Birmingham, was founded by Dr. James Andrews in 1987. The institute's mission is to understand, prevent, and treat sports-related injuries. ASMI turned Birmingham into a major medical destination for professional athletes around the country. Dr. Andrews has operated on Bo Jackson, Drew Brees, Roger Clemens, John Smoltz, Charles Barkley, Michael Jordan, and Jack Nicklaus, to name a few. His orthopedics practice is frequently mentioned in books and articles.[93][94]

Birmingham will be home to a USL team called Birmingham Legion FC starting in 2019 and and a NBA G-League team in 2022.

Government

| District | Representative | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LaShunda Scales | |

| 2 | Hunter Williams | |

| 3 | Valerie A. Abbott | President |

| 4 | William Parker | |

| 5 | Darrell O'Quinn | |

| 6 | Sheila Tyson | |

| 7 | James E. Roberson, Jr. | President Pro-Tem |

| 8 | Steven Hoyt | |

| 9 | John R. Hilliard |

Birmingham has a strong-mayor variant mayor–council form of government, led by a mayor and a nine-member city council. The current system replaced the previous city commission government in 1962 (primarily as a way to remove Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor from power).[96]

By Alabama law, an issue before a city council must be approved by a two-thirds majority vote.[97] Executive powers are held entirely by the mayor's office. Birmingham's current mayor is Randall Woodfin.

In 1974 Birmingham established a structured network of neighborhood associations and community advisory committees to insure public participation in governmental issues that affect neighborhoods. Neighborhood associations are routinely consulted on matters related to zoning changes, liquor licenses, economic development, policing and other city services. Neighborhoods are also granted discretionary funds from the city's budget to use for capital improvements. Each neighborhood's officers meet with their peers to form Community Advisory Committees, which are granted broader powers over city departments. The presidents of these committees, in turn, form the Citizens' Advisory Board, which meets regularly with the mayor, council, and department heads. Birmingham is divided into a total of 23 communities, and again into a total of 99 individual neighborhoods with individual neighborhood associations.[98]

State and federal representation

The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Birmingham. The main post office is located at 351 24th Street North in downtown Birmingham.[99] Birmingham is also the home of the Social Security Administration's Southeastern Program Service Center. This center is one of only seven in the United States that process Social Security entitlement claims and payments. In addition, Birmingham is the home of a branch bank of the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank.

Political controversy

Birmingham's recent political history has gained national attention. During his term as mayor, Larry Langford was arrested on charges of bribery. Langford was convicted in 2010 of accepting bribes in exchange for steering $7.1 million in county revenue to a prominent investment banker. The bribes included $230,000 cash, clothes, and jewelry. Langford was sentenced to 15 years in prison and fined $360,000 by a federal judge. The banker, Bill Blount, and a lobbyist, Al la Pierre, pled guilty and were sentenced to brief prison sentences.[100][101]

Former mayor William A. Bell has also been the subject of national scrutiny. In 2015, the mayor got into a physical altercation with city councilman Marcus Lundy. The fight sent both men to the hospital.[102][103]

Education

Woodlawn High School, a magnet school

The city is served by the Birmingham City Schools system. It is run by the Birmingham Board of Education with a current active enrollment of 30,500 in 62 schools: seven high schools, 13 middle schools, 33 elementary schools, and nine kindergarten-eighth-grade primary schools.

Birmingham Public Library administers 21 branches throughout the city and is part of a wider system including another 19 suburban branches in Jefferson County, serving the entire community to provide education and entertainment for all ages.[104]

The greater-Birmingham metropolitan area is the home of numerous independent school systems, because there has been a great deal of fragmentation of educational systems in Alabama and especially Jefferson County. Some of the school systems only have three to five schools. The metropolitan area's three largest school systems are the Jefferson County School System, Birmingham City Schools, and the Shelby County School System. However, there are many smaller school systems.

The Birmingham area is reputed to be the home of some of Alabama's best high schools, colleges and universities. In 2005, the Jefferson County International Baccalaureate School in Irondale, an eastern suburb of Birmingham, was rated as the No. 1 high school in America by Newsweek. The school remains among the nation's top five high schools. Mountain Brook High School placed 250th on the list. Other area schools that have been rated among America's best in various publications include Homewood High School, Vestavia Hills High School, and the Alabama School of Fine Arts located downtown. The metro area also has three highly regarded private college-preparatory schools: Saint Rose Academy, located in Birmingham proper; the Altamont School, also located in Birmingham proper; and Indian Springs School in north Shelby County near Pelham.

Noteworthy institutions of higher education in greater Birmingham include the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Samford University (including the Cumberland School of Law), Birmingham School of Law, Miles College, the independent Miles Law School, Jefferson State Community College, Birmingham-Southern College, University of Montevallo (in Shelby County), Lawson State Community College, and Virginia College in Birmingham, the largest career college based in Birmingham.

Media

Birmingham is served by one major newspaper, The Birmingham News (circulation 150,346), which changed from daily to thrice-weekly publication on October 1, 2012. The Birmingham News' Wednesday edition features six subregional sections named East, Hoover, North, Shelby, South, and West that cover news stories from those areas. The newspaper has been awarded two Pulitzer Prizes, in 1991 and 2007. The Birmingham Post-Herald, the city's second daily, published its last issue in 2006. Other local publications include The North Jefferson News, The Leeds News, The Trussville Tribune (Trussville, Clay and Pinson), The Western Star (Bessemer) and The Western Tribune (Bessemer).

Weld for Birmingham, Birmingham Weekly and Birmingham Free Press[105] are Birmingham's free alternative publications. The Birmingham Times, a historic African-American newspaper, also is published weekly. Birmingham is served by the city magazine, Birmingham magazine, owned by The Birmingham News.

Birmingham is part of the Birmingham/Anniston/Tuscaloosa television market. The major television affiliates, most of which have their transmitters and studios located on Red Mountain in Birmingham, are WBRC 6 (Fox), WBIQ 10 (PBS), WVTM 13 (NBC), WTTO 21 (CW), WIAT 42 (CBS), WPXH 44 (ION), WBMA-LD 58/68.2 (ABC) and WABM 68 (MyNetworkTV).

NOAA weather radio station KIH54 broadcasts weather and hazard information for the Birmingham Metropolitan Area.

Major broadcasting companies who own stations in the Birmingham market include IHeartMedia, SummitMedia, Cumulus Media, and Crawford Broadcasting. The Rick and Bubba Show, which is syndicated to over 25 stations primarily in the Southeast, originates from Birmingham's WZZK-FM. The Paul Finebaum sports-talk show, also syndicated and carried nationwide on Sirius digital radio, originated from WJOX.

Birmingham is home to EWTN (Eternal Word Television Network), the world's largest Catholic media outlet and largest religious network of any kind, broadcasting to about 150 million homes worldwide as of 2009[update].[106]

Urban planning

View of Birmingham from Railroad Park

Before the first structure was built in Birmingham, the plan of the city was laid out over a total of 1,160 acres (4.7 km2) by the directors of the Elyton Land Co. The streets were numbered from west to east, leaving 20th Street to form the central spine of downtown, anchored on the north by Capital Park and stretching into the slopes of Red Mountain to the south. A "railroad reservation" was granted through the center of the city, running east to west and zoned solely for industrial uses. As the city grew, bridges and underpasses separated the streets from the railroad bed, lending this central reservation some of the impact of a river (without the pleasant associations of a waterfront). From the start, Birmingham's streets and avenues were unusually wide at 80 to 100 feet (24 to 30 m), purportedly to help evacuate unhealthy smoke.

In the early 20th century professional planners helped lay out many of the new industrial settlements and company towns in the Birmingham District, including Corey (now Fairfield), which was developed for the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (subsequently purchased by U.S. Steel). At the same time, a movement to consolidate several neighboring cities gained momentum. Although local referendums indicated mixed feelings about annexation, the Alabama legislature enacted an expansion of Birmingham's corporate limits that became effective on January 1, 1910.

The Robert Jemison Company developed many residential neighborhoods to the south and west of Birmingham which are still renowned for their aesthetic quality.

A 1924 plan for a system of parks, commissioned from the Olmsted Brothers, is seeing renewed interest with several significant new parks and greenways under development. Birmingham officials have approved a City Center Master Plan developed by Urban Design Associates of Pittsburgh, which advocates strongly for more residential development in the downtown area. The plan also called for a major park over several blocks of the central railroad reservation: Railroad Park, which opened in 2010. Along with Ruffner Mountain Park and Red Mountain Park, Birmingham ranks first in the United States for public green space per resident.[citation needed]

Infrastructure

Transportation

The city of Birmingham has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 15.8 percent of Birmingham households lacked a car, and decreased to 12.3 percent in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Birmingham averaged 1.48 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[107]

Highways

Interstate 59 (co-signed with Interstate 20) approaching Interstate 65 in downtown Birmingham

I-20

I-20

I-22

I-22

I-59

I-59

I-65

I-65

I-222 (proposed connector between I-22 and I-422; direct interchange cannot be built due to topography)

I-222 (proposed connector between I-22 and I-422; direct interchange cannot be built due to topography)

I-422 (proposed Northern Bypass)

I-422 (proposed Northern Bypass)

I-459 (Southern Bypass)

I-459 (Southern Bypass)

The city is served by four Interstate Highways: Interstate 20, Interstate 65, Interstate 59, and Interstate 22, as well as a southern bypass expressway Interstate 459, which connects with I-20/59 to the southwest, with I-65 to the south, I-20 to the east, and I-59 to the northeast. Beginning in downtown Birmingham is the Elton B. Stephens Expressway—the "Red Mountain Expressway" to the southeast—which carries U.S. Highway 31 and U.S. Highway 280 to, through, and over Red Mountain. Interstate 22 connects I-65 and Memphis, Tennessee. Construction has begun on the first segment of I-422, a Northern Beltline Highway that will serve the suburbs on the opposite side of Birmingham from I-459.

Public transport

The Birmingham Street Railway in 1903

In the area of metropolitan public transportation, Birmingham is served by the Birmingham-Jefferson County Transit Authority (BJCTA) bus, trolley, and paratransit system, which from 1985 until 2008 was branded the Metro Area Express (MAX). BJCTA also operates a "downtown circulator" service named "D A R T" for Downtown Area Runabout Transit, which consists of two routes in the central business district and one in the UAB area, and also operates hourly Airport Shuttle routes directly from downtown and UAB area hotels to the airport.[108] Bus service to other cities is provided by Greyhound Lines.[109]Megabus offers bus service to Atlanta and Memphis.[110]

Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport, 4 miles (6 km) northeast of downtown, serves more than 3 million passengers every year. With more than 160 flights daily, the airport offers flights to 37 cities provided by United Express, Delta Air Lines/Delta Connection, American Eagle, and Southwest Airlines.

Birmingham is served by three major railroad freight lines: the Norfolk Southern Company, CSX Transportation, and the BNSF Railway, together with smaller regional railroads, the Alabama Warrior Railway and the Birmingham Southern Railroad. Amtrak operates one passenger train, the Crescent, each direction daily.

Utilities

The water for Birmingham and the intermediate urbanized area is served by the Birmingham Water Works Board (BWWB). A public authority that was established in 1951, the BWWB serves all of Jefferson, northern Shelby, and western St. Clair counties. The largest reservoir for BWWB is Lake Purdy, which is located on the Jefferson and Shelby County line, but has several other reservoirs including Bayview Lake in western Jefferson County. There are plans to pipeline water from Inland Lake in Blount County and Lake Logan Martin, but those plans are on hold indefinitely.

Jefferson County Environmental Services serves the Birmingham metro area with sanitary sewer service. Sewer rates have increased in recent years[111] after citizens concerned with pollution in area waterways filed a lawsuit that resulted in a federal consent decree to repair an aging sewer system. Because the estimated cost of the consent decree was approximately three times more than the original estimate, many blame the increased rates on corruption of several Jefferson County officials.[111] The sewer construction and bond-swap agreements continue to be a controversial topic in the area.[111]

Electric power is provided primarily by Alabama Power, a subsidiary of the Southern Company. However, some of the surrounding area such as Bessemer and Cullman are provided power by the TVA. Bessemer also operates its own water and sewer system.[112] Natural gas is provided by Alagasco, although some metro area cities operate their own natural gas services. The local telecommunications are provided by AT&T. Cable television service is provided by Bright House Networks within the cities of Birmingham and Irondale, and Charter Communications in the rest of the metro area.

Notable people

Sister cities

Birmingham's Sister Cities program is overseen by the Birmingham Sister Cities Commission.[113]

|

|

See also

Notes

^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

^ Official records for Birmingham kept April 1895 to December 1929 at the Weather Bureau Office and at Birmingham Int'l since January 1930. For more information, see Threadex.

References

^ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 7, 2018..mw-parser-output cite.citation{font-style:inherit}.mw-parser-output q{quotes:"""""""'""'"}.mw-parser-output code.cs1-code{color:inherit;background:inherit;border:inherit;padding:inherit}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-free a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/65/Lock-green.svg/9px-Lock-green.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-limited a,.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-registration a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d6/Lock-gray-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-gray-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-lock-subscription a{background:url("//upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/Lock-red-alt-2.svg/9px-Lock-red-alt-2.svg.png")no-repeat;background-position:right .1em center}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration{color:#555}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription span,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration span{border-bottom:1px dotted;cursor:help}.mw-parser-output .cs1-hidden-error{display:none;font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-visible-error{font-size:100%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-subscription,.mw-parser-output .cs1-registration,.mw-parser-output .cs1-format{font-size:95%}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-left,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-left{padding-left:0.2em}.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-right,.mw-parser-output .cs1-kern-wl-right{padding-right:0.2em}

^ ab "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Birmingham city, Alabama". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

^ ab "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 24, 2018.

^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Birmingham city, Alabama; Alabama". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

^ Pickett, Albert James; Owen, Thomas McAdory (2003) [1851]. History of Alabama, and Incidentally of Georgia and Mississippi, from the Earliest Period. 1. Montgomery, Ala.: River City Publishing. p. 391. ISBN 978-1880216705. Archived from the original on July 4, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

^ ab Connerly, Charles E. (11 July 2013). "The Most Segregated City in America": City Planning and Civil Rights in Birmingham, 1920–1980. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-3538-6.

^ Lewis, David. "Birmingham Iron and Steel companies". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

^ ab Flynt, Wayne (February 5, 2016). Poor But Proud. University of Alabama Press.

^ Atkins, Leah Rawls (1981). The Valley and the Hills: An Illustrated History of Birmingham & Jefferson County. Windsor Publications. ISBN 978-0-89781-031-9.

^ Cohen, Adam (July 21, 1997). "Back to "Bombingham"". TIME. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

^ Clayborne Carson[permanent dead link] "King Maker", American Heritage, Winter 2010.

^ Gado, Mark (2007). "Bombingham". CrimeLibrary.com/Court TV Online. Archived from the original on August 18, 2007.

^ "The Birmingham Campaign". Civil Rights Movement Veterans.

^ "encyclopediaofalabama.org". encyclopediaofalabama.org. May 12, 2011. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

^ ab "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Birmingham city, Alabama". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

^ "Alabama – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". Census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

^ "Birmingham sees no population growth, suburban cities still increasing, Census shows". U.S. Census Bureau.

^ Dugan, Kelli M. (July 14, 2006). "Big ideas". Birmingham Business Journal. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

^ "Highland Park in Birmingham". American Planning Assoc. website. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

^ "Birmingham wins! City chosen as site for 2021 World Games". Al.com. January 26, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

^ "Birmingham Has a Lot on Its Plates These Days". The New York Times. December 15, 2006.

^ "36 Hours in Birmingham, Ala". The New York Times. April 16, 2009.

^ "Birmingham Restaurant With Fire in Its Belly". The New York Times. August 5, 2016.

^ "Birmingham: With revitalized neighborhoods and a ramped-up food culture, Alabama's largest city boldly returns to the stage and sings to a bigger audience". The Washington Post. March 9, 2017.

^ "Birmingham, Ala., embraces its complex history". Los Angeles Times. April 14, 2013.

^ "Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2016. Retrieved 2015-06-09.CS1 maint: Archived copy as title (link)

^ "How to extort money from City of Homewood: Reader opinion". Al.com. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

^ abcd "Station Name: AL BIRMINGHAM AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

^ "July Daily Averages for Birmingham, AL (35209)". Weather.com. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

^ "February Daily Averages for Birmingham, AL (35209)". weather.com. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2018-08-01.

^ "WMO Climate Normals for BIRMINGHAM/WSFO AL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

^ "WMO Climate Normals for BIRMINGHAM/MUNICIPAL ARPT AL 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

^ "Average Weather for Birmingham, AL – Temperature and Precipitation". The Weather Channel. December 2011. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

^ "Birmingham, Alabama (Look for "earthquake activity")". City-data.com. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

^ "Historic Earthquakes". Earthquake.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

^ "Birmingham city, Alabama: Selected Economic Characteristics: 2007–2011". Census.gov. Retrieved November 13, 2013.

^ "Religious Congregations & Membership Study". Rcms2010.org. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

^ "Most and Least Christian Cities in America (PHOTOS)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

^ "The Association of Religion Data Archives – Maps & Reports". Thearda.com. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

^ "Parish Directory". Diocese of Birmingham Official Website. Catholic Diocese of Birmingham. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

^ "Study: Three Alabama cities ranked among nation's most dangerous - Yellowhammer News". Yellowhammernews.com. February 25, 2014.

^ "The Most Dangerous Cities in America". 247wallst.com.

^ "2012 City Crime Rate Rankings* (continued)" (PDF). Os.cqpress.com. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

^ "2010 Metropolitan Crime Rate Rankings*" (PDF). Os.cqpress.com. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

^ "FBI statistics suggest the need for new crime-fighting strategies and technologies for Birmingham" Archived September 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. The Birmingham News via AL.com, January 10, 2008.

^ "The 11 Most Dangerous Cities" Archived June 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. U.S. News & World Report, February 26, 2011.

^ "Steel Dynamics to Acquire Vulcan Threaded Products to Expand SBQ Finishing Capabilities". Prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

^ Dan Bagwell. "Top of the List: Bham's largest employers" (April 22, 2011). Birmingham Business Journal.

^ "Birmingham, Hoover Career, Salary & Employment Info". Collegedegreereport.com. Retrieved 2017-01-07.